Evaluation of the Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Business Development Program

PDF Version (785 KB, 55 pages)

Table of contents

- List of abbreviations and acronyms

- Executive summary

- Management response and action plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Program description

- 3. Evaluation methodology

- 4.0 Key findings

- 5. Conclusions

- 6. Recommendations

- Appendix A: IEBD logic model and budget

- Appendix B: Evaluation questions

- Appendix C: Detailed participant Information

List of abbreviations and acronyms

- ABO

- Access to Business Opportunities

- ATC

- Access to Capital

- COVID-19

- Coronavirus Disease

- IEBD

- Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Business Development

- IFI

- Indigenous Financial Institution

- ISC

- Indigenous Services Canada

- MCC

- Métis Capital Corporation

- NACCA

- National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association

- PSIB

- Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business

- 2SLGBTQI+

- Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex Plus

Executive summary

As part of Indigenous Services Canada's commitments under the Treasury Board Financial Administration Act (1985), Policy on Results (2016) and Directive on Results (2016), from 2021-2023 ISC Evaluation undertook an evaluation of the Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Business Development (IEBD) Program (in this document referred to as "the Program"), covering the five-year period from 2015-16 to 2020-21. This IEBD Program consists of three complementary sub-programs that support Indigenous entrepreneurs in Canada: Access to Capital (ATC), Access to Business Opportunities (ABO) and Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business (PSIB) programs. IEBD Program spending averaged approximately $47 million per year over the period of the evaluation.

This evaluation assesses the Programs' relevance, effectiveness and efficiency, as per the definition of "Evaluation" under the Policy on Results:

- Relevance: The extent to which the programs address and are responsive to the needs of First Nations, Inuit and Métis business owners and entrepreneurs. Also, the extent to which programs align with federal government priorities and responsibilities.

- Effectiveness: The extent to which programs achieve their expected outcomes and objectives, as identified in the logic model (Appendix A).

- Efficiency: The extent to which resources (e.g. funding) are used to produce program outputs or outcomes.

In addition, this evaluation also assesses the Program's impacts on families and children, the extent to which the programs advance self-determination and service transfer, and the Program's responsiveness to business needs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The evaluation collected data from four key lines of evidence: a literature review of relevant program documents, performance data and other publications; individual interviews with 45 key informants; a survey of 441 Indigenous entrepreneurs across Canada; and a series of discussion circles with representatives of Indigenous Financial Institutions (IFIs), MCCs, and PSIB coordinators.

Program strengths

The evaluation found that the IEBD Program remains relevant to both Indigenous and federal priorities, including a priority to advance Indigenous self-determination. The Program helped remove barriers to Indigenous People seeking business capital and supports, and is meeting the intended outcomes of sustaining the network of Indigenous lending institutions, creating and expanding Indigenous businesses, and creating or maintaining jobs through lending.

During the evaluation period, the administration and delivery of the ATC program was transferred to Indigenous partners representing the network of Indigenous-owned lending institutions (IFIs and MCCs), which overall went well and is widely supported by Indigenous partners. The importance of continued funding to support the ATC program is also underscored by findings that Indigenous entrepreneurs feel a stronger and more personal relationship with IFIs and MCCs than with mainstream lending institutions. In addition, the program has had positive impacts for individuals, families and communities, and the lending system moved quickly to respond to the needs of Indigenous entrepreneurs and businesses amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Program limitations

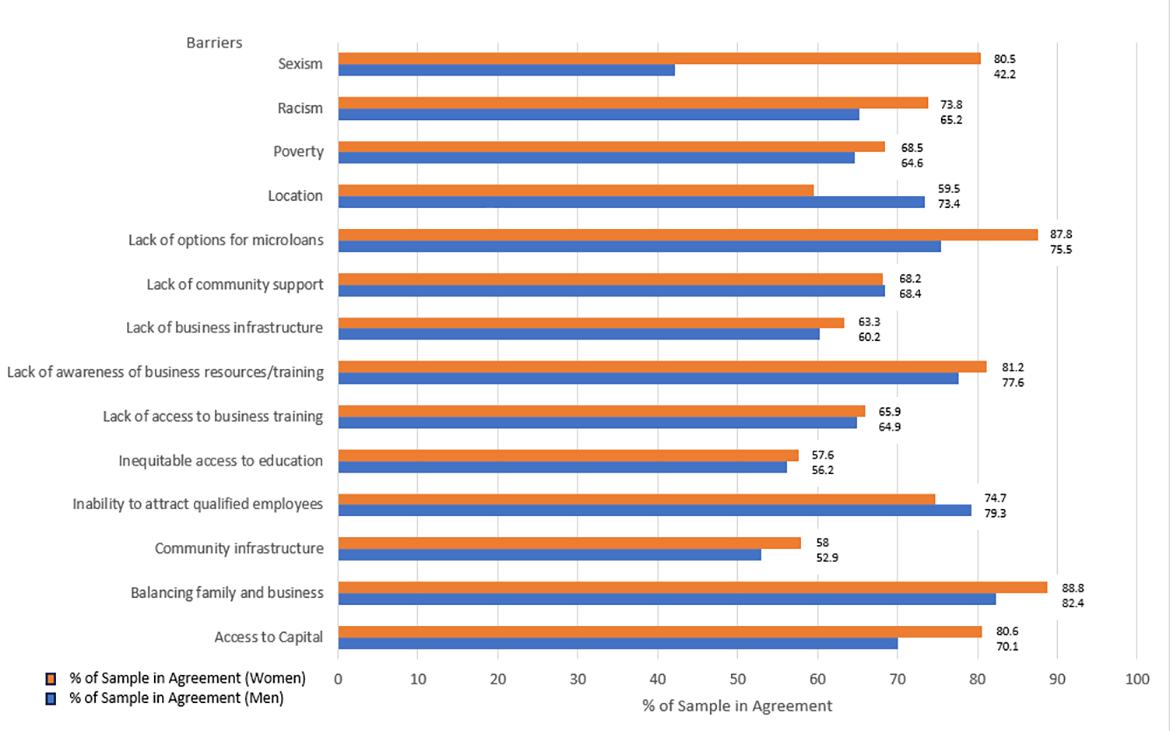

There continue to be barriers to Indigenous entrepreneurship and business that are not addressed by the current scope of the program. The evaluation found that the program's investment in the Indigenous lending system is not sufficient to meet current and anticipated future levels of demand for loans and business supports, given the anticipated growth in the Indigenous population. The evaluation also found that there is an ongoing need for targeted investments in pre- and post-care to facilitate success across all stages of business development. As well, a siloed approach to funding across the IEBD sub-programs creates challenges for entrepreneurs, particularly when navigating various supports and requirements. Also, the transfer of the ATC program is currently limited to the delivery of contributions, and further work is required to fully transfer the suite of IEBD programs.

Although efforts have been made to improve the inclusivity and reach of programs across distinctions, gender and age groups, more work is needed to reach and monitor equity in access. The current logic model and inconsistent program data do not reflect outcomes relevant to Indigenous entrepreneurs, nor do they allow for the assessment of program impacts. An updated performance measurement framework is required in order to reflect outcomes relevant to Indigenous entrepreneurs and key program partners. The evaluation also found that the Indigenous lending system does not have sufficient funding under the program to meet current and anticipated future levels of demand. This said, the lending system moved quickly to respond to the needs of Indigenous entrepreneurs and businesses amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

Recommendations

It is therefore recommended that ISC:

- Engage First Nation, Inuit and Métis partners to explore options to transfer the full IEBD program, including the Indigenous Business Directory and the ABO stream of funding. This includes a recommendation to:

- Work with First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners to fully transfer the ATC program, including the design, delivery, eligibility, and reporting of results on a distinctions basis.

- Engage First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners of all program streams to develop an approach to further reduce barriers to entrepreneurship, including by broadening program access for Indigenous Peoples who are harder to reach and/or face exacerbated barriers to the pursuit of entrepreneurship. This includes recommendations to:

- Engage First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners of all program streams to consistently support pre- and post-care for Indigenous entrepreneurs;

- Explore and ensure that the federal procurement process is equally accessible to First Nations, Inuit and Métis businesses; and

- Perform ongoing monitoring of the adjustments resulting from the modernization initiative to ensure that adjustments prove effective.

- Co-develop with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples a new program logic model and performance measurement framework that contains broader outcome measurements supported by Indigenous partners. This includes a recommendation to:

- Collaborate with internal and external partners to expand and employ Gender-Based Analysis Plus to their data collection, and sustainable targeted approaches meeting the needs of diverse groups.

- Explore options to increase the funding envelope under IEBD, allowing for greater reach, impact and transparency. This includes recommendations to:

- Work with ATC partners to explore long-term funding mechanisms that will better support the sustainability of IFIs and their ability to deliver developmental lending; and

- Work with First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners to explore targeted approaches and better leverage existing approaches to support IFIs/MCCs in retaining skilled employees.

- Standardize the PSIB Coordinator role and provide ongoing centralized support to the PSIB Coordinator Network. This support may include ensuring Coordinators have sufficient onboarding, training, and capacity to perform the functions of this role, and that there is a consistent and transparent line of communication between ISC and the Network of Coordinators.

Management response and action plan

Evaluation Title: Evaluation of the Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Business Development Program

Overall management response

Overview

- This evaluation examines the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of the Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Business Development (IEBD) program, covering a five-year program cycle from 2015-16 to 2020-21.

- The IEBD program is designed to support business and economic development efforts of Indigenous entrepreneurs and communities.

- The IEBD program is comprised of three program areas that support Indigenous entrepreneurs in Canada:

- Aboriginal Entrepreneurship Program – Access to Capital (AEP-ATC) provides funding to establish, expand and diversify the network of Indigenous Financial Institutions (IFIs) and Métis Capital Corporations (MCCs) providing developmental capital to Indigenous entrepreneurs, thereby enhancing access to capital for Indigenous entrepreneurs across Canada.

- Aboriginal Entrepreneurship Program – Access to Business Opportunities (AEP-ABO) provides funding to promote a culture of entrepreneurship, improve access to business opportunities and to enhance the capacity of Indigenous businesses.

- The Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business (PSIB) is a program that supports Indigenous businesses through access to specific federal procurement bidding opportunities.

- The recommendations stemming from this evaluation will guide upcoming policy, planning, and delivery efforts. This includes recommendations to address barriers to entrepreneurship and enhance program access for harder-to-reach Indigenous Peoples; explore options for program expansion and transfer of the full IEBD program; and enhance data collection, monitoring, and transparency. Wherever possible, these efforts will be made in collaboration across program areas, with Indigenous partners and other relevant internal and external partners.

- The AEP-ATC stream has become an important source of capital for Indigenous business development, and over its thirty-year history it has made significant contributions to the Canadian economy. However, at its current levels of funding it's struggling to support the ever-increasing loan demand of Indigenous businesses, as well as the deployment of the newly launched Indigenous Growth Fund. An increase in funding for the ATC stream is critical to ensure the continued availability to affordable equity capital for Indigenous businesses and entrepreneurs.

- The AEP-ABO stream has broad terms and conditions, making it one of the more flexible programs to advance Indigenous economic development. However, the Program has limited funding and therefore focuses on supporting national-level projects to maximize the Program's impact. A significant increase in funding for the ABO stream would enable the successful implementation for many of the recommendations outlined in the Evaluation.

- The Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business (PSIB) is a program applied by all departments when conducting federal procurements. The program is in place to ensure that specific federal tenders are limited to bidding among businesses listed on the Indigenous Business Directory or Modern Treaty business lists. PSIB is a key element to increasing the representation of Indigenous businesses in federal procurement and plays a critical role in federal departments reaching the mandatory minimum 5% target.

Assurance

- The Action Plan presents appropriate and realistic measures to address the evaluation's recommendations, as well as timelines for initiating and completing the action. The Action Plan presents three sets of measures: those that are the responsibility of AEP-ABO, those that are the responsibility of PSIB, and those that are the responsibility of AEP-ATC.

Action plan matrix

Aboriginal Entrepreneurship Program – Access to Business Opportunities

Sector: Lands and Economic Development Sector

Program: Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Business Development Program

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Start and Completion Dates | Action Item Context/Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Indigenous Services Canada is recommended to engage First Nation, Métis and Inuit Partners to explore options to transfer the full IEBD program, including the Indigenous Business Directory and the ABO stream of funding. This includes a recommendation to: 1A) Work with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis partners to fully transfer the Access to Capital program, including the design, delivery, eligibility, and reporting of results on a distinctions basis. |

We do concur Recommendation 1: Starting in April 2024, in collaboration with other program areas (i.e., PSIB, ATC, etc.), AEP-ABO will engage with national Indigenous organizations (i.e., NWAC, Métis National Council, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, etc.), as well as national Indigenous economic development organizations (i.e., NACCA, CCAB, CANDO, etc.) to co-develop the following: determine the activities/functions that should be transferred and identify any residual activities that will remain with ISC; a recommended approach to the service transfer (i.e., distinctions-based, etc.); identify potential delivery partner(s); and identify the additional funding and program enhancements required to enable the service transfer of the AEP-ABO. Sub-Recommendation: 1A) N/A |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: April 2024 Completion: 2027-2028 |

Status: Implementation did not commence Update/Rationale: This action item is currently in the development and planning phase, with a scheduled implementation date set for April 2024. As of: September 2023 |

| 2) Engage First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners of all program streams to develop an approach to further reduce barriers to entrepreneurship, including by broadening program access for Indigenous Peoples who are harder to reach and/or face exacerbated barriers to the pursuit of entrepreneurship. This includes recommendations to: 2A) Engage First Nation, Inuit, and Métis partners of all program streams to consistently support pre- and post-care for Indigenous entrepreneurs; 2B) Explore and ensure that the federal procurement process is equally accessible to First Nation, Inuit, and Métis businesses; and 2C) Perform ongoing monitoring of the adjustments resulting from the modernization initiative to ensure that adjustments prove effective. |

We do concur. Recommendation 2: Starting in April 2024, in collaboration with other program areas (i.e., PSIB, ATC, etc.), AEP-ABO will engage with national Indigenous organizations (i.e., NWAC, Métis National Council, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, etc.), as well as national Indigenous economic development organizations (i.e., NACCA, CCAB, CANDO, etc.) to determine program enhancements that can be implemented immediately, and those that will require additional funding, to: broaden access to the AEP-ABO; and identify which barriers to entrepreneurship can be addressed through the AEP-ABO and accordingly determine effective approaches to reducing/eliminating these barriers. |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: April 2024 Completion: 2027-2028 |

Status: Implementation did not commence Update/Rationale: This action item is currently in the development and planning phase, with a scheduled implementation date set for April 2024. As of: September 2023 |

| We do concur. Sub-Recommendation: 2A) Starting in April 2024, in collaboration with other program areas (i.e., PSIB, ATC, etc.), AEP-ABO will engage with previous funding recipients, national Indigenous organizations (i.e. NWAC, Métis National Council, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, etc.), as well as national Indigenous economic development organizations (i.e., NACCA, CCAB, CANDO, etc.) to determine supports required in pre- and post-care for Indigenous entrepreneurs and determine which can be implemented immediately and those that require additional funding to implement. 2B) N/A 2C) N/A |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: April 2024 Completion: 2027-2028 |

Status: Implementation did not commence Update/Rationale: This action item is currently in the development and planning phase, with a scheduled implementation date set for April 2024. As of: September 2023 |

|

| 3) Co-develop with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples a new program logic model and performance measurement framework that contains broader outcome measurements supported by Indigenous partners. This includes a recommendation to: 3A) Collaborate with internal and external partners to expand and employ Gender-Based Analysis Plus to their data collection, and sustainable targeted approaches meeting the needs of diverse groups. |

We do concur. Recommendation 3: Starting in April 2024, in collaboration with other program areas (i.e., PSIB, ATC, etc.), AEP-ABO will engage with national Indigenous organizations (i.e., NWAC, Métis National Council, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, etc.), as well as national Indigenous economic development organizations (i.e., NACCA, CCAB, CANDO, etc.) to co-develop short, intermediate, and long-term outcomes that align with First Nations, Métis, an Inuit economic development priorities and incorporate these into a program logic model that can be used for planning and evaluation of the program (i.e., guide program activities, monitor progress, assess program effectiveness, etc.). |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: April 2024 Completion: 2027-2028 |

Status: Implementation did not commence Update/Rationale: The action item is currently in the development and planning phase, with a scheduled implementation date set for April 2024. As of: September 2023 |

| We do concur. Sub-Recommendation: 3A) Starting in April 2024, the AEP-ABO will engage with subject matter experts within ISC, as well as work in collaboration with other program areas (i.e., PSIB, ATC, etc.), AEP-ABO to engage with national Indigenous organizations (i.e., NWAC, Métis National Council, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, etc.), as well as national Indigenous economic development organizations (i.e., NACCA, CCAB, CANDO, etc.) to review AEP-ABO's data collection structure and identify improvements required in order to employ GBA Plus to the Program's data collection and analysis approach. |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: April 2024 Completion: 2027-2028 |

Status: Implementation did not commence Update/Rationale: The action item is currently in the development and planning phase, with a scheduled implementation date set for April 2024. As of: September 2023 |

|

| 4) Explore options to increase the funding envelope under IEBD, allowing for greater reach, impact and transparency. This includes recommendations to: 4A) Work with ATC partners to explore long-term funding mechanisms that will better support the sustainability of IFIs and their ability to deliver developmental lending; and 4B) Work with First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners to explore targeted approaches and better leverage existing approaches to support IFIs/MCCs in retaining skilled employees. |

We do concur. Recommendation 4: Based on the findings of the Program Evaluation, the AEP-ABO will take immediate steps to increase the transparency of the Program. Starting in April 2024, in collaboration with other program areas (i.e., PSIB, ATC, etc.), AEP-ABO will engage with national Indigenous organizations (i.e. NWAC, Métis National Council, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, etc.), as well as national Indigenous economic development organizations (i.e., NACCA, CCAB, CANDO, etc.) to determine the additional funding required for the AEP-ABO stream that would enable greater reach and increase transparency. Sub-Recommendation: 4A) N/A 4B) N/A |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: May 2023 Completion: 2027-2028 |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: The AEP-ABO is currently updating the Program's Management Control Framework and, as part of that process, identifying areas to enable greater transparency and developing processes to implement those changes. As of: September 2023 |

| 5) Standardize the PSIB Coordinator role and provide ongoing centralized support to the PSIB Coordinator Network. This support may include ensuring Coordinators have sufficient onboarding, training, and capacity to perform the functions of this role, and that there is a consistent and transparent line of communication between ISC and the Network of Coordinators. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business

Sector: Lands and Economic Development Sector

Program: Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Business Development Program

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title/Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates | Action Item Context/Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Indigenous Services Canada is recommended to engage First Nation, Métis and Inuit Partners to explore options to transfer the full IEBD program, including the Indigenous Business Director and the ABO stream of funding. This includes a recommendation to: 1A) Work with First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners to fully transfer the Access to Capital program, including the design, delivery, eligibility, and reporting of results on a distinctions basis. |

We do concur. Recommendation 1: Continue engagements with national and regional Indigenous economic development organizations, modern treaty land claim agreement holders and Indigenous businesses to help inform how the Indigenous Business Directory could be transferred to Indigenous partners and the level of funding required to enable the service transfer. Sub-Recommendation: 1A) N/A |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: Fall 2023 Completion: Spring 2025 – Return to Cabinet with recommendations for Transformative Indigenous Procurement Strategy. |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: Starting in 2019, Indigenous Services Canada conducted engagements with partners, which informed the changes to the Procurement Strategy to Indigenous Business that were announced in 2021. Moreover, as part of that announcement was the creation of Transformative Indigenous Procurement Strategy and commitment to continue engagement and consultations with Indigenous partners to co-develop a more transformative Indigenous procurement Strategy. Indigenous Services Canada is currently building relationships and beginning engagements and consultations this Fall 2023 which included Indigenous Services Canada discussions about addressing barriers and how they are addressed in a forthcoming strategy (due 2025); including the review of opportunities for service transfer of IBD to one or more Indigenous Partners. Note: Engagement and consultation activities started in Winter 2022 and are expected to end in early Summer 2024. Co-development should start in 2024, with a proposed return to Cabinet with a transformed Indigenous procurement strategy in Spring 2025. Some partners maybe ready at different points of this timeline. As of: September 2023 |

| 2) Engage First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners of all program streams to develop an approach to further reduce barriers to entrepreneurship, including by broadening program access for Indigenous Peoples who are harder to reach and/or face exacerbated barriers to the pursuit of entrepreneurship. This includes recommendations to: 2A) Engage First Nation, Inuit, and Métis partners of all program streams to consistently support pre- and post-care for Indigenous entrepreneurs; 2B) Explore and ensure that the federal procurement process is equally accessible to First Nation, Inuit, and Métis businesses; and 2C) Perform ongoing monitoring of the adjustments resulting from the modernization initiative to ensure that adjustments prove effective. |

We do concur. Recommendation 2: Conduct engagement sessions with national and regional Indigenous economic development organizations, modern treaty holders, Indigenous businesses and other federal organizations. Sub-Recommendation: 2A) N/A |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: Summer 2019 Completion: Summer 2024 |

Status: Partially Implemented Starting in 2019, Indigenous Services Canada conducted engagements with partners, which informed the changes to the Procurement Strategy to Indigenous Business that were announced in 2021. Moreover, as part of that announcement was the creation of Transformative Indigenous Procurement Strategy and commitment to continue engagement and consultations with Indigenous partners to co-develop a more transformative Indigenous procurement Strategy. Indigenous Services Canada is currently building relationships and beginning engagements and consultations this Fall 2023 which includes Indigenous Services Canada discussions about addressing barriers and how they are addressed in a forthcoming strategy (due 2025); Note: Engagement and consultation activities started in Winter 2022 and are expected to end in early Summer 2024. Co-development should start in 2024, with a proposed return to Cabinet with a transformed Indigenous procurement strategy in Spring 2025. Some partners maybe ready at different points of this timeline. As of: September 2023 |

| We do concur. Sub-Recommendation: 2B) Work collaboratively with PSPC and TBS to reduce barriers for Indigenous entrepreneurs accessing federal procurement opportunities. |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: Summer 2023 Completion: Ongoing |

Status: Partially Implemented In Summer 2023, the PSIB program was absorbed into the Transformative Indigenous Procurement Strategy Directorate (TIPS). Since inception, December 2021, TIPS has been collaboratively working with PSPC and TBS in the advancement of the TIPS Mandate which is shared with both PSPC and TBS. TIPS has been supporting PSPC PAC by partnering in the planning and administration of some business information sessions for Indigenous entrepreneurs accessing federal procurement opportunities (starting December 2022). As of: September 2023 |

|

| We do concur. Sub-Recommendation: 2C) Conduct engagement sessions with national and regional Indigenous economic development organizations, modern treaty rights-holders, Indigenous businesses, and other federal organizations to determine what is effective and useful information that will not only assist Indigenous businesses, but easily monitor Departmental performance against established initiatives. |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: January 2024 Completion: Spring 2025 – Return to Cabinet with recommendations for Transformative Indigenous Procurement Strategy. |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: Starting in 2019, Indigenous Services Canada conducted engagements with partners, which informed the changes to the Procurement Strategy to Indigenous Business that were announced in 2021. Moreover, as part of that announcement was the creation of Transformative Indigenous Procurement Strategy and commitment to continue engagement and consultations with Indigenous partners to co-develop a more transformative Indigenous procurement Strategy. Additionally, TIPS is responsible for monitoring Departmental performance against the establishment a mandatory minimum target of 5% of the total value of contracts be awarded to Indigenous businesses for all Government Departments. September 2023 is when the first performance reports are to be submitted and ISC will release an annual report in Spring 2024. As part of the engagement and Consultation activities, TIPS will include discussions about improvements to the minimum target of 5% data as well as other data measures that can better showcase Government procurement data but also best demonstrate efficacy of initiatives. Indigenous Services Canada is working to build reporting to monitor implementation of other procurement initiatives like the 5% as part of our engagement, we are consulting with Indigenous partners on data and reporting strategies, and will build on this learning to ensure any future programs or policies include regular performance measurement and a data strategy. As of: September 2023. |

|

| 3) Co-develop with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples a new program logic model and performance measurement framework that contains broader outcome measurements supported by Indigenous partners. This includes a recommendation to: 3A) Collaborate with internal and external partners to expand and employ Gender-Based Analysis Plus to their data collection, and sustainable targeted approaches meeting the needs of diverse groups. |

We do concur. Recommendation 3: Conduct engagement sessions with national and regional Indigenous economic development organizations, modern treaty rights-holders, Indigenous businesses, and other federal organizations. |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: 2022 and is ongoing Completion: Spring 2025 – Return to Cabinet with recommendations for Transformative Indigenous Procurement Strategy. |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: Indigenous Services Canada is currently building relationships and beginning engagements and consultations this Fall 2023 which included Indigenous Services Canada discussions about addressing barriers that can be addressed and how they are addressed in a forthcoming strategy (due 2025); as part of ongoing procurement transformation we expect to build co-development tables in 2024-25 with Indigenous partners. Discussions in the validating and co-development phase may include new program logic model and performance measurement framework that contains broader outcome measurements supported by Indigenous partners, if those partners are supportive of using logic models and related program measurement tools as part of co-development discussions. As of: September 2023 |

| We do concur. Sub-Recommendation: 3A) Engage with national and regional economic development organizations that specifically represent intersectional identities to inform the development of capacity building tools, data and gap analysis, and the forthcoming transformative Indigenous procurement strategy. |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: 2022 and is ongoing Completion: Spring 2025 – Return to Cabinet with recommendations for Transformative Indigenous Procurement Strategy |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: As TIPS continues to engage and consult with Indigenous partners to co-develop a transformative Indigenous procurement strategy, a GBA+ lens will continue to be applied to take into account differences affecting access to procurement for Indigenous women, men, and 2SLGBTQI+. As of: October 2023 |

|

| 4) Explore options to increase the funding envelope under IEBD, allowing for greater reach, impact and transparency. This includes recommendations to: 4A) Work with ATC partners to explore long-term funding mechanisms that will better support the sustainability of IFIs and their ability to deliver developmental lending; and 4B) Work with First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners to explore targeted approaches and better leverage existing approaches to support IFIs/MCCs in retaining skilled employees. |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 5) Standardize the PSIB Coordinator role and provide ongoing centralized support to the PSIB Coordinator Network. This support may include ensuring Coordinators have sufficient onboarding, training, and capacity to perform the functions of this role, and that there is a consistent and transparent line of communication between ISC and the Network of Coordinators. | We do concur. The Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business has been developing a GCpedia site, since September 2022 to share information, is updating the Terms of Reference for the Network, and delivering a learning series to better equip PSIB Coordinators in performing their role. |

Director General, Economic and Business Opportunities Branch | Start Date: Since 2019 and is ongoing Completion: April 2025. TIPS will review strategic options for the coordinators network; return to Cabinet 2025, if applicable, could recommend new options. |

Status: Partially Implemented The Transformative Indigenous Procurement Strategy/Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business team hold quarterly Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business Coordinator Network Meetings. In addition, several Planning Workshops have been held that address some of the recommendations. For example, there are workshops on onboarding, reporting, training. In addition, the Transformative Indigenous Procurement Strategy Directorate has begun updating the Coordinators list and will be establishing a more regular meeting schedule in Fall 2023. Indigenous Services Canada will better leverage the network, e.g., broadening its focus to include more Indigenous procurement issues, sharing more tools and best practices, and providing opportunities for suppliers to engage directly with the Network. As of: September 2023 |

Aboriginal Entrepreneurship Program - Access to Capital

Sector: Lands and Economic Development Sector

Program: Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Business Development Program

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Start and Completion Dates | Action Item Context/Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Engage First Nation, Métis and Inuit Partners to explore options to transfer the full IEBD program, including the Indigenous Business Directory and the ABO stream of funding. This includes a recommendation to: 1A) Work with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis partners to fully transfer the Access to Capital program, including the design, delivery, eligibility, and reporting of results on a distinctions basis. |

Recommendation 1: N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| We do concur. Sub-Recommendation: 1A) We will continue to work with Métis Capital Corporations to build their capacity so that they can deliver and we can transfer the remaining ATC sub-components. We will also continue to work together with Inuit partners to explore an Inuit-specific portion of the program. |

Director General, Economic Policy Development Branch | Start Date: October 2022 Completion: October 2025 |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: The ATC stream is moving towards a distinctions-based delivery model. In 2019-2020, the program was partially transferred to Métis Capital Corporations to administer their own Métis-specific portion for two out of the five sub-components: Aboriginal Business Financing Program, and Aboriginal Developmental Lending Allocation. Work is underway with Inuit partners to explore an Inuit-specific portion of the program. This program is now delivered by a network of 54 Indigenous Financial Institutions and five Métis Capital Corporations across the country. As of: October 2023 |

|

| 2) Engage First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners of all program streams to develop an approach to further reduce barriers to entrepreneurship, including by broadening program access for Indigenous Peoples who are harder to reach and/or face exacerbated barriers to the pursuit of entrepreneurship. This includes recommendations to: 2A) Engage First Nation, Inuit, and Métis partners of all program streams to consistently support pre- and post-care for Indigenous entrepreneurs; 2B) Explore and ensuring that the federal procurement process is equally accessible to First Nation, Inuit, and Métis businesses; and 2C) Perform ongoing monitoring of the adjustments resulting from the modernization initiative to ensure that adjustments prove effective. |

We do concur. Recommendation 2: We will continue to work with our partners (National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association, Métis Capital Corporations) to explore approaches to broaden access to capital for Indigenous entrepreneurs, such as by updating the ATC funding sub-components to better-serve Indigenous women and youth as part of the program's modernization. |

Director General, Economic Policy Development Branch | Start Date: April 2021 Completion: October 2025 |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: For several years, ISC has been working together with partners to provide targeted funding for women's programming. Announced in Budget 2021, the $22 million Indigenous Women's Entrepreneurship (IWE) program funded by ISC provides Indigenous women with supports such as financial literacy training and workshops, and a micro-loan program. However, as the IWE program is sunsetting in 2023-24, ISC is actively exploring options for how to modernize the ATC funding to better-serve women and youth initiatives. As of: October 2023 |

| We do concur. Sub-Recommendations: 2A) We will work with our partners on ways to support businesses across all stages of development, such as by exploring ways to include a dedicated pre- and post-care stream as part of the ATC program modernization. 2B) N/A 2C) N/A |

Director General, Economic Policy Development Branch | Start Date: March 2023 Completion: October 2025 |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: ISC is currently working with partners to modernize the AEP-ATC stream to better meet the needs of Indigenous entrepreneurs. This includes enhancements to address the increasing demands for essential equity, and to introduce new sub-components that would fund pre- and post-care supports. As of: October 2023 |

|

| 3) Co-develop with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples a new program logic model and performance measurement framework that contains broader outcome measurements supported by Indigenous partners. This includes a recommendation to: 3A) Collaborate with internal and external partners to expand and employ Gender-Based Analysis Plus to their data collection, and sustainable targeted approaches meeting the needs of diverse groups. |

We do concur. Recommendation 3: We will work with our Indigenous partners (NACCA, MCCs) to co-develop an updated logic model. |

Director General, Economic Policy Development Branch | Start Date: January 2024 Completion: March 2025 |

Status: Implementation did not Commence Update/Rationale: We've been working with our partners, and they've proposed a new logic model based on the ATC modernization goals. As of: October 2023 |

| We do concur. Sub-Recommendation: 3A) We will continue to work with our partners (National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association, Metis Capital Corporations) to expand intersectional data collection and to support an approach for Inuit entrepreneurs. |

Director General, Economic Policy Development Branch | Start Date: October 2020 Completion: 2027 |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: We will work with our partners to expand GBA Plus, as some of our partners are already using GBA Plus (i.e., MCCs, some IFIs through the IWE). As of: October 2023 |

|

| 4) Explore options to increase the funding envelope under IEBD, allowing for greater reach, impact and transparency. This includes recommendations to: 4A) Work with ATC partners to explore long-term funding mechanisms that will better support the sustainability of IFIs and their ability to deliver developmental lending; and 4B) Work with First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners to explore targeted approaches and better leverage existing approaches to support IFIs/MCCs in retaining skilled employees. |

We do concur. Recommendation 4: ISC can work through the fiscal framework on behalf of partners (NACCA, MCCs) to identify funding opportunities. |

Director General, Economic Policy Development Branch | Start Date: October 2021 Completion: October 2025 |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: ISC is currently working with partners to modernize the AEP-ATC stream to better meet the needs of Indigenous entrepreneurs. This includes enhancements to address the increasing demands for essential equity, and to introduce new sub-components that would to broaden program access for Indigenous Peoples who are harder to reach, such as women and youth. As of: October 2023 |

| We do concur. Sub-Recommendation: 4A) We will work with our partners to explore approaches for sufficient and predictable funding. |

Director General, Economic Policy Development Branch | Start Date: October 2022 Completion: October 2025 |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: ISC has been working internally to facilitate a transition to a 10-year contribution agreement with NACCA, which would offer increased flexibility for NACCA to successfully plan and adapt to changes related to the AEP-ATC, and give partners the stability and long-term capacity they need to reduce administrative burden and streamline application processes. As of: October 2023 |

|

| We do concur. Sub-Recommendation: 4B) We will continue to work with our partners (National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association, Metis Capital Corporations) to explore approaches for sufficient and predictable funding to ensure efficient administration of its program and human resources over time. |

Director General, Economic Policy Development Branch | Start Date: October 2022 Completion: October 2025 |

Status: Partially Implemented Update/Rationale: The ATC stream includes a sub-program (Aboriginal Capacity Development Program) that already addresses capacity building, where eligible costs include products and services, consultants, and training costs. As well, ISC is working internally to facilitate a transition to a 10-year contribution agreement with NACCA, which would give partners the stability and help build longer-term capacity. As of: October 2023 |

|

| 5) Standardize the PSIB Coordinator role and provide ongoing centralized support to the PSIB Coordinator Network. This support may include ensuring Coordinators have sufficient onboarding, training, and capacity to perform the functions of this role, and that there is a consistent and transparent line of communication between ISC and the Network of Coordinators. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

1. Introduction

The overall purpose of the evaluation was to examine the Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Business Development Program over the span of 2015-16 to 2020-21. The evaluation examined relevancy, effectiveness, efficiency, and programs' responsiveness to business needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the transfer of the Access to Capital program to Indigenous-led organizations, the evaluation also focused on the service transfer process and resulting impacts. The evaluation findings and resulting recommendations are intended to inform ISC and Indigenous partners on improvements to support future programming decisions.

2. Program description

2.1 Background

The Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Business Development (IEBD) program is a core program under the Lands and Economic Development sector at Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and is designed to support business and economic development efforts of Indigenous entrepreneurs and communities. IEBD is comprised of three program areas that support Indigenous entrepreneurs and business owners in Canada:

Aboriginal Entrepreneurship Program – Access to Capital (ATC) provides funding to establish, expand and diversify the network of Indigenous Financial Institutions (IFIs) and Métis Capital Corporations (MCCs) providing developmental capital to Indigenous entrepreneurs, thereby enhancing access to capital for Indigenous entrepreneurs across Canada. The ATC program is comprised of five complementary sub-programs:

- Aboriginal Business Financing Program which provides equity financing for Indigenous entrepreneurs to obtain commercial loans and to keep the cost of capital affordable, ultimately to increase the number of Indigenous businesses in Canada. IFIs offer non-repayable contributions to eligible Indigenous entrepreneurs up to a maximum of $99,999 and to community-owned Indigenous businesses up to $250,000 which can be used toward eligible expenses related to business start-up and expansion.

- Aboriginal Capacity Development Program which funds ongoing training to support IFIs and MCCs in their continuous efforts to maintain and build capacity and effectiveness as developmental lenders including through product support training, professional development, and business support.

- Aboriginal Developmental Lending Allocation Program which provides a subsidy to IFIs and MCCs that supports them in recovering some of the delivery, administration, and repayment costs associated with the deployment of developmental lending.

- Enhanced Access Program which is a small loan fund that helps IFIs and MCCs serve Indigenous entrepreneurs and communities who normally do not have access to the network of Indigenous-owned and controlled financial institutions for various reasons, including geographical remoteness.

- Interest Rate Buy-Down Program which provides an interest rate subsidy to qualified IFIs and MCCs with a low liquidity ratio to offset the interest costs associated with accessing capital from other financial institutions for additional developmental lending.

Access to Business Opportunities (ABO) provides funding to Indigenous organizations, businesses or individuals to improve access to business opportunities and to enhance the capacity of Indigenous businesses. The program provides national level funding to promote a culture of entrepreneurship for activities including:

- institutional development (e.g., training and development and business supports to business development organization);

- business advisory services and training;

- commercial ventures including business innovation and growth;

- market development; and

- business development and advocacy activities.

Whereas ATC provides funding to the National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association (NACCA) and the MCCs for their operations in support of Indigenous entrepreneurs, ABO funds broad-scale initiatives to support entrepreneurial activity.

Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business (PSIB) seeks to increase federal contracting opportunities and to support Indigenous businesses in gaining access to the federal procurement process, including through enrolment in the Indigenous Business Directory. 90 PSIB coordinators support the strategy across federal departments and agencies, each of which have a target of 5% of all contracts being released to Indigenous businesses.

The IEBD program intends to meet the following outcomes:

Departmental outcome:

- Indigenous communities advance their business development and economic growth.

Ultimate outcome:

- Creation and/or expansion of Indigenous businesses.

Intermediate outcomes:

- A sustainable network of Indigenous-owned and controlled financial institutions in Canada; and

- Indigenous businesses win procurement contracts.

Immediate outcomes:

- IFIs and MCCs have the capacity to deliver business capital and support services;

- Indigenous businesses are competing for federal PSIB set-asides; and

- Public and private procurement, business strategies, and partnerships are implemented.

3. Evaluation methodology

3.1 Scope and evaluation issues

The evaluation covered the thematic areas of relevance, effectiveness, and efficiency over the five-year period from 2015-16 to 2020-21. Given the transfer of the ATC stream to Indigenous-led organizations, additional focus was placed on understanding the service transfer process and impact.

The evaluation used a Gender-Based Analysis Plus lens throughout all evaluation phases and processes. Gender-Based Analysis Plus is an analytical process that provides a rigorous method for the assessment of systemic inequalities, as well as a means to assess how diverse groups of women, men, and gender diverse people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. The "plus" acknowledges that Gender-Based Analysis Plus is not just about differences between biological (sexes) and socio-cultural (genders), it considers many other identity factors such as race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability, and how the interaction between these factors influences the way we might experience government policies and initiatives, which is a commitment of the Government of CanadaFootnote 1. Using Gender-Based Analysis Plus involves taking a gender and diversity-sensitive approach to our work.

This evaluation strove to integrate a GBA+ approach in a variety of ways. Wherever feasible program and survey data were disaggregated across gender, age, location and distinction group. Interview and discussion circles included lines of inquiry that intended to further understand impacts across various identity factors, including impacts for youth, women, individuals in the 2SLGBTQI+ community, and individuals living with disabilities. Where gaps in program data existed, additional secondary data were sought to understand impacts across identity (for instance, in the document review).

The evaluation also used a distinctions-based approach with the intent for the evaluation to reflect the unique interests, priorities and circumstances of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis entrepreneurs. Upon their request, a consultant served as an interface between the evaluation team and the MCCs to support their ability to fully participate.

A Technical Advisory Committee was established to advise on the design of the evaluation and ensure it used culturally relevant and appropriate approaches. The work of the Committee included guiding the evaluation so that it was ethical, methodologically rigorous, and respectful of Indigenous Peoples and communities; ensuring that it addressed the needs of key program partners; helping to identify stakeholders to be engaged in the evaluation; providing feedback on evaluation findings; and supporting the dissemination of results. The Technical Advisory Committee included representatives from the NACCA, IFIs, MCCs, and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. For these meetings, a balance was made in the selection of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Elders, who were invited to support each meeting with an opening and closing prayer and were encouraged to participate in the meeting itself.

The evaluation approach was consultative, inclusive, and collaborative - tailoring methods to provide the most simple and straightforward engagement requirements and valued insight. The approach to the evaluation was refined based on feedback from the Technical Advisory Committee. The evaluation was guided by ethical principles that express the value of human dignity, including:

- Respect for persons;

- Concern for welfare;

- Collaborative;

- Self-determination; and

- Understanding of distinct contextsFootnote 2

These ethical principles were practiced during the key informant interviews and through the dialogue circles in which all persons' ideas and experiences were respected, welfare of all participants was protected, and facilitators ensured a distinction-based approach. For example, the evaluation team conducted interviews confidentially and began with verbal consent from the participant, including whether they agreed to have their interview recorded. The written notes from the interview consultations were shared with the interviewees to review and approve. Any information provided was used by the evaluation team to learn more about how to evolve the programs in the future. Interviewees were informed that all interview notes, transcriptions, and recordings are subject to access to information and privacy requests by the Canadian public as per the Access to Information Act and Privacy ActFootnote 3.

The evaluation was centred on Indigenous worldviews, such as the Seven Grandfather Teachings of the Anishinaabe People (love, respect, honesty, courage, wisdom, humility, and truth) and Two-Eyed Seeing (an approach drawing on the strengths of both Indigenous and Western ways of knowing, for the benefit of all), which were implemented through every phase of the evaluation. The teachings were implemented by following Indigenous protocols such as inviting Elders to open and close the meetings of the Technical Advisory Committee and ensuring representation of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis in this governance structure. The evaluation team implemented Two-Eyed Seeing through the interview questions, ensuring they at once responded to the western-centric evaluation needs while also tapping into Indigenous culture and spirituality. For example, in the interviews, specific questions were asked regarding how programs are aligned with Indigenous cultural and spiritual values and aspirations.

3.2 Design and methods

During the methodological development phase, consultations were undertaken with program representatives and partners to discuss the proposed data collection approach and instruments in detail. This approach permitted the meetings of the full advisory committee to focus more holistically on key topics within the methodology. The evaluation was based on a review of secondary and primary data collected from various engagements (N = 493). A summary of each method employed follows; additional details on the evaluation questions and methods can be found in Annexes B and C, respectively.

Evaluation Lines of Evidence

Literature, Document and File Review

Review of all relevant program documents as they relate to the initial IEBD programs and the transfer of the ATC to NACCA and MCCs, performance data collected by each program, and literature published and accessible online (including academic and grey literature).

Key Informant Interviews

Individual interviews with key informants were conducted to gain insight into the impacts and implementation of IEBD (n = 45). See Appendix A for further details.

Literature, Document and File Review

A survey was conducted with Indigenous entrepreneurs across Canada (n = 441).

Literature, Document and File Review

Discussion Circles were organized with representatives of IFIs, MCCs and PSIB coordinators to allow for more in-depth discussion and sharing of experiences on the programs and their impact.

In this evaluation report, the following terms are used to describe the number of participants who shared their comments or findings highlighted:

Overwhelming Majority: over 75% of the respondent group

Majority: more than 50% up to 75% of the respondent group

Some: between 25 to 50% of the respondent group

Few: under 25% of the respondent group

3.3 Limitations

The evaluation encountered a few limitations to data collection. There was limited access to performance data related to the impact of the program beyond the individual borrower. However, the team attempted to understand the broader impacts of the program, including the impact that entrepreneurship is having at the community- and family-level (e.g., the multiplier effect), through interviews, Discussion Circles and a survey. Also, few scholarly articles discuss Indigenous entrepreneurship and business approaches in Canada and around the world, and the periodic surveys that do take place have small sample sizes.Footnote 4

The evaluation team encountered challenges in reaching representative respondents to inform the evaluation, particularly through the survey. When the survey was first launched in September 2022, the responses received were primarily from Métis entrepreneurs and there was not proportional representation of First Nation and Inuit entrepreneurs to provide a full lens on Indigenous perspectives related to starting and sustaining Indigenous businesses. As a result, the survey was relaunched in November 2022 to enhance outreach to First Nation and Inuit entrepreneurs who have accessed the ATC program and, ultimately, to increase the response rate. This relaunch succeeded in expanding the reach and led to a higher number and broader base of participants, but Inuit entrepreneurs continued to be under-represented in the response. The outreach supports provided by NACCA, IFIs and MCCs encouraged a strong response; however, the response rate may have been affected by the approach to survey recruitment and collection as only online methods were used. This may have particularly posed an issue for entrepreneurs living in Northern, rural, or remote areas with limited broadband connection. Additionally, it is possible that not all IFIs/MCCs shared the invite to participate with their client base.

The evaluation team encountered challenges in gathering data and information to assess how the accessible the programs are to individuals across identity characteristics, and particularly those who are most marginalized. NACCA has introduced programs that are targeted to women and youth; however, it is more challenging to understand, for example, how two-spirited, Elders, those with disabilities and/or those from rural communities are accessing IEBD programs. This was largely attributed to the fact that most of the IFIs and MCCs provide character-based lending based on both their knowledge of the borrower, and the viability of the proposed business. In these cases, decisions are made based on business viability as opposed to how the applicant identifies. Additionally, the PSIB and ABO streams of the program collected limited data to support the assessment of access or impacts across any sub-groups of the population.

4.0 Key findings

4.1 Key findings: Relevance

Summary of findings

The IEBD program remains relevant to both the priorities of the federal government of Indigenous Peoples, particularly following the transfer of the program from ISC to Indigenous-led organizations.

Finding 1: The programs align with economic reconciliation and self-determination, which supports the wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples, and in turn, supports families and communities. The transfer of the delivery of the ATC program to Indigenous-led organizations is aligned with both Indigenous and federal priorities and is viewed positively by the Indigenous Peoples who were consulted.

"Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples remains a core priority for this Government, and it will continue to move forward as a partner on the journey of reconciliation".

Source: Speech from the Throne, 2019

The evaluation found strong evidence that the IEBD program continues to align with federal priorities and mandates. The Government of Canada's commitment to economic reconciliation has been emphasized in budget announcements over the scoping years, including the investment of $25 million in Budget 2016 to support economic development of the Métis Nation and the announcement in 2019 of $50 million to enhance the funding of MCCs to support small and medium-sized enterprises through the ATC programFootnote 5. Additional investments announced in Budget 2021 to grow the Aboriginal Entrepreneurship Program illustrate alignment with this commitment by directly supporting wealth generation through access to capital and business opportunitiesFootnote 6. The program is also aligned with upholding the rights of Indigenous Peoples as stated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, Article 21: "Indigenous Peoples have the right, without discrimination, to the improvement of their economic and social conditions…"Footnote 7. The responsibility of ISC specifically in advancing economic reconciliation is stated in the recent United Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act Action Plan for 2023-2028, including by addressing impacts of colonization and inequitable policiesFootnote 8. For example, the Act recognizes the need to repeal the Indian Act in order for Canada's laws to fulfil the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; such a repeal is expected to inherently reduce barriers to entrepreneurship faced by Indigenous entrepreneurs (i.e., access to capital) and advance economic reconciliationFootnote 9.

The federal commitment to economic reconciliation is aligned with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action 92 on Business and ReconciliationFootnote 10, and Call for Justice 4.2 of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls related to self-determination in economic social developmentFootnote 11. The IEBD program supports these Calls by advancing self-determination through the transfer of the ATC program to NACCA and MCCs; providing funding and programs that support the development of an Indigenous-led financial sector; and helping to remove barriers to business start-up including access to capital and long-term sustainability. The transfer of ATC to NACCA and MCCs directly supports the mandate of Indigenous Services Canada to empower Indigenous Peoples to independently deliver services. The transfer of services is also in direct alignment with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, Article 3: "Indigenous Peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development"Footnote 12.

"…there is no way government can ensure this alignment [with Indigenous priorities]; that's up to us to follow the cultural practices within our areas. We don't invest in efforts that don't align with cultural and spiritual values, and we are the only ones who can assess that."

Source: IFI Discussion Circle

The transfer of delivery of the ATC program to NACCA and the MCCs has improved the cultural relevance of the program and supported Indigenous entrepreneurs, families, and communities. Most Indigenous entrepreneurs who participated in the evaluation survey (87%) indicated a higher level of trust in IFIs/MCCs than mainstream banking systems. When asked how the IFIs and/or MCCs are aligned with their cultural and spiritual values and aspirations, survey respondents described that they share a common vision and goal and that IFIs/MCCs care for the wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples and support self-determined success. Representatives of IFIs and MCCs shared similar points, including that business supports are most relevant when they are delivered by Indigenous organizations.

4.2 Key findings: Service Transfer

Summary of findings

The transfer of the ATC stream from ISC to NACCA and to the MCCs went well and is widely supported by Indigenous partners. Indigenous entrepreneurs feel a stronger and more personal relationship with IFIs/MCCs than mainstream lending institutions. However, since the transfer of the ATC program was limited to provision of contributions, further work is required to fully transfer the suite of IEBD programs. Also, the siloed approach to funding across IEBD streams creates additional challenges for entrepreneurs, particularly surrounding navigating various supports and requirements.

Finding 2: The transfer of the ATC stream from ISC to NACCA and to the MCCs went well and the relationships between the Indigenous partner organizations, and between Indigenous entrepreneurs and IFIs/MCCs, are positive.

In 2015, responsibility for the ATC program was transferred from Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada to NACCA. A NACCA representative indicated that the transfer was originally identified as part of the Department's Deficit Reduction Action Plan, aimed at reducing expenditures of the federal government. Interviewees indicated that the planning process went well, and was guided by a joint planning committee and working group to oversee the transfer. The joint planning committee outlined direction on how the program would be set up once transferred to NACCA. Some representatives of IFIs noted that distribution of funds is quicker under NACCA than the previous model, and that IFIs are able to more efficiently and effectively deliver the service under the transferred model. Many representatives of IFIs described a strong and trusting relationship with NACCA, featuring greater transparency of the program than with ISC. To support a distinctions-based approach to service delivery, in 2019 select MCCs were transferred a portion of the ATC program to administer two program sub-components: the Aboriginal Business Financing Program and Aboriginal Developmental Lending Assistance. The majority of MCCs interviewed and one ATC staff member indicated that transfer to MCCs has fostered a stronger Métis business climate resulting from a greater ability to support the unique and under-served needs of Métis entrepreneurs. At the time of evaluation, Inuit organizations had yet to be transferred control of any aspects of the ATC program. Although Inuit entrepreneurs are eligible to receive funding delivered through IFIs, it is anticipated that ISC will continue to advance program transfer and self-determination by engaging Inuit to ensure that any challenges associated with access and eligibility are addressed as per the Inuit Nunangat PolicyFootnote 13.

"In the future, the programs need to be Indigenous led - NACCA and others, - they are the ones who should be developing and designing the next suite of programs according to what they know and what they need with greater flexibility– it has to be developed by them."

Source: ATC Staff

The majority of representatives from NACCA, IFIs and MCCs underscored the importance of having the delivery of some of the IEBD programs in the hands of Indigenous-led organizations. Representatives of NACCA, IFIs, and MCCs noted that the transfer of services has allowed for improved and more flexible service delivery, fewer administrative costs, and a stronger Indigenous business climate. Similarly, 86% percent of survey participants indicated a preference to work with the IFIs and MCCs in the future as opposed to mainstream banking; agreement with this statement was highest for youth (94%). In total, 94% of respondents indicated they would access support from an IFI again, with 91% of women agreeing with this statement compared to 98% of men; a slightly higher percentage of Métis (96%) participants agreed with this statement compared to First Nation participants (93%). Survey respondents agreed they are being adequately served by IFIs/MCCs (81%), though the proportion of participants in agreement was somewhat lower for men than women (79%, 84% respectively). When asked what makes the lending relationship with IFIs/MCCs different from that of a mainstream bank, survey respondents most frequently described a more personal relationship, and that they are working with Indigenous Peoples who understand their reality.

"It is about agreements and funding. 10-year agreements have more flexibility and how funding is used and ability to move money and in relation to reporting."

Source: NACCA representative

A few ATC staff and a NACCA representative indicated a need for more guidelines and ability to hold IFIs and MCCs accountable for complying with program requirements. In addition, a few ATC staff and IFIs noted that whereas one IFI might deny a loan to an applicant, another IFI will approve a loan to the same applicant. This lack of consistency across the program was identified as a challenge that needs to be addressed, as there is no existing framework in place to ensure consistent implementation of the program. Key areas where problems were reported include levels of reporting and the consistent application of eligibility requirements.

Finding 3: The transfer of the ATC program is limited to contributions and does not include foundational aspects such as program design, expected outcomes, and performance monitoring. Further work is required to fully transfer control of the ATC program and the remaining IEBD streams to Indigenous-led organizations.

"Government still controls the rules of engagement. NACCA has a strong voice in how the funds are delivered through the IFIs – this is good but not the same as transferring the whole program to a First Nation Authority. A lot more can be done."

Source: IFI Interview

Although the transfer of the ATC program has had significant positive impacts on advancing self-determination and cultural relevance of the program, representatives of NACCA, MCCs and IFIs indicated that the transfer was limited to the delivery of contributions, as opposed to control over the program design, administration, expected outcomes, and reporting frameworks. For example, NACCA contracted Goss Gilroy Inc. in 2020 to conduct a comprehensive review of the program internally from the perspective of IFIs, which included the development of a new logic model, indicators, and outcomes. However, the reporting requirements from the government did not adapt to reflect this work. Further, the lack of control or co-development of measurement frameworks has led to burdensome requirements and timelines for MCCs, IFIs, and NACCA. Representatives of these organizations view the reporting requirements as burdensome and question the relevance of some of the indicators. NACCA and MCCs have not been transferred control over key aspects in the Terms and Conditions of the program, such as recipient and initiative eligibility, which could benefit from flexibility and/or the discretion of the Indigenous partners. One representative of an MCC reflected that although the transfer has benefited the nation-to-nation relationship, at present, the ATC program is the "same program, operating the same way"; the primary change is that the funding agreement is directly with ISC. Some representatives of MCCs also reflected on receiving less funding following the distinctions-based transfer. One MCC expressed that the reduction in funding ultimately limited their sustainability as a lender, as "there was no way we could take the Aboriginal Developmental Lending Assistance 13% at the expense of the recipients". Instead, they allocated the Aboriginal Developmental Lending Assistance component of funding into Aboriginal Business Financing Program to meet needs of recipients, despite the impact on their organization by taking on the fulsome cost of developmental lending.

NACCA and the MCCs have short-term funding agreements with ISC, which creates challenges in administering funds and achieving impacts as IFIs and MCCs lack certainty as to if or when funds will be available to them in the next fiscal year. Representatives of NACCA shared frustrations with the timeliness of funding roll-out related to these short-term funding agreements, and would benefit from predictable, long-term funding. ATC staff, NACCA representatives and a few IFI and MCC representatives noted that the flexibility of funding is essential to allow NACCA and IFIs/MCCs to move money between sub-program allocations and across fiscal years. Representatives of NACCA and the IFIs identified the need to develop 10-year block funding agreements with a sliding scale that can allow flexibilities in response to changes due to inflation or needs. These changes would align with the Department's statute and mandate to transfer federal programs and services to Indigenous-led organizations. A fulsome transfer would also align with Article 23 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act which specifically affirms the right of Indigenous Peoples to be actively involved in the development of priorities and strategies for exercising their right to development (e.g., health, housing, and other economic and social programmes) and to administer these programmes through their own institutionsFootnote 14. At the time of evaluation, ISC has not developed a distinctions-based transfer to Inuit organization(s), which is recommended, and will require collaboration from the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency who delivers similar programming in the North.

The majority of those consulted from NACCA, IFIs, and MCCs and some ISC staff shared a strong desire for a fulsome transfer of all program elements, including the Indigenous Business Directory and PSIB. For the Indigenous partners, the full transfer would represent real steps towards reconciliation as opposed to being a funding delivery arm of government. In looking to the future, one PSIB interviewee noted that they are exploring a procurement hub platform that would be Indigenous-led, which is intended to be far easier for Indigenous businesses to navigate the system. Indigenous partners recognize a challenge in PSIB in the absence of Indigenous partners in policy development and oversight.

4.3 Key Findings: Effectiveness

Summary of findings

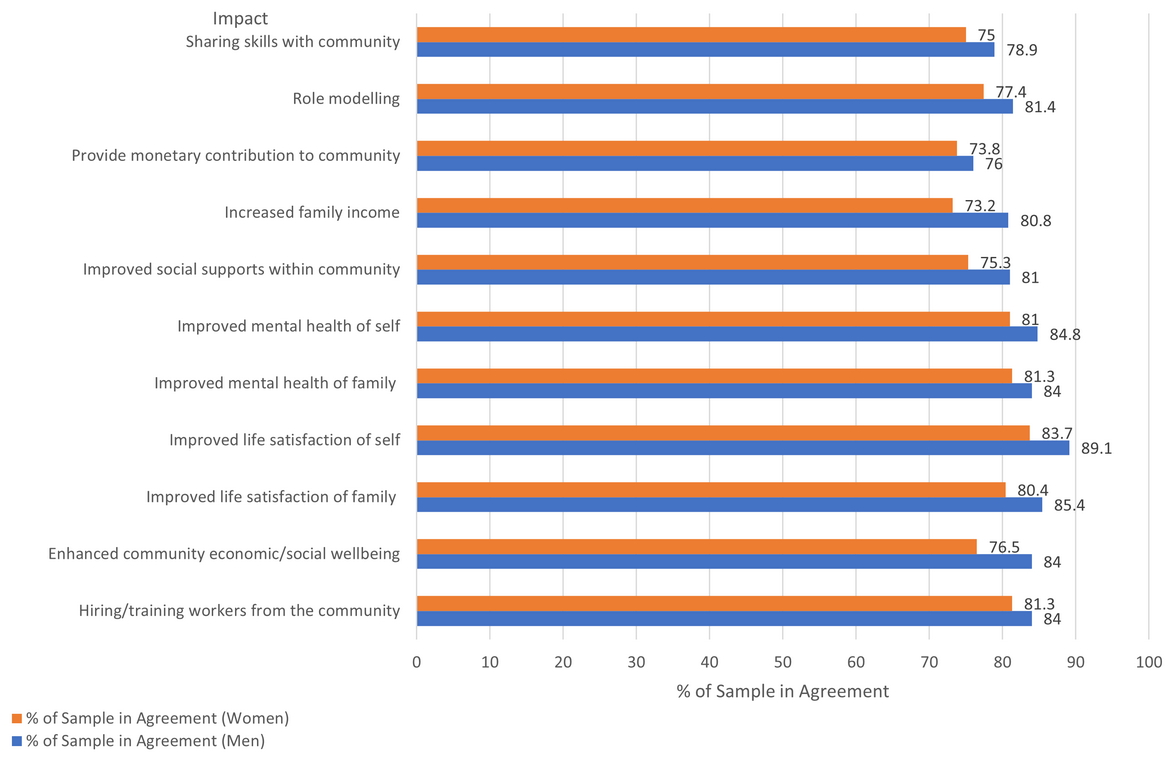

The IEBD program helps remove barriers to Indigenous Peoples seeking business capital and supports and is meeting the intended outcomes of sustaining the network of Indigenous lending institutions, creating and expanding Indigenous businesses, and creating or maintaining jobs through lending. In addition, the program has impacts at the individual-, family-, and community-levels.

However, additional barriers hinder Indigenous entrepreneurship and business growth beyond current program scope. There is an ongoing need for targeted investments in pre- and post-care. The anticipated growth in the Indigenous population is expected to increase the demand for entrepreneurial supports for Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Although efforts have been made to improve the inclusivity and reach of programs across distinctions, gender and age groups, more work is needed to reach and monitor equity in access. Limited data were available under PSIB and ABO to effectively assess broader diversity impacts. The current logic model and inconsistent program data do not reflect outcomes relevant to Indigenous entrepreneurs nor do they allow for the assessment of impacts of the programs. An updated performance measurement framework is required that reflects outcomes relevant to Indigenous entrepreneurs and key program partners.

Finding 4: ATC has helped to create a network of sustainable Indigenous-led lending institutions; however, IFIs and MCCs continue to face challenges with retaining skilled employees in a competitive market.

"The network of AFIs is a leading global practice, it is second to none."

Source: IFI Discussion Circle

There is agreement among the majority of interviewees that the program has helped to enhance the capacity of the IFIs and MCCs and has helped to create and expand the network of Indigenous-led lending institutions in Canada. This has resulted in Indigenous entrepreneurs and businesses having more choice of lenders who are more sensitive to their needs and with a better understanding of their culture. The programs are creating a sustainable and resilient network of Indigenous lenders, with the goal of shifting from the "lender of last resort" to the "lender of choice".

"We need to invest in more staff training to deliver services. We are competing with traditional financial institutions for staffing. Often we are not bringing in folks with business lending experience and we are too small to invest in staff training."

Source: MCC Interview

NACCA recognizes that the IFIs have a range of different capacities, focuses and priorities; NACCA and IFI representatives identified the importance of finding ways to support the differing capacity requirements of the IFIs and MCCs. While some IFIs wish to continue focusing on developmental lending, others seek to grow their range of services into new sectors and products, larger loans and ventures, and social financing. Most IFIs in the discussion circles also noted that ATC is only one part of their lending portfolio. Some IFIs and MCCs noted that the commitment by government to zero-interest loans can undermine the IFIs' ability to cover their operational expenses. The IFI discussion circles also identified challenges with accessing Aboriginal Developmental Lending Assistance. Participants in two IFI discussion circles agreed that access to Aboriginal Developmental Lending Assistance was on the decline – particularly after the separation of the MCCs outside of NACCA, and for some IFIs, Aboriginal Developmental Lending Assistance is a critical support to their long-term sustainability. Annual reports published by NACCA suggest that Aboriginal Developmental Lending Assistance has been consistently accessed by 19 IFIs annually since 2018-19 aside from a dip to 17 in 2020-21, and the dollar value of Aboriginal Developmental Lending Assistance funds paid to IFIs increasedFootnote 15.

"Often First Nations, Métis and Inuit are precluded so they have been neglected by financial institutions. The program helps to removes significant systemic barrier because of the context of First Nations and Métis peoples and the Indian Act."

Source: IFI Discussion Circle