Cluster Evaluation of Health Infrastructure Support for First Nations and Inuit

PDF Version (4.1 Mb, 164 pages)

June 28, 2023

Acknowledgements

We wish to honour the traditional territories of the Indigenous Peoples, upon whose land this evaluation has been carried out.

The Algonquin Anishinaabe; The Mississaugas of the Credit; the Anishnabeg; the Chippewa; the Haudenosaunee; the Wendat Peoples; the Huron-Wendat Peoples; the Métis Nation of Ontario; the Métis Nation of Alberta Region 4; the Nehiyaw; the Denesuliné; the Nakota Sioux; Nakota Isga; the Saulteaux; the Anishinaabe and the Niitsitapi.

This evaluation involved engagements which were carried out from coast to coast. We wish to thank the individuals who shared their knowledge, wisdom, and painful truths with us. We thank them for trusting us with their experiences.

Emotional Trigger Warning

This report discusses culturally unsafe experiences in health care, traumatic experiences and health and wellness topics that may trigger memories of personal experiences or the experiences of friends and family. This report also discusses racism, chronic health conditions, and fatality. While the report's intent is to create knowledge and respond to questions about the achievement of outcomes for Cluster programs, the content may trigger difficult feelings or thoughts. Indigenous peoples who require emotional support can contact the 24-hour KUU-US Crisis Line at 1-800-588-8717 to connect with an Indigenous Crisis Responder.

Table of contents

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Table of Figures

- Table of Tables

- Executive Summary

- Key Findings

- Evaluation Recommendations

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Findings

- 3.1 Relevance

- Evaluation Question: What are the needs that this cluster of health programs for First Nations and Inuit should address? Are the needs still relevant and/or have new needs arisen?

- Evaluation Question: Are the objectives of this cluster of programs (i.e., what the programs are designed to do) aligned to the needs of First Nations and Inuit?

- 3.2 Effectiveness

- Evaluation Question: What aspects of the programs are working well and what aspects need improvement?

- Evaluation Question: To what extent has each of the programs included made progress toward the achievement of their respective expected outcomes?

- Evaluation Question: How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact the delivery of the programs and their ability to support First Nations and Inuit?

- Evaluation Question: How effective/productive are the relationships between partners within each of the programs (e.g., between ISC Headquarters and regional offices, First Nations and Inuit, implementing partners, provincial and municipal governments, etc.) and between programs?

- 3.3 Service Transfer

- 3.4 Efficiency

- 3.1 Relevance

- 4. Conclusions

- 5. Recommendations

- Appendices

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AB

- Alberta

- ACCHOs

- Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organizations

- AFN

- Assembly of First Nations

- ATL

- Atlantic

- BC

- British Columbia

- BCT

- British Columbia Tripartite

- CDC

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CMA

- Census Metropolitan Area

- CPS&QF

- Canadian Patient Safety & Quality Framework

- CS&H

- British Columbia Declaration on Cultural Safety and Humility

- CSPI

- Canadian Patient Safety Institute

- EAC

- Evaluation Advisory Committee

- eHealth

- eHealth Infostructure Program

- EMR

- Electronic Medical Records

- F – O&M

- Facilities – Operations & Maintenance

- FHQTC

- File Hills Qu'Appelle Tribal Council

- FNHA

- First Nations Health Authority

- FNHMA

- First Nations Health Managers Association

- FNIHB

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

- FTE

- Full-Time Equivalent

- GBA Plus

- Gender-Based Analysis Plus

- GCR

- General Condition Rating

- GoC

- Government of Canada

- H&CC

- Home and Community Care

- HFP

- Health Facilities Program

- HHR

- Health Human Resources

- HIV

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HPQM

- Health Planning and Quality Management

- HPQM&SI

- Health Planning, Quality Management and Systems Integration

- HQ

- Headquarters

- HSIF

- Health Services Integration Fund

- HSO

- Health Standards Organization

- HVAC

- Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning

- IELCC

- Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care

- ISC

- Indigenous Services Canada

- ITK

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

- LPN

- Licensed Practical Nurse

- MB

- Manitoba

- MHO

- Ministry of Health and Long-term Care

- MKO

- Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Inc.

- MMIWG2S

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People

- MOU

- Memorandum of Understanding

- NATSIHP

- National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan

- NFR

- New Fiscal Relationship

- NNADAP

- National Native Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program

- NISR

- National Inuit Strategy on Research

- NR

- Northern

- OCAP®

- Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (referring to First Nations Principles of OCAP®)

- ON

- Ontario

- PIP

- Performance Information Profile

- PT

- Provincial and Territorial

- QC

- Quebec

- QIAP

- Quality Improvement and Accreditation Program

- RMT

- Registered Massage Therapist

- RN

- Registered Nurses

- SCO

- Southern Chiefs Organization

- SK

- Saskatchewan

- SME

- Subject Matter Expert

- STI

- Sexually Transmitted Infection

Table of Figures

- Figure 1 - FNHA depicted the First Nations' perspective of health and wellness (FNHA, n.d.)

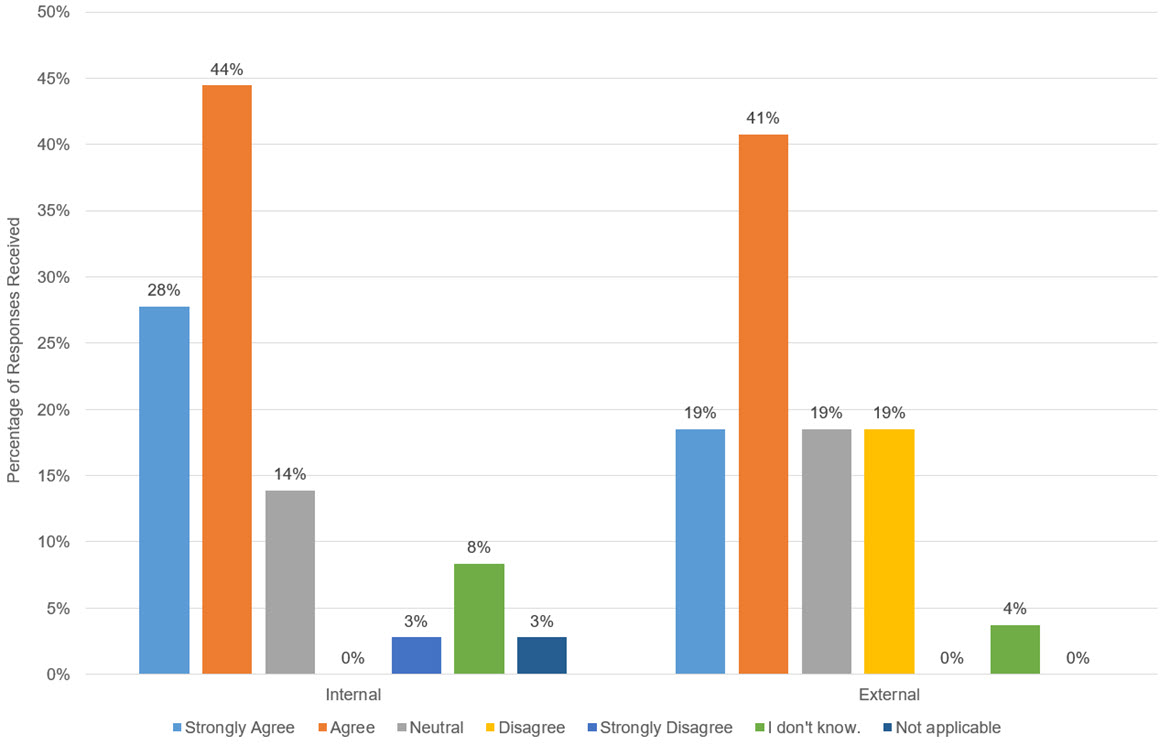

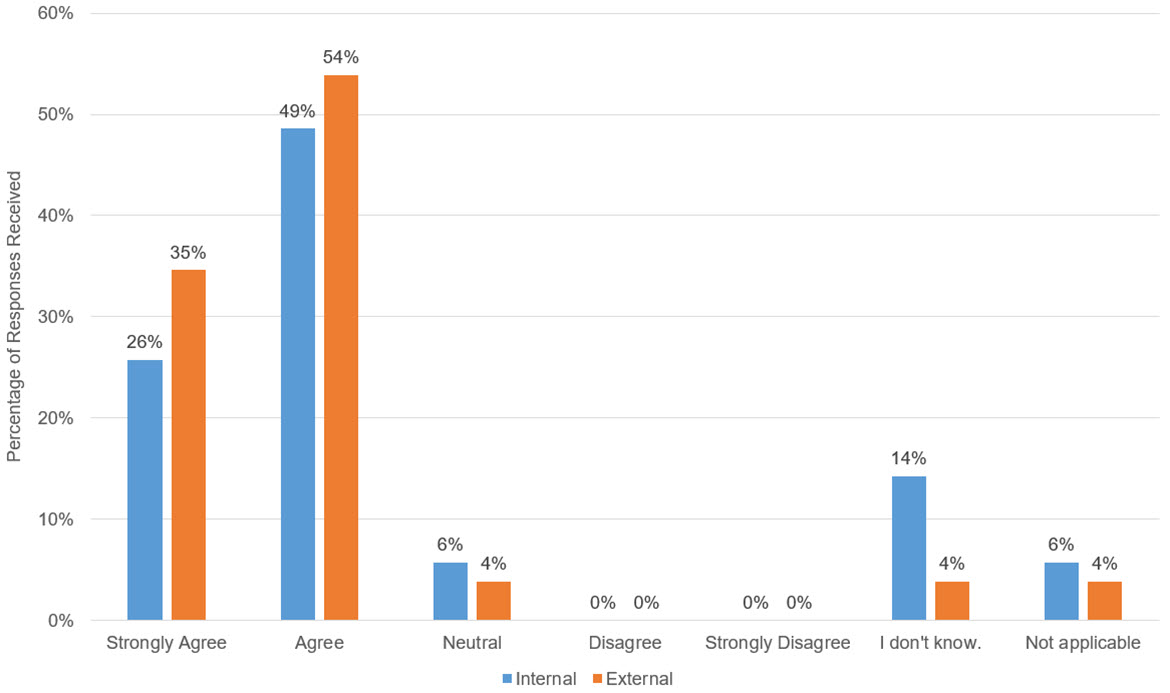

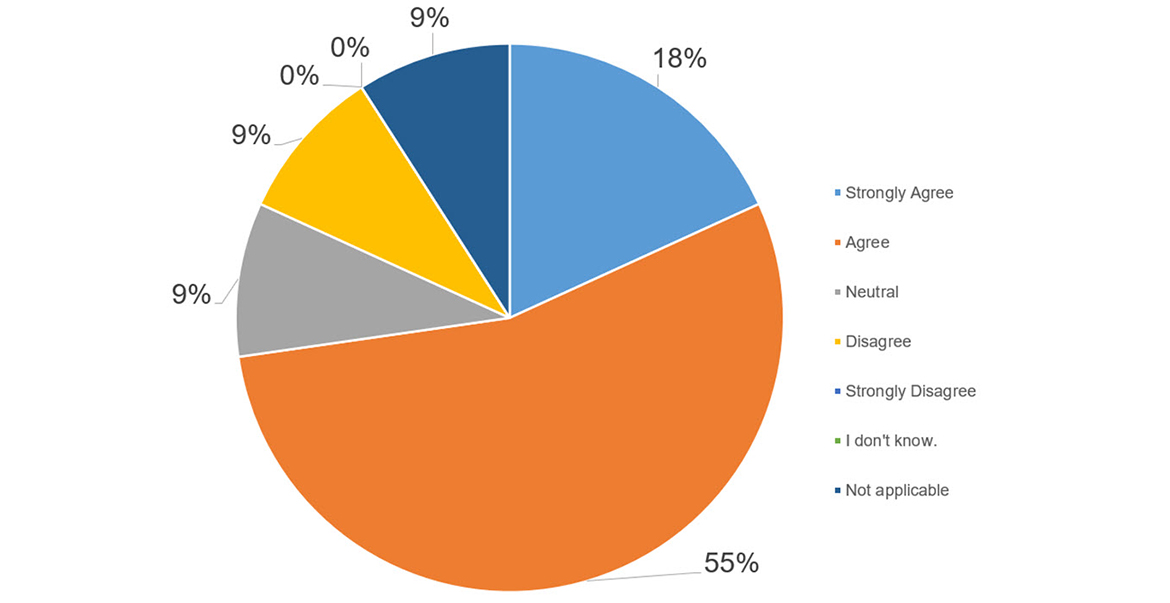

- Figure 2 - The Cluster program(s) respect First Nations and Inuit values and rights, including right to access cultural ceremonies, practices, and supports

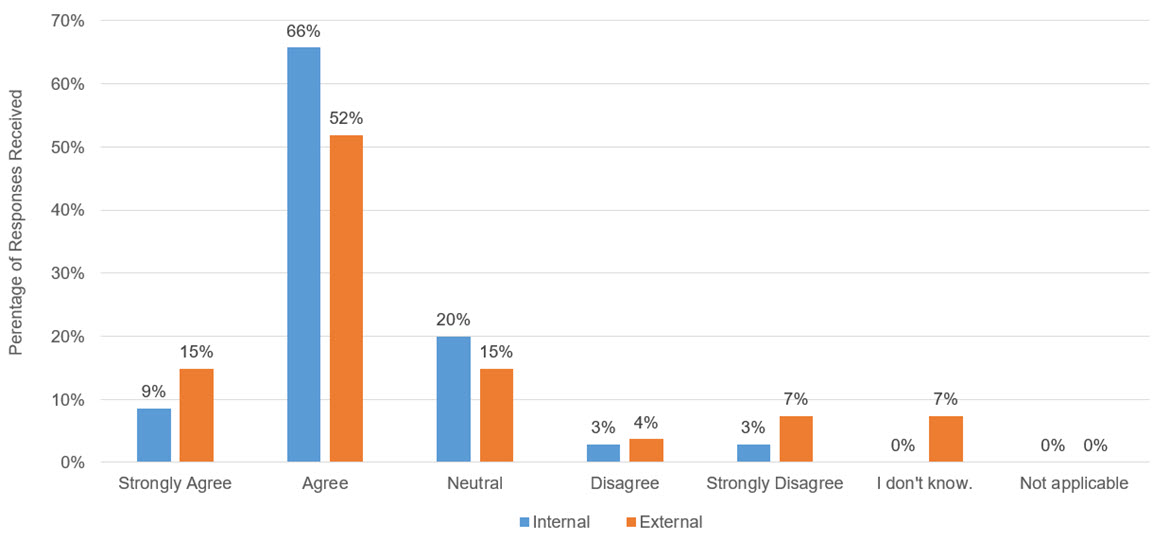

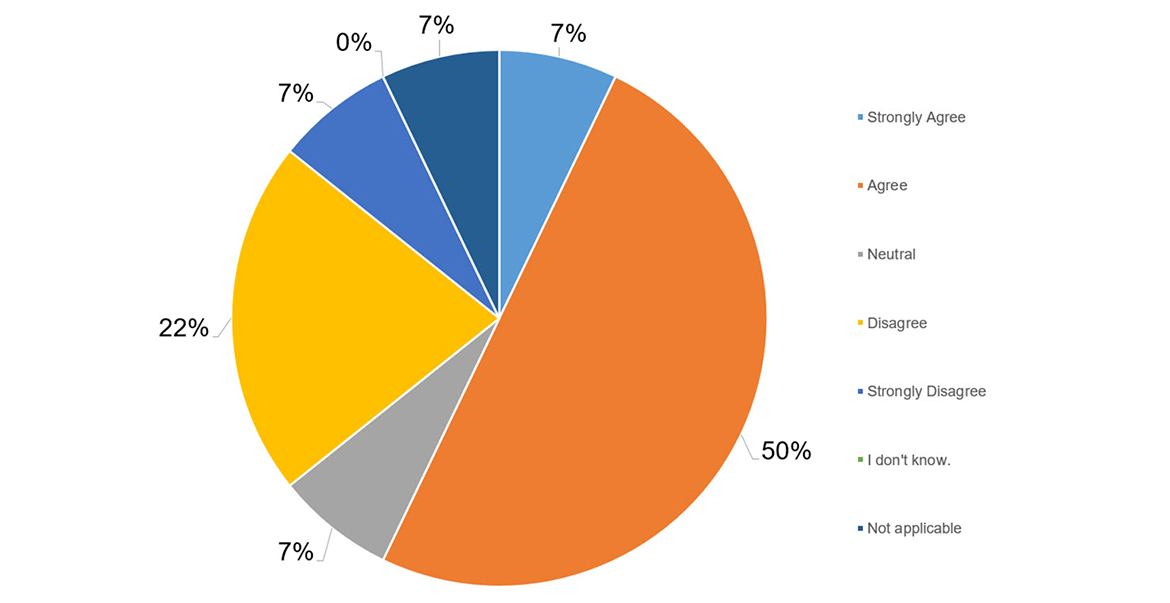

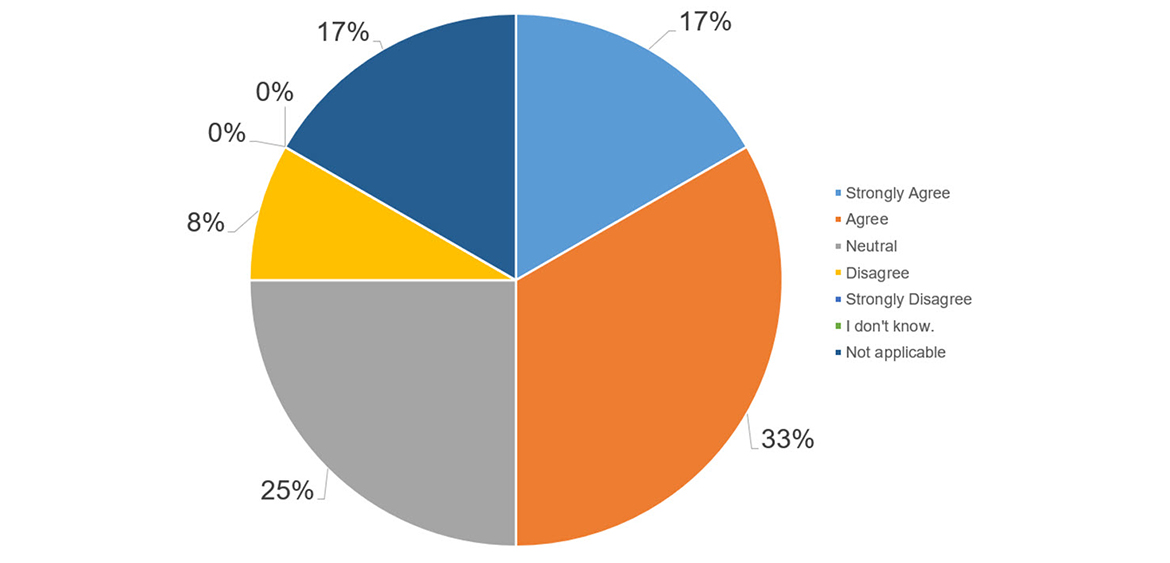

- Figure 3 - There is an established culture of accountability to advance anti-racism and cultural safety and humility in my organization

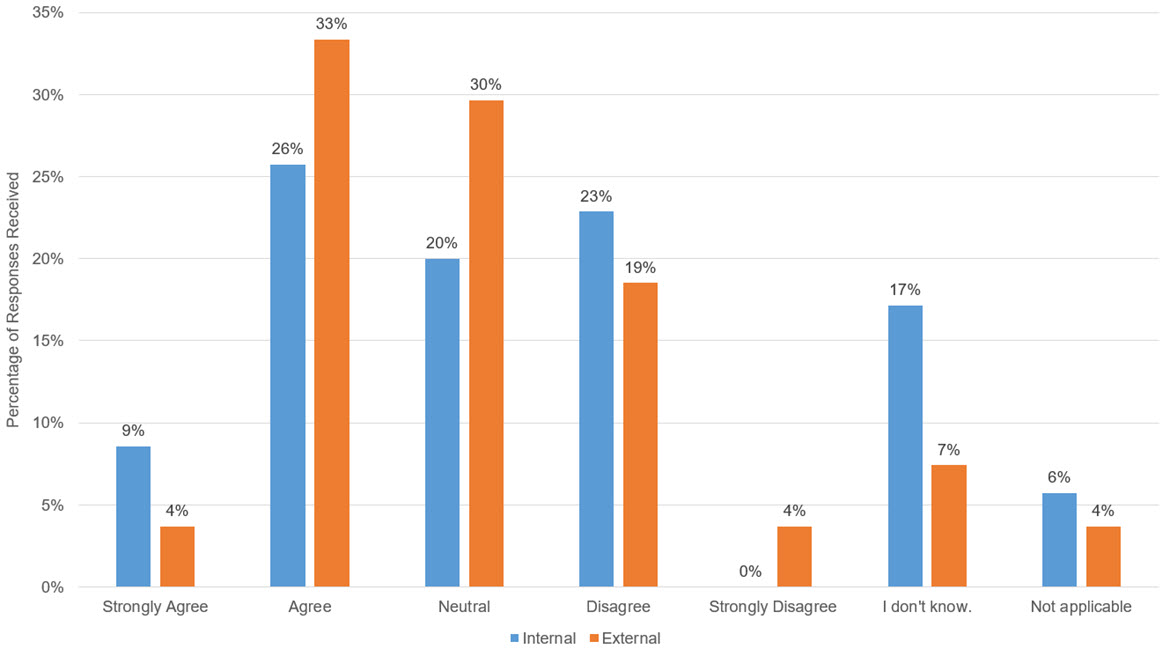

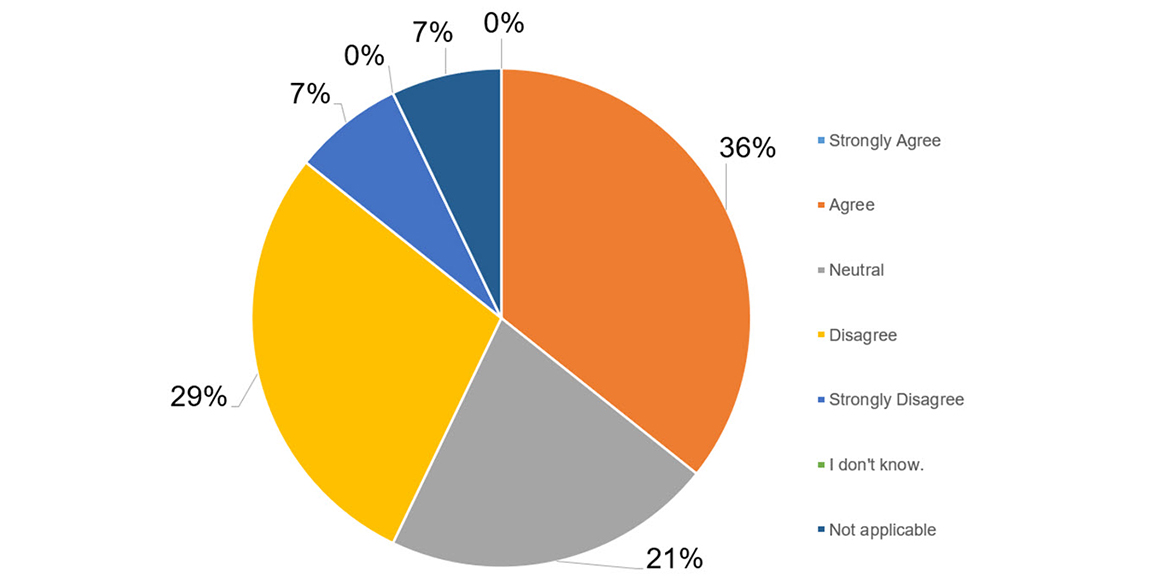

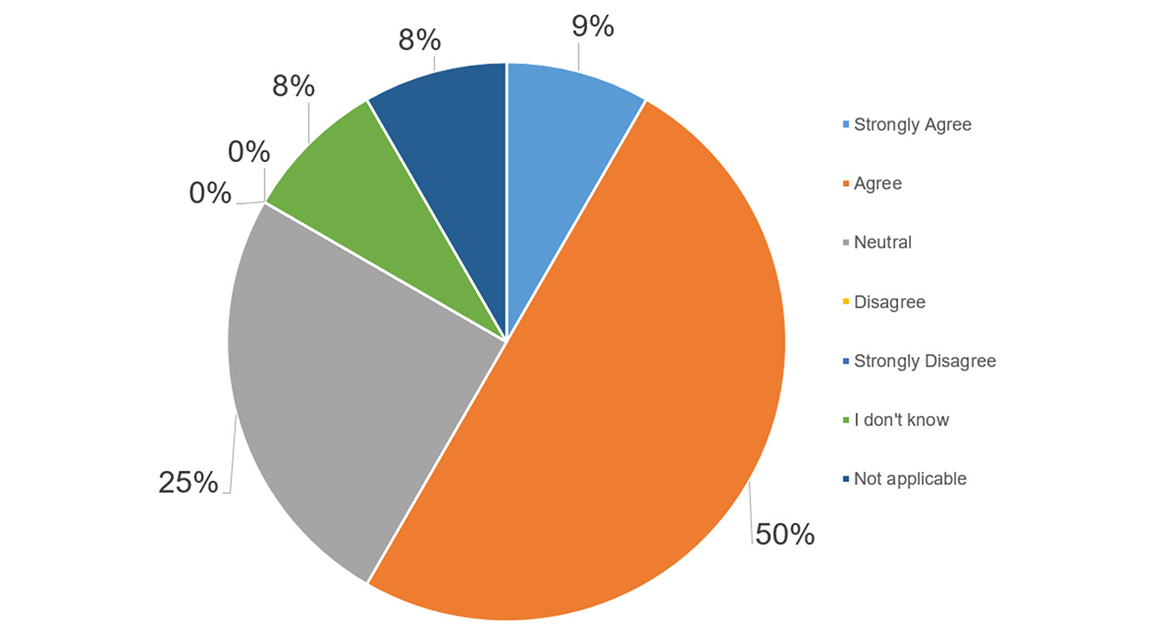

- Figure 4 - The Cluster programs allow for services that are safe and free from preventable harm

- Figure 5 - The Cluster programs could be improved for better patient safety and harm prevention

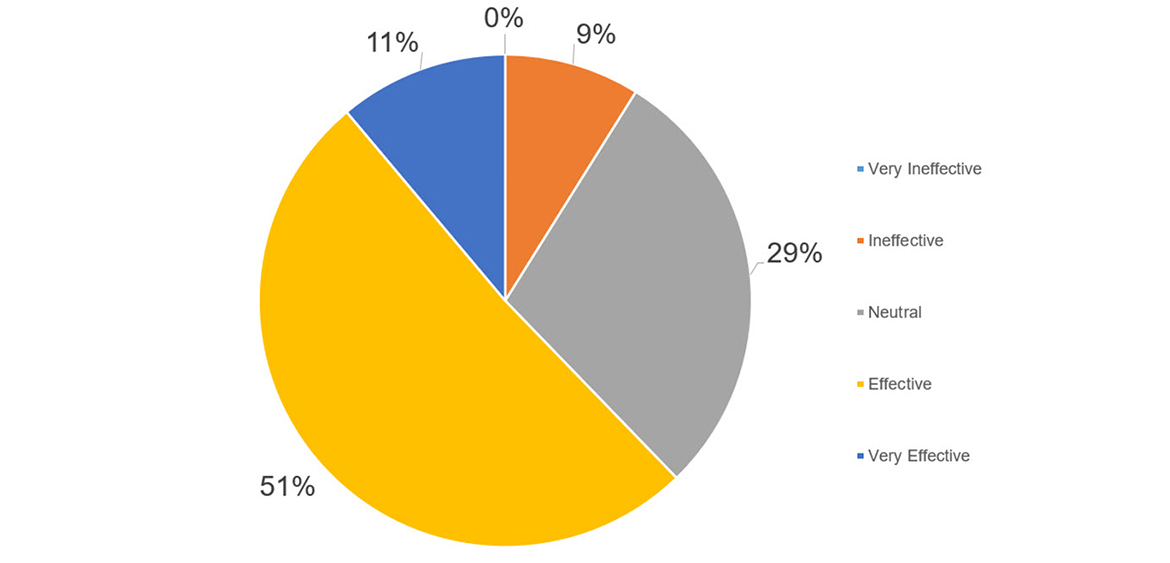

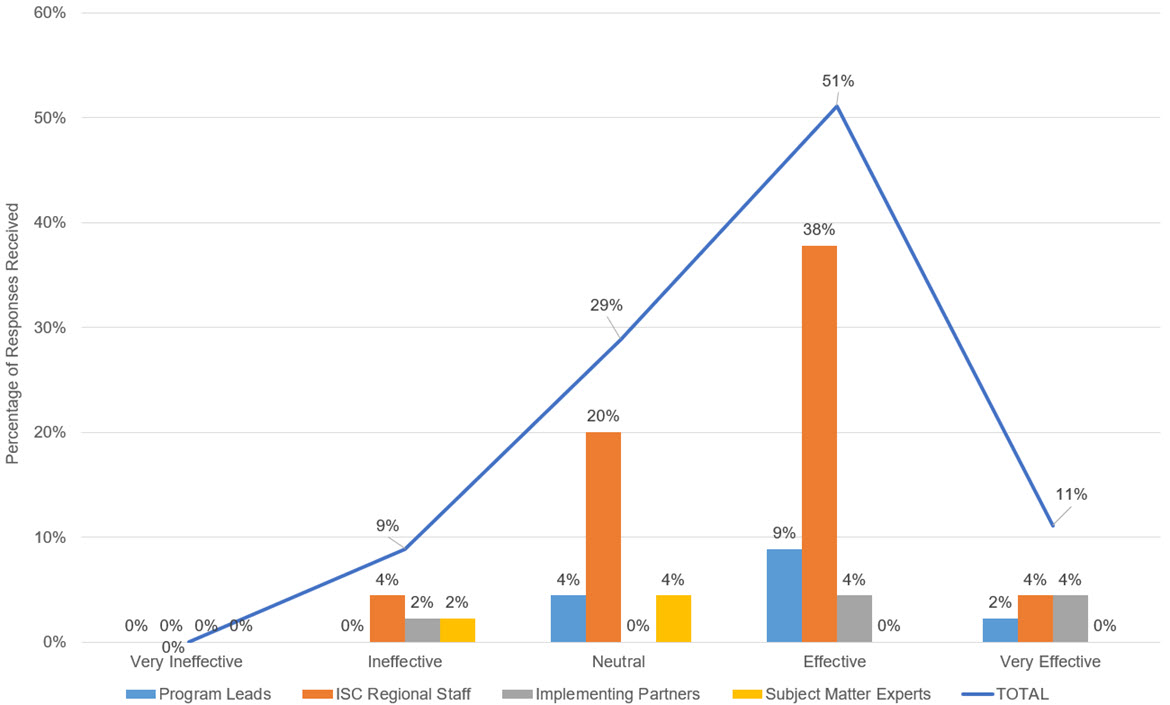

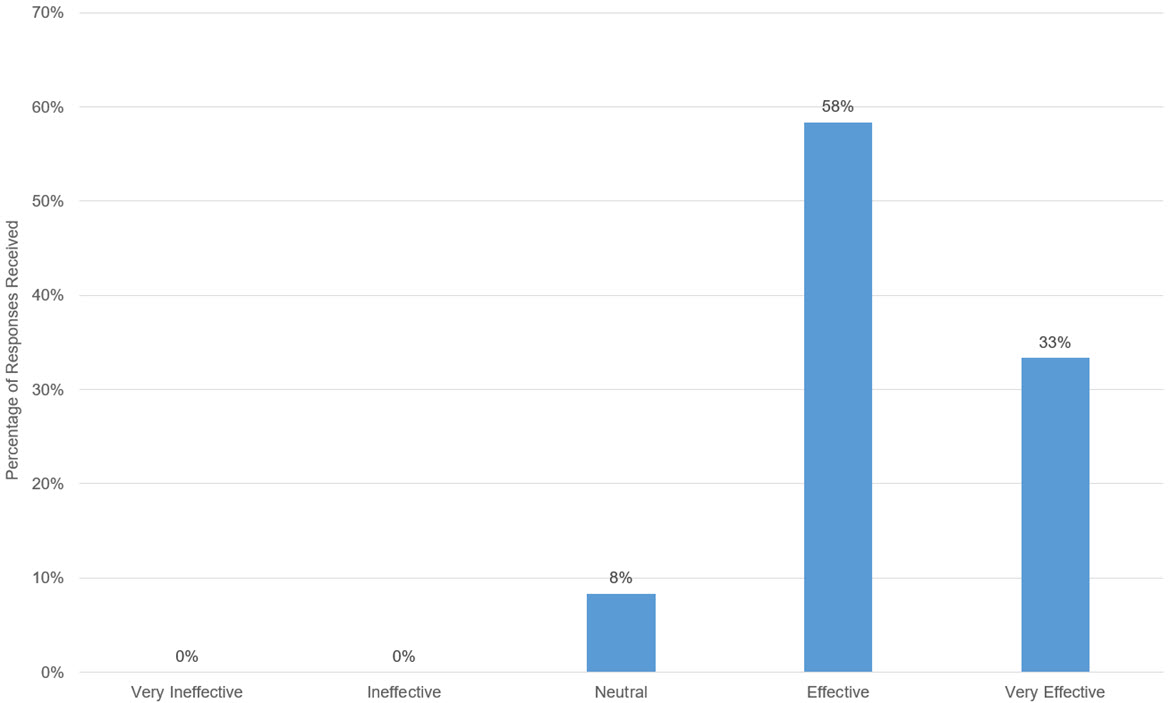

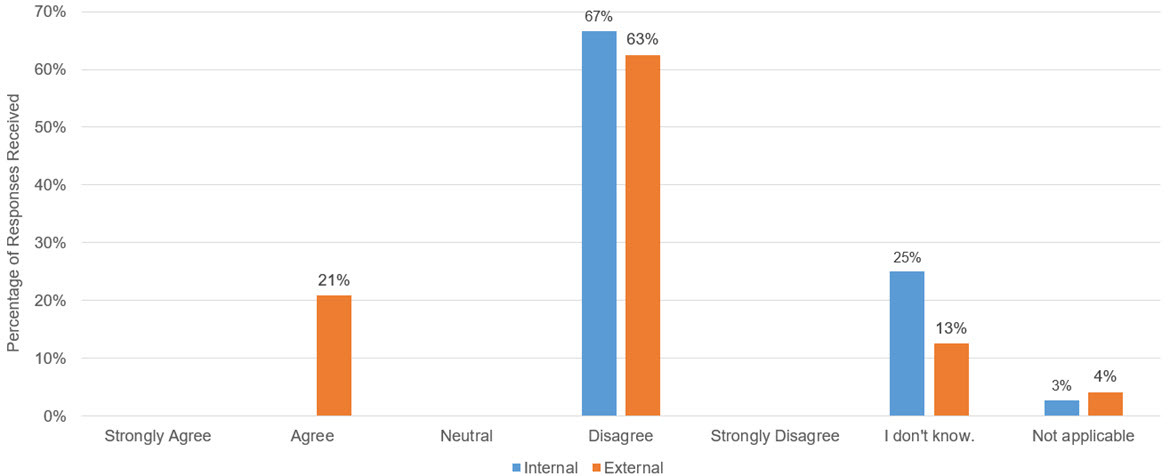

- Figure 6 - Perception of Partners on Overall Effectiveness of Program Delivery

- Figure 7 - First Nation and Inuit Supported by ISC to Develop a Community Health Plan

- Figure 8 - Access to wholistic health services has increased between 2015-2020

- Figure 9 - The quality of care provided is excellent because of HPQM

- Figure 10 - HSIF Projects as of 2022 By Region

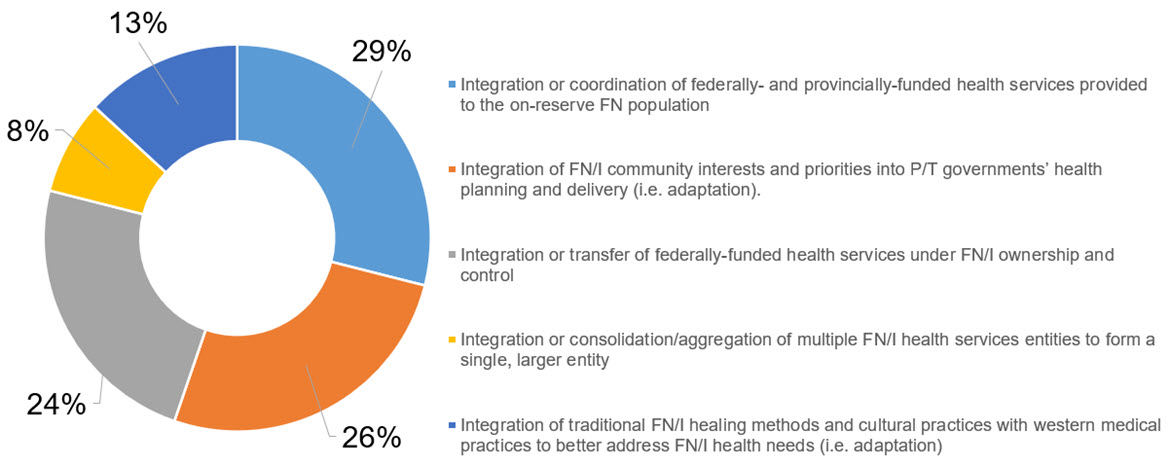

- Figure 11 - Sample of HSIF Projects, Types of Integration Covered by Projects Reported

- Figure 12 - HSIF Sample of Projects Focus Areas

- Figure 13 - Access to wholistic health services has increased between 2015-2020

- Figure 14 - The quality of care is excellent because of HSIF

- Figure 15 - There is a high level of satisfaction of services delivered through HSIF

- Figure 16 - Breakdown of Bursary Recipients by Region

- Figure 17 - Breakdown of Bursary Recipients by Programs of Study

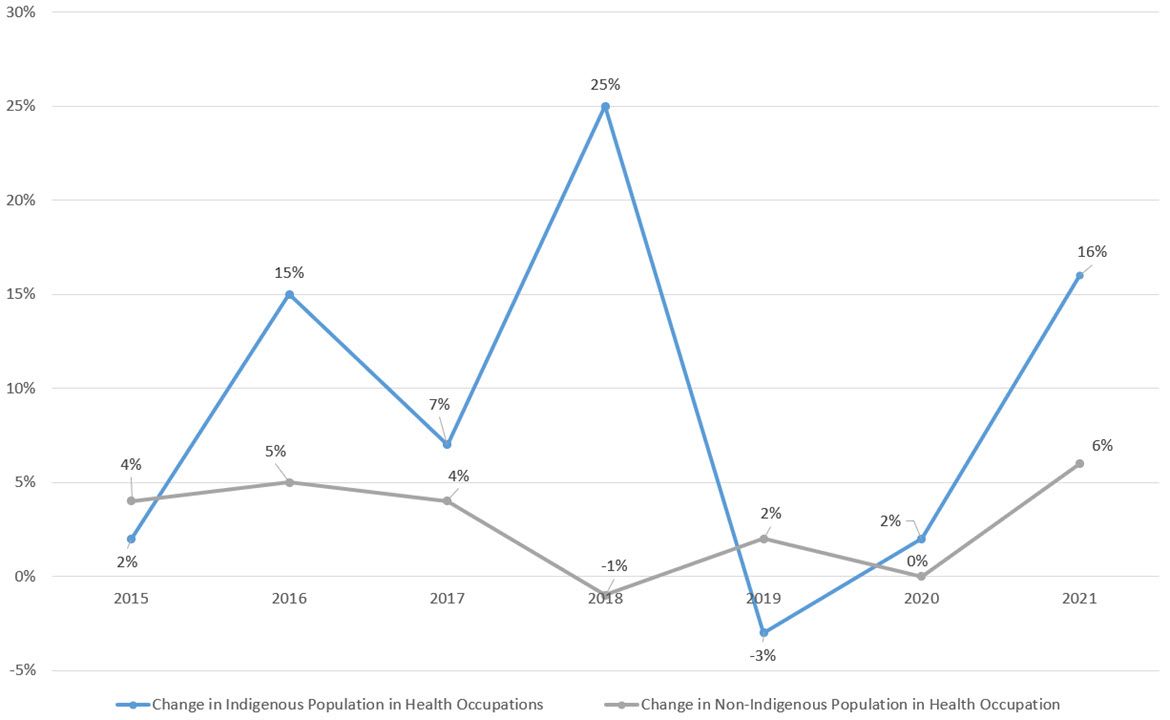

- Figure 18 - Annual Percentage Change in Number of Indigenous peoples and Non-Indigenous People Working in Health Care in Canada

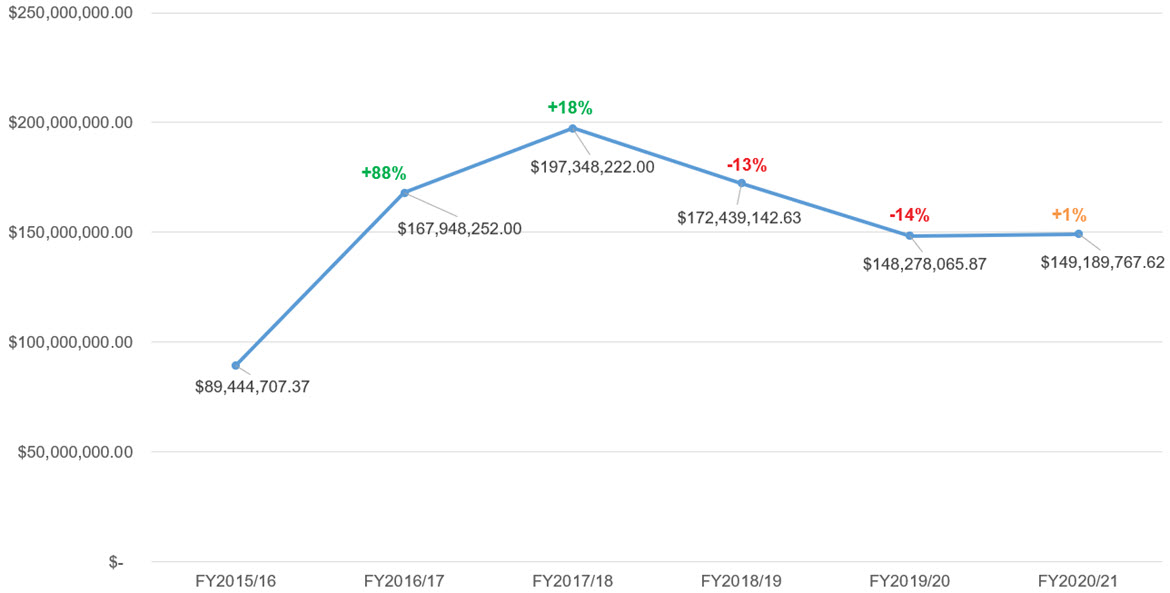

- Figure 19 - HFP Program Expenditures

- Figure 20 - Services Enabled by Accreditation

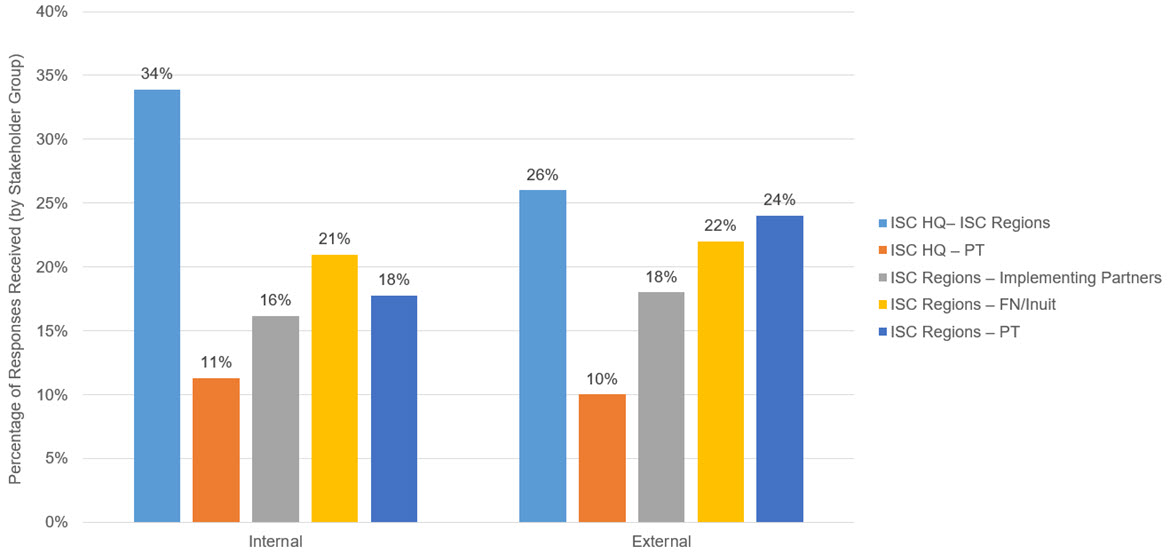

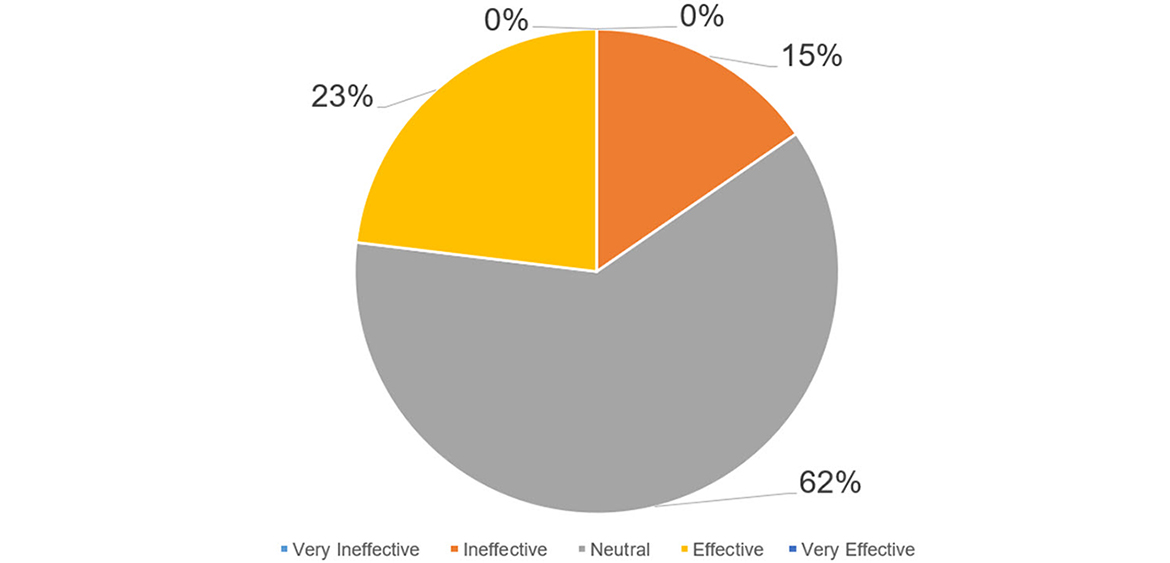

- Figure 21 - Overall Effectiveness of Relationships Between Program Partners

- Figure 22 - Overall Effectiveness of Relationships Between Program Partners

- Figure 23 - Effectiveness of Relationships Between ISC HQ and ISC Regions

- Figure 24 - Effectiveness of Relationships Between ISC Regions and First Nations and Inuit

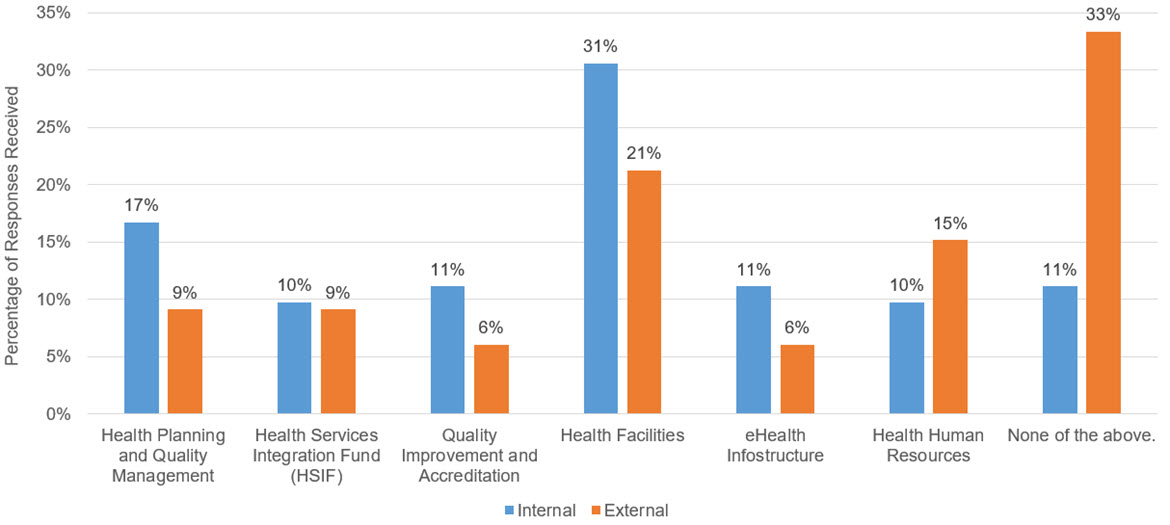

- Figure 25 - Which relationships need to be strengthened to improve the program's function?

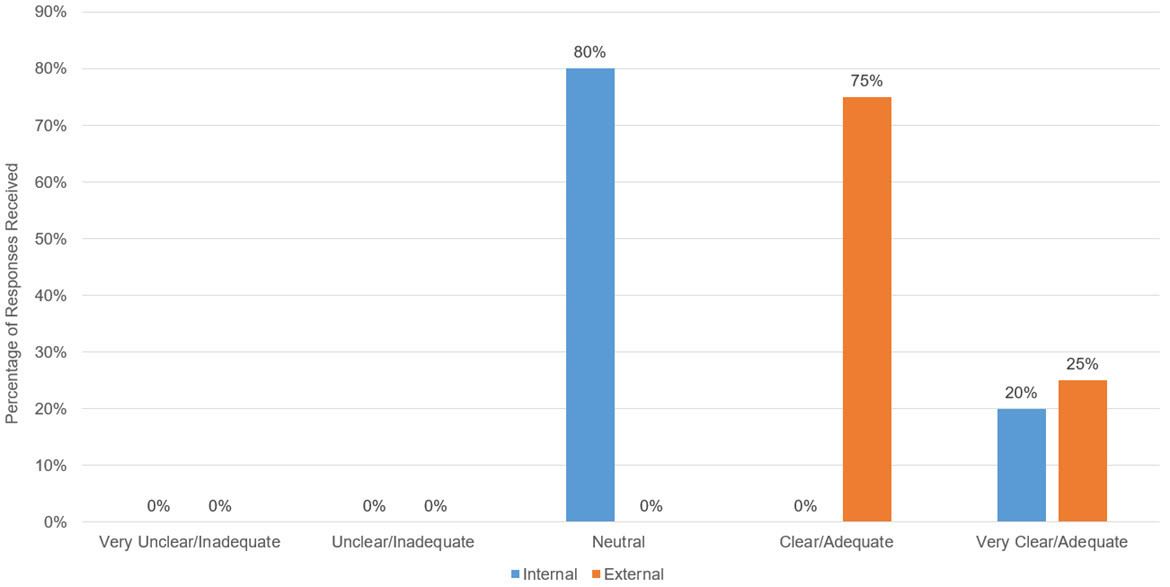

- Figure 26 - Overall Perception of Clarity and Adequacy of the Communication Between Key Program Stakeholders

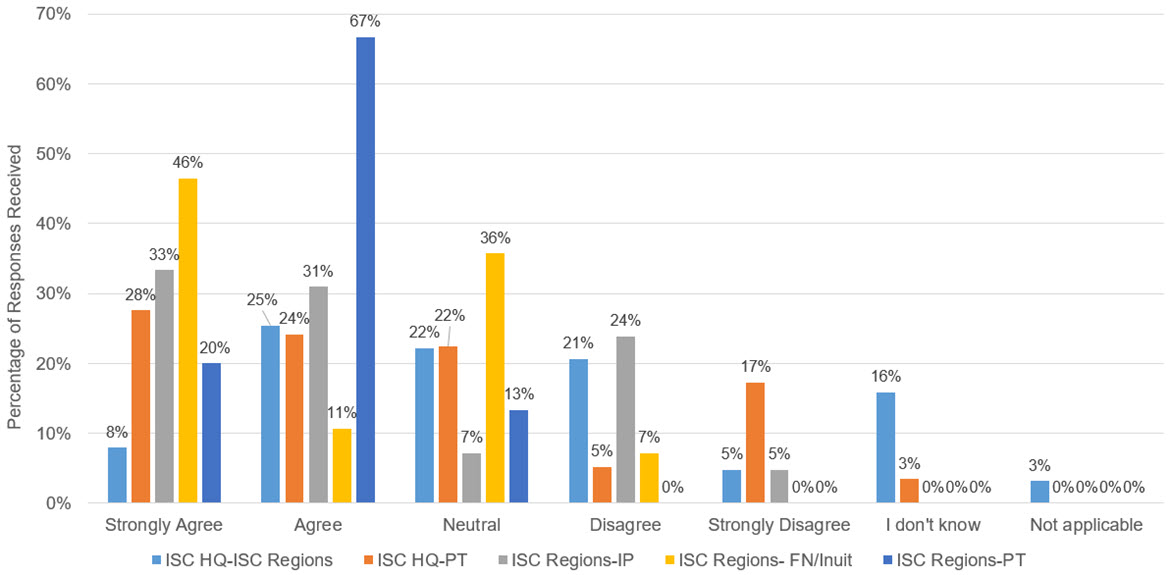

- Figure 27 - Perception of partners that there is effective communication between program partners

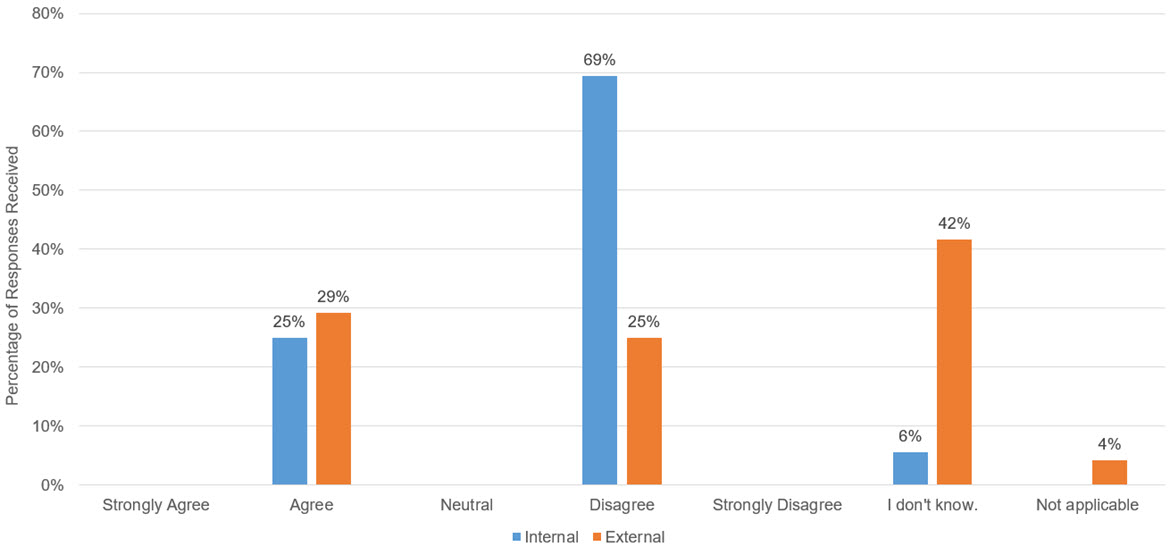

- Figure 28 - The role and responsibilities of this program and its staff are clearly defined, well understood and communicated effectively

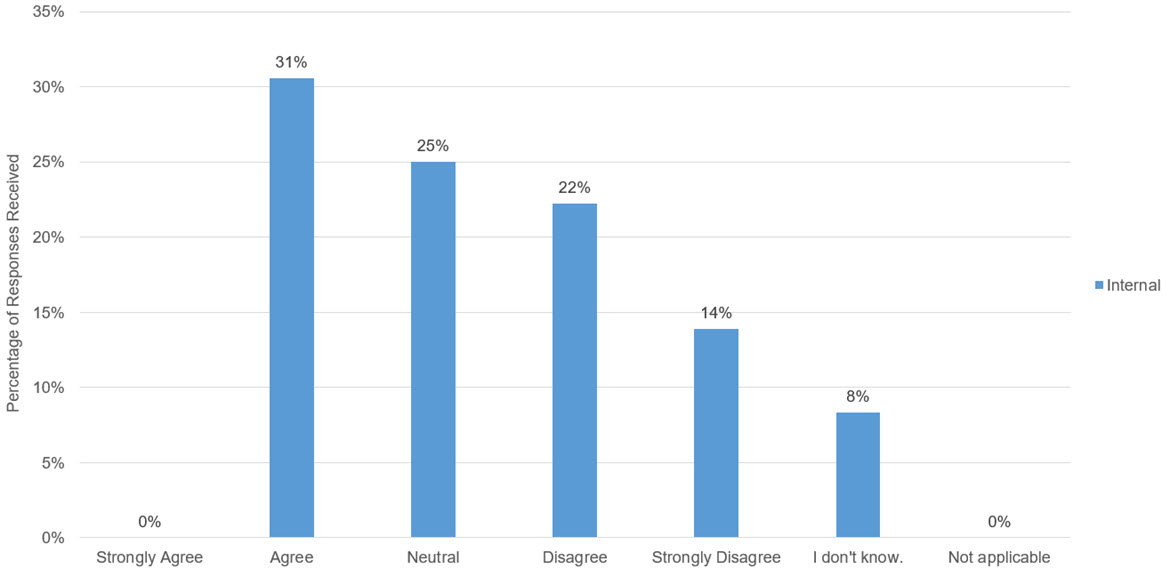

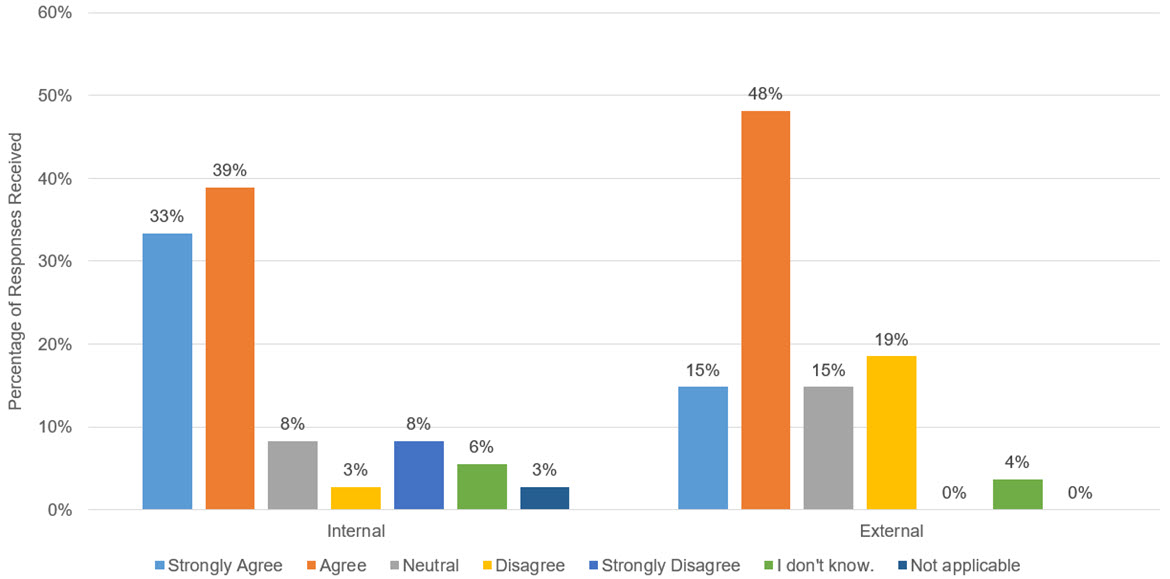

- Figure 29 - Information about service transfer is communicated effectively to me and my team

- Figure 30 - Which other health infrastructure support services do you collaborate with to perform your duties?

- Figure 31 - Effectiveness and Productivity of Relationships Between Programs

- Figure 32 - Are there other health infrastructure support services that collaboration with would increase benefits to First Nations and Inuit?

- Figure 33 - First Nations and Inuit who access health infrastructure are equal partners in planning, developing, and monitoring to make sure it meets their needs and to achieve the best outcomes

- Figure 34 - Program Annual Expenditures

- Figure 35 - Number of Program FTEs by Cluster Program Fiscal Year 2015-16 to Fiscal Year 2020-21

- Figure 36 - Staffing is adequate in ISC Regional Offices to support health service(s) delivery

- Figure 37 - Staffing is adequate in First Nations and Inuit communities to support health service(s) delivery

Table of Tables

- Table 1 - Cluster Programs' Expenditure and Full-Time Equivalent

- Table 2 - Evaluation Methodologies

- Table 3 - Limitations

- Table 4 - Self-Reported Health Issues

- Table 5 - Treasury Board Reporting Performance Indicators by Cluster Program

- Table 6 - Number of First Nations Health Facilities and Centres that are Accredited or in Process by Region

- Table 7 - Number of Telehealth Sessions Delivered by Type

- Table 8 - Number of Health Field Bursaries Awarded from Fiscal Year 2015-16 to Fiscal Year 2019-2020

- Table 9 - Number of Award Recipients from Fiscal Year 2015-16 to Fiscal Year 2019-2020, by Indigenous Identity

- Table 10 - Training Provided to Indigenous Community Workers Funded Through HHR from Fiscal Year 2015-16 to Fiscal Year 2020-21

- Table 11 - HFP Progress Against Select Performance Indicators

- Table 12 - Summary of COVID Special Expenditures by Cluster Program

- Table 13 - Summary of FTEs by Cluster Program and Year Over Year Percentage Change

Executive Summary

The Cluster Evaluation of Health Infrastructure Support for First Nations and Inuit was outlined in Indigenous Services Canada's (ISC) Five-Year Evaluation Plan 2020-21 to 2024-25 and conducted in compliance with the Treasury Board of Canada Policy on Results. This Evaluation took the form of a cluster evaluation with six programs in scope from First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB). The programs in scope for this evaluation were: Health Planning and Quality Management (HPQM); Health Services Integration Fund (HSIF); Quality Improvement and Accreditation Program (QIAP); Health Facilities Program (HFP); eHealth Infostructure Program (eHealth); and Health Human Resources (HHR). The period covered by the Evaluation was fiscal years 2015 to 2021. In the context of this evaluation, health infrastructure support refers to the various elements of a viable health system, including health planning, accreditation, quality improvement, governance, health facilities, and integration.

The cluster approach allows for a systems perspective, presenting an opportunity to understand how these programs work together and what impacts they collectively contribute. All three streams of enquiry (relevance, effectiveness, and efficiency) were in scope for this Evaluation. Additionally, Service Transfer was evaluated through the lens of all three streams of enquiry.

Several methodologies were used to answer the evaluation questions such as a document and literature review, a survey and a total of 109 interviews made with internal and externals respondents including 6 case studies from across Canada. Evaluation questions that guided the methodology of this evaluation, and associated indicators, can be found in Appendix A – Evaluation Matrix. Limitations occurred in gathering program data and reaching respondents during the 6 months allocated by the study. The tools used to collect data and their limitations are discussed further in the body of this report and in Appendix B – Key Informants and Appendix C – Survey Participants.

Service transferFootnote 1 is defined by ISC as the transfer or shift of control of federally administered programs, policies, and services to First Nations and Inuit-led organizations, supporting self-determination and First Nations and Inuit control in designing, developing, and implementing their own program, services, and policies to address their unique needs and priorities and respect distinct cultural practices. The evaluation recognizes that service transfer is a continuum and can include small "t" transfer (e.g., devolution of single programs to people in First Nations and Inuit communities that may still follow federal government regulations) as well as big "T" transfer (e.g., Health Transformation, where a First Nations or Inuit organization is funded to develop a governance structure and assume full control of the federally funded programs and services). In the context of this evaluation, the findings related to service transfer that are presented are in reference to the full continuum of service transfer to recognize the unique needs of people in First Nations and Inuit communities.

Key Findings

Relevance

First Nation and Inuit have a complex and expansive list of health needs that need to be addressed by the programs in the Cluster and beyond to improve First Nations and Inuit access to quality health care services. People in First Nations and Inuit communities require health services that are identified based on specific community needs, in consideration of social determinants of health, cultural safety and humility, and level of integration across the health services continuum. In order to achieve this, First Nations and Inuit need the resources to overcome externally generated social and policy obstacles that impede access to adequate care.

Both internal and external interviews indicate that the objectives of the Cluster programs are well aligned with the identified health needs of First Nations and Inuit, as well as the Canadian Patient Safety and the Declaration of Cultural Safety and Humility. However, there are significant improvements required in the way the programs in the cluster are designed and delivered to ensure achievement of these objectives through the Cluster programs.

The relevance of the programs, in regard to the needs they were designed to address, is evident. There was a notable trend across the country towards needs for appropriate and adequate health facilities, access to eHealth technologies, trained and educated community-based health care workers, accredited health centres, and improved collaboration between government levels to move towards self-government and autonomy. Yet, the level of need amongst these common areas differed by region and by specific community. Further, First Nations and Inuit have unique needs related to their population demographics and geographical locations. These variations imply that the Cluster programs would be most effective if designed with the appropriate level of flexibility to allow programs to adapt resource allocation to align with local needs.

Relationships

Overall, the relationships between program partners varies significantly between program type and region due to a number of factors such as region-specific agreements as well as program funding levels. Relationships between ISC Headquarters (HQ) and ISC Regional Operations, ISC Regional Operations and First Nations and Inuit, and ISC Regional Operations and Provincial governments were highlighted as the ones most in need of improvement, with partners citing challenges with consistent staff turnover, ineffective communication regarding funding, and lack of engagement. There is a need for increased, intentional collaboration amongst key program partners, with particular attention paid to clarifying roles and responsibilities between ISC HQ and ISC Regional Operations, and improved communications around service transfer (definition and clarity on how to effectively support it). Productive relationships between each Cluster program were noted to be rare, despite a shared ultimate outcome and certain thematic overlaps of services. There is an opportunity to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the Cluster programs through increased collaboration and knowledge sharing. The importance of relationship building was a consistent trend throughout the evaluation.

Program Outcomes

Program partners noted key challenges that require improvement, particularly around program delivery and administration processes, performance measurement, and reporting. Areas for improvement highlighted included: access to sustainable long-term funding, an improved recognition of local needs, enhanced funding for and focus on training, and First Nations and Inuit awareness of programs. Further, challenges were raised in relation to performance measurement and reporting as a result of data limitations, a misalignment of western data-based reporting approaches to First Nations and Inuit ways of knowing, and the burden of reporting amidst already overcapacity and understaffed health centres in communities.

The value and impact of the Cluster programs, including improving access to and quality of health care for First Nations and Inuit was highlighted by most partners consulted. Interviews indicated that progress has been made towards empowering First Nations to take on the planning and management of health services and building capacity and capabilities within First Nations to prepare for health service transfer.

However, the limited resources, both financial and human, was highlighted as a prominent obstacle impeding the achievement of the Cluster programs' intended outcomes during the evaluation scope period. Additionally, further challenges were highlighted in the impact the pandemic had on timelines and resources, the lack of flexibility of program parameters compared to First Nations' needs, the inability to secure sustainable funding, and the turnover in staff within the Department as an impediment to building lasting relationships and achieving progress towards the Cluster programs' intended outcomes.

Though not initially designed as a Cluster, there is a clear compatibility of the Cluster programs regarding their objectives and desired outcomes. For example, one of the criteria which much be met in order to be accredited, a health centre must put in place a health plan, which is a key output of the HPQM program. Further, to ensure proper physical infrastructure is built in health facilities, eHealth technologies are often required at the onset. Despite the complementarity of program objectives, the programs were found to operate in siloes, with very limited collaboration across the spectrum when delivering programs. This implies an opportunity to improve efficiencies and achievement of progress towards objectives through increased, early collaboration between programs. Consideration should be made to identify points of integration between programs (with each other as well as with other Departmental programming outside of the Cluster) and highlighting opportunities to work together to achieve common goals in shared regions of operation.

The effectiveness of this cluster is dependant on the level of resources invested in actualizing its objectives. There is a disconnect between the scope of the outcomes and the resources available to programs, and in turn First Nations and Inuit, which may be a result of a lack of integrated strategic and operational planning. Consideration should be made to review the priorities of the Cluster programs as a system while aligning with the new Departmental Results Framework put in place starting 2023-24 and assessing the feasibility and identifying opportunities to increase efficiencies within programs.

Best Practices

Based on external research and interviews, the evaluation noted the following best practices and lessons learned, particularly with regards to how the Cluster programs' design and delivery can be improved:

- The importance of data collection was noted as valuable to understand changes over time. In particular, supporting First Nations and Inuit data sovereignty is required to ensure information that is shared truly reflects First Nations and Inuit needs and priorities, including access to culturally safe health care.

- The value of building respectful and longstanding relationships with First Nations was repeatedly emphasized in interviews, along with a clear understanding of the Department's role. It was noted that two-way feedback facilitates an understanding of what aspects are working well for First Nations and what is not.

- Building communication mechanisms and networks for First Nations and ISC staff alike to share knowledge, best practices, and lessons learned was highlighted as valuable in supporting continued progress. Interviews also emphasized the role that effective documentation of knowledge by both ISC staff and people in First Nations communities plays in supporting knowledge transfer and building expertise.

- Breaking down barriers between services, sectors, organizations, and levels of government is key to promoting a more wholistic view of health care service delivery for First Nations and Inuit. There are opportunities for ISC programs to be better integrated to address social determinants of health.

These best practices are aligned to ISC's vision and mandate for health service transfer.

Impacts of COVID-19

The pandemic highlighted the severity of health needs of people in First Nations and Inuit communities as well as shortages and inequities related to access to appropriate health facilities, eHealth technologies, skilled community-based workers, and governance and planning structures to manage public health crises.

The global pandemic had significant impacts in the delivery of health services to First Nations, including limiting both access in and out of communities during lockdown measures and diverting resources towards pandemic response and away from other existing health needs and priorities. However, positive impacts were also noted, including a notable increase in efficiency in both funding releases from the federal government and program delivery, as well as an increase in demand and appreciation of the value of the intended outcomes of programs, particularly eHealth, Accreditation and Health Facilities. It also highlighted opportunities for innovation in program design and application of resources. The Cluster programs spurred the consideration of lessons learned, particularly around emergency preparedness and key priorities in health services delivery.

The COVID-19 pandemic served as the ultimate representation of the value of appropriately governed health facilities with the expertise, capacity, and resources to have emergency preparedness and crisis management plans in place. It also allowed First Nations and Inuit demonstrate what they are capable of when adequately supported. The ability of people in First Nations and Inuit communities, with support from ISC, to pivot and adapt rapidly in order to carry out the pandemic response in addition to meeting regular health needs was commendable. Programs were creative in leveraging new partners to provide added value to the pandemic response. For example, HHR partnered with the Red Cross and the First Nations Health Managers Association (FNHMA) Help Desk for Indigenous Leadership to provide First Nations with a trustworthy communication channel through which they could seek advice or be directed to the necessary resources to help them navigate the pandemic, independent of the government. Prioritization of the pandemic response resulted in increased efficiency and innovations undertaken by people in First Nations and Inuit communities. Moreover, the challenges faced by health services such as the inability to access communities in lockdown, labour shortages, or the lack of connectivity for virtual services, demonstrated the critical value of what the Cluster programs aim to achieve.

Evaluation Recommendations

Therefore, it is recommended that ISC:

- Leveraging existing needs assessments, engagement efforts, and consultations, develop a funding approach that addresses funding gaps and provides flexibility and sustainability to the programs evaluated.

- FNIHB works with First Nation and Inuit partners to co-develop and begin to implement a strategy – including identifying partners, approach and timing – to build capacity among Indigenous health leaders, health service providers, and supporting roles to increase opportunities for training and knowledge sharing between communities.

- To allow for uniform and flexible program application to equitably serve communities, FNIHB must:

- Perform an assessment of internal human resourcing to inform an internal human resources strategy in FNIHB that appropriately staffs and retains employees within the programs evaluated; and

- Create mechanisms to ensure program staff have common knowledge and understanding between and within evaluated programs and foster ongoing opportunities for knowledge exchange.

- In order to achieve a more wholistic and effective approach to service transfer, an alignment and integration between evaluated programs within FNIHB and ISC's broader vision of service transfer is required. It is recommended that FNIHB works with First Nations and Inuit, as well as ISC Strategic Policy Sector and Regional staff, collaborate to:

- Develop a workplan to communicate the evaluated programs' visions of transfer that are aligned with department's service transfer approach and vision; and

- Conduct an assessment that identifies commonality and redundancies between evaluated programs to support integration of programs and gradual transfer of services.

- FNIHB works with partners to develop a meaningful performance measurement strategy with the Chief Finances, Results and Deliver Officer Sector's (CFRDO) Results and Delivery Unit and supporting data collection and management strategy with Chief Data Officer (CDO) and Chief Information Officer (CIO) to support Indigenous data sovereignty in health services.

Management Response and Action Plan

Evaluation Title: Cluster Evaluation of Health Infrastructure Support for First Nations and Inuit

Management Response

This Management Response and Action Plan (MRAP) has been developed to address recommendations resulting from the Cluster Evaluation of Health Infrastructure Support for First Nations and Inuit, which was finalized by ISC Evaluation. This Evaluation took the form of a cluster evaluation, grouping together six programs in scope from First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB). The programs in scope for this evaluation were: Health Planning and Quality Management (HPQM); Health Services Integration Fund (HSIF); Quality Improvement and Accreditation Program (QIAP); Health Facilities Program (HFP); eHealth Infostructure Program (eHealth); and Health Human Resources (HHR). Although the British Columbia Tripartite Relations program was not formally evaluated as part of this cluster evaluation, it was included in the scope with the intent to learn from its design and delivery model and glean best practices and lessons learned related to transfer of health services. The period covered by the Evaluation was fiscal years 2015 to 2021.

The cluster approach allows for a systems perspective, providing the opportunity to understand how programs work together and what impacts they collectively contribute. Since the commencement of the evaluation, the Department updated its Departmental Results Framework as of April 1, 2023, realigning its programs inventory, including the creation of the new Health Systems Support Program, aligning the e-Health Infostructure sub-program as part of the Primary Care Program and aligning the Health Facilities sub-Program, as part of the Community Infrastructure Program.

FNIHB recognizes the key findings highlighted by the evaluation related to the following themes: relevance of the programs, program outcomes, relationships, best practices, and impacts of COVID-19.

The evaluation provides five recommendations, all of which are accepted by FNIHB, and the attached Action Plan identifies specific activities to implement these recommendations.

The Department has reviewed and assessed the recommendations and will proceed with their implementation over a two-year period and in the context of Indigenous partners' visions and priorities, expressed during two foundational engagements that are underway –

- engagement with Indigenous partners on the co-development of distinctions-based+ Indigenous health legislation to improve access to high-quality, culturally-relevant and safe health services; and

- engagement on the design and implementation of the Indigenous Health Equity Fund.

An annual review of this Management Response and Action Plan will be conducted by the Departmental Evaluation Committee to monitor progress and activities.

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

|

We agree with this recommendation. Equitable, adequate, sustainable, inclusive, and flexible funding that is available to Indigenous Peoples is one of the 9 key themes conveyed by Indigenous Peoples about the state of Indigenous health in Canada and their vision of what to include in distinctions-based+ Indigenous health legislation to improve access to high-quality, culturally-relevant, and safe health services. In particular, Indigenous groups want more direct funding models, fewer reporting burdens, and funding formulas that are holistic and needs-based. While Indigenous health legislation provides the approach to redesign and rethink existing Indigenous health funding models more broadly, as well as to secure funding for Indigenous groups that is equitable, adequate, sustainable, inclusive and flexible, existing needs assessments of program areas within the evaluation provide a basis for initial efforts to address some of these changes. In this regard, the following actions could be taken:

|

|

Start Date: Completion: |

|

We agree with this recommendation. Supporting and building capacity in health human resources is one of the 9 key themes conveyed by Indigenous Peoples about the state of Indigenous health in Canada and their vision of what to include in distinctions-based+ Indigenous health legislation to improve access to high-quality, culturally-relevant, and safe health services. In particular, Indigenous partners identified the need for health care workers to develop locally-based cultural competencies to provide person-centred care and build relationships between providers, clients and communities. Indigenous partners have highlighted the importance of mandatory training in Indigenous cultural competency, anti-racism, anti-oppression and trauma-informed care. FNIHB is committed to continue working with First Nations and Inuit partners to identify and co-develop initiatives that support locally-based cultural competencies, training availability, knowledge sharing and enhancement of capacity among health Indigenous leaders and service providers. In this regard, the following actions could be taken:

|

|

Start Date: Completion: |

|

We agree with this recommendation. FNIHB is continuously exploring new and innovative retention and recruitment strategies, such as the nursing health human resources framework. In addition, together with Regions, FNIHB is implementing human resourcing priorities under Better Together – an organizational culture initiative that aims to foster an environment that supports all FNIHB staff and promotes wellness in our work while also addressing barriers and behaviours that negatively impact wellness. These priorities include:

In this regard, the following actions could be taken:

|

|

Start Date: Completion: |

|

We agree with this recommendation. The Department is committed to working in partnership with Indigenous Peoples to advance the priorities of First Nations and Inuit, including those of intersectional groups (i.e., Indigenous youth, women, urban, and 2SLGBTQQIA+ Peoples), when it comes to healthcare and ensuring improved access to high quality, culturally relevant, safe care. To this end, in 2019, the Government of Canada committed to hearing from Indigenous Peoples to identify those priorities and consider whether and how they might be advanced by means of federal legislation, as well as to working together to co-develop potential legislative options to address them. The co-development of distinctions-based+ Indigenous health legislation is an opportunity to advance the following objectives:

In this regard, the following actions could be taken:

|

|

Start Date: Completion: |

|

We agree with this recommendation. To set the appropriate context for our response, the Department has updated its Departmental Results Framework as of April 1, 2023, realigning its programs inventory, including the creation of the new Health Systems Support Program, the e-Health Infostructure sub-program (as part of the Primary Care Program) and the Health Facilities sub-Program (as part of the Community Infrastructure Program). This work has led to the current review and update of the branch's Performance Information Profiles (PIPs), which encompass performance measurement strategies in collaboration with the CFRDO Results and Delivery Unit. In this regard, the following actions could be taken:

While remaining respectful of partners' own priorities and goals related to Indigenous data sovereignty in health services, over the next 2 years FNIHB will continue to remain abreast of discussions with partners (e.g., First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) information sharing mechanisms) led by the CDO and CIO through established governance / committees / tables as part of departmental efforts regarding control and transfer of data. In this regard, the following actions could be taken:

|

|

Start Date: Completion: |

1. Introduction

The overall purpose of the evaluation was to examine a set of health infrastructure support programs at Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) (or the 'Cluster') in fulfilment of ISC's Five-Year Evaluation Plan 2020-21 to 2024-25 and Treasury Board of Canada requirements for program evaluations.

This Evaluation is taking the form of a cluster evaluation to determine if ISC's expected outcomes are being met; to support ISC with alleviating a backlog of evaluations due under the Treasury Board Section 42.1(1) of the Financial Administration Act requirements; and to alleviate the burden on program areas by only evaluating programming once in the next five-year period. The cluster approach allows for a systems perspective, allowing for the opportunity to understand how programs work together and what impacts they collectively contribute.

There are six programs that compose this cluster, all delivered by FNHIB. A short profile of these programs objectives and outcomes are presented below. The overarching logic model developed by ISC Evaluation for this cluster of programs (hereinafter referred to as "the Cluster") is outlined in Appendix D – Cluster Logic Model.Footnote 2 All programs noted below, except eHealth Infostructure Program, are delivered to First Nation and Inuit. However, delivery to Inuit is limited to only a few projects in most instances. eHealth Infostructure Program is only delivered to First Nations.

Health Planning, Quality Management and Systems Integration (HPQM&SI) Program: This program administers funding agreements and direct spending to increase the capacity of First Nations and Inuit to design, manage, evaluate, and deliver health programming.Footnote 3 The focus of the program is on health planning by First Nations and Inuit for First Nations and Inuit and thus directly contributes to the overall goal of "increasing the capacity of First Nations and Inuit to design, manage, evaluate, and deliver health programs and services".Footnote 4

The program includes the following three sub-programs:

- Health Planning and Quality Management

- Health Services Integration Fund

- Quality Improvement and Accreditation

-

Health Planning and Quality Management (HPQM)

This program provides guidance to regions, who in turn work directly with First Nations and Inuit on creating health and wellness plans. The program provides funding for these plans through funding agreements. This program collaborates with the First Nations Health Managers Association (FNHMA) to develop tools to support community health and wellness planning and provides national oversight and support to FNIHB regions for funding arrangement management and health and wellness planning. The program also supports improving health services and programming by incorporating quality improvement activities in health programs (e.g., accreditation and evaluation of health programs).Footnote 5

-

Health Services Integration Fund (HSIF)

This fund supports collaborative planning and multi-year projects aimed at better meeting the healthcare needs of First Nations and Inuit by working with provincial and federal levels of government and creating partnerships to integrate federally and provincially/territorially funded health services in First Nations and Inuit communities; improving access to healthcare for First Nations and Inuit; and increasing the participation of First Nations and Inuit in health programming design, delivery, and program evaluation. HSIF is regionally implemented throughout the country with participation and support from the regional advisory committees in some regions.Footnote 6

-

Quality Improvement and Accreditation Program (QIAP)

The program contributes to advancing the self-determination and capacity for health services for people in First Nations and Inuit communities that meet their needs to improve health outcomes. The program accomplishes this by facilitating the uptake of accreditation and recommending Quality Improvement activities to increase community-based health human resource capacity of First Nations and Inuit to design, manage, evaluate, and deliver health programs and services.

Health Facilities Program (HFP)

This program aims to support the delivery of health programs and services through investments in health infrastructure. It provides funding to eligible recipients for: planning, design, construction, acquisition, leasing, expansion, renovation, security services, and/or operation and maintenance of health infrastructure. The program also funds preventative and corrective measures to improve the condition of health infrastructure or to maintain or restore compliance with building codes, environmental legislation, and occupational health and safety standards. These activities aim to provide First Nations and Inuit with the space required to deliver healthcare services safely and efficiently for First Nations and Inuit. Health infrastructure includes health facilities, substance use / addiction treatment centres, Aboriginal Head Start On-Reserve (AHSOR) space, health professional residences / accommodations and support infrastructure. These buildings support the delivery of health programs and services.

eHealth Infostructure Program (eHealth)

The objective of the eHealth Infostructure Program is to provide the "right information to the right people at the right time" to support First Nations in being connected, informed, and healthier, and to enable front-line healthcare workers working in First Nations and Inuit communities to improve First Nations and Inuit health through eHealth programming.Footnote 7

The goal of the activities currently being carried out by the eHealth program is to improve the efficiency of health care delivery to First Nations through the use of eHealth technologies for the purpose of defining, collecting, communicating, managing, disseminating, and using health data.Footnote 8Footnote 9

Health Human Resources (HHR)

This program contributes to the strengthening of Indigenous social services, including healthy living and child development, community care, kindergarten to post-secondary education services, familial support, and communicable disease prevention.Footnote 10

The program's objectives are to increase the number of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis practicing in healthcare, and to increase the number of qualified individuals working in healthcare delivery in First Nations and Inuit communities. The program is delivered through two streams: the first provides scholarships and bursaries for Indigenous students pursuing health careers and is delivered in partnership with Indspire, and the second provides training and certification for community-based workers and health managers to improve the quality and consistency of healthcare services in First Nations and Inuit communities.Footnote 11

In addition to the six programs evaluated as part of this Cluster, the British Columbia Tripartite Relations (BCT) was included in this evaluation, not to evaluate its performance but rather to learn from the model experience. The BC Tripartite Relations program is intended to promote tripartite relationships between the federal and provincial levels of government with First Nations. The objective of this program is to enable the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) in BC to develop and deliver quality health services to First Nations living in BC that feature closer collaboration and integration with provincial health services. As the BC Tripartite Relations was evaluated recently (in 2019), the Cluster evaluation noted any best practices and/or lessons learned from the BC Tripartite Relations to support the objective of the evaluation. The BCT may serve as a model for new models of health service delivery systems across the country and its impact on systems integration may provide valuable lessons learned on further transfer of other activities.

A summary of the Cluster's programs' expenditure and full-time equivalent (FTE) informationFootnote 12 over the evaluation period is provided in the tables below.

| Cluster Programs | Program Expenditures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Year 2015/16 | Fiscal Year 2016/17 | Fiscal Year 2017/18 | Fiscal Year 2018/19 | Fiscal Year 2019/20 | Fiscal Year 2020/21 | |

| Health Planning and Quality Management (HPQM) | $108,307,252 | $111,311,408 | $116,762,360 | $132,531,553 | $125,635,240 | $131,437,339 |

| Health Services Integration Fund (HSIF) | $8,061,749 | $19,586,573 | $14,498,900 | $37,661,337 | $41,355,707 | $40,365,229 |

| Quality Improvement & Accreditation (QIAP) | $5,203,010 | $5,329,828 | $5,598,299 | $6,333,099 | $5,684,666 | $6,143,294 |

| Health Facilities Program (HFP) | $89,444,707 | $167,948,252 | $197,348,222 | $172,439,143 | $148,278,066 | $149,189,768 |

| eHealth Infostructure Program (eHIP) | $24,367,982 | $25,910,204 | $26,874,347 | $25,725,674 | $28,038,393 | $30,889,468 |

| Health Human Resources (HHR) | $5,753,907 | $5,651,730 | $8,796,364 | $5,808,989 | $5,901,977 | $2,722,649 |

| Cluster Programs | Program FTEs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Year 2015/16 | Fiscal Year 2016/17 | Fiscal Year 2017/18 | Fiscal Year 2018/19 | Fiscal Year 2019/20 | Fiscal Year 2020/21 | |

| Health Planning and Quality Management (HPQM) | 32.34 | 35.64 | 30.61 | 23.00 | 27.60 | 32.20 |

| Health Services Integration Fund (HSIF) | 7.85 | 5.82 | 5.87 | 3.17 | 2.45 | 2.76 |

| Quality Improvement & Accreditation (QIAP) | 7.09 | 8.36 | 4.00 | 2.35 | 3.22 | 5.00 |

| Health Facilities Program (HFP) | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | 48.08 | 48.94 | 57.39 |

| eHealth Infostructure Program (eHIP) | 27.66 | 27.58 | 22.88 | 20.69 | 22.21 | 24.46 |

| Health Human Resources (HHR) | 1.60 | 1.50 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Scope and Evaluation Issues

All three streams of enquiry (Relevance, Effectiveness, and Efficiency) were in scope for this Evaluation. Additionally, Service Transfer was evaluated through the lens of all three streams of enquiry. The period covered by the Evaluation was fiscal years 2015 to 2021. In the context of this evaluation, health infrastructure support refers to the various elements of a viable health system, including health planning, accreditation, quality improvement, governance, health facilities, eHealth, and integration.

Service transferFootnote 13 is defined by ISC as the transfer or shift of control of federally administered programs, policies, and services to First Nations and Inuit-led organizations, supporting self-determination and First Nations and Inuit control in designing, developing, and implementing their own program, services, and policies to address their unique needs and priorities and respect distinct cultural practices. The evaluation recognizes that service transfer is a continuum and can include small "t" transfer (e.g., devolution of single programs to people in First Nations and Inuit communities that may still follow federal government regulations) as well as big "T" transfer (e.g., Health Transformation, where a First Nations or Inuit organization is funded to develop a governance structure and assume full control of the federally funded programs and services). In the context of this evaluation, the findings related to service transfer that are presented are in reference to the full continuum of service transfer to recognize the unique needs of people in First Nations and Inuit communities.

The following questions guided the methodology of this evaluation. A complete list of questions, indicators and evaluation methods is found in Appendix A – Evaluation Matrix.

Relevance:

- What are the needs that this cluster of health programs for First Nations and Inuit should address? Are the needs still relevant and/or have new needs arisen?

- Are the objectives of this cluster of programs (i.e., what the programs are designed to do) aligned to the needs of First Nations and Inuit?

- Is the departmental goal of service transfer aligned to the needs of First Nations and Inuit?

Effectiveness:

- To what extent has each of the programs included made progress toward the achievement of their expected outcomes?

- How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact the delivery of the programs and their ability to support First Nations and Inuit?

- How have the programs in the Cluster worked towards ensuring the eventual transfer of departmental responsibilities to First Nations and Inuit, as mandated by the department?

- What aspects of the programs are working well and what aspects need improvement?

- How effective/productive are the relationships between partners in each of the programs (e.g., between ISC Headquarters and regional offices, First Nations and Inuit, implementing partners, provincial and municipal governments, etc.) and between programs?

Efficiency:

- How cost effective is the design and delivery of the programs included in this health infrastructure support cluster?

- Are there ways to make them more cost effective?

- Is the allocation of funding to and within each of the programs appropriate to achieve the expected outcomes?

2.2 Design and Methods

The evaluation was led by a team from the Evaluation Directorate within ISC. The Methodology Report was finalized in May 2022, with primary data collection occurring from June 2022 to January 2023.

The evaluation used a mixed methods approach and gathered data through various lines of evidence, including:

| Methodologies | Description |

|---|---|

| Documentation, program data, and file review | The evaluation team reviewed documentation to collect both quantitative and qualitative data related to ISC's processes and activities. This included Performance Information Profiles (PIPs), program performance data as available, previous evaluation reports, as well as any additional documentation identified during interviews. |

| Literature and media review | The evaluation team conducted a review of literature and media publications related to elements of First Nations health governance and infrastructure on reserve and in the Northern Territories of Canada, and in relation to impacts of COVID-19. Literature within both the domestic and international contexts was reviewed. Over 50 external literature sources were reviewed, including: journal articles; academic reports; non-governmental organization reports; and relevant journal, newspaper, and online media articles. |

| Key informant interviews and focus groups (n=109) |

The objective of key informant interviews and focus groups was to collect in-depth information, performance data, and stories based on stakeholder experiences with one or more of the Cluster programs. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposeful sample of internal key informants, including:

A total of seven (7) focus groups were conducted with ISC Regional Staff. One focus group per program was held, and representatives from each region per program were in attendance. The total number of participants across all focus groups was 57. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a stratified random sample of external key informants, including:

For participants who declined the request to be interviewed, the Evaluation Team accepted written responses to the interview questions. A total of 6 written responses were collected. In total, 109 key informants were engaged with to provide information for this evaluation. |

| Survey |

A survey was administered to both internal and external respondents to gather both qualitative and quantitative data for the evaluation. 74 total responses (16 from First Nations Representatives; 18 from Implementing Partners; and 40 from ISC Regional Staff) were received. Participation in the survey was voluntary and as such is not representative of the perceptions of the entire population of internal and external program partners. |

| Case studies (n=6) | The objective of the case studies was to gain an in-depth understanding of First Nations' experiences with the Cluster programs as well as identify any potential lessons learned in program delivery. Each case study involved interviews, documentation review, and external research. 6 of 6 selected case study contacts completed interviews. |

The lines of evidence and their relationship with Key Evaluation Questions are outlined in Appendix A – Evaluation Matrix. Appendix E – Case Study Background Information provides additional details on the case studies represented in this report.

This evaluation faced challenges that limited a complete appraisal. The limitations of the evaluation and their associated mitigation strategies are described below:

| Limitations | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|

| Lack of a robust performance measurement strategy: Through consultations with ISC staff, the evaluation noted that the program indicators used to assess performance (as defined in the PIPs) were not consistently used. Program performance information may not have been collected, tracked, monitored, or reported on in a consistent manner (i.e., within the evaluation scope period), or the programs noted that the indicators were no longer relevant and were in the process of updating their PIPs. This limited the amount of quantitative data the evaluation was able to analyze and report on.Footnote 16 |

|

| Inconsistency in external interviewee regional coverage and low interview participation rate: There were challenges in obtaining a consistent and high external interviewee (e.g., First Nations Representatives, Implementing Partners) participation rate across all regions. Some ISC staff were unable to provide the evaluation team with contact information for external partners. Some external partners either chose not to participate or did not respond to the participation request. |

|

| Issues with quantitative data quality: Given FNIHB’s programs moved from Health Canada to Indigenous Services Canada during the evaluation period, different IT systems and coding were used to manage funding and human resources. For the evaluation, this resulted in issues with data consistency. |

|

2.3 Project Governance

The evaluation team used a participatory and consultative approach through engagement with an Evaluation Advisory Committee (EAC) chaired by the Director of Evaluation. Members of this committee were made up of directors within ISC who are responsible for the oversight of the Cluster programs in FNHIB. They, along with representatives from the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), commented on the purpose and scope of the evaluation, the key evaluation questions, and the evaluation methodology. Committee members were asked to: review the methodology report, including the data collection instruments; validate quantitative data and the evaluation preliminary findings following data collection; and review the draft evaluation report.

3. Findings

3.1 Relevance

Evaluation Question: What are the needs that this cluster of health programs for First Nations and Inuit should address? Are the needs still relevant and/or have new needs arisen?

To conduct this assessment, it is necessary to ensure a wholistic understanding of what the health needs of First Nations and Inuit are in the present day, and how they may have evolved since 2015 (the beginning of the evaluation scope period).

IndigenousFootnote 17 peoples in Canada face significant inequities in access to and quality of health care services. The First Nations Health Authority depicted a First Nations' perspective of health and wellness visually (as seen in Image 1), encompassing several elements, including: social, economic, environmental, and cultural.Footnote 18 Based on both the western and Indigenous perspectives of the wholistic definition of health, a sufficient understanding of the core health needs of First Nations and Inuit requires consideration of the social determinants of health, the specific barriers to access, and the specific health crises that First Nations and Inuit face as a result.

Text alternative for Figure 1 - FNHA depicted the First Nations' perspective of health and wellness (FNHA, n.d.)

Figure 1 is an image depicting a First Nations perspective of health and wellness. At the center of the figure is a five ring circle, with the inner most circle representing the human being, the second ring illustrating emotional, mental, spiritual, and physical, the third ring represents wisdom, respect, relationships, and responsibility; the fourth ring represents family, land, nations, and community, and the outermost ring, represents environmental, social, economic, and cultural health and wellness. Outside of the circle there are 21 silhouettes of people holding hands.

Finding #1: First Nations and Inuit experience significant social inequities that greatly impact access to quality and culturally safe health services.

The Government of Canada (GoC) acknowledges health and social inequities faced by Indigenous peoples in Canada.Footnote 19 The quality of an individual's health is heavily influenced by socioeconomic factors, with studies demonstrating that social determinants of health can account for 30-55% of health outcomes.Footnote 20 Half of all interviewees engaged in this evaluation highlighted the importance of understanding the social determinants of health, and the necessity to address these needs in order to see meaningful and sustainable improvements to Indigenous access to high quality health services. Specifically, interviewees and literature emphasized the need to address housing, economic adversity, connectivity, and racism and discrimination in the health care system to improve access to health and improved health outcomes for Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous Peoples face Insufficient Quality and Quantity of Housing

Canadians are currently facing a severe shortage of affordable housing, with housing demand significantly increasing from 2016 to present, while housing supply has not maintained the same pace.Footnote 21 As of 2021, 35.7% of First Nations living on reserve and 52.9% of Inuit living in Inuit Nunangat live in unsuitable and inadequateFootnote 22 housing.Footnote 23

56% of First Nations Representatives engaged in this evaluation specifically highlighted the impact that the acute shortage of housing has had on the health of First Nations, and the ability of health care workers to provide adequate care. The lack of housing availability, adequacy, and suitability impacts health, including health conditions (e.g., mould leading to asthma), increased spread of viral diseases due to overcrowding (e.g., as during the COVID-19 pandemic), and even leads to increased gender-based violence.Footnote 24 According to key informants, the lack of housing availability has also impacted communities' and health centres' abilities to recruit and retain health care staff as they are unable to offer temporary and stable housing in the community. As such, when Indigenous peoples seek education in health care professions, they are often required to leave the community to access employment opportunities and training. This further exacerbates existing challenges in the recruitment and retention of qualified health professionals in community to provide culturally safe and accessible care to remote or rural Indigenous patients.

Indigenous Peoples face heightened rates of Economic Adversity

The economic statusFootnote 25 of any individual has a significant impact on their ability to maintain their health and access services when needed. Notwithstanding the direct link economic status has to one's ability to access other key social determinants of health (i.e., ability to afford housing, food, and/or education) which impacts health status, it also directly affects an individual's ability to afford services that are not covered by provincial or territorial health insurance.

Indigenous peoples throughout Canada face higher rates of economic adversity.Footnote 26 First Nations and Inuit contend with barriers including higher cost of living (particularly in remote and rural areas), lower opportunity for employment, and lower comparative incomes.Footnote 27 Living in poverty has strong ties to substance use and increased violence in communities, which in turn impact both the physical and mental health of those residing within these communities, resulting in greater need for emergency services and mental health support programs.

Indigenous Peoples continued to face Social Exclusion, Anti-Indigenous Racism, and Discrimination

Social Inclusion

Experts categorize social inclusion as a determinant of health, as research shows that social exclusion can negatively impact both access to care and mental health and wellness.Footnote 28 Social exclusion is a result of social inequities, typically dictated by the way certain populations are marginalized and systemically excluded through social and economic policies and systems. Canada has acknowledged that Indigenous peoples are among four populations of people who have been denied equitable access to social services, including health, housing, and education.Footnote 29 To support addressing the social determinants of health, social prescribing was introduced to with the goal to increase collaboration between clients, staff and community providers to develop solutions. Social prescribing intends to function as a tool to complement medical care.Footnote 30

Anti-Indigenous Racism

Anti-Indigenous racism refers to racism directed specifically to Indigenous individuals. According to interviews, anti-Indigenous racism has both direct and indirect impacts on the health of people in First Nations and Inuit communities. Indigenous peoples have long been subjected to discrimination and poor treatment due to the deep-rooted and severely harmful assumptions and negative stereotypes that are directed at them. The federal government acknowledges that Indigenous peoples in Canada continue to face racism and discrimination in the healthcare system.Footnote 31 For example, a common stereotype is that Indigenous people experience substance addiction challenges (i.e., alcohol and drugs), and as a result, Indigenous patients are often dismissed or ignored when they seek medical help with symptoms assumed to be alcohol or drug-related. In many cases, Indigenous peoples face violent and hateful treatment in the health care system, leading to increased trauma, dismissal of medical challenges by health care professionals, and fear of seeking care.

According to research conducted and shared by a First Nation subject matter expert (SME), the trauma of colonialism and continued racism faced by Indigenous peoples have intergenerational repercussions that manifest through higher likelihood of physical maladies. Countless instances of abuse and mistreatment of Indigenous peoples within the health care system have resulted in preventable fatalities. Interviewees noted the need for prioritizing the recruitment and retention of human resources who are equipped to provide culturally safe care and support Indigenous peoples accessing safe and traditional medical practices and healing.

Further to physical health impediments, research has shown racism and discrimination can cause intense stress and trauma in victims.Footnote 32 These conditions are often linked to deeper mental illnesses (i.e., anxiety, depression) and can even cause addictions to alcohol or drugs.

As such, a significant number of interviews (29%), particularly among First Nations Representatives (67%) and Implementing Partners (60%), highlighted the need for trauma-informed, culturally sensitive health care services, citing racism and discrimination as a major barrier to health care for Indigenous peoples nationwide.

Indigenous Women and Girls

While being a member of any one designated group (e.g., women, persons with disabilities, racialized groups, etc.) already creates numerous barriers, the challenge becomes even greater when considering the impacts of intersectional identitiesFootnote 33. When assessing the impact of Indigeneity on access to health services, it is important to consider the unique challenges faced by Indigenous people who also identify as members of other designated groups. In particular, Indigenous women were highlighted by interviewees as a group that experiences challenges that differ from both Indigenous men and non-Indigenous women.

Callout Box 1: Research demonstrates that:

- The lack of access to culturally-responsive care exacerbates health concerns related to chronic illness and increases the need for additional health care providers. For example, a lack of access to care for diabetes results in additional need for foot care specialists.Callout Box 1 note 1

- Approximately 40% of First Nations adults on reserve are living with diabetes, compared to 8.9% of the general population.Callout Box 1 note 2

- Indigenous peoples are 2 times as likely to develop cardiovascular disease than non-Indigenous Canadians. Research also shows that First Nations and Inuit patients generally have heart attacks earlier in life.Callout Box 1 note 3

- For 14 of the 15 most common forms of cancer, First Nations have lower five-year survival rates than other populations in Canada.Callout Box 1 note 4

- The rate of tuberculosis is 50 times higher among Inuit and 5 times higher among First Nations than the national Canadian average.Callout Box 1 note 5

- In Canada, Indigenous people account for 5% of the populationCallout Box 1 note 6, yet 5-8% of reported HIV cases.Callout Box 1 note 7

Before colonization, many Indigenous women and girls held positions of leadership and decision-making in their respective populations, which were significantly harmed by forcible alteration of matrilineal practices and the denial of rights for Indigenous women under the Indian Act. The National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) notes that Indigenous women and girls are almost twice as likely to face violence than non-Indigenous women, with almost six in every ten Indigenous women and just over three in every ten non-Indigenous women having experienced physical assaultFootnote 34Footnote 35 Furthermore, it is imperative to consider the additional health services required for people with uteruses. Indigenous women and girls, those identifying as two spirit, women, gender fluid, or non-binary with uteruses have additional health needs which may include pregnancy and childbirth.

Finding #2: First Nations and Inuit in Canada experience a disproportionate level of medical challenges, including chronic illnesses and mental health and wellness conditions.

Interviewees noted particular medical conditions and challenges that are most prevalent amongst Indigenous populations, which includes the following:

Chronic Illnesses and Multi-Morbidities

Throughout interviews, partners discussed the medical conditions and illnesses that were most prevalent for First Nations and Inuit. The heightened incidence of chronic illness and multi-morbidities among Indigenous peoples is added to by literature.

Chronic Conditions

A significant number of First Nations respondents (33%) noted that obesity, cancer, diabetes, and other chronic illness continuously impacted the overall health and wellness of First Nations and Inuit. More specifically, several partners noted diabetes as a core health need, with statistics validating that Indigenous populations are diagnosed with diabetes earlier in life, with more severe symptoms at the time of diagnosis, and also experience higher rates of complications and worse treatment outcomes than non-Indigenous Canadians.Footnote 36 The increased prevalence of diabetes among First Nations and Inuit results in greater need for appropriate staff and equipment to support with preventative care and treatment, and education initiatives in Indigenous populations. Further, the symptoms of diabetes can increase the need for other specialists (i.e., for foot care treatment).

Self-reported rates of long-term chronic health conditions and their prevalence among Indigenous populations are outlined below:

| Self-Reported Health Issues | Proportion of General Population | Proportion of Indigenous Peoples (Statistics Canada, 2022) |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Term Health Problems | 44%

(16.8 million people)Footnote 37 |

57%

(568,940 people) |

| Asthma | 9.9%

(3.8 million people)Footnote 38 |

14.3%

(142,540 people) |

| Arthritis | 20%

(6 million people)Footnote 39 |

20.1%

(200,590 people) |

| High-Blood Pressure | 19.6%

(7.5 million people)Footnote 40 |

17.5%

(175,200 people) |

Communicable Diseases

A select number of interviewees (7%) noted sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and tuberculosis as additional core health issues experienced by First Nations and Inuit within their communities. In the case of tuberculosis, it was noted that the housing shortage and lack of capacity to support isolation of contagious patients results in increased numbers of the disease among First Nations and Inuit in their communities.

Mental Health and Wellness

Content Warning: This section may cause distress for some readers.

The number of Indigenous peoples impacted directly or indirectly by mental health and wellness challenges continues to grow.

Case Study #1

File Hills Qu'Appelle Tribal Council (FHQTC)

Region: SK | Program Focus: Health Planning; HSIF; eHealth

The All Nations Healing Hospital and FHQTC Health Services operates the Miko-Mahikan Red Wolf program (further described in Case Study #3) and began as a response to the rising prevalence of homelessness, addiction struggles, and overdose within the 11 Nations represented by the File Hills Qu'Appelle Tribal Council (FHQTC). Miko-Mahikan operates a harm-reduction program, addiction support, opioid replacement therapy, and education, awareness, and outreach programming to support patients. In part, some of the operations of the Hospital, including pharmacy, women's health and low risk birthing was supported by HSIF funding.

Trauma

Traumatic experiences and intergenerational trauma are linked to mental health challenges in First Nations and Inuit populations. Historically and to this day, Indigenous peoples have endured trauma from a number of sources, which include but are not limited to colonialism, residential schools, forcible removal of children from their families, racism and discrimination. In addition, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People, and the persistent impacts of residential schools are all examples provided by interviewees as traumatic events that continue to exacerbate mental health challenges for themselves and people in their communities. According to the Calgary-based Mental Health Literacy Organization, mental health challenges are also linked to substance use challenge and suicide.Footnote 41

Substance Use & Addiction

Interviewees noted particularly acute challenges with alcohol and drug dependencies faced by First Nations and Inuit throughout Canada. Socioeconomic factors, including poverty, homelessness, and lack of access to social services and education are known contributors to substance dependence and addiction struggles. Literature also notes the impact of substance use and addition on exacerbation of homelessness, poverty, and barriers to access to social services.Footnote 42

Suicide

Statistics illustrate that youth suicide rates are higher among Indigenous youth than non-Indigenous youth in Canada. Suicide rates for First Nations people are three times higher than that of non-Indigenous people at 24.3 deaths per 100,000 person-years at risk.Footnote 43 The rates of youth suicide among Inuit is nine times higher than that of non-Indigenous people, at 72.3 deaths per 100,000 person-years at risk.Footnote 44

Finding #3: First Nations and Inuit communities have limited access to appropriate community-based health resources, including facilities, equipment, programs, staff, and training.

As noted in Finding #1 and Finding #2, accessFootnote 45 to health care is a significant challenge faced by people in Indigenous communities.

Community-Based Care

Due to the rural and/or remote nature of many Indigenous communities, the nearest health care center for First Nations and Inuit is often not close to their home. The lack of community-based care can, therefore, be the difference between life and death when seeking treatment for health-related issues. This is even more difficult where ambulatory services or transport treatment is unavailable, or in some instances as shared by interviewees, provision of service is refused near reserve communities.

Regional Specific Needs

Interviewees and literature review also note the unique needs faced in urban, rural and remote, and Northern communities. In urban settings, Indigenous peoples often experience a lack of cultural sensitivity when interacting with health care workers, as well as an overall lack of healthcare capacity and funding for health care services. In rural, remote, and Northern communities, there are increased difficulties with recruiting and retaining health care staff. In Northern communities the unique climate can cause limited or obstructed access to community by road (where road access exists), creating interrelated challenges of recruiting and retaining health care staff, climate impacts can result in a higher probability of certain medical conditions (e.g., respiratory and cardiovascular illness)Footnote 46 manifesting as well as increase challenges in housing or health facility construction and maintenance.

In order to ensure timely access to care, it is vital that people in communities have adequate and suitable facilities within the community, with the functioning equipment to provide health services.

According to interviews, many communities lack the physical space to operate facilities that support the level of health service delivery required, with some noting that their only option was to operate health services in closets or church basements. It was noted that some communities continue to not have access to clean waterFootnote 47, a necessity for an appropriate health facility.Footnote 48 In one Focus Group, it was noted that over 80% of one region's health facilities inventory had not been renovated/repaired since 2000, highlighting the need for renovations and repairs to maintain adequate facilities in which to provide care. The outdated nature of many of these buildings create additional challenges when attempting to outfit facilities with the necessary technology to operate effectively in the current society.

Furthermore, it was highlighted in interviews that facilities are not always equipped to allow for traditional and cultural practices, either as a result of limited financial and resource capacity or actual barriers in the physical infrastructure of the buildings (i.e., Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) system for smudgingFootnote 49), which sometimes relates to adhering to codes and/or standards in building construction and/or operation. When considering the adequacy and suitability of community-based health facilities, it is important to consider what the specific needs of the patients in that area are, and in the case of Indigenous communities, access to traditional medicine is a core need. One of the key challenges Indigenous peoples have faced is erasure of their culture and traditions, and an imposition of assimilation to western practices. For health facilities to truly meet the needs of the Indigenous communities, they must reflect community needs and values.

Community-Based Health Care Workers

In order to provide adequate and timely care, community health facilities require an appropriate level of staff. Most interviewees (58%) noted that there is a shortage of health care workers and limited health care capacity in communities. Partners noted an acute need for additional community-based workers to deliver health services and emphasized in these discussions that there have been ongoing challenges with recruiting and retaining health care staff in communities. These challenges include a lack of funding to allocate to salaries and benefits, a lack of interest from staff in remaining in-community (due to working conditions), and a lack of housing capacity to provide shelter for external health care workers. The lack of accommodation for health care workers in Northern regions was specifically noted as a key issue in one focus group. Interviewees highlighted a need for early education opportunities to encourage and support Indigenous youth to pursue careers in healthcare to support sustainable measures to overcome these continuous staffing shortages.

Appropriate Training & Expertise for Community

Most interviewees (55%) noted a specific gap in having access to health care workers with appropriate expertise, training, and cultural sensitivity. A select number of SMEs who participated in interviews recounted the challenges in hiring nursing staff, and how in their absence, communities have worked to train paramedics to ensure that they have the basic capabilities to treat patients in community rather than sending them to the provincial health center. In addition, due to the lack of training provided, even when staff have the appropriate tools, they would likely not be able to use them. Program partners also noted that community health directors have voiced the need to improve skillsets to support Licensed Practical Nurses (LPN), including training for various fields, including therapy, registered massage therapy (RMT), acupuncture, reflexology, dental hygiene, and child and youth counselling. It was emphasized that while there is great need for frontline health care workers, such as nurses and doctors, there is also need for support workers, including nursing informatics and digital technicians, particularly as the demand for remote, digital health services grows. Due to the distance between provincial health facilities and communities, there is often a need for speciality doctors (e.g., oncologists, endocrinologists) in community that continuously remains unmet.

Further, the need, and current lack of, culturally trained health practitioners was a key trend in interviews. A significant number of First Nations Representatives (44%) and SMEs (50%) noted that racism and discrimination in the healthcare system remains an ongoing issue. Given this, as well as trauma endured in the healthcare system, First Nations and Inuit patients require services delivered by individuals trained in cultural humility. Ideally, community-based staff would be members of the Indigenous community and would therefore have the necessary understanding of cultural sensitivities. Moreover, First Nations and Inuit patients require health services professionals who practice two-eyed seeing when providing care, including the strengths of both culturally-specific medicine and western medicine.

Technological InfrastructureFootnote 50