Transition 2021 Minister Hajdu Indigenous Services Canada overview - Book 1

Table of contents

Part A

- Indigenous Peoples of Canada: An Overview

- Overview of Indigenous Services Canada

- ISC and CIRNA: Division of Responsibilities

- Profiles of Indigenous Services Canada Senior Executives

- Profiles of Shared Services Senior Executives

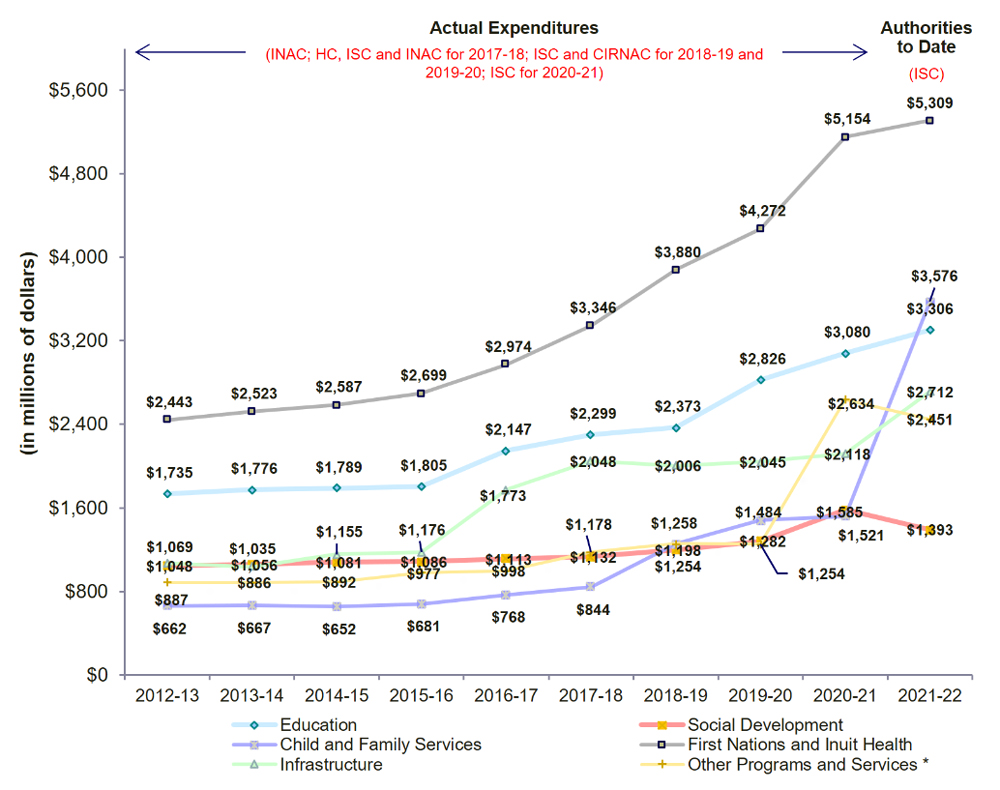

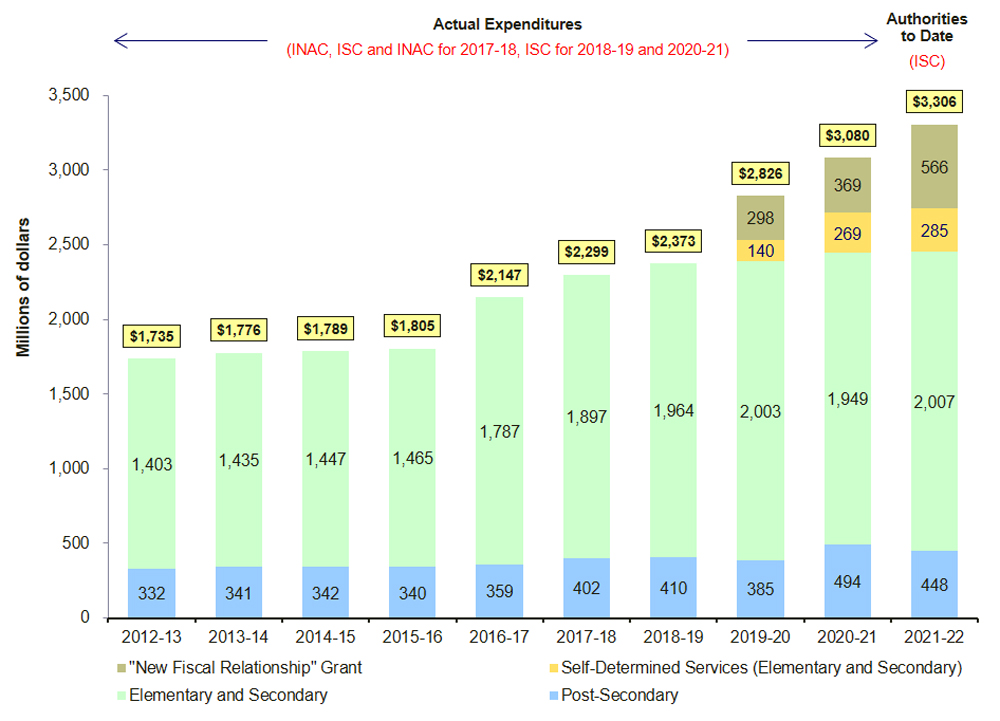

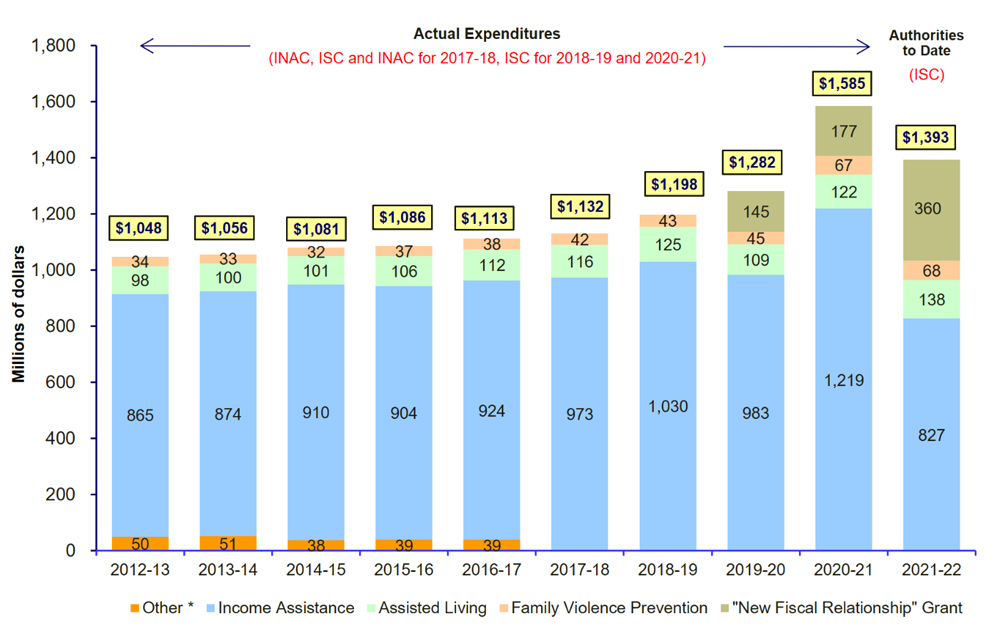

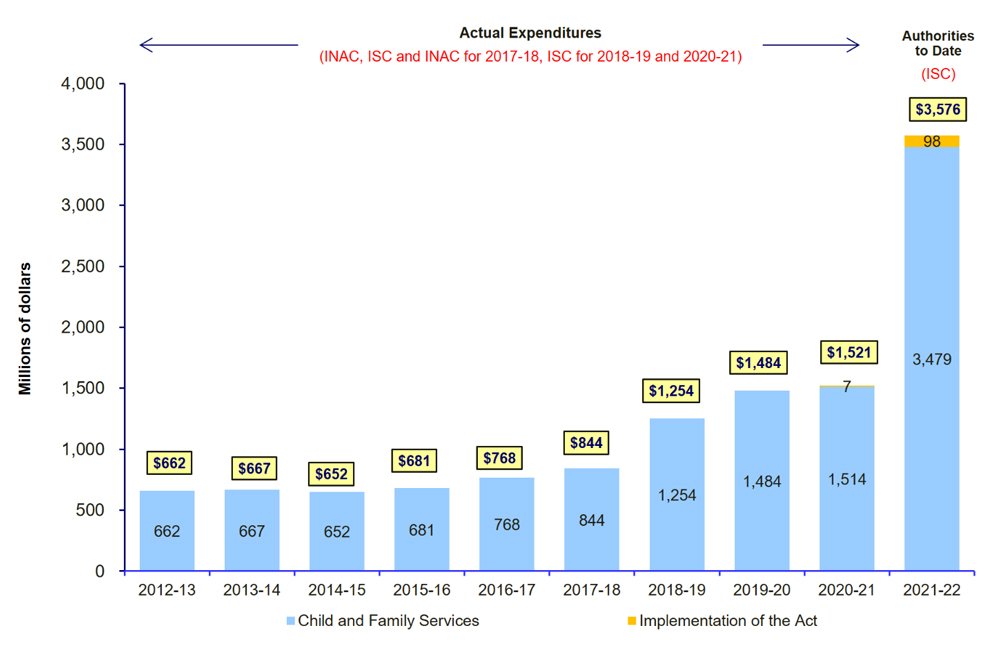

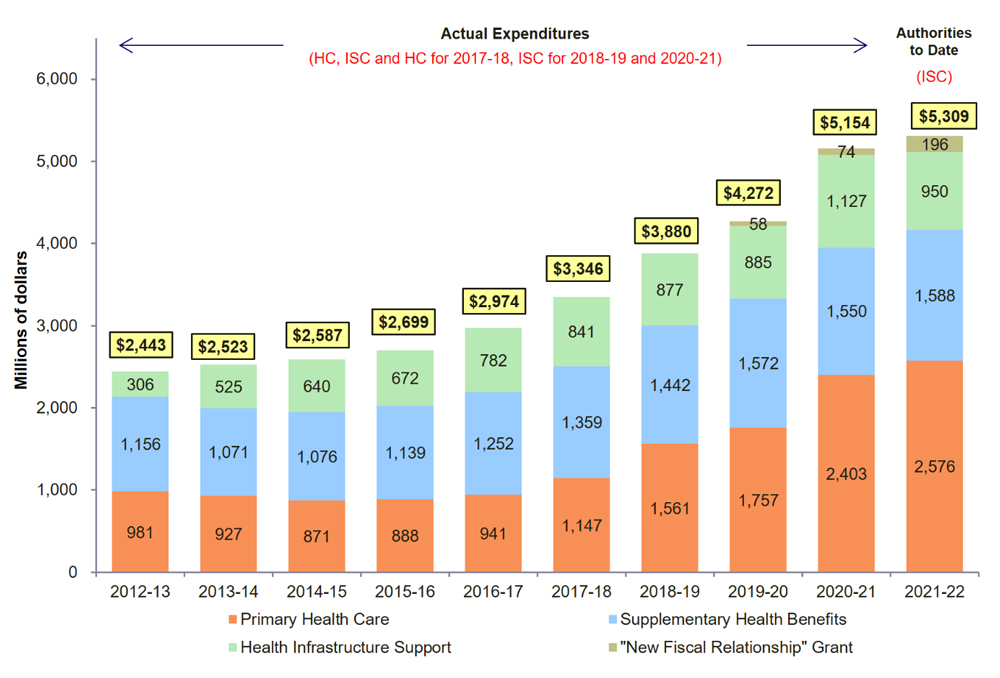

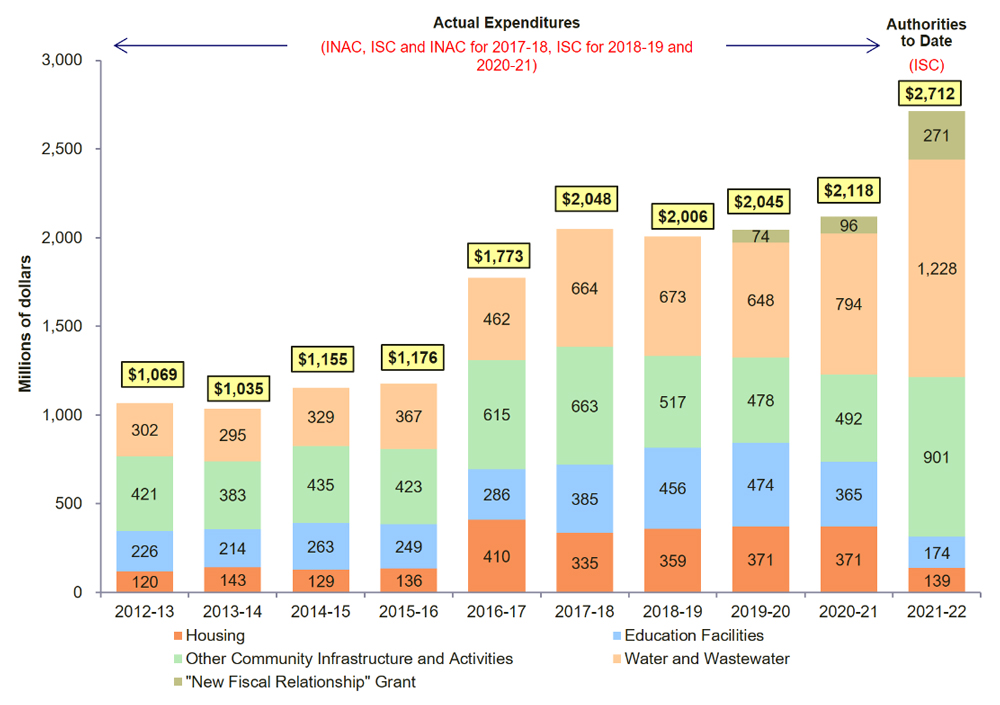

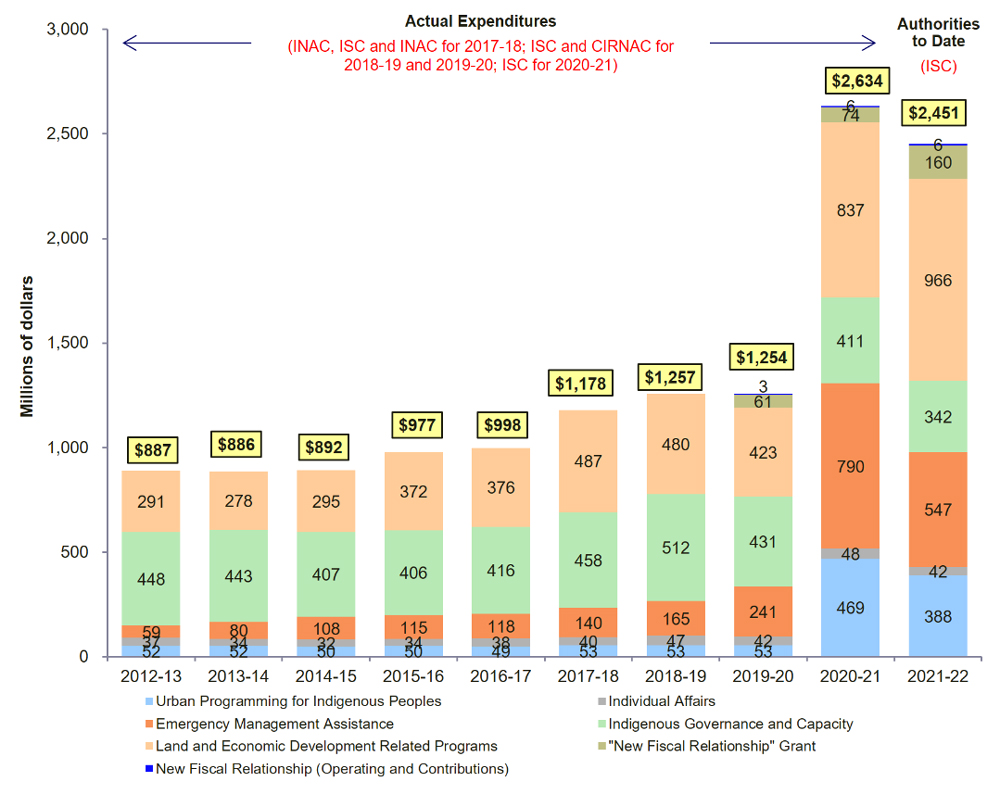

- Indigenous Services Canada Financial Overview

- COVID Response

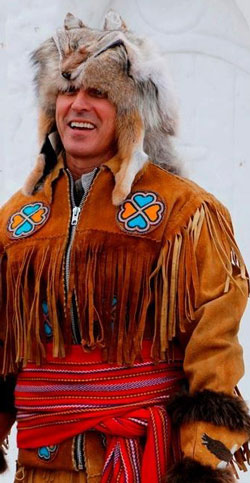

- Overview of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Cultural Protocols

Part B

Part A

1. Indigenous Peoples of Canada: An Overview

September 2021

Who are the Indigenous Peoples in Canada?

- 'Indigenous Peoples' is a collective name for the original inhabitants of North America and their descendants

- First Nations and Inuit: ancestors pre-date the arrival of Europeans

- Métis Nation: emerged as distinct, mixed-ancestry people from interactions between Europeans and First Nations (primarily in Ontario westward)

- First Nations, Inuit and Métis have some shared experiences, but all have unique cultures and identities

- Indigenous identities are highly diverse even within these three groups – each Indigenous nation and community has its own customs and traditions

- More than 70 Indigenous languages reported in the 2016 Census (see Annex A)

Indigenous Populations in Canada

- The overall Indigenous population (1,673,780) represent 4.9% of the Canadian population (34,460,065).

- Past censuses have emphasized two key characteristics of the Indigenous population: that Indigenous Peoples are both young in age and growing in number. Since 2006, the Indigenous population has grown by 42.7%— more than four times the growth rate of the non-Indigenous population.

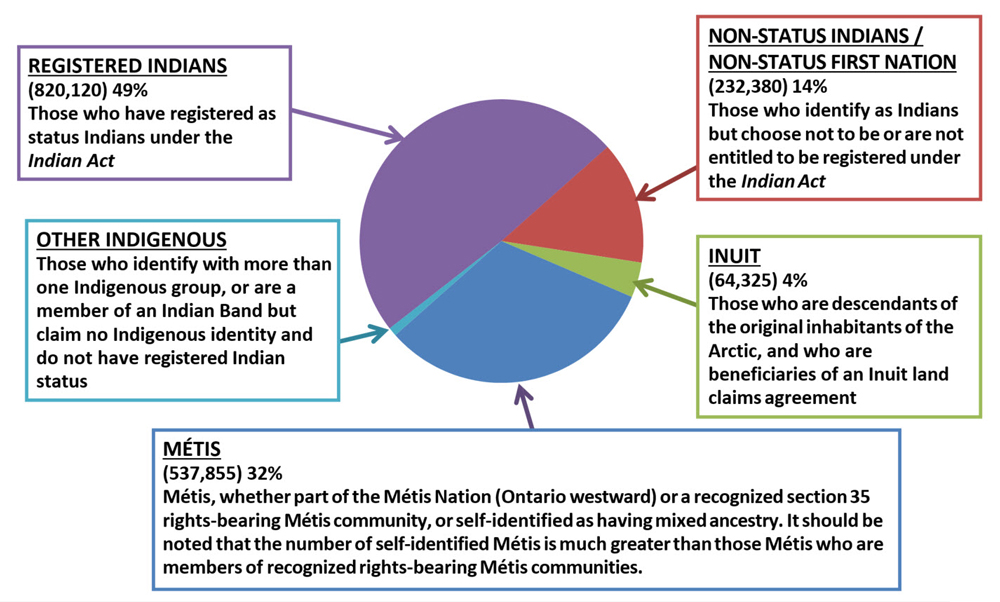

Text alternative for Indigenous Populations in Canada

- Registered Indians (820,120) 49%

Those who have registered as status Indians under the Indian Act - Non-status Indians / Non-status First Nation (232,380) 14%

Those who identify as Indians but choose not to be or are not entitled to be registered under the Indian Act - Inuit (64,325) 4%

Those who are descendants of the original inhabitants of the Arctic, and who are beneficiaries of an Inuit land claims agreement - Métis (537,855) 32%

Métis, whether part of the Métis Nation (Ontario westward) or a recognized section 35 rights-bearing Métis community, or self-identified as having mixed ancestry. It should be noted that the number of self-identified Métis is much greater than those Métis who are members of recognized rights-bearing Métis communities. - Other Indigenous

Those who identify with more than one Indigenous group, or are a member of an Indian Band but claim no Indigenous identity and do not have registered Indian status

History of Indigenous Policy in Canada

Early Contacts

- First Nations people and Inuit lived in what is present day Canada at time of contact

- Encountered settlers from 1534 to the early 1900s

- Engaged in trade, military alliances and Peace and Friendship Treaties

- Unions between First Nations women and settlers created a distinct Métis culture

Colonial and Canadian Era

- Royal Proclamation, 1763: British Crown acknowledged Indigenous rights to lands, established protocols for treaty-making and formalized the Crown-Indigenous relationship. A series of land surrender treaties were concluded in what is now Southern Ontario.

- After being considered military allies, Indigenous peoples were increasingly viewed as a detriment to the proper development of the colonies

- Policies of Civilization 1820s: new policies are put in place to create reserve lands for First Nations while encouraging Indigenous communities to abandon traditional ways of life for ones more similar to that of British settlers.

- Education and lands 1840s and 1850s: increased efforts are placed on establishing schools for Indigenous children and the imposition of settler concepts of land ownership

- British North America Act, 1867: section 91(24) assigns federal jurisdiction over "Indians, and lands reserved for the Indians".

- Numbered Treaties, 1871-1921: 11 numbered treaties signed in Ontario, Manitoba, British Columbia, Alberta, Yukon and Northwest Territories for respectful co-existence, some treaties included socio-economic provisions, such as a medicine chest, schools or economic means (e.g. "cows and plows").

- Indian Act, established in 1876, as a means of assimilation, which led to direct control of communities and reserves, imposition of education systems, controlled movement of Indians through pass system, gender discrimination against women who married non-Indigenous men and loss of status via enfranchisement.

- Paternalism 1880s-1950s: despite the creation of wide-ranging social, health care and education programs, the core activities of the Department focus on efforts to control Indigenous Peoples such as through residential schools and forced relocations

- Bryce Report, 1907: Chief Medical Health Officer, Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce, submitted a report to the Department, revealing that overcrowding and unsanitary living conditions in residential schools were spreading disease and that students were dying from it. Deputy superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott disregarded the report and prevented it from being officially published.

- Federal proposals to transfer on-reserve service delivery to provinces resulted in only the Canada-Ontario 1965 Indian Welfare Agreement.

Activism and Rights Assertions

- 1940s: in the post-war period, regional Indigenous organizations are formed to advocate for changes to policies and improvements to the deteriorating state of Indigenous communities.

- 1969: White Paper – federal policy statement intended to repeal the Indian Act and assimilate Indigenous Peoples into broader Canadian society; Indigenous Peoples responded with Red Paper for recognition of Indigenous Peoples and their treaty rights.

- 1971: National Indian Brotherhood, later Assembly of First Nations (AFN), provides Canada-wide representation of Indigenous Peoples. Also, 1971 marks the creation of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), the primary organization representing Inuit in Canada, out of concerns of Inuit leaders regarding land and resource ownership in Inuit Nunangat.

- 1983: Creation of the Métis National Council (MNC), the organization representing the Métis Nation nationally and internationally.

Recognition

- Modern Treaties 1873: the Calder decision of 1973 pushes the Government of Canada to recognize outstanding Indigenous rights over lands and the adoption of the comprehensive land claims process to negotiate new treaties with Indigenous communities.

- Section 35 of Constitution Act, 1982, recognizes and affirms Aboriginal and treaty rights of Indigenous Peoples (defined as First Nations, or "Indians," Inuit and Métis).

- Indigenous Peoples advocated for their recognition during attempted Meech Lake Accord, 1990 and Charlottetown Accord, 1992.

- 1991-1996: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples made 350 recommendations, including the enactment of legislation and creation of institutions that would provide the authority for Indigenous Peoples' self -determination.

Devolution and Community-based Services

- Over the years, colonial policies have existed that contributed to the disempowerment of Indigenous Peoples. However, progress has been made to recognize and implement Indigenous rights and self -determination.

- Indigenous Control 1970s-1980s: federal programs and policies are changed to allow for increased local control by community governments, starting with schools and education services in the 1970s and later for band governance in the 1980s.

- Indian Health Policy, 1979: development of a new policy approach to First Nation health-care that focuses on a more inclusive and community led services.

- Cree Naskapi Act, 1984 and Sechelt Indian Band Self-Government Act, 1986: first agreements to pull First Nations outside of Indian Act to create self-government.

- Inherent Right Policy, 1995: establishment of a negotiated process to establish self -government agreements resulted in 22 agreements across 43 communities, and is a central component to Modern Treaties.

- First Nations Land Management Act, 1999: creation of a regime for First Nations to opt-out of 40 Indian Act provisions on land, environment and resources, to develop their own land and resources management codes. Similar regimes established in a range of areas, including fiscal management, First Nations elections, commercial development, and oil and gas management.

- Self-determination through federalism:

- 1999: Territory of Nunavut created; and

- 2014: Northwest Territories became the second territory to take over land and resources responsibilities, as the final major step in the territory's devolution process.

Modernizing Services

- 2015: the Truth and Reconciliation Commission examining the impacts of Residential Schools issues 94 Calls to Action to guide the reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

- 2017: announcement of the dissolution of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and creation of two new departments: Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC).

- 2017: First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) joins ISC after 70 years of operation under Health Canada.

- ISC is committed to supporting and empowering Indigenous control over delivery of services and improving socio - economic conditions and quality of life in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities; key to Indigenous self - determination.

- 2019:

- A legislative mandate for ISC to work towards the transfer of departmental responsibilities and collaborate with Indigenous partners in all aspects of service delivery.

- The Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families became an official law, and on January 1, 2020, its provisions came into force.

- The Indigenous Languages Act which is intended to support the reclamation, revitalization, maintaining and strengthening of Indigenous languages received Royal Assent.

- 2020-21: COVID response sees unprecedented investments in programs and services to support Indigenous communities and businesses through the pandemic and strengthened partnership with Indigenous leadership.

- 2021:

- Federal Pathway to Address Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ People is launched.

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act received Royal Assent.

Demographic Trends

- In 2016, 1,673,785 people self-identified as an Indigenous Person in Canada, accounting for 4.9% of the total population

- This is a 42.7% increase from 2006 – a rate more than 4 times greater than non-Indigenous population – making Indigenous Peoples the fastest growing population in Canada

- Between 2006 and 2016:

- Registered Indian population grew by 31.5% to 820,120 people

- Non-Status First Nation population grew by 74.5% to 232,380 people

- Métis population grew by 51.3% to 537,855 people*

- Inuit population grew by 31.0% to 64,330 people

- As of 2016, 4 in 10 registered Indians live on-reserve (331,030)

- Increase from 2011 when 315,995 registered Indians lived on-reserve

- 44,620 residents of reserves were not Registered Indians

- This population is also the focus the majority of ISC spending

- 57.9% of Indigenous Peoples reported living in off-reserve population centres in 2016

- Indigenous Peoples are the youngest population in Canada

- About 44% were under age 25 in 2016, compared to 28% for non-Indigenous people

- By 2036, the Indigenous population is projected to number between 2.0 and 2.6 million, which will represent between 4.6% and 6.1% of the Canadian population.

*The growth in the Métis and Non-Status First Nation populations are not solely due to natural growth but rather an increase in the number of individuals self-identifying as Métis or Non-Status First Nation.

Current Gaps and Challenges

HEALTH AND SOCIAL

- First Nations and Inuit populations are affected by major health issues, including lower life expectancy, higher rates of chronic illnesses (e.g., diabetes) and communicable diseases (e.g., tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS), higher infant mortality rates and higher suicide rates, relative to the broader Canadian population.

- The three-year rate of tuberculosis from 2016 to 2018 was 0.5 cases per 100,000 population for the non-Indigenous Canadian-born population. This compares to:

- First Nations with status living on-reserve: 24.3 cases per 100,000

- Inuit in Inuit Nunangat: 211 cases per 100,000

- The infant mortality rate for the non-Indigenous population in Canada was 4.4 per 1,000 singleton births. This compares to:

- First Nations: 9.2 per 1,000 singleton births (2.1 times higher)

- Inuit: 12.3 per 1,000 singleton births (2.8 times higher)

- Métis: 10.5 per 1,000 singleton births (2.4 times higher)

- The projected life expectancy at birth for the non-Indigenous population in Canada was 81.4 years for males and 87.3 for females. This compares to:

- First Nations: 72.5 for males and 77.7 for females

- Inuit: 70.0 for males and 76.1 for females

- Métis: 76.9 for males and 82.3 for females

- Gaps in basic living conditions (e.g., housing, water) also have significant impacts on long-term health status improvements.

- First Nations and Inuit people also face many of the same emerging health priorities as other Canadians (e.g., aging, mental health), but often with more acute consequences due to their poorer access to immediate and preventative health services.

- Indigenous children currently represent 52.2% of children in foster care while accounting for only 7.7% of the overall population of children under 15.

HOUSING

6.0% of the non-Indigenous population lived in a dwelling in need of major repairs in 2016. This compares to:

- Registered Indian on-reserve: 40.0%

- Registered Indian off-reserve: 12.2%

- Non-Status Indian: 12.3%

- Inuit: 21.8%

- Métis: 10.3%

The proportion of non-Indigenous dwellings classified as crowded was 1.8% in 2016. This compares to:

- Registered Indian on-reserve: 12.7%

- Registered Indian off-reserve: 2.7%

- Non-Status Indian: 1.1%

- Inuit: 16.0%

- Métis: 0.8%

Homelessness

- 30% of homeless 19,536 respondents across 61 communities in Canada identified as an Indigenous Person, with the majority identifying as First Nations

EDUCATION

There remain persistent gaps in educational attainment among 25 to 64 year olds. The non-Indigenous population with high school education or higher was 89.2% in 2016. This compares to:

- Registered Indian on-reserve: 57.0%

- Registered Indian off-reserve: 75%

- Non-Status Indian: 80.3%

- Inuit: 55.9%

- Métis: 82.3%

The proportion of non-Indigenous Peoples with university (Bachelor or higher) education increased from 20.1% in 2001 to 29.3% in 2016. This compares to:

- Registered Indian on-reserve: 3.4% in 2001 and 5.4% in 2016.

- Registered Indian-off reserve: 6.8% in 2001 and 11.3% in 2016.

- Non-Status Indian: 7.0% in 2001 and 11.9% in 2016.

- Inuit: Inuit with university-level education was 2.5% in 2001 and 5.3% in 2016.

- Métis: Métis with university-level education was 7.0% in 2001 and 13.6% in 2016.

- Although persistent, the gap in educational attainment between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations is shrinking particularly amongst the Inuit and Métis where the proportion of those with a university education nearly doubled from 2001 to 2016.

- In 2019, ISC introduced a new funding formula that ensures that base funding provided for Education is comparable to provincial systems across the country.

EMPLOYMENT

Employment rates were 62% in 2001 and 60.5% in 2016 for Canada's non-Indigenous population. This compares to:

- First Nations: Employment rate for Registered Indians on reserve decreased slightly from 37% in 2001 to 36.3% in 2016.

- Registered Indians off-reserve: the employment rate increased from 48% in 2001 to 50.7% in 2016.

- Non-Status Indians: the employment rate increased slightly from 56% in 2001 to 56.5% in 2016.

- Inuit: Employment rate for Inuit remained stable between 49% in 2001 to 48.9% in 2016

- Métis: Employment rate for Métis increased slightly from 60% in 2001 to 60.5% in 2016.

INCOME

Substantial gaps in median employment income persist between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples. The median income of the non-Indigenous population in 2015 was $34,013. This compares to:

- Registered Indian on-reserve: $17,251

- Registered Indian off-reserve: $26,304

- Non-Status Indian: $26,525

- Inuit: $20,939

- Métis: $31,675

INTERGENERATIONAL IMPACTS

- Residential Schools: An estimated 150,000 Indigenous children were removed and separated from their families and communities to attend residential schools between 1831 and 1996.

- Relocation and Displacement: The forced relocation of Inuit families to the High Arctic in the 1950s to exert Canadian sovereignty in the North resulted in dislocation and starvation. Inuit families were broken up as loved ones were sent to southern Canada for medical treatment during the tuberculosis epidemic, which lasted from the 1940s to the 1960s, many never to return.

- Sixties Scoop: Over 11,000 First Nations children* were taken from their home and families and placed in foster care, and eventually adopted out to non-Indigenous families across Canada and the United States.

- Unmarked burials: Several unmarked burial sites have been located near former residential schools across Canada in the last year acting as a stark reminder of past injustices and a call to action to fulfill the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Actions, particularly 71-76.

Key Reconciliation Milestones

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1991-1996

- 350 recommendations

- Recognition and implementation of the right to self-determination, as well as enactment of legislation to create new laws and institutions to provide authority and tools for Indigenous peoples to structure their own political, social and economic future

- Gathering Strength, Canada's response to the report is released in 1997

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- Initiated by 2006 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement and 2008 statement of apology, combined with findings of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples led to the launch of a national Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- Final report was released in 2015 with 94 Calls to Action to:

- renew the relationship and decolonize institutions

- close socio-economic gaps and foster healing

- engage and educate Canadians

- Canada's response being advanced through various initiatives (e.g., Indigenous Languages Act, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act Legislation, amending the Oath to Citizenship, establishing National Day for Truth and Reconciliation as an official federal statutory holiday to be marked annually on September 30, 2021, etc.)

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

- High rates of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls caused the Government of Canada to launch a national inquiry in 2016, independent from the federal government

- Final report was released in 2019 with 231 Calls to Justice

- Federal Pathway to Address Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual People is launched in June 2021

Examples of Progress Towards Self-Determination

Education Transformation Regional Education Agreements

• Establishment of unique education agreements that were/are supported by a combination of the participating First Nations' core K-12 education funding and proposal-based funding:

- The Tripartite Education Framework Agreement in British Columbia (2012-2017)

- The Manitoba First Nations School System in Manitoba (2017)

- The Maskwacis Education Services Commission in Alberta (2018)

- Kee Tas Kee Now Tribal Education Authority in Alberta (2019)

- Athabasca Denesuline Education Authority in Saskatchewan (2019)

- Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation Education Authority in Saskatchewan (2020)

- Whitecap Dakota Tripartite Regional Education Agreement in Saskatchewan (2020)

- Elsipogtog First Nation Education Authority in New Brunswick (2021)

- Treaty Education Alliance in Saskatchewan (2021)

Child and Family Services

- An Act Respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis Children, Youth and Families, 2019

- First co-developed legislation between the Government of Canada and First Nations, Inuit and Métis representatives to reform Indigenous Child and Family Services

- Affirms the rights of First Nations, Inuit and Métis to exercise jurisdiction over Child and Family Services to keep families together and reduce the number of Indigenous children in foster care

- As of August 2021, over 100 Indigenous groups and communities had started to develop Indigenous Child and Family Services policies, models and laws based on their particular histories, cultures, and circumstances. Some 73 proposals and more than $30 million in funding to build capacity has been approved for communities in preparation for exercising jurisdiction over Child and Family Services.

- Progress has been made towards having Indigenous Child and Family Services laws receive force of law as federal law through tripartite coordination agreements under the Act, with 17 coordination agreement discussions ongoing, one completed with Cowessess First Nation, and about 20 discussions expected to begin annually over the next few years.

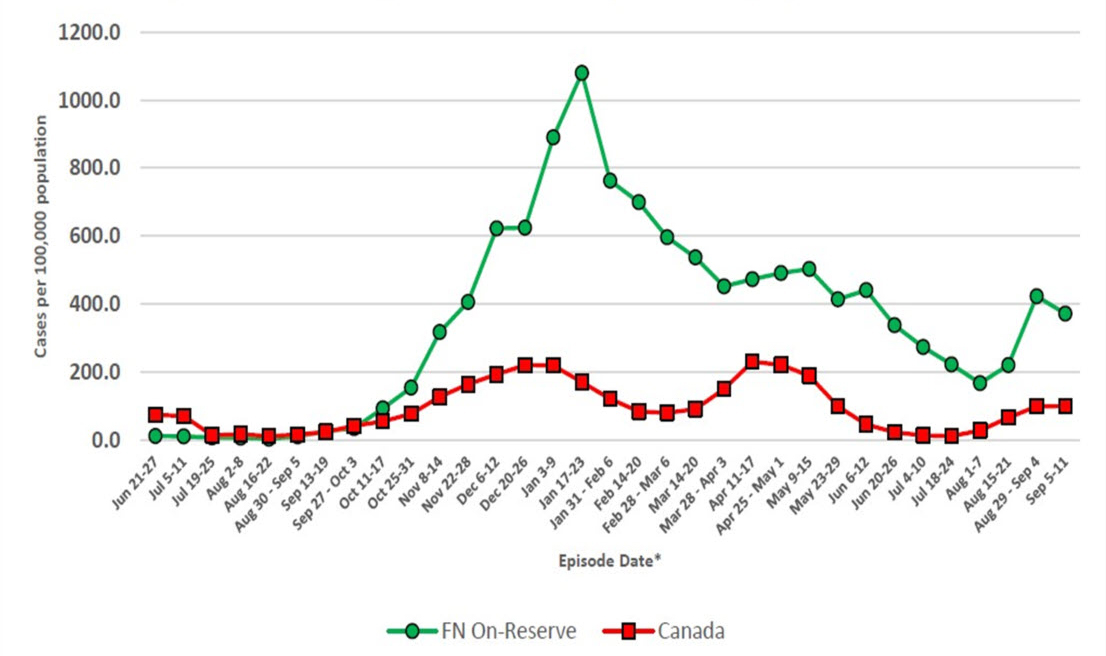

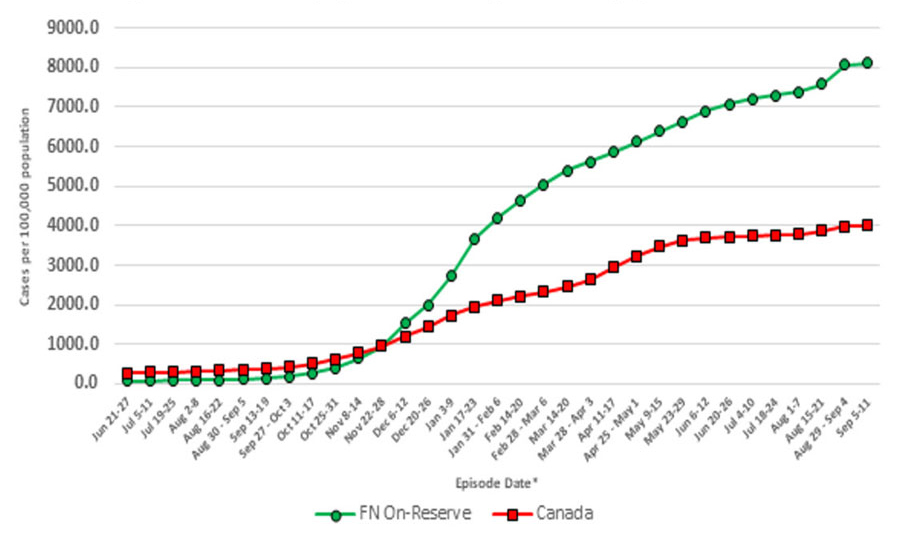

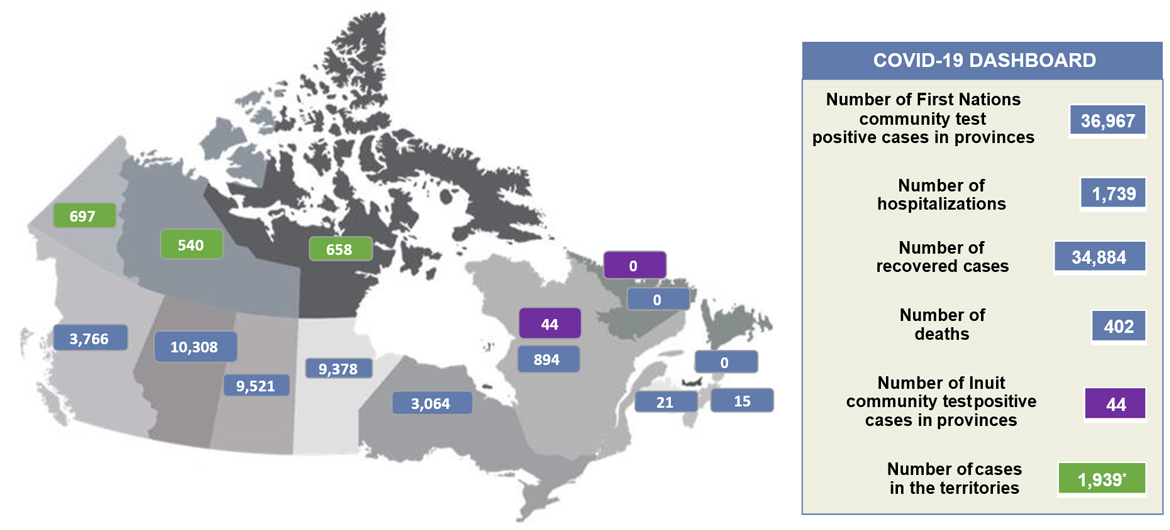

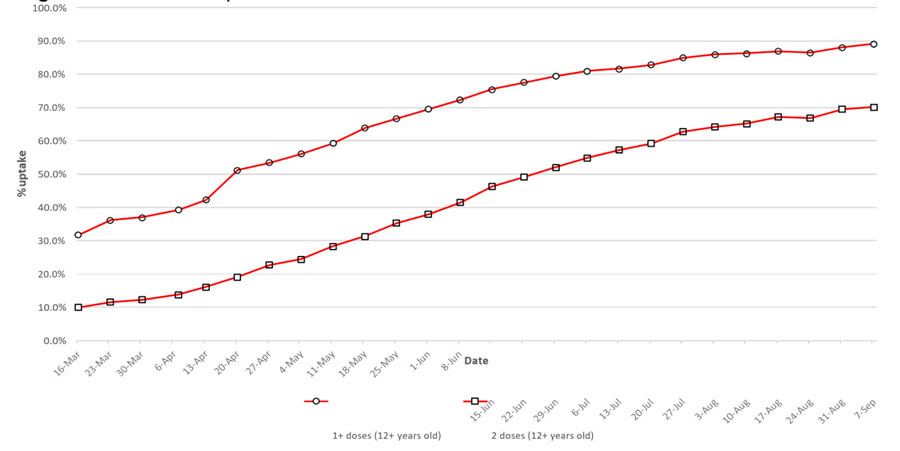

COVID-19 Response

- Over the course of 2020 and 2021, Canada worked closely with Indigenous partners to support community-led responses to COVID-19 through existing ISC programming, significant new investments in public health, and a variety of financial supports to mitigate the economic impacts of the pandemic.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act

- The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act received Royal Assent in June 21, 2021, and immediately came into force.

- The legislation advances the implementation of the Declaration as a key step in renewing the Government of Canada's relationship with Indigenous Peoples and provides a framework for reconciliation, healing and peace, as well as harmonious and cooperative relations based on the principles of justice, democracy, respect for human rights, non-discrimination and good faith.

Fiscal Management

- First Nations Fiscal Management Act, 2006, provides First Nations with support and tools to strengthen local economies.

- Established key institutions – the First Nations Financial Management Board (FNFMB), the First Nations Finance Authority (FNFA) and the First Nations Tax Commission (FNTC).

Modern Treaties and Land Claims

- Treaties define rights, benefits and obligations for the signatories. Modern treaties can cover land ownership, financial settlements, self-government, and resource revenue sharing.

- The James Bay and Northern Quebec Cree Agreement was the first modern treaty. Canada has since signed 25 additional treaties with Indigenous groups, including modern land claims with the four Inuit regions.

- Modern treaties form the basis of Canada's relationship with 97 Indigenous communities (representing about 89,000 Indigenous Peoples). These agreements provide holders certainty on land rights for around 40% of Canada's land mass.

First Nations Land Management

- Since 1999, First Nations can opt-out of 44 sections of the Indian Act on land management and develop their own laws about land use, environment and natural resources, pursuant to the First Nations Land Management Act (FNLMA).

- There are currently 99 First Nations that are managing their lands pursuant to the First Nations Land Management Act, with an additional 62 in the process of developing their land codes.

- Similar opt-in legislations to the First Nations Land Management Act have been created to increase First Nations control over elections, oil and gas management as well as commercial development.

Self-Government Agreements with Métis Nation in Ontario, Alberta and Saskatchewan

- First self-government agreements signed with the Métis governments in 2019.

- Agreements recognize Métis jurisdiction in core governance areas, including citizenship, leadership and land development.

Some Current Indigenous Priorities

First Nations

- Climate change

- Recovery post-pandemic

- Nation re-building and rights recognition

- New fiscal relationship

- Child & Family Services and Jordan's Principle*

- Sixties Scoop claims process

- Implementation of United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada's 94 Calls to Action plus Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls National Inquiry's 231 Calls to Justice

- Trauma-informed mental health and cultural supports

- Policing and community safety

- Infrastructure (access to clean water, emergency management, etc.)

Inuit

- Inuit-Crown land claims

- Inuit Nunangat policy space

- Recovery post-pandemic

- Inuktut revitalization, maintenance, and promotion

- Reconciliation measures

- Education, early learning, and training

- Health and wellness (COVID-19 relief, tuberculosis elimination, Inuit-led suicide prevention, etc.)

- Environment and climate change

- Housing and infrastructure

- Economic development and procurement

- Legislative priorities

- Food security

- Implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act

Métis Nation

- Governance

- Recognition

- Reconciliation

- Recovery post-pandemic

- Improving socio-economic conditions

- Implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act

- Implementation of the Supreme Court's Daniels decision

*Jordan's Principle is a child-first principle that is a legal obligation of Canada to address the unmet needs of First Nations children in health, social and education, no matter where they live in Canada.

*Information based on Assembly of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Native Women's Association of Canada and Congress of Aboriginal Peoples election priorities, and existing Métis National Council statements.

Recent Trends

Self-determination and service transfer*

- There has been an acceleration of the movement to increase Indigenous control over services delivered to Indigenous citizens. The COVID-19 response has provided some important lessons that will inform the transfer of services (e.g., capacity of Indigenous leadership to response to crisis situations and meet the needs of their members). In addition, Tripartite Emergency Management Agreements are an instrumental mechanism used for priority setting and planning in response to other emergencies, such as severe wildfires.

- Legislation asserting First Nations' jurisdiction over Child and Family Services, to ensure that First Nations can control how these critical services are delivered. Policy work to transfer program responsibilities through initiatives such as the Atlantic First Nations Water Authority.

- Over 115 First Nations now benefitting from 10-year grants, providing fiscal flexibility for First Nations leadership to operate outside the restrictive parameters of contribution agreements to manage their funds.

*Work ongoing to clarify the differences and interplay between service transfer agreements under section 9 of the Department of Indigenous Services Act and agreements under section 35 of the Constitution.

Litigation Management

- Supreme Court decisions such as Daniels (2016) expanded the meaning of Indians in the constitution to include Métis and non-status people.

- Since 2016, Canadian Human Rights Tribunal orders have instructed Canada to stop discriminatory practices in the delivery of health and social services to First Nations children (Jordan's Principle and Child and Family Services) and have issued a series of remedial orders that have expanded the definition of a First Nations child for the purposes of eligibility under Jordan's Principle.

- Class action litigation is on the rise in the context of services delivered by the federal government to Indigenous Peoples. Canada recently reached an Agreement-in-Principles to resolve a class action litigation related to safe drinking water in First Nation communities.

Reconciliation

- Addressing the legacy of residential schools, particularly around the issue of the continued identification of unmarked burials.

- Addressing systemic racism particularly in health and justice.

2. Overview of Indigenous Services Canada

Role of the Minister of Indigenous Services

"The Minister is to ensure that: child and family services; education; health; social development; economic development; housing; infrastructure; emergency management; and governance services are provided to eligible Indigenous individuals, communities and governing bodies." (Department of Indigenous Services Act, s.6 (2))

The Minister is to "provide Indigenous organizations with an opportunity to collaborate in the development, provision, assessment and improvement of the services" and is to "take the appropriate measure to give effect to the gradual transfer to Indigenous organizations of departmental responsibilities". (Department of Indigenous Services Act, s.7(a-b))

The Minister must cause to be tabled in each House of Parliament, within three months after the end of the fiscal year (…) a report on:

- the socio-economic gaps between First Nations, Inuit, Métis individuals, and other Canadians and the measures taken by the Department to reduce those gaps; and

- the progress made towards the transfer of responsibilities."

(Department of Indigenous Services Act, s.15)

Overview of Services

Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) provides programs and services to First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples, which focus on:

- keeping children and families together,

- supporting quality education,

- improving health outcomes,

- building reliable infrastructure, and

- enabling economic prosperity.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis covered by self-government agreements receive services directly from their Indigenous government. These relationships fall mainly under the mandate of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis

- ISC also supports a wide range of Indigenous governments and institutions who serve and represent First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

- First Nations, Inuit and Métis students can also receive support for post-secondary education support.

- Urban Programming for Indigenous Peoples is delivered through not-for-profit urban Indigenous service delivery organizations (i.e., Friendship Centres, Inuit and Métis organizations) and non-Indigenous organizations, including municipal governments, health and education authorities and institutions that have demonstrated support from Indigenous organizations or Indigenous community groups.

Common to First Nations and Inuit

- First Nations and Inuit communities have access to a range of services that are supplementary to those provided by the provinces and territories, including mental health and substance use services, public health services, home, community, and palliative care.

- Some services are available to First Nation individuals and Inuit regardless of residency (e.g., non-insured health benefits, access to health, social, and educational services for children through Jordan's Principle and the Inuit Child First Initiative, and post-secondary education funding).

- Inuit have self-government agreements and governance structures that allow for greater community control.

- ISC funds communities, service delivery organizations and, in some instances, delivers the services directly (e.g., nursing).

On-reserve First Nations

- ISC is involved in a wide range of services for on-reserve First Nations, similar to a province/territory or municipalities. This includes health, social, education, economic development, governance, and infrastructure services.

- In these cases, ISC's main role is one of funder, via contribution agreements, to First Nation governments and organizations who manage service delivery.

- The New Fiscal Relationship provides stabilized long-term funding to over 117 First Nations through the 10-year grant funding mechanism. This initiative aims to provide eligible First Nations, who choose to join the grant, with program supports to build capacity, do effective planning, and account for inflation and population increases on-reserve.

- The main services supported by the Department on-reserve include status registration, estates, primary care nursing, public health nurses and environmental public health, elementary and secondary education, post-secondary education, income assistance, assisted living, infrastructure such as housing, water and waste water, and education and health facilities among others.

Responding to COVID-19

- Recognizing that many Indigenous communities face unique challenges in addressing COVID-19, ISC has provided funding to help First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities, as well as urban Indigenous service delivery organizations to manage the pandemic, and to recover from the impacts of the pandemic.

- To support First Nations communities' efforts to mitigate and manage COVID-19 outbreaks on-reserve, ISC provided additional supports, including:

- COVID-19 swab sample testing;

- personal protective equipment, such as hand sanitizer, N95 masks, isolation shields, and gloves;

- deployed nurses, paramedics and provided air transportation for health human resources;

- provided funding for mobile structures, hotel or space rentals;

- provided logistics support identifying community spaces that can be upgraded or retooled; operational spaces for site servicing projects; and

- rolling out vaccination.

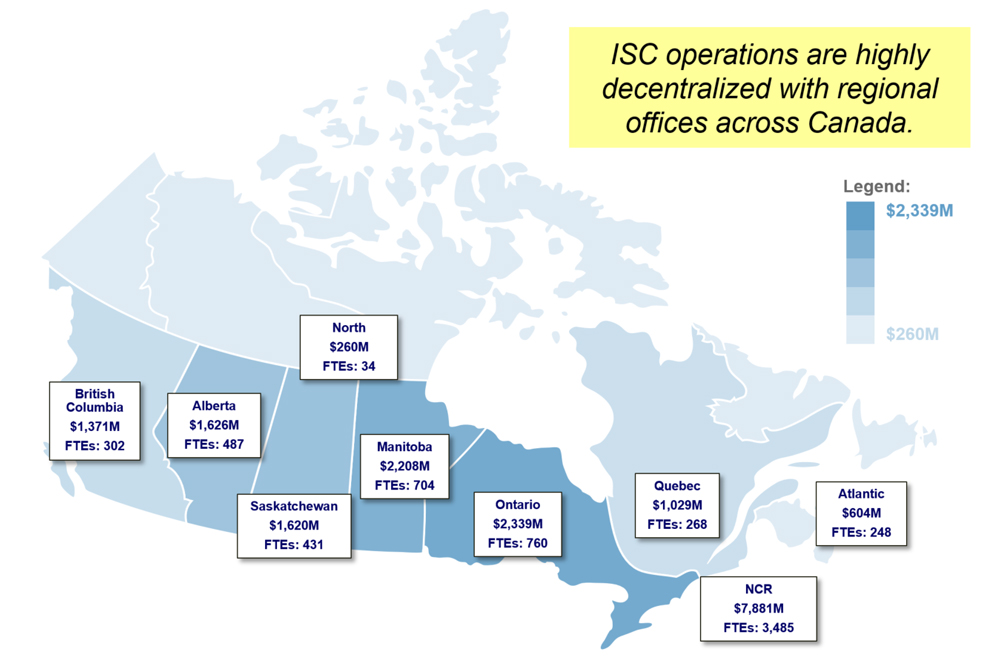

A National Footprint

National Capital Region

- The National Capital Region (NCR) office of Indigenous Services Canada plays an important role in defining the general policy direction of the department.

- It also maintains relationships with Indigenous organizations located in the National Capital Region, including the Assembly of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the Métis National Council, the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, and the Native Women's Association of Canada.

Regional Offices

- The regional offices of ISC are the face of the Department in direct work with Indigenous communities.

- Located in all continental provinces, the Atlantic region, and in some northern regions (Northwest Territories and Yukon), they maintain day-to-day relationships with a wide web of Indigenous organizations and governments at the local and regional levels.

- ISC offices are also responsible to ensure that programs are appropriately implemented.

Legislative Environment

Constitution Act, 1982

- Section 91(24) provides the Government of Canada with jurisdiction over "Indians and lands reserved for Indians".

- Section 35 recognizes and affirms "Aboriginal and treaty rights".

Department of Indigenous Services Act

- Came into force in July 2019.

- Outlines the powers, duties and functions of the Minister of Indigenous Services. It directs the Minister to ensure programs and services are delivered to eligible Indigenous individuals and emphasizes the objectives of closing socio-economic gaps between Indigenous Peoples and other Canadians, and of building capacity of Indigenous communities to support self-determination.

- The legislation notably includes:

- the different types of services provided to eligible Indigenous individuals (i.e., child and family services; education; health; social development; economic development; housing; infrastructure; emergency management; and governance);

- responsibilities to ensure that Indigenous organizations can collaborate in the development, provision, assessment and improvement of services.

- a ministerial power to enter into agreements with Indigenous organizations to transfer departmental responsibilities.

Indian Act

- Regulates the relationship between Canada and First Nations in a wide range of areas.

- For the purposes of this Act, the Minister of Indigenous Services is the Superintendent General of Indian affairs.

Legislation for which the Minister of Indigenous Services is responsible:

- An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families

- Indian Act Amendment and Replacement Act

- First Nations Elections Act

- Indian Oil and Gas Act

- First Nations Oil and Gas and Moneys Management Act

- First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act

- Family Homes on Reserves and Matrimonial Interests or Rights Act

- Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act

- Saskatchewan Treaty Land Entitlement Act

- Kanesatake Interim Land Base Governance Act

Influencing legislation:

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act

- Indigenous Languages Act

- First Nations Financial Transparency Act

- Addition of Lands to Reserves and Reserve Creation Act

- First Nations Fiscal Management Act

- First Nations Land Management Act

- Dominion Water Power Act

ISC Portfolio Organizations

Indian Oil and Gas Canada

- Indian Oil and Gas Canada (IOGC) is an organization committed to managing and regulating oil and gas resources on First Nation reserve lands. It is a special operating agency under ISC.

- Indian Oil and Gas Canada Vision: To become a modern regulator of First Nations oil and gas resources.

- Indian Oil and Gas Canada's general responsibilities are to:

- identify and evaluate oil and gas resource potential on Indian reserve lands;

- encourage companies to explore for, drill and produce these resources through leasing activity;

- ensure equitable production, fair prices and proper collection of royalties on behalf of First Nations; and

- secure compliance with and administer the regulatory framework in a fair manner.

ISC Ministerial Advisory Board

National Indigenous Economic Development Board

- The National Indigenous Economic Development Board's (NIEDB) mission is to advise the Minister of Indigenous Services and other federal Ministers on policies, programs, and program coordination as they relate to Indigenous economic development.

- National Indigenous Economic Development Board Vision: A vibrant Indigenous economy, where Indigenous Peoples are economically self-sufficient and have achieved economic parity with Canadian society.

- The Board is comprised of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis business and community leaders from across Canada. It helps governments respond to the unique needs and circumstances of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

Annex A: History of Indigenous Service Delivery

First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

- 1904 – Medical programs and health facilities for Indians were developed in response to smallpox outbreak.

- 1974 – Minister of National Health and Welfare tabled "Policy of the Federal Government Concerning Indian Health Services."

- Mid-1980's – Work was undertaken to transfer the control of health services to First Nations and Inuit communities and organizations through the Strategic Policy, Planning and Analysis Directorate at Health Canada (renamed First Nations and Inuit Health Branch in 2000).

- In response to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the federal government announced Gathering Strength—Canada's Aboriginal Action Plan, which committed to addressing chronic illnesses of Indigenous Peoples, the development of Aboriginal Healing Foundation, and a healing strategy that addresses the legacy of Indian Residential Schools in partnership with the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development.

- Work continues toward the transfer of health services to communities (i.e. British Columbia First Nations Health Authority).

- Efforts remain ongoing to implement orders issued from the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal regarding the implementation of Jordan's Principle.

Schooling and Education

- 1830s – saw the introduction of Indian Residential Schools.

- 1940 – policy of education integration was introduced, enabling Indigenous students to attend provincial school. Issues with this approach included a lack of specialized training to teach Indigenous students and the fact that schools were often located far from students' homes.

- 1972 – the National Indian Brotherhood (later became the Assembly of First Nations) policy on Indian Control of Indian Education was adopted by the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development.

- 1970's – began to address the importance of local community control to improve education, identified the need for more Indigenous teachers and the development of relevant curricula.

- Recent efforts have contributed to federal and provincial legislation that formalizes the local jurisdiction for First Nations communities (i.e. Nisga'a Education Act, Mi'kmaq Education Act).

- Work remains ongoing, in collaboration with Indigenous partners, towards distinctions-based post-secondary education strategies.

Economic Development

- 2000s – saw an increased focus on economic development through legislative approaches to financial management and accountability.

- 2006 – First Nations Fiscal Management Act (FNFMA) was implemented. Includes:

- First Nations Financial Management Board (FNFMB);

- First Nations Tax Commission (FNTC); and,

- First Nations Finance Authority (FNFA).

- 2010 – the Strategic Partnership Initiative was created to provide a coordinated federal response to existing and emerging Indigenous economic development opportunities (e.g., in major projects).

- With the aim of addressing issues of underfunding and onerous reporting requirements for Indigenous communities, Canada entered into the Mi'kmaq-Nova Scotia-Canada Tripartite Forum.

- 2019 – the 10-year grant program was established to advance the New Fiscal Relationship with First Nations.

Community Infrastructure

- Canada provides funding and technical support for community infrastructure. First Nations communities are responsible for the procurement, construction, and operations and maintenance of their community infrastructure.

- Underfunding for community infrastructure on-reserve has resulted in poor living conditions (e.g., overcrowding in homes, mold infestations).

- The Government of Canada has made significant progress in recent years towards improving access to clean drinking water and ending long-term drinking water advisories in First Nations communities. An action plan is in place and initiatives are underway to address all remaining long-term advisories.

- As per the Department of Indigenous Services Act (2019), ISC is working with Indigenous partners on the development, provision, assessment and improvement of infrastructure services, with the ultimate goal, of the transfer of control of infrastructure services to Indigenous organizations.

Child and Family Services

- 1950s – an amendment to the Indian Act allowed governments to provide child welfare services on-reserve which resulted in the Sixties ScoopFootnote 1.

- 2007 – the Enhanced Prevention Focused Approach to Child and Family Services (EPFA) was introduced.

- 2016 – the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ruled funding provided for on-reserve child and family services programming was discriminatory.

- June 2019 – Bill C-92, affirming and recognizing Indigenous Peoples' jurisdiction over child and family services was enshrined into law. The Government of Canada signed a coordination agreement with the Cowessess First Nations in Saskatchewan on July 6, 2021.

- Efforts remain ongoing to work with Indigenous partners to reform the First Nations Child and Family Services (FNCFS) program, which funds prevention and protection services for First Nations children and families living on-reserve.

Governance

- 1980s – Indian Government support programs were created to aid organizations in under taking administrative control over departmental programs. They are now known as the Indigenous Governance and Capacity programs and are currently available for communities.

- New guiding principles, created through the Indigenous Community Development National Strategy (2018), emphasize the need for community governance to: be community-driven, be nation-based, include the recognition of diversity, invest in capacity building, planning and implementation, and be flexible and responsive.

- Governance tools have been developed for communities and institutions to support their process in self-determination.

- ISC is co-developing a policy framework that paves the way for transferring infrastructure service delivery to First Nation partners. The framework encompasses the process and requirements for service transfer to ensure ISC staff and First Nations communities understand the implications of the transfer of control and accountabilities for infrastructure service delivery.

3. Indigenous Services Canada and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada: Division of Responsibilities

Indigenous Services Canada's (ISC) primary responsibilities are the delivery of services and programs to Section 91(24) Indigenous communities, with a particular emphasis on closing the socio-economic gap between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous Peoples and building up the capacity of Indigenous communities so that they have the means and ability to move forward on the path to self-determination.

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada's (CIRNAC) primary responsibilities are to guide and coordinate the whole-of-government relationship with Section 35 rights holders and Indigenous nations; to reach and implement agreements to accelerate self-determination (through self-government and land claim agreements, including reconstituting nations); and to manage northern programing and Arctic Policy.

ISC Responsibilities (lead sector)

- Indigenous Health (First Nations and Inuit Health Branch)

- Housing and Infrastructure (Regional Operations Sector)

- Education (Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector)

- Social Services (Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector)

- Child and Family Services (Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector)

- Indian Status (Regional Operations Sector)

- Governance, Bylaws and First Nations Election Act (Lands and Economic Development Sector)

- Economic Development (Lands and Economic Development Sector)

- Economic Policy

- Aboriginal Entrepreneurship and Business Development

- National Indigenous Economic Development Board

- Matrimonial Real Property

- Lands under the Indian Act (Lands and Economic Development Sector)

- Environmental management (Lands and Economic Development Sector)

- Indian Oil and Gas Canada and First Nations Oil and Gas Management Act (Lands and Economic Development Sector)

- Evaluation (Strategic Policy and Partnerships Sector)

- Emergency Management (Regional Operations Sector)

- Fiscal Arrangements (Strategic Policy and Partnerships Sector)

Shared Internal Service housed in ISC

- Legislative, Parliamentary and Regulatory Affairs (Strategic Policy and Partnerships Sector)

- Communications (Deputy Minister's Office)

- Departmental Library (Chief Financial and Results Delivery Officer Sector)

CIRNAC Responsibilities (lead sector)

Crown-Indigenous Relations

- Permanent Bilateral Mechanisms (Policy and Strategic Direction Sector)

- Inuit and Métis Housing (Policy and Strategic Direction Sector)

- Recognition and Implementation of Rights Framework (Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector)

- Land Claims Negotiations (Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector)

- Modern Treaty and Self-Government negotiations (Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector)

- Specific Claims (Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector)

- Treaty implementation (Implementation Sector)

- Residential Schools Resolution (Resolution and Partnerships Sector)

- First Nations Financial Management Act (Resolution and Partnerships Sector)*

- First Nations Land Management Act (Resolution and Partnerships Sector)*

- Additions to Reserves (Resolution and Partnerships Sector)*

- Audit (Deputy Minister's Office)

* While CIRNAC retains legislative authority/approval over First Nations Land Management Act and Additions to Reserve legislation, operational elements associated with these regimes are be undertaken by ISC (via the regional offices).

Northern Affairs (Northern Affairs Organization)

- Territorial governments

- Devolution

- Arctic and Northern Policy Framework

- Arctic Science

- Nutrition North

- Polar Knowledge Canada

- Contaminated sites

Shared Internal Service housed in CIRNAC

- Human Resources

- Cabinet Affairs (Policy and Strategic Direction)

4. Profiles of Indigenous Services Canada Senior Executives

October 2021

Text alternative for Indigenous Services Canada Senior Executives org chart

- Minister of Indigenous Services

- Deputy Minister: Christiane Fox

- Associate Deputy Minister: Valerie Gideon

- Regional Operations: Senior ADM, Joanne Wilkinson

- Regional Offices South of 60°

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch: Senior ADM, Patrick Boucher

- Regional Operations, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch: ADM, Keith Conn

- Regional Offices First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

- Chief Finances, Results and Delivery Officer: Philippe Thompson

- Child and Family Services Reform: ADM, Catherine Lappe

- Lands and Economic Development: ADM, Kelley Blanchette

- Indian Oil and Gas Canada: Executive Director and CEO, Strater Crowfoot

- Strategic Policy and Partnerships: ADM, Gail Mitchell

- Corporate Secretariat: Corporate Secretary, Kyle McKenzie

- Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships: ADM, David Peckham

- Common services to ISC and CIRNAC

- Human Resources and Workplace Services: Director General, Maryse Lavigne

- Audit and Evaluation: Acting Chief Executive, Stephanie Barozzi

- Communications: Director General, Aruna Sadana

- Legal Services: Senior General Counsel, Marie Bourry

- Regional Operations: Senior ADM, Joanne Wilkinson

Deputy Minister

Name: Christiane Fox

Telephone number: (613) 614-1658

Christiane Fox was appointed to the position of Deputy Minister of Indigenous Services Canada in September 2020. She is also the Deputy Minister Champion of the Federal Youth Network.

Prior to her appointment, Christiane had been the Deputy Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs since November 2019, and the Deputy Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs and Youth from June 2017 to November 2019. She also held several positions at the Privy Council Office, including Assistant Secretary to the Cabinet, Communications and Consultations, Director of Operations, Policy, in the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Relations Secretariat, and Director General of Communications.

Christiane started her career as a Communications Advisor at Industry Canada, now Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, where she worked in Communications, and in Science Policy. She also spent a year with the Competition Policy Review Secretariat, as the Director of Communications and Consultations.

Christiane has a BA in Mass Communications and Psychology from Carleton University, and is a graduate of the University of Ottawa's Masters Certificate Program in Public Administration.

Associate Deputy Minister

Name: Valerie Gideon

Telephone number: (613) 219-4104

In September 2020, Valerie Gideon was appointed Associate Deputy Minister of Indigenous Services Canada.

Prior to her appointment, Valerie held the position of Senior Assistant Deputy Minister for the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) since April 2018, having acted in that position since December 2017. Prior to that role, Valerie was Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations, FNIHB. In 2011–2012, she was Director General, Strategic Policy, Planning and Analysis at FNIHB. From 2007 to 2010, she held the position of Regional Director for First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, Ontario Region, Health Canada. Prior to working at Health Canada, her experience consisted mainly of working in First Nations health advocacy as Senior Director of Health and Social Development at the Assembly of First Nations and Director of the First Nations Centre at the National Aboriginal Health Organization. She was named Chair of the Aboriginal Peoples' Health Research Peer Review Committee of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research in 2004.

Valerie graduated from McGill University (Montreal) in 2000 with a Ph.D. (Dean's List) in Communications (dissertation pertaining to telehealth and citizen empowerment). She previously completed a Masters of Arts in 1996 at McGill. She is a founding member of the Canadian Society of Telehealth and former Board member of the National Capital Region YMCA/YWCA. Valerie is a member of the Mi'kmaq Nation of Gesgapegiag, Quebec, Canada.

Regional Operations

Name: Joanne Wilkinson

Title: Senior Assistant Deputy Minister

Telephone number: (613) 415-5423

Name: Danielle White

Title: Assistant Deputy Minister and Special Advisor

Telephone number: (613) 884-3697

Overview

Regional Operations is responsible for the delivery of national programs and services through seven south of 60° regional offices. Programs include those offered by the Education and Social Development Programs and Partnership Sector as well as the Lands and Economic Development Sector.

Regional Operations is also responsible for managing three national programs, which include Governance Capacity, Community Infrastructure and Emergency Management.

Governance Capacity

Governance Capacity provides funding for band governance and administration: funding to eligible First Nations, Inuit or Innu employers to support pension and benefit plans; core funding to Tribal Councils; and targeted funds to governance capacity development projects. This funding is intended to support Indigenous communities and institutions in the implementation of strong and sustainable governments.

Community Infrastructure

Community Infrastructure works with First Nations governments to support affordable and adequate housing; the provision of clean, safe and reliable drinking water and the effective treatment of wastewater on First Nations lands; the provision of safe schools; and other community infrastructure essential to healthy, safe, and prosperous communities, such as roads and bridges.

Emergency Management

The Emergency Management Assistance Program supports the health and safety of on-reserve First Nations residents as well as their lands and critical infrastructure. This program promotes a four pillar approach to emergency management: mitigation; preparedness; response; and recovery. ISC promotes efficiency by accessing existing resources and services of provinces and territories and emergency management partners to address on-reserve emergencies and reimburses these partners for eligible expenses.

Regional Offices South of 60°

Atlantic Region

Name: Daniel Kumpf

Title: Regional Director General

Telephone number: (902) 397-0207

Alberta Region

Name: Jamie Brown

Title: Regional Director General

Telephone number: (780) 554-4699

British Columbia Region

Name: Allyson Rowe

Title: Regional Director General

Telephone number: (604) 355-3018

Saskatchewan Region

Name: Rob Harvey

Title: Regional Director General

Telephone number: (306) 536-9929

Manitoba Region

Name: Kandice Léonard

Title: Regional Director General

Telephone number: (204) 430-6768

Ontario Region

Name: Anne Scotton

Title: Regional Director General

Telephone number: (613) 794-0014

Quebec Region

Name: Luc Dumont

Title: Regional Director General

Telephone number: (418) 951-7304

Chief Finances, Results And Delivery Officer

Name: Philippe Thompson

Title: Chief Finances, Results and Delivery Officer

Telephone number: (613) 355-0247

Overview

The Chief Finances, Results and Delivery Officer Sector is responsible for providing leadership and ensuring effective management of departmental resources within the legislative mandate. The Sector also provides strategic advice, oversight, and support to the Deputy Minister and the senior executive team to ensure integrity and sound financial controls and management in the planning and operations of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC).

The Sector is responsible for establishing the planning framework for ISC that aligns the mandated outcomes and departmental strategic priorities with resource management via the Departmental Results Framework. The Chief Finances, Results and Delivery Officer leads the reporting to Cabinet and Parliament on outcomes through the Departmental Plan and Departmental Report and the implementation of the Minister's mandate letter commitments.

The Chief Finances, Results and Delivery Officer Sector supports delivery of services through policies, directives and other activities in the areas of financial planning and analysis, accounting and reporting, contracting and procurement, assets and materiel and information management.

The Chief Finances, Results and Delivery Officer is responsible for ISC's Chief Information Officer functions that include information management and technology services, investments structures and controls within ISC, to leverage Information Management and Information Technology reliably, securely, and cost effectively to support effective and efficient business process design and execution.

The Sector is accountable for providing grants and contributions advisory and support services through policies, directives and other activities, including the development of national funding agreements models and guidelines; the establishment of funding agreement service standards; the management of the Grants and Contributions Information Management System; and the national monitoring, compliance and reporting.

In the context of transformation of the Indigenous policy and service space, the Chief Finances, Results and Delivery Officer plays a key role in elaborating and monitoring arrangements, including service level agreements for shared internal services while participating as a service lead in the finance and corporate management space and as a client for those services provided by its sister-department, Crown Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

First Nations And Inuit Health Branch

Name: Patrick Boucher

Title: Senior Assistant Deputy Minister

Telephone number: (613) 946-4884

Overview

Indigenous Services Canada works with First Nations, Inuit, other federal departments and provincial and territorial partners to support healthy First Nation and Inuit individuals, families and communities. Working with partners, the Branch strives to improve health outcomes, provide access to quality health services and support greater control of the health system by First Nations and Inuit.

Subjects

- Coronavirus and Indigenous communities

- Indigenous health care in Canada

- Diseases that may affect First Nations and Inuit communities

- Indigenous mental health and substance use

- Non-Insured Health Benefits for First Nations and Inuit

- Co-developing distinctions-based Indigenous health legislation

- Health care services for First Nations and Inuit

- Family Health

- Environmental issues and Indigenous health

In recent years, First Nations and Inuit health has improved; however, gaps remain in the overall health status of First Nation and Inuit when compared to other Canadians. ISC's FNIHB works with numerous partners to carry out many activities aimed at helping people stay healthy and promoting wellness.

On this shared path to improved health, the Branch funds or delivers:

- Community-based health promotion and disease prevention programs;

- Primary, home and community care services;

- Programs to control communicable diseases and address environmental health issues; and

- Non-insured health benefits to supplement those provided by provinces, territories; and private insurer.

Regional Operations, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

Name: Keith Conn

Title: Assistant Deputy Minister

Telephone number: (613) 204-8698

FNIHB Regional Executives

Atlantic Region

Name: Louis Dumulon

Title: Regional Executive

Telephone number: (613) 946-8104

Quebec Region

Name: Katrina Peddle

Title: Regional Executive

Telephone number: (514) 260-2058

Ontario Region

Name: Garry Best

Title: Regional Executive

Telephone number: (343) 550-6846

Manitoba Region

Name: Pam Smith

Title: Regional Executive

Telephone number: (204) 612-9248

Saskatchewan Region

Name: Jocelyn Andrews

Title: Regional Executive

Telephone number: (306) 203-4580

Alberta Region

Name: Rhonda Laboucan

Title: Regional Executive

Telephone number: (780) 495-6459

Northern Region

Name: Heather MacPhail

Title: A/Regional Executive

Telephone number: (613) 301-5984

Child and Family Services Reform

Name: Catherine Lappe

Title: Assistant Deputy Minister

Telephone number: (604) 340-7703

Overview

In March 2018, ISC created the Child and Family Services Reform Sector in order to address the over-representation of Indigenous children and youth in care in Canada. The Sector is guided by the government's commitment to six points of action following a two-day Emergency Meeting on Indigenous Child and Family Services held in

January 2018 with Indigenous partners, provincial and territorial representatives, youth, experts and advocates:

- continuing to fully implement the orders from the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, and reform First Nations child and family services program to make it truly child-centered and community-directed;

- working with partners to shift the focus of programming to culturally appropriate prevention, early intervention, and family reunification;

- supporting communities to exercise jurisdiction and working with partners to implement child and family services legislation;

- accelerating the work at tripartite and technical tables that are in place across the country to support reform;

- supporting Inuit and Métis Nation leadership in their work to advance meaningful, culturally appropriate reform of child and family services; and

- developing a data and reporting strategy with provinces, territories and Indigenous partners.

The Child and Family Services Reform Sector ensures the full implementation of the orders by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal related to child and family services, and works with partners on implementing the co-developed An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, which came into force on January 1, 2020.

Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships

Name: David Peckham

Title: Assistant Deputy Minister

Telephone number: (613) 894-4239

Overview

The Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector is responsible for social and education programs.

The Sector works to strengthen both policy and program management functions, including program compliance and national consistency, and to monitor program performance and effectiveness for two of ISC's largest program areas: Education and Social Development.

The Sector's mandate is twofold:

- to provide First Nation men, women, children and families with the supports necessary to help them achieve education outcomes comparable to those of other Canadians; and

- to assist eligible on-reserve residents to foster greater self-reliance, improve quality of life, reduce or eliminate family violence, and participate more fully in Canada's economic opportunities.

The Sector is closely linked with eight regional offices (seven South of 60° and one in the Yukon) and the Regional Operations Sector.

Education related programs and services are delivered in collaboration with partners including First Nations regional education organizations and provinces. Other federal departments, particularly Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, are also partners in funding and delivering education-related programs and services.

Social programs and services are delivered in collaboration with First Nation organizations, provinces, territories and other federal departments. These partners includes: Health Canada, Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, the Public Health Agency of Canada, provincial and territorial governments, the Assembly of First Nations, and others.

Strategic Policy and Partnership

Name: Gail Mitchell

Title: Assistant Deputy Minister

Telephone number: (613) 608-5029

Overview

The Strategic Policy and Partnerships Sector of ISC was established to support ISC sectors in the improvement and transfer of Indigenous services to Indigenous Peoples, for Indigenous Peoples, by Indigenous Peoples. The Strategic Policy and Partnerships Sector serves as an internal driver of change by supporting ISC sectors in improving services and enabling Indigenous control.

The Sector includes the following branches:

Strategic Policy

- Provides strategic policy analysis and advice in fulfillment of the Minister's mandate, ISC's transformation agenda, and federal policy direction.

Evaluation and Policy Re-Design

- Identifies innovative policy interventions and partnerships to improve and transfer services, and evaluate the success of transferred services through an Indigenous lens.

Strategic Research and Data Innovation

- Provides a robust and innovative evidence base for decision making to ensure that new and redesigned policy initiatives reflect Indigenous ways of knowing and doing. Examines long-term trends and undertake forecasting to keep ahead of emerging issues and identify challenges and opportunities.

Fiscal Arrangements

- Works to address longstanding challenges in how Indigenous services are funded and how funding relationships are managed with a long-term agenda.

Lands and Economic Development

Name: Dr. Kelley Blanchette

Title: Assistant Deputy Minister

Telephone number: (613) 447-2462

Overview

The Lands and Economic Development Sector manages a suite of programs, legislation and relationships with Indigenous organizations that together promote entrepreneurship, build economic development capacity and foster the creation of wealth. Lands and Economic Development also leads the administration of reserve land and supports environmental protection on reserve, both critical elements related to stimulating economic development.

Lands and Economic Development consists of three branches: Economic Policy Development Branch, which provides policy options/direction and coordination for the sector; Economic Business Opportunities, which administers proposal-driven programs for economic development projects; and Lands and Environmental Management, which works with First Nations and First Nation organizations on the administration of lands, the expansion of reserve lands through additions to reserve, the remediation of contaminated sites and the management of waste sites on-reserve. Lands and Economic Development also oversees a special operating agency (Indian Oil and Gas Canada), responsible for the management and regulation of oil and gas development of reserve lands.

The Sector also works with institutions, such as the Lands Advisory Board and the First Nations Land Management Resource Centre to improve First Nations lands and environmental governance, and leads lands modernization initiatives to improve existing legislation and regulations. Additionally, the Sector undertakes research and analysis to support policy development, fosters partnerships with stakeholders and coordinates a whole-of-government approach on Indigenous economic development. All sector efforts contribute to the ultimate goal of increasing the participation of Indigenous Peoples in the economy.

Regional offices across Canada implement Lands and Economic Development's programming and services and carry out the administration of the Crown's statutory and fiduciary obligations under the Indian Act. While the regions get their direction from Lands and Economic Development in terms of the activities that they perform to promote lands and economic development, they formally report to the Regional Operations Sector.

Corporate Secretariat

Name: Lana Thomas

Title: A/Corporate Secretary

Telephone number: (613) 799-1476

Overview

The Corporate Secretariat provides executive services to the Minister's Office, the Deputy Ministers' Offices, the Associate Deputy Ministers' Offices, as well as delivering key corporate functions across ISC. The Secretariat supports ISC on four key areas::

Executive Services Operations: comprised of three divisions responsible for coordinating and reviewing correspondence and briefing materials for the Deputy Ministers and the Minister:

- Officials Trips Directorate (MinTrips): works with the Minister's Offices, sectors, regions and Communications to ensure horizontal coordination of Ministerial trip planning. Ensures a strategic, coherent, and consistent approach in the development of material for, and in follow up to trips;

- Ministerial Correspondence Directorate: reviews and provides final quality control for briefing notes and correspondence to the Minister and Deputy Ministers, as well as oversight for departmental processes and practices associated with correspondence; and

- Governance and Planning Coordination: responsible for the coordination of material for ministerial briefings, invitations, transition, portfolio coordination, and final documentation preparation for additions to reserve.

Planning and Resource Management Directorate: responsible for providing administrative support services for the Minister's Office, Deputy Ministers' Offices, and the Corporate Secretariat, including business planning, finance, human resources, and contracting services.

Indigenous Employee Secretariat

Supports the work done by Indigenous Advisory Circles and Indigenous employee networks and serves as an information centre through which Indigenous and non-Indigenous employees can enquire about various Indigenous related programs, initiatives and events.

Access to Information and Privacy Directorate (shared service with Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada): receives all access to information and privacy requests and, working with sectors and regions, compiles the appropriate responses in accordance with the requirements of the Access to Information Act and Privacy Act.

5. Profiles of Shared Services Senior Executives

Legal Services Unit

Name: Marie Bourry

Title: Senior General Counsel

Telephone Number: (819) 953-0170

Overview

The Legal Services Unit provides a complete range of specialized legal advice and support to both Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) in relation to all their business lines. This includes legislative initiatives, litigation, policies and programs.

The Legal Services Unit is located at Headquarters in Gatineau, while its Treaties and Aboriginal Government-Negotiations West Section is located in Vancouver. The Legal Services Unit is part of the Aboriginal Affairs Portfolio of the Department of Justice Canada.

The Senior General Counsel is a full member of the ISC's Executive Committee and various management committees and, as such, provides legal advice as well as legal policy and strategic policy advice. As the Head of the Legal Services Unit, the Senior General Counsel brings forward legal concerns and advice around risk management relating to matters within ISC and CIRNAC's purview. The Senior General Counsel is the primary interface between ISC and CIRNAC and the Department of Justice Canada.

Counsel in the Legal Services Unit assess the legal risk of specific initiatives within the broader policy context, identify solutions to legal issues and work with departmental officers to develop strategies to address real or potential legal issues.

Human Resources and Workplace Services Branch

Name: Maryse Lavigne

Title: Director General

Telephone Number: (819) 994-7398

Overview

The Human Resources and Workplace Services Branch provides services, advice and support to both ISC and CIRNAC in the areas of Human Resources Management; Security and Accommodations; Occupational Health and Safety; and Integrity, Values and Ethics and Conflict Resolution.

Good people management is the cornerstone to delivering the ISC and CIRNAC mandates. While Deputy Ministers have the primary responsibility for ensuring good people management, the accountability is sub-delegated to managers across their organizations.

Key people management priorities include:

- continuing work on blueprint 2020 and the renewal of the Public Services;

- providing healthy workplaces conducive to employee engagement and excellence;

- addressing mental health stigma; and

- responding to Public Service Employee Surveys.

The workforce issues and opportunities at ISC and CIRNAC resemble those of other large departments. For instance, issues facing some employees with respect to the implementation of the Phoenix system across the Public Service remain a key challenge. The Branch is keeping track of the unresolved cases and has put a team to follow up with Public Service and Procurement Canada officials to address them.

What is unique to ISC and CIRNAC is the need to recruit and retain Indigenous employees and those in the North. Employee engagement is important across all occupations categories, across all regions, and has an effect on achieving departmental objectives. Addressing workplace issues and opportunities will ensure that we have the right working conditions for employees in a high performing organization and generate high employee engagement and productivity.

Communications

Name: Aruna Sadana

Title: Director General

Telephone Number: (613) 297-3311

Overview

Public perception of the government's handling of Indigenous issues is shaped by Canada's long, complicated and sometimes difficult relationship with Indigenous Peoples.

The Communications Branch acts as an advisor to colleague departments' Communications branches on Indigenous topics and convened an interdepartmental working group on reconciliation in order to coordinate messages across departments for a whole of government perspective. The Branch also supports the Prime Minister's Office and the Privy Council Office on Indigenous files.

The Communications Branch operates as an integrated corporate function. There is constant and close collaboration with the Minister's Office and the Office of the Deputy Minister to ensure that the Minister's and ISC's objectives, programs, services, and policies are communicated in a coherent way.

The Communications Branch reports directly to the Deputy Minister and is headed by a Director General with the support of a Senior Director and two Directors. While the Communications Branch continues to transform into two distinct Communication branches (one for ISC and one for CIRNAC), many Communications functions remain joint between both ISC and CIRNAC.

Audit

Name: Stephanie Barozzi

Title: Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive

Telephone Number: (613) 218-9112

Overview

Stephanie Barozzi is the Chief Audit Executive (CAE) for ISC and the Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive for CIRNAC. In this role, she has the responsibility for internal audit for both departments, while Gail Mitchell, Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic Policy and Partnerships Sector, has the responsibility for evaluation within ISC.