Former Indian Residential Schools - Environmental Scan: Status of Sites and Buildings

February 2024

Disclaimer

This Environmental Scan on the status of former Indian residential schools and its companion data set is based on publicly accessible sources. It is provided for context and discussion purposes only. For the most current and accurate information, research should be independently conducted on the status of former sites and buildings.

Questions, comments, suggestions - contact: Indigenous Services Canada's Residential Schools Legacy Secretariat, IRS-ISC.PI-SAC@sac-isc.gc.ca

Table of contents

Trigger warning

This report discusses topics that may be distressing and awaken memories of past traumatic experiences and abuse.

The National Indian Residential School Crisis Line provides 24-hour crisis support to former Indian Residential School students and their families toll-free at 1-866-925-4419.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis seeking immediate emotional support can contact the Hope for Wellness Help Line toll-free at 1-855-242-3310, or by online chat at hopeforwellness.ca.

Executive summary

The Indian Residential Schools (IRS) Environmental Scan summarizes the status, jurisdictional ownership and condition of sites and buildings associated with the 140 former residential schools recognized in the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

Through limited engagement and available public information sources, the IRS Environmental Scan presents the status of residential school buildings and sites including the applicable jurisdictions (e.g. provincial, territorial, municipal, self-governing, modern treaties), type of ownership (e.g. public, private entities), and how remaining buildings are being used. The IRS Environmental Scan also identifies areas of future research including identification of specific land title holders, potential public and private third-party interests, and possible overlapping interests.

Complementary to the IRS Environmental Scan, ISC developed an interactive mapping tool and funded a report written by the National Center for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) on engagement considerations for future decisions about former residential school sites and buildings.

The NCTR shared in their report a number of considerations, approaches, and principles that should be taken in account for any local or national engagement concerning future use or protection of former Indian residential school sites and buildings.

Many communities, Survivors and researchers have been seeking information on the status of former residential school lands. The Independent Special Interlocutor on Unmarked Burials and Missing Children has noted the need to document current ownership of former residential school sites in order to be able to protect sites and access to the grounds that are privately held.

Building on publicly accessible research and data sets (i.e., Rosa Orlandini 2018), the IRS Environmental Scan adopted an open-source approach to ensure partners and communities will have access to the data compiled. This is in keeping with Indigenous Services Canada's commitment to Indigenous Data Sovereignty, as mentioned in the 2023-2026 Data Strategy for the Federal Public Service and as guided by the First Nations Information Governance Centres principles of Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP).

Results of this project will enable a shared understanding of the complexities, ownership, and status of former residential school buildings and sites. The data is subject to regular updates and will be updated as site circumstances change and new information is available.

Introduction

Purpose

The purpose of the report is to provide an overview on the findings of an IRS Environmental Scan conducted in 2022-2023 of the current condition, jurisdictional ownership, and complexities related to residential school buildings and sites.

Context

The Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement was the result of a national class action litigation on behalf of former students of the Indian Residential Schools system. Implementation of the Settlement Agreement began on September 19, 2007 and addresses the legacy of the Indian Residential Schools. The list of 140 recognized Indian residential schools (often called federal hostels in northern Canada) by province and territory can be found on the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement website. Information about other institutions requested to be added to the Settlement Agreement through Article 12 is also available.

On May 27, 2021, Tk'emlúps te Secwe̓pemc First Nation in British Columbia announced that a search by ground penetrating radar located unmarked burials of children at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. This was a confirmation of known stories for Indigenous peoples, and a tragic reminder of the history and legacy of residential schools.

Following this confirmation, federal departments deployed efforts to support communities, Survivors and families. On August 10, 2021, Canada announced $321 million to enable Indigenous-led, Survivor-centric and culturally informed initiatives and investments to help Indigenous communities respond to and heal from the ongoing impacts of residential schools and in direct response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's (TRC's) Calls to Action 72-76:

- $83 million added to CIRNAC's Residential School Community Support fund for searches of burial sites and commemorate the children who died at residential schools (an additional $122 million over 3 years was announced in Budget 2022).

- Creation of a National Advisory Committee, to advise Indigenous communities and the government about work to find and identify the children.

- $9.6 million to support initiatives that commemorate the history and ongoing legacy of residential schools including activities marking the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

- $20 million for a national monument in Ottawa to honour Survivors and children taken from their families and communities.

- Appointment of a Special Interlocutor to make recommendations related to federal laws, regulations, policies and practices surrounding unmarked and undocumented graves and burial sites at residential schools.

- $107.3 million in 2021-22 to increase access to trauma informed health and cultural support services and expand access to ensure all First Nations and Inuit are eligible for these supports in 2021-22 (renewed in Budget 2022 for an additional two years).

- $100.1 million over 2 years starting in 2021-22 to help communities begin to address on-reserve school buildings and associated sites that were once used for residential schools. This includes community engagement activities, site clean-up and remediation, building demolition, renovations to existing buildings and the construction of new facilities to accommodate services currently being held in these buildings on reserve.

To further support Survivors and communities in addressing the legacy of residential schools, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) undertook the IRS Environmental Scan in 2022-2023. The IRS Environmental Scan includes contemporary information on location, ownership, and condition of residential school buildings and sites building on publicly available data sets (Orlandini, 2018) and publicly available information.

Limited engagement was conducted with key partners such as the NCTR, provinces and territories, other federal departments, academic and Indigenous technical experts and researchers, and some partnership tables. The NCTR also provided Survivor-first considerations to support co-development of any local or national engagement concerning future use or protection of former Indian residential school sites and buildings.

Through its regional offices, ISC reached out in 2022 to all 52 First Nations who had residential schools on their reserves. This engagement provided the department with a contemporary understanding of First Nation use of existing former residential school buildings that many First Nations inherited from the federal government when the residential schools ceased to operate.

Unlike the on reserve sites, less is known about the status of residential school sites located off-reserve and in the North. Many sites are now owned by various federal, provincial, territorial, municipal or Indigenous governments, churches, or private entities. Most former residential school buildings still in use are leased for a variety of public and private purposes.

It is acknowledged that some of the 140 residential schools had more than one location during their operation resulting in approximately 174 unique site locations. The focus of the IRS Environmental Scan was on the last site of each residential school. Available previous site locations information was also collected. Some residential schools operated for short periods; others closed in the early 1900s.

This report is part of a broader strategy to improve accessibility to information relevant to former residential schools. For example, ISC's IRS Mapping Application uses site location data provided by the NCTR (Orlandini, 2018) and layers it with Government of Canada Open Data (First Nation and Inuit Communities, reserve boundaries, and historical aerial photography provided by Natural Resources Canada). In addition to the collection of geospatial data to situate and provide historical context to the residential school sites, the application has search, filtering, measurement, and print tools to assist users with analysis or the creation of their own maps.

Methodology

Data considerations

- The term 'residential school site' refers to the property that the main Indian residential school or federal hostel buildings were located on. Following the same methodology as Rosa Orlandini (2018), a residential school was considered to have a separate site if it expanded or moved to a location/property more than five kilometers away.

- Sites were considered to be on reserve if the point of the main school building was within the boundaries of a reserve.

- The IRS Environmental Scan takes an open data approach to the collection of information, and as such is disclosed without any terms or conditions governing their use.

- The information compiled for the IRS Environmental Scan is gathered from publicly available sources. This includes newspaper articles, public archives, community/survivor organization websites, public mapping tools (e.g. Aboriginal Treaty Right Information System (ATRIS), land title mapping, community development maps, Google Map overlays), and research reports (e.g., NCTR narratives on each residential school). See Annex B for links to these sources.

- The dataset on which the IRS Environmental Scan is based with more detailed information may be requested by contacting IRS-ISC.PI-SAC@sac-isc.gc.ca.

Scope and research caveats

- Institutions: The project gathered information on the 140 institutions recognized in the IRSSA to better understand the current status of former Indian residential schools and federal hostels. Non-IRSSA schools, federal day schools, institutions in the Newfoundland and Labrador Anderson Settlement Agreement, federal hospitals and sanatoriums were out of scope.

- Land status changes during operating dates: The IRS Environmental Scan on the 140 IRSSA institutions focuses on what is known about each site when it closed as an Indian residential school. The geographic size of the grounds of many residential schools shifted over time especially those that operated over several decades or longer. Some were initially centred around a church, then may have expanded as more buildings were constructed and lands added for agricultural purposes, with the footprint of many residential schools becoming smaller in 1960s and onwards when most became student residences. Details about the evolution of each site and associated buildings during their dates of operation as a federal Indian residential school are found in the historical narratives available via the NCTR's archival portal which include digital copies of available maps, surveys and plans.

- Land ownership status: Information on the current status of land ownership refers to the present-day status and type of ownership in 2022-2023, and not the ownership or condition of any buildings when the residential school closed. The Canadian common law/civil law concept of Property Law is used to conceptualize land and presumes who "owns" the land. It is acknowledged that land ownership within the IRS Environmental Scan may be considered to be a colonial construct.

- Land ownership and land titles:The information in the IRS Environmental Scan is based on GPS information to determine the type of ownership currently involved at each former residential school site (e.g. on reserve, private, public, mixed ownership). Identification of specific ownership of each former residential school location, e.g. the name of the owners for privately owned sites, was not undertaken. Many residential school properties off-reserve were subdivided after the operation of the residential schools ended, and sites may have a number of ownership types as well as multiple private owners. Land title searches would be needed for more specific ownership information, and the current GPS information would have to be converted to plan and lot numbers.

- Location precision: The location of former residential school buildings and whether they are on or off-reserve are based on the GPS data points of the main residential school buildings, as gathered by NCTR via Google Earth satellite imagery in 2015. The exact locations of the secondary school buildings (e.g. barns, out buildings, staff houses) have not been verified.

- Third party interests: Third party interests in former residential school sites have not been identified, such as right of ways or easements for utility or transportation corridors through the properties, lease-holds, liens or other encumbrances from third parties.

- Provincial/territorial jurisdiction: The precise jurisdictional role for provincial and territorial governments with respect to former residential school sites located off-reserve requires further research in some cases. Even where sites have no provincial ownership, there may still be a provincial role. For example, provincial roadway repair may be needed for roads that cross former residential school sites.

- Modern treaties: The dynamic of land ownership and land management of particular former residential school sites within modern treaty areas is unique to each agreement. In some cases, ownership of buildings lies with a Hamlet or municipality, but the management of the land is through a land corporation. Every agreement manages their land differently.

- Buildings: On some sites with no remaining former residential school buildings, new buildings or structures may have built on the former school grounds. Specifics on usage of non-residential school buildings built on former residential school sites are out of scope for the current project. Data is also limited on locations of foundations or other underground infrastructure (e.g. utility pipes, fuel tanks) when buildings were covered over when they were demolished. Historical details about buildings are available through the research narratives for each residential school accessible through the NCTR's archival portal.

- Law: The IRS Environmental Scan does not include information on how Western laws apply to former residential school sites (i.e., federal, provincial/territorial and municipal) or how sites relate to Indian Act band council resolutions, UNDRIP Free Prior and Informed Consent, Constitution Act Section 35 and the Duty to Consult. In addition, the IRS Environmental Scan does not contain information on Indigenous laws, including ceremonies and protocols, that would apply to former residential school buildings and sites.

- Community/cultural connections: The scan does not include information related to the communities impacted by residential schools and their cultural connections to these buildings and sites. It does not include information on commemoration of these sites, or survivor organizations.

- Publicly accessible data and community privacy: The information collected in the IRS Environmental Scan is from publicly available sources, and care has been taken to only use reliable and credible sources of information. The goal is to offer access to common public data and information, understanding that researchers, including communities and survivors, are seeking information related to former residential school sites and buildings.

- Updates: Site and building information is continually evolving, especially from community engagement. The IRS Environmental Scan database will be updated as new information is received.

Definitions

Land tenure (ownership)

- Federal Land Tenure: This refers to sites on federal Crown land and considered part of the federal real property inventory. For example, the former Churchill residential school site is now part of the Transport Canada owned airport.

- Provincial Land Tenure: This refers to land owned and controlled by a province, for example, Guy Hill residential school (2nd location) is within Clearwater Lake Provincial Park, Manitoba.

- Municipal Land Tenure: This refers to land owned by a municipality. For example, most hamlets in the North West Territories are considered as officially designated municipalities.

- Private Land Tenure: This refers to land owned privately (e.g. freehold, fee simple), and leaseholds, pending ownership confirmation.

- Indigenous Owned Land Tenure: This refers to lands owned privately by an Indigenous government, organization or company. For example, Sioux Valley Dakota Nation purchased the part of the former Brandon residential school site in Manitoba.

- Mixed Land Tenure: There are former residential school properties that were subdivided and now consist of different jurisdictions and ownership type. For example, part of Fort Vermilion (St. Henri) is owned by the Catholic diocese, part is administered by the Province of Alberta. As another example, the site of the Federal Hostel at Arviat now has a church and a health center.

Building status

Buildings are divided into two types:

- Main School Building: These refer to the main residential school building typically where students resided and ate, and often had classrooms and the principal's office.

- Out Buildings: This refers to land owned and controlled by a province, for example, Guy Hill residential school (2nd location) is within Clearwater Lake Provincial Park, Manitoba.

Building status is divided into five categories:

- Present - in use: Building(s) associated with the former residential school are standing on the site and are currently being used.

- Present - not used: Building(s) associated with the former residential school are still standing on the site but are not currently being used.

- Remnants remain: Remnants associated with the residential school are present (e.g. foundation, driveway).

- No IRS buildings: Buildings associated with the residential school are no longer standing on the site. This is sometimes referred to as "no buildings." Site may have buildings constructed after the residential school closed.

- Undetermined: Status of buildings associated with a former residential school not known.

Findings

Overview

The findings are based on the data available as of December 2023; findings may change as more information becomes available. The 140 former residential schools recognized in the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement occupied a total of 174 sites, with 76 located on reserve and 98 off-reserve. Of the 140 residential schools, 34 were located North of 60, and 106 were South of 60. A summary of the IRS Environmental Scan findings is provided below.

IRS Environmental Scan: summary of findings

140 residential schools in the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement occupied 174 sites

On Reserve (76 Sites)

- 31 buildings in use on 17 sites.

- 2 former schools designated national historic sites.

- ISC engaged 52 First Nations who had residential schools: communities at different stages of readiness for addressing sites and buildings, with many prioritizing site investigations.

- First Nations inherited former buildings from Canada. Some have been demolished, some continue to be used by communities. Others have been repurposed as post-secondary institutions.

Off-reserve and North (98 Sites)

- 23 buildings in use on 17 sites

- 2 former schools designated as national historic sites

- 2 included in other national historic sites

- 25 wholly privately owned

- 7 fully or partially on federal Crown land

- 5 fully or partially owned by Indigenous entities

- 17 on provincial or territorial Crown land

- 7 on municipal land

- 40 have mixed types of ownership/multiple jurisdictions, (e.g. Indigenous, private, federal, provincial/territorial, church, modern treaties); many sites owned by multiple private owners

- 10 partially or fully church owned

On reserve

- On reserve, there are 31 buildings on 17 sites still in use by First Nations. Some communities are using a number of buildings; for example, there are four former Kamloops Residential School buildings in use by the Tk'emlúps te Secwe̓pemc First Nation. There are about 37 sites on reserve elsewhere that have no former residential school buildings remaining.

- Some reserve boundaries have changed over time, complicating confirmation of some locations of former residential school sites on reserve. Some residential school sites on reserve land were surrendered by Indian Affairs to churches. While most of these lands eventually reverted to reserve land status, a small number of these sites remain as "donut hole" land parcels not yet converted to reserve land, and may be part of Additions to Reserve requests. For example, former residential school sites at Lytton, British Columbia or Pine Creek, Manitoba.

- Administrative responsibility for on reserve sites and buildings is typically with the local First Nation via the Indian Act or the Framework Agreement on First Nations Land Management. Some First Nations may have allocated parcels of reserve land to individual band members (i.e. Certificate of Possession holders) or designated lands for specific purposes. Further research is needed to confirm whether former residential school sites may be implicated in these designations.

- In several situations, former residential school buildings on reserve are not administered by a First Nation government but by affiliated entities such as an independent board (e.g. University Blue Quills), an economic development corporation (e.g. Portage la Prairie Indigenous Residential School Museum), or an Indigenous company (e.g. St. Eugene's Resort ownership consists of four Ktunaxa communities of ʔAkisq̓nuk, ʔAq̓am, ʔAkink̓umǂasnuqǂiʔit, Yaqan nukiy and the Shuswap Indian Band as St. Eugene Mission Holdings Limited).

Off-reserve and in the North

- Off-reserve, there are 17 sites that have former residential school buildings present and in use. In some cases, there are multiple buildings or remnants remaining on the site. Several sites have buildings that have been constructed on top of the site where the former residential school buildings were located.

- In the North, 34 former residential schools were located in the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut. South of 60, Ontario has the most off-reserve sites at 16 out of 24 (67% of sites).

- The ownership of off-reserve sites is in some cases complicated to determine. The following is the jurisdictional breakdown of the 98 sites off-reserve and in the North:

- 25 privately owned

- 7 fully or partially on federal Crown land

- 5 fully or partially owned by Indigenous entities

- 17 on provincial or territorial Crown land

- 7 on municipal land

- 40 have mixed types of ownership/multiple jurisdictions, including modern treaties

- 10 partially or fully church owned

- The numbers do not add up to 98 as sites may fall under more than one category. Those indicated as being partially owned are also included under mixed ownership, and church owned properties are also counted as privately owned or mixed.

- Many Indian residential school properties were subdivided into multiple lots after closing as a residential school, leading to in some cases several jurisdictions for one site. For example, one corner of the former building may be on a lot that is municipal but a large portion of the former grounds may be owned by a private owner.

- Residential school buildings and sites intersect with broader land considerations that vary across the country (e.g., settlement lands, historic and modern treaties).

- There are at least 25 former sites on private properties, sometimes with several different private owners for the same site, presenting potential access challenges. Access to private property is dependent on the individual owner(s).

- Information on former residential school sites in the territories is often limited, given the remoteness of some of the schools and relatively short duration of operation. For example, Belcher Islands maps are not accessible even with the use of Google satellite imagery.

- Off-reserve former sites range from being on from settlement lands to urban municipal areas.

Self-Government and modern treaty

- As of December 2023, there are about 38 former residential school sites located on lands of 15 self-government and modern treaty agreements.

- Most sites within a modern treaty (e.g. Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement) and/or self-government agreement are included in the "mixed" category as there are multiple jurisdictions involved in the management of these lands. Examples include sites within Hamlets under the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement and managed by a land corporation (Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.), and Modern Treaty sites having joint land management protocols.

- There are numerous forms of co-management of land, water and other resources in these sites, including shared jurisdictional authority between Indigenous peoples and territorial, provincial and federal governments. There can be many organizations and communities involved in land management, and more research is needed to understand how land tenure and land management work together.

- Given ongoing modern treaty negotiations, land tenure of some sites could change over time.

Land tenure

- Off-reserve sites, there are 25 wholly privately owned, 7 fully or partially on federal Crown land, 5 fully or partially owned by Indigenous entities, 17 on provincial or territorial land, 7 on municipal land, 40 where there is mixed ownership (by multiple jurisdictions), and 10 partially or fully church owned.

- The privately owned sites may contain instances where a First Nation has purchased land in anticipation of adding it to reserve land or for economic development purposes. These details will require title searches to determine specific ownership of the sites. As well, the private land category may have multiple private landowners for one site.

- There are currently 7 sites that are associated with federal Crown lands. The residential schools (and their alternative names) and the custodial departments are:

- Coqualeetza (Chilliwack), B.C. (CIRNAC)

- St. George's (Lytton), B.C. (CIRNAC)

- Brandon, MB, (site partially owned by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada)

- Churchill Vocational Centre, MB (Transport Canada)

- Cecilia Jeffrey (Kenora), ON (ISC)

- McIntosh (Kenora), ON (ISC)

- Pelican Lake (Pelican Falls), ON (ISC)

- Some of these Crown owned sites may eventually transition to reserve land (subject to an approved request via the Addition of Lands to Reserve and Reserve Creation Act).

- There are sites that are not entirely owned by the federal government but there may be a designation on or near the site (i.e. waterways, roadways and utilities), or there may have been a railway that crossed near the school. These specifics are not currently captured in the IRS Environmental Scan.

- There are ten sites that are owned or partially owned by a church entity. They are:

- Fort Vermilion (St. Henri), AB - Roman Catholic

- Grouard (St.Bernard's), AB - Roman Catholic

- Lac La Biche (Notre Dames des Victoires), AB - Roman Catholic

- Lesser Slave Lake (St.Peter's), AB - Anglican

- Sacred Heart (Peigan), AB - Hutterite (not church denomination who operated the residential school)

- St. Paul's (Squamish), BC - Roman Catholic

- Hay River (All Saints, St. Peter's), NWT - Anglican

- McKay (Dauphin), MB - Church of Christ (not church denomination who operated the residential school)

- Shingwauk (Wawanosh), ON - Anglican

- Thunderchild (St. Henri), SK - Roman Catholic

- There are four sites that have mixed ownership, that is, are not fully church owned. One of these is Fort Vermilion (St. Henri) - where the Roman Catholic Church owns a church parcel, while the courthouse is on lands administered by the Province of Alberta. The other three sites are: Grouard (St.Bernard's) - Roman Catholic, Hay River (All Saints, St.Peter's) - Anglican, and Shingwauk (Wawanosh) - Anglican.

- Two sites (McKay and Sacred Heart) are owned in full or in part by a denomination that did not operate the residential school but were purchased later by church groups not affiliated with the original residential schools. Only seven of the 140 Indian residential schools are partially owned by the church that ran the residential school.

Building status

- Based on information available in 2023, 54 former residential school buildings at 34 sites are still in use. See Annex A, Table 2 for full list.

- Residential schools often had a number of buildings on the grounds. Many had a prominent 2-3 storey main building that usually held administration, classroom and dormitory space with several outbuildings including staff residences, garages, barns, sheds, recreation spaces (e.g. outdoor rinks, pools) and other utility buildings. Some of the schools may have been demolished or burned down (fires destroyed many buildings while residential schools were operating) and rebuilt at different locations at the site.

- Buildings 'present and in use' off-reserve are sometimes used to provide programming that support Indigenous peoples or may otherwise be used by Indigenous peoples, but are not necessarily specifically for Indigenous community use. For example, Community Services offered at the former McKay school are for the people of Dauphin, Manitoba and are not culturally-based community services.

- On some sites with no remaining former residential school buildings, there may be building(s) built over top of the former school grounds after residential school buildings were demolished, or foundations may have been otherwise covered over.

- There may be buildings built on the site after residential school buildings were demolished. For example, the airport in Churchill Manitoba is built on the former site of the Churchill Residential School.

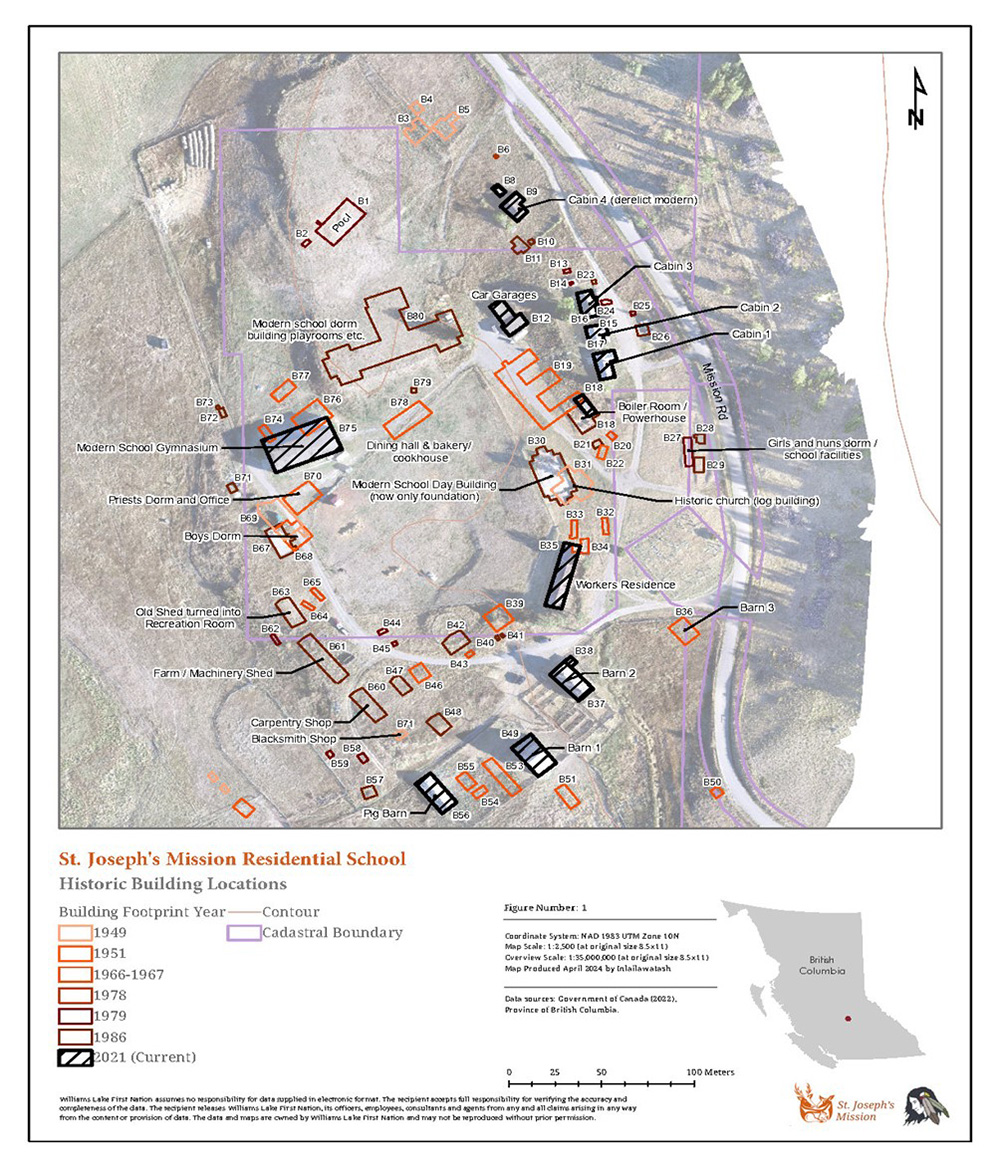

Text alternative for Illustration 1: Building map of the St. Joseph's Mission, courtesy of Williams Lake First Nation

The image shows the footprints of the various buildings that existed at different points of time, from 1949 to 2021, on the grounds of the former St. Joseph's Mission Residential School. The buildings are colour coded to represent what year they were constructed. Some of buildings that still exist as of 2021 include the modern school gymnasium, workers residence, cabins, and barns. The modern school day building, the modern school dorm and playrooms, girls and nuns dorms, sheds, carpentry and blacksmith shops still existed in the 1970s and some into the 1980s.

This map is an example of the multitude of buildings that were commonly associated with an Indian residential school. St. Joseph's Mission (also known as Cariboo Industrial School) operated from 1891 to 1981, about 10 kilometres south of Williams Lake First Nation's main residential reserve community. Typical of a large residential school in Western Canada, its grounds included 20-30 buildings constructed at different times including outdoor swimming pool and arena. More info can be found at: Williams Lake First Nation (wlfn.ca)

Historical designation

- Through the National Program of Historical Commemoration, Parks Canada and the Historic Sites and Monuments Board considers nominations for national historic designations. In 2020, the Residential Schools System was declared as a National Historic Event.

- To date, four former residential school sites that have been designated as national historic sites: The former Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School (Manitoba) and the former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School (Nova Scotia) were designated as national historic sites in September 2020. In July 2021, the former Shingwauk Indian Residential School (Ontario) and the former Muskowekwan Indian Residential School (Saskatchewan) were also designated as national historic sites.

- The former mission at Lac La Biche (Notre Dames des Victoires), Alberta, and the Hay River Mission Sites are also part of other national historic sites but not as former residential schools.

- Several former residential school sites have provincial or territorial historic designations, including:

- Holy Angels (Fort Chipewyan), Alberta

- Lac la Biche (Notre Dame des Victoires), Alberta

- St. Augustine (Smokey River), Albert (Provincial Historic Resource)

- St. Joseph's (High River, Dunbow), Alberta (Provincial Historic Resource)

- Kamloops (St. Louis), British Columbia

- Battleford, Saskatchewan

Engagements

Indigenous Services Canada

Since March 2022, ISC has undertaken limited engagement in support of the work of the IRS environmental scan, including:

- Engagement with 52 First Nations who had residential schools on their reserves.

- Limited engagement with provincial/territorial governments, academic and Indigenous technical experts and researchers, existing partnership tables, and through attendance at national and regional residential school gatherings.

- Commissioned the NCTR to prepare a report on engagement considerations and principles.

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

The NCTR produced a report in 2023 for ISC called Creating an Engagement Plan with Indigenous Communities. The report includes a high-level discussion on the considerations and approaches when developing engagement plans with Indigenous peoples, communities, and Nations about the future use or protection of former residential school sites and buildings.

The report outlines the following principles for creating meaningful and relevant engagement planning.

- Indigenous-led: Indigenous peoples must be part of the process in developing the engagement plan.

- Survivor-led: Survivor voices must inform the entire engagement planning process.

- Diversity: One engagement plan will not be able to address all perspectives and all former school sites. The diversity of Indigenous peoples and Survivors across Canada requires multiple processes to ensure diverse perspectives and experiences are included in overall engagement process.

- Collaboration: Collaboration means that Indigenous peoples are equal partners and are a part of generating ideas and making decisions at every stage of engagement planning.

- Capacity Transfer: Capacity transfer goes a step beyond capacity building in that it recognizes the capacity of the various groups and their ability to work with each other.

- Structure and flexibility: While structure and plans are important, it is much more important to value flexibility as each community will have different capacity and willingness to be engaged.

- Meaningful and relevant: Ensure that engagement planning is relevant and meaningful to the groups of peoples within the community.

- Respect and reciprocity: Respect can only be achieved if there are authentic interactions. Reciprocity can only be achieved if there is accountability.

- Effective communication: An effective communication strategy is not about having a one-size fits all plan, but asking people in community how to communicate, and how they prefer to receive information.

- Trauma informed and health supports: Health supports must be present at every stage of engagement planning and execution. Importantly, health supports must continue to be available after engagement processes.

- Ceremony: Ceremony is not something that happens once through a final outcome or commemoration but should be integrated throughout the relationship building and engagement planning process.

- Protocols: Protocols are integral to building relationships in a good way with Indigenous peoples.

- Free, prior and informed consent: FPIC as a part of UNDRIP will ground the process of planning engagement with Indigenous communities.

Related work

Residential Schools Mapping Network and Interactive Mapping Tool

ISC launched an informal mapping network in September 2022 for researchers and geomatic technicians from Indigenous entities, governments and academic institutions to share information on research, tools and data on former residential school sites. The Residential Schools Mapping Network provides a forum for discussing and coordinating with researchers on topics such as Indigenous Data Sovereignty, data collection, technical innovations, and mapping approaches. For more information about the Network, please contact ISC's Residential Schools Legacy Secretariat at: IRS-ISC.PI-SAC@sac-isc.gc.ca

Using NCTR's dataset, ISC's Geomatics Unit created an interactive residential school mapping tool containing all 174 IRS sites with layer filters for reserve land, treaties, land claim agreements and historic air photos (courtesy of the National Air Photo Library at Natural Resources Canada).

ISC is committed to ensuring that the IRS Environmental Scan data will be open-source and available to researchers, communities and Survivors, with the exception of data related to burial sites that communities do not want to publicize.

National Advisory Committee on Missing Children and Burial Sites

In July 2022, CIRNAC and the NCTR announced a National Advisory Committee (NAC) to guide the implementation of Calls to Action 74-76. The NAC serves as an independent and trusted source of technical advice for communities in their efforts to locate, honour, memorialize or bring home children who died in residential schools.

The NAC brings together individuals with a wide-range of experience and expertise in areas such as Indigenous laws and cultural protocols, forensics, archeology, archival research, criminal investigations, communication and working with Survivors.

Cemetery Registry

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, through funding by CIRNAC, is leading the development of a Cemetery Register. This relates to Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Call to Action 73: "We call upon the federal government to work with churches, Aboriginal communities, and former residential school students to establish and maintain an online registry of residential school cemeteries, including, where possible, plot maps showing the location of deceased residential school children."

The development of the National Indian Residential School Online Cemeteries and Burial Sites Registry began during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Missing Children and Unmarked Burials Project. Survivors, families, and communities will decide what information they wish to share with the Government of Canada, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, and other partners to document cemeteries and burial sites.

Special Interlocutor

The Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with Indian Residential Schools will identify needed measures and make recommendations for a new federal legal framework to ensure the respectful and culturally appropriate treatment of unmarked graves and burial sites of children associated with former residential schools.

The Special Interlocutor's Interim Report (PDF), released in June 2023, highlighted the need for access to sites and affirming Indigenous Data Sovereignty. In particular, significant barriers exist for Survivors, Indigenous families, and communities to access sites to conduct ceremonies and searches, particularly where the sites are in the process of being redeveloped or are owned by corporations or private landowners. In some situations, federal, provincial, and municipal governments are not actively supporting Survivors, Indigenous families, and communities in obtaining access to the land or in protecting the sites.

Additionally, at the Standing Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples (APPA) on March 21, 2023, the Special Interlocutor called for a new legal framework to address gaps for the protection of burial sites and ensuring access to the grounds if the land is now privately held. The Office for the Special Interlocutor's Submission to UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples stated "the urgent need to document the complex history and current land ownership of burial and cemetery sites associated with Indian Residential Schools. Some sites are now privately owned, and others are endangered by land development projects." Additionally, it stated: "There are conflicts between Indigenous communities and governments over issues of jurisdictional control, ownership, and use of land."

Concluding words

The IRS Environmental Scan highlights how every former residential school site is unique, and that the status of many sites are frequently changing: buildings being used for different purpose or being demolished; properties being sold and subdivided. Sometimes there is recognition of these sites through memorials and commemorative activities. The IRS Environmental Scan dataset and ISC's Residential Schools Mapping Application will continue to be updated as new information is gathered through publicly accessible material. ISC will work with partners through the Residential Schools Mapping Network to ensure data is accessible to communities and Survivors, and available to support other related research initiatives.

ISC is exploring potential partnership(s) outside of Government of Canada to host and store the IRS Environmental Scan data and coordinate future research and collection of new data including potential information gained through site visits or inputs received from communities. A data integrity protocol based upon Indigenous Data Sovereignty principles is being developed with partners, including through the Residential Schools Mapping Network and other experts.

Annex A: Details on Land Ownership and Building Condition

| Region | # of IRS | Total Sites | On Reserve | Off-Reserve | % Off-Reserve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | 18 | 22 | 15 | 7 | 32% |

| AB | 25 | 33 | 21 | 12 | 36% |

| SK | 18 | 25 | 18 | 7 | 28% |

| MB | 14 | 23 | 12 | 11 | 48% |

| ON | 18 | 24 | 8 | 16 | 67% |

| QC | 12 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 83% |

| ATL | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 100% |

| North | 34 | 34 | 0 | 34 | 100% |

| TOTALS | 140 | 174 | 76 | 98 | 56% |

| Province/Territory | IRS Name | Site | Number of buildings still in use | Current Building Use | On reserve/off-reserve, North |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | Lac la Biche | Main Site | 1 | Historical centre | Off-reserve |

| AB | St. Paul's (Blood) | First Site | 1 | Treatment centre | Off-reserve |

| AB | Grouard (St. Bernard's) | Main Site | 1 | North Lakes College | Off-reserve |

| AB | Blue Quills (Sacred Heart) | Second Site | 1 | University Blue Quills University nuhelot'ine thaiyots'i nistameyimâkanak |

On reserve |

| AB | Ermineskin (Hobbema) | Main Site | 2 | Gym and kindergarten | On reserve |

| AB | Old Sun (Blackfoot) | Second Site | 1 | Old Sun College | On reserve |

| AB | St. Paul's (Blood) | Second Site | 1 (maybe more) | Residential housing for Red Crow College | On reserve |

| BC | Alberni | Main Site | 4 | Office space, gymnasium, band administration | On reserve |

| BC | Cariboo (St. Joseph's, William's Lake) | Main Site | 3 (could be more, unsure of number of residences) | Recreational facility and residences | Off-reserve |

| BC | Christie (Tofino, Clayoquot, Kakawis) | First Site | 1 | Tourism operation | Off-reserve |

| BC | Christie (Tofino) | Second Site | 2 | Tin-Wis Hotel (Best Western), maintenance shop | On reserve |

| BC | Cranbrook (St. Eugene's, Kootenay) | Main Site | 1 (maybe more) | St. Eugene Mission Resort | On reserve |

| BC | Kamloops (St. Louis) | Main Site | 4 | Chief Louis Centre (multi-purpose space including Tk'emlúps te Secwe̓pemc program delivery, office space for various Indigenous entities). Annex (Council Chambers, language and culture programs, museum), Former gymnasium (Moccasin Square Gardens community centre) and storage | On reserve |

| BC | St. Mary's (Mission) | Main Site | 1 | Day care and community use | Off-reserve |

| BC | St. Mary's (Mission) | Main Site | 1 (maybe more) | Heritage site and park | On reserve |

| MB | Assiniboia (Winnipeg) | Main Site | 1 | Canadian Centre for Child Protection and RCMP | Off-reserve |

| MB | Dauphin (replaced McKay) | Second Site | 1 (could be more than one building) | Community services (including affordable housing) | Off-reserve |

| MB | Portage la Prairie | Main Site | 1 | Long Plain's National Residential Schools Museum and administration space for First Nations policing | On reserve |

| NT | Bompas Hall (Koe Go Cho, Fort Simpson) | Main Site | 1 | Bompas Elementary School | North |

| NT | Breynat Hall (Fort Smith Hostel) | Main Site | 1 | Thebacha Campus, Aurora College | North |

| NT | Grandin College (Fort Smith) | Main Site | 1 | Part of Paul W. Kaesar high School Complex | North |

| NU | Federal Hostel at Baker Lake (Qamani'tuaq) | Main Site | 1 | North | |

| NU | Federal Hostel at Pond Inlet (Mittimatalik) | Main Site | At least 1 | Ulaajuk Elementary School | North |

| NU | Kivalliq Hall | Main Site | 1 | Nunavut Arctic College | North |

| ON | Fort Frances (Coochiching, St. Margaret's) | Main Site | 1 | Office space | On reserve |

| ON | Mohawk Institute (Mechanic's Institute) | Main Site | 1 | Woodland Cultural Centre | On reserve |

| ON | Shingwauk (Wawanosh) | Main Site | 1 | Algoma University | Off-reserve |

| QC | La Tuque | Main Site | 3 | Day care and Auberge la Residence | Off-reserve |

| QC | Pointe Bleue | Main Site | 2 | Kassinu Mamu High School, dormitory | On reserve |

| QC | Sept-Iles (Maliotenam) | Main Site | At least 2 | Health centre, storage space for Innu Nikamu festival | On reserve |

| SK | Lebret (Qu'Appelle, Whitecalf, St. Paul's High School) | Main Site | 3 | Gymnasium, arena and residence | On reserve |

| SK | Marieval (Cowessess, Crooked Lake) | Main Site | At least 2 | Cultural centre | On reserve |

| SK | Prince Albert (Onion Lake, St. Alban's, All Saints, St. Barnabus, Lac La Ronge) | Last Site | At least 2 | Housing, services, offices for the Opawakoscikan community | On reserve |

| YT | Carcross (Choutla) | Main Site | 3 | Teacherages converted to single family dwellings | North |

Under 'site,' it is specified whether the buildings currently being used are located on. This includes:

Based on available information as of December 2023. |

|||||

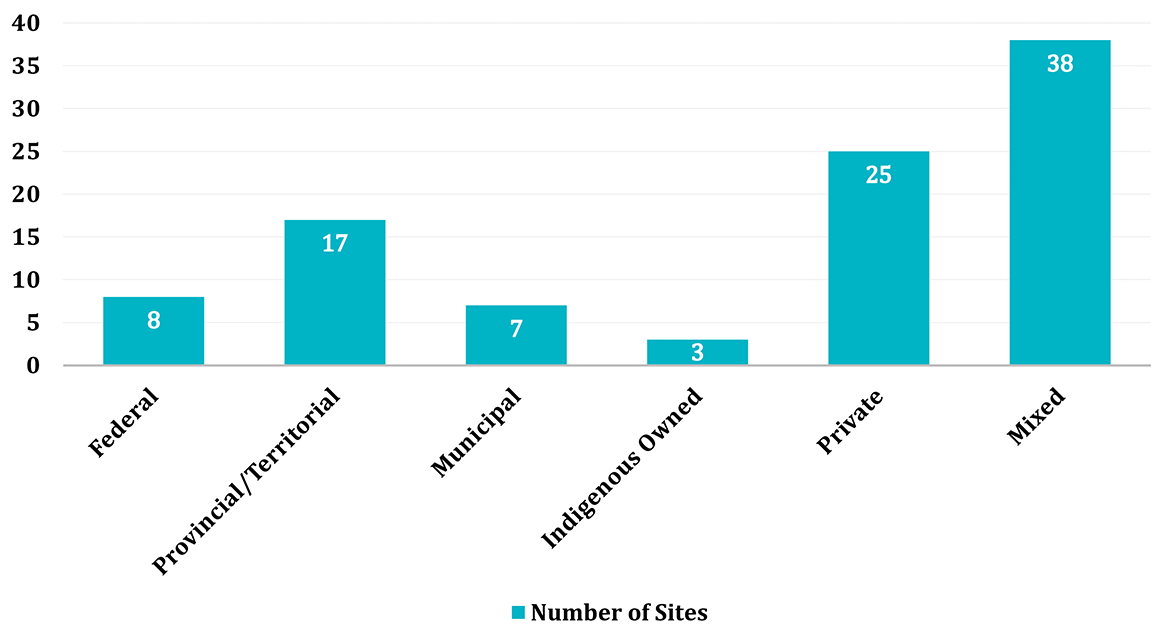

Text alternative for Graph 1: Ownership of land for the 98 school sites that are located off-reserve and the North

The graph above displays the land tenure for the 98 school sites located off-reserve and in the North. There are 6 federally owned sites, 17 provincially/territorially owned sites, 7 municipality owned sites, 3 Indigenous owned sites, 25 privately owned sites, and 40 mixed ownership sites.

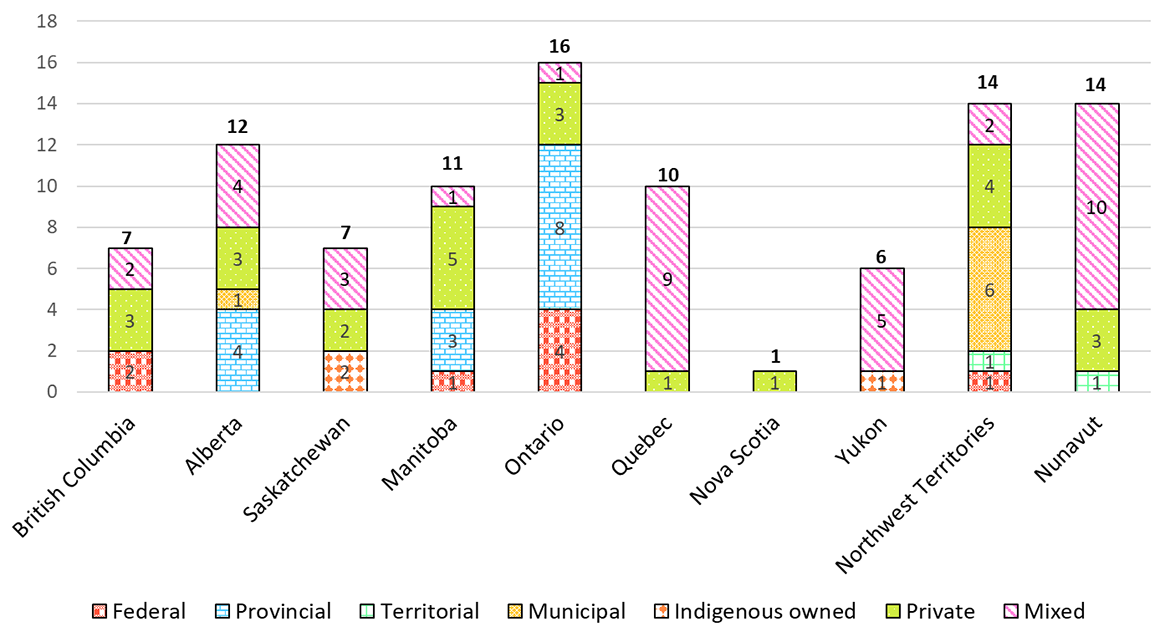

Text alternative for Graph 2: Land ownership of 98 school sites off-reserve & in the North by province and territory

This graph shows the land ownership or tenure for the 98 IRS sites located off-reserve and in the North, by province and territory.

- British Columbia has 7 total sites in total: 2 federal, 3 private, 2 mixed

- Alberta has 12 total sites in total: 4 provincial, 1 municipal, 3 private, 4 mixed

- Saskatchewan has 7 total sites in total: 2 Indigenous owned, 2 private, 3 mixed

- Manitoba has 11 total sites in total: 1 federal, 3 provincial, 5 private, 1 mixed

- Ontario has 16 total sites in total: 3 federal, 8 provincial, 3 private, 2 mixed

- Quebec has 10 total sites in total: 1 private, 9 mixed

- Nova Scotia has 1 site in total: 1 private

- Yukon has 6 total sites in total: 1 Indigenous owned, 5 mixed

- Northwest Territories has 14 total sites in total: 1 territorial, 6 municipal, 4 private, 3 mixed

- Nunavut has 14 total sites in total: 1 territorial, 3 private, 10 mixed

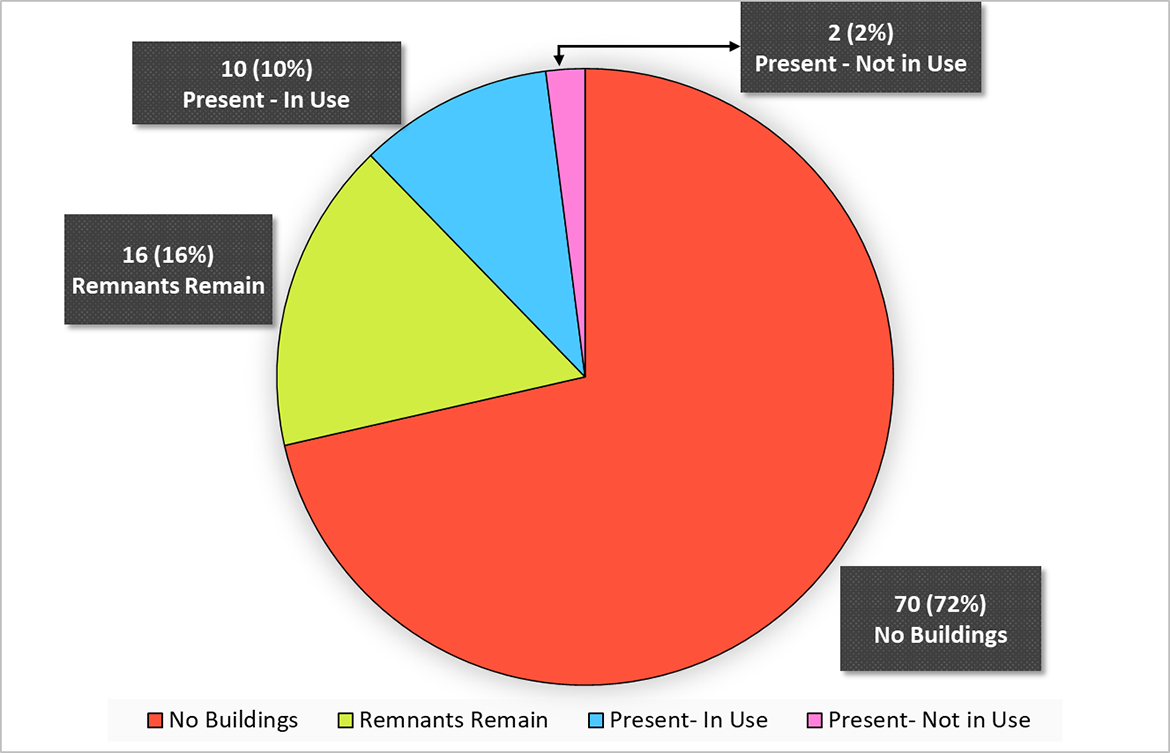

Text alternative for Graph 3: Status of the main school buildings on the 98 school sites located off-reserve and in the North

Graph 3 shows a pie chart breakdown of the status of main school buildings located on the 98 residential school sites located off reserve and in the North. Of these school buildings, 70 sites, or 72%, have no main buildings. Sixteen sites, or 16%, have remnants of main buildings. Ten sites, or 10% of sites, have a main building present that is being used. And, 2 sites, or 2%, have a main building present that is not in use.

Text alternative for Graph 4: Status of the ancillary buildings on the 98 school sites located off-reserve and in the North

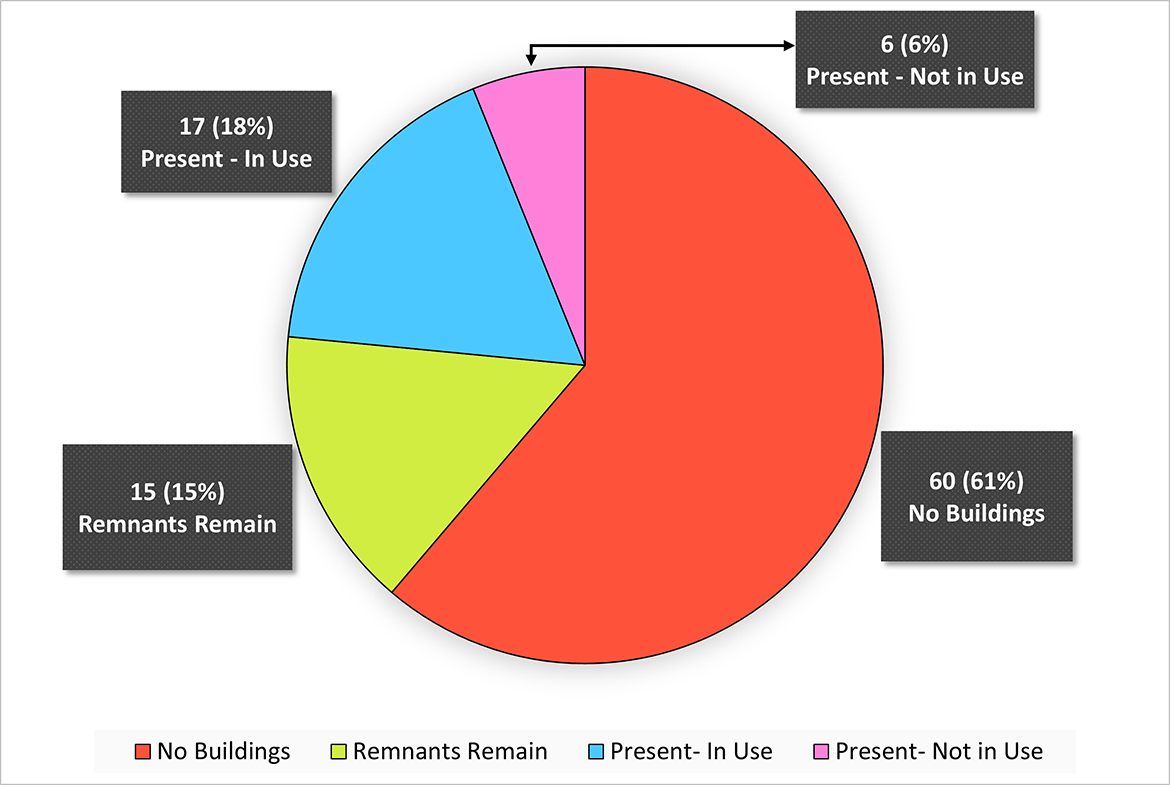

Graph 4 shows a pie chart breakdown of the status of ancillary school buildings located on the 98 residential school sites located off-reserve and in the North. Of these school buildings, 60 sites, or 61%, have no ancillary buildings. Seventeen sites, or 18%, have an ancillary building present that is being used. Fifteen sites, or 15%, have remnants of past ancillary buildings. Finally, 6 sites, or 6%, have an ancillary building present that is not in use.

Text alternative for Graph 5: Building status of the main school buildings located on the 76 residential school sites on reserve

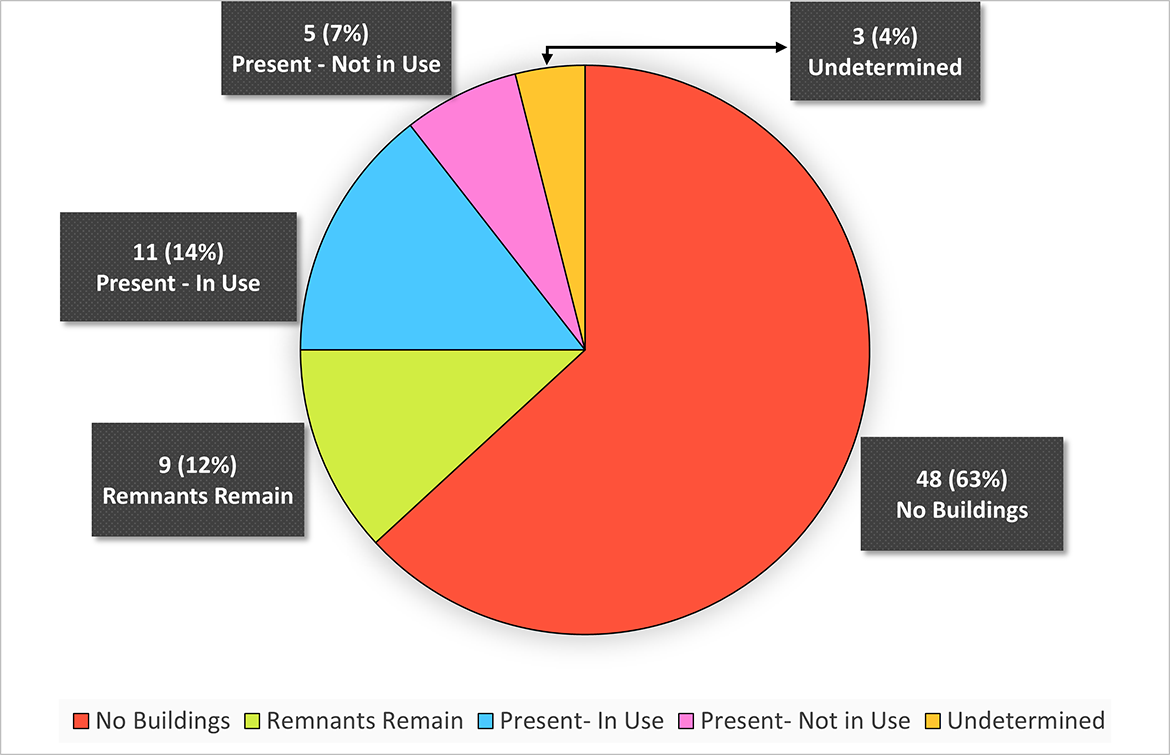

Graph 5 shows a pie chart breakdown of the status of the main school buildings on the 76 residential school sites located on reserve. Of these school buildings, 48 sites have no buildings, making up 63%. Eleven sites, making up 14% of sites, have a building present that is being used. Nine sites, making up 12%, have remnants of past buildings. Five sites have a building present, or 7%, that is not in use. Finally, 3 sites, or 4% of the total, have a undetermined use or status.

Text alternative for Graph 6: Building status of the ancillary buildings located on the 76 residential school sites on reserve

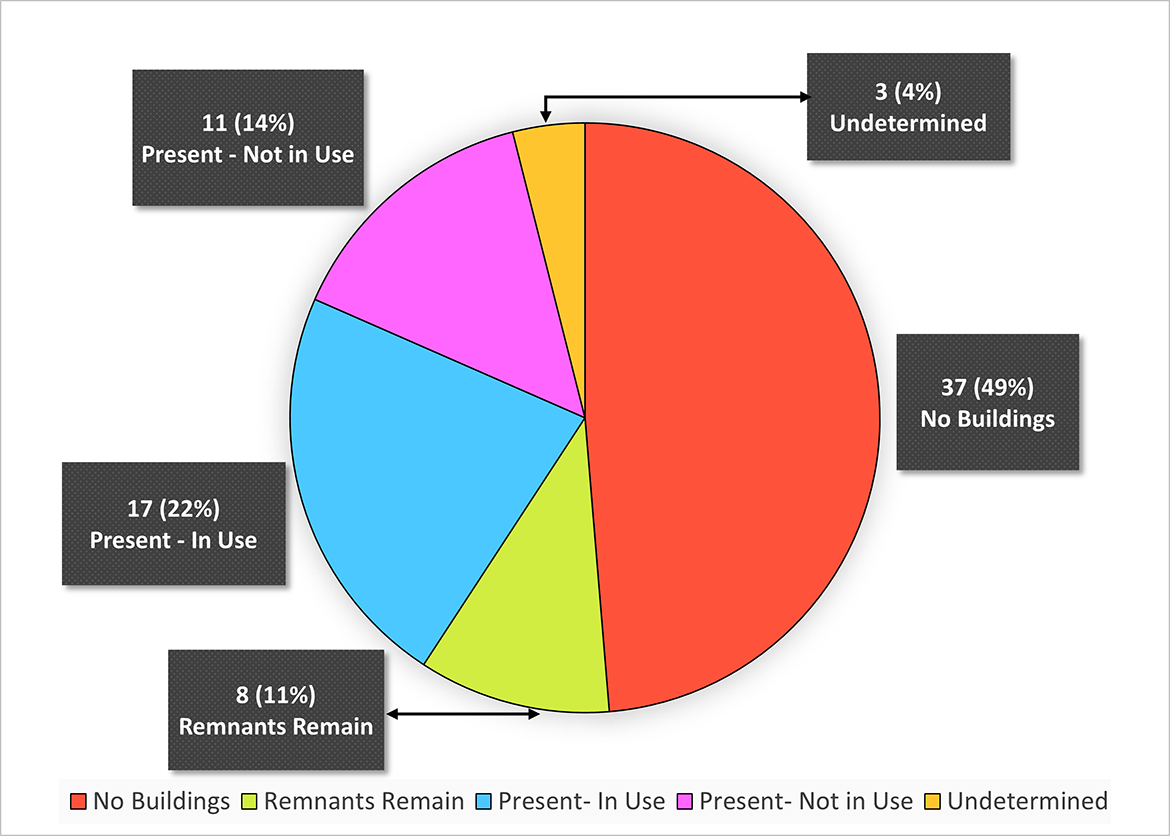

Graph 6 shows a pie chart of the status of ancillary school buildings on the 76 residential school sites located on reserve. Of these school buildings, 37 sites, making up 49%, have no buildings. Seventeen sites, or 22% of sites, have a building present that is being used. Eleven sites, or 14% of the total, have a building present that is not in use. Eight sites, making up 11%, have remnants of past buildings. Finally, 3 sites, or 4% of the total, have a undetermined use or status.

Annex B: References and other information sources

Public sites

- Indigenous Services Canada - Indian Residential School Interactive Map

- Government of Canada - Directory of Federal Real Property | Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (tbs-sct.gc.ca)

- Crown Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada - ISC & CIRNAC Map Room

- Indian Land Registry System - AANDC ILRS/AADNC ILRS - Public Interface

- National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation - Residential School History

- Natural Resources Canada - Natural Resources Canada - Maps, Tools & Publications

- Algoma University - Algoma University Archives

- University of British Columbia - Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre - Collections

- University of Regina - History of Indian Residential Schools in Saskatchewan

- Williams Lake First Nation - St. Joseph's Mission School | Williams Lake First Nation (wlfn.ca)

Provincial and territorial land and property registries

- Manitoba - Manitoba Land Settlement Agreements Including TLE

- Alberta - Alberta Registries - SPIN2HOME

- Alberta - Resource guide for researching and recognizing residential school sites

- Saskatchewan - Saskatchewan Provincial Archives

- Saskatchewan - Sask Interactive Mapping

- Yukon - YUKON - GeoSpacial Map

- Ontario - OnLand Property Search

- Quebec - Registre foncier du Québec en ligne (gouv.qc.ca) (not available in English)

Residential Schools Mapping initiatives

A number of mapping initiatives involving former Indian residential schools sites are available online, including: