Evaluation of Land Management Sub-Programs

PDF Version (736 Kb, 76 pages)

Table of contents

- List of abbreviations and acronyms

- Executive summary

- Background

- Evaluation scope and methodology

- Key Findings

- Recommendations

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Overall management response

- Action Plan matrix

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Program Description

- 3. Evaluation Methodology

- 4. Findings: Importance of Land

- 5. Findings: Current Challenges

- 6. Findings: Ways to move forward

- 7. Conclusions and recommendations

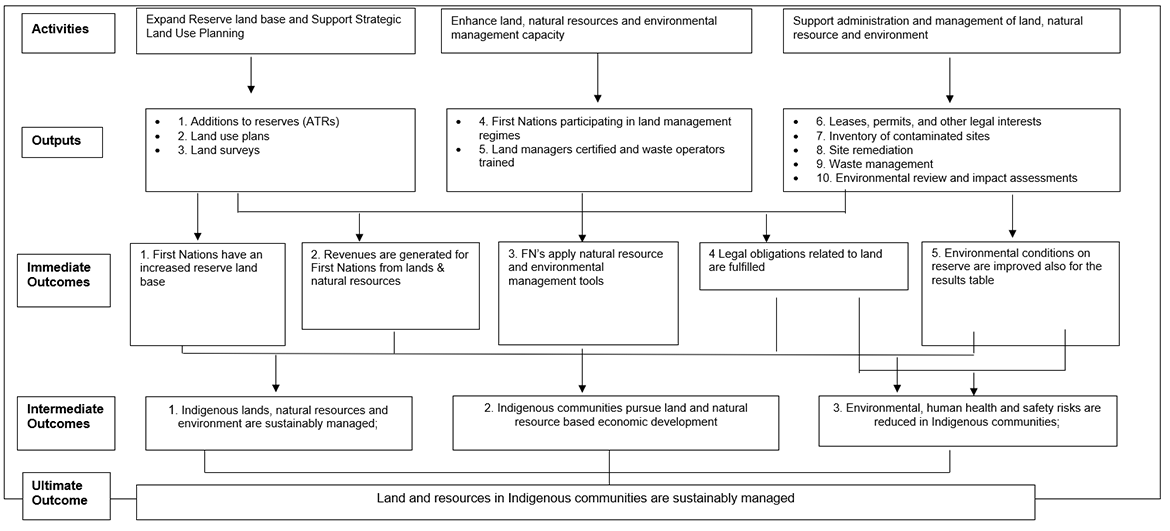

- Appendix A: Logic Model for Land, Natural Resource, and Environmental Management

- Appendix B: Terms of Reference

- Appendix C: Comprehensive methodology

List of abbreviations and acronyms

- CIRNAC

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

- GIS

- Geographic Information System

- ISC

- Indigenous Services Canada

- ILRS

- Indian Land Registry System

- LEDSP

- Lands and Economic Development Support Program

- LNREM

- Land, Natural Resources and Environmental Management

- NALMA

- National Aboriginal Land Managers Association

- NIEDB

- National Indigenous Economic Development Board

- PLMCP

- Professional Land Manager Certification Program

- RC

- (First Nations Land Management) Resource Centre

- RLA

- Regional Land Association

Executive summary

The evaluation of Land Management Sub-Programs was outlined in the 2021-22 Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) Five Year Evaluation Plan, and conducted in compliance with the Treasury Board of Canada Policy on Results. The evaluation was undertaken to provide a neutral and evidence based assessment of: relevance; performance; best practices; and service transfer in First Nations lands management.

Background

The evaluation focuses on three lines of service within ISC's Land, Natural Resource and Environment Management Portfolio within the Lands and Economic Development Sector:

- Reserve Land and Environment Management Program. The key activity is to provide funding to First Nations to develop the capacity needed to exercise increased responsibility over the management of reserve land, resources and environment under the Indian Act.

- ISC supports for First Nations Land Management. The key activity is to provide funding to First Nations organizations and communities to empower First Nations to exercise their jurisdiction under the Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management. With this Agreement, First Nations opt out of lands-related sections of the Indian Act and manage their reserve lands, resources and environment according to their own laws, values and priorities while also enabling improved economic development.

- Land Use Planning. The key activity is to provide funding to First Nations lands organizations, who in turn support First Nations in developing community-led Land Use Plans which become primary tools for governing over reserve lands.

The ultimate goal of ISC's interventions in this portfolio is that Indigenous communities benefit from the sustainable development and management of their lands and natural resources.

Evaluation scope and methodology

This evaluation covered the years 2014-15 to 2020-21 as per Treasury Board requirementsFootnote 1, and selected activities up to the 2021-22 fiscal year to recognize and provide feedback on impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although not part of the original scope, the evaluation also incorporated more recent data and actions taken by ISC to implement the mandate of the department since its creation in 2017-18.

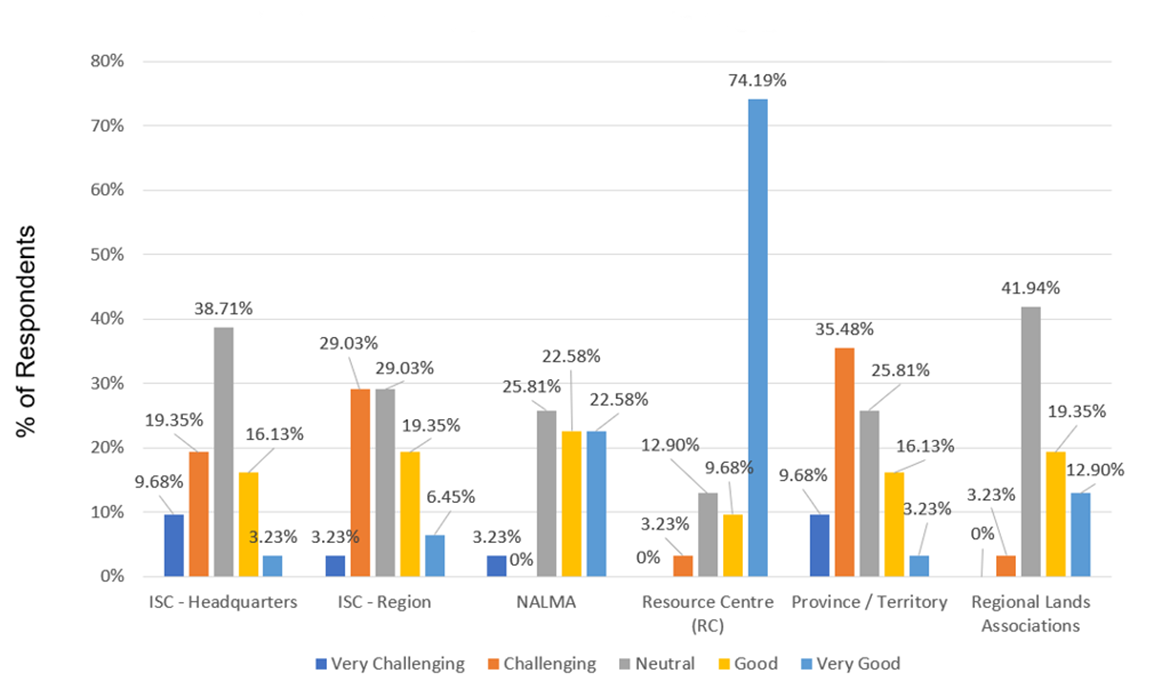

The Methodology Report was approved in May 2022, with primary data collection occurring from May 2022 to October 2022. The evaluation relied on a mixed-methods approach that included the following lines of evidence: a document, literature and media review; 44 interviews with ISC representatives and external funding recipients and service delivery partners at the national and regional level; 40 complete and 40 partially-complete surveys from individuals involved in land management at the First Nation community level; content and feedback from participants of 5 conferences hosted by First Nation Regional Lands Associations (RLAs); 6 community site visits in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Nova Scotia; and an analysis of quantitative administrative data held by the Community Lands Directorate at ISC Headquarters.

Key Findings

The evaluation found repetition of key concepts in the findings across the standard evaluation areas of relevance and performance, and presents its findings thematically according to the information shared by ISC interviewees and First Nations organization and community representatives. Eight themes were identified, and fall into three broad categories.

| Importance of Land | Current Challenges | Ways to Move Forward |

|---|---|---|

| Community and Culture Self-Determination |

Funding Capacity Cross-Cutting Issues |

Relationships Reporting Service Transfer |

Importance of land

With respect to community and culture, First Nations interviewees and survey respondents shared that planning for the future use of land is an important intergenerational aspect of First Nations' community-building. The evaluation also reaffirmed that self-determination is an inherent right for First Nations, and there are ways that ISC can support communities to exercise that right over their lands and natural resources. The implementation of the United Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was identified as an area where Canada can work with First Nations to decolonize its lands-related structures and processes.

Current challenges

The evaluation found that there are disparities in funding access and distribution across and within land management initiatives which create differences in opportunities for First Nations to benefit from their lands and natural resources. While funding for First Nations Land Management is seen as mostly streamlined, the evaluation found that Land Use Planning would benefit from stable multi-year funding arrangements. The evaluation found that the effectiveness of the Reserve Land and Environment Management Program is hindered by inadequate funding and is not currently meeting its objectives related to capacity development. Further, First Nations interviewees and survey respondents indicated that the funding formula for this Program does not reflect the land management realities for many First Nations, as it is too transaction-focused. It was noted that a best practice in this area is to implement block or grant funding arrangements to provide First Nations organizations and communities with flexibility to address emerging lands priorities.

In terms of capacity for First Nations communities to effectively manage lands, the evaluation found that an appropriately compensated and dedicated land manager is vital. Interviewees and survey respondents from First Nations communities and organizations shared that their partners in the Lands sector, such as different levels of government and private organizations, could benefit from training around reserve land management, and that enforcement of First Nations' laws under their land codes is a critical challenge that is not easily addressed by ISC alone. The evaluation also covered cross-cutting issues around climate change and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and found that First Nations are not currently receiving adequate support to mitigate the serious impacts of climate change on their lands and natural resources, and that COVID-19 created challenges for communities to achieve their land management priorities.

Ways to move forward

The evaluation found that First Nations are developing complex land management ecosystems by building relationships outside of ISC, and that ISC has opportunities to improve its relationships with First Nations communities. In particular, the evaluation heard from both ISC and First Nations interviewees and survey respondents that staff turnover within the ISC regional offices hinders effective relationship-building between First Nations' Lands offices and the department. Reporting practices can support better relationships with First Nations and there are opportunities for ISC to streamline and improve the utility of reports it requires from First Nations partner organizations and communities for land management funding. The evaluation included a lens on service transfer and found that the transfer of lands management speaks to a future where First Nations have the control they desire in managing their lands and natural resources. As the department moves toward service transfer, ISC has a further role to play in land management while First Nations organizations and communities continue to develop their lands-related authorities.

Recommendations

- As First Nations in the Reserve Land and Environmental Management Program (RLEMP) experience disparities within the current model that hinders their capacity to effectively manage their lands and natural resources, ISC re-assess the funding formula for RLEMP.

- Working with First Nations partners, ISC undertake a gaps analysis for training in lands governance, at the discretion of First Nations partners.

- Working with Regions, Human Resources, and the Chief Finances Results Delivery Office (CFRDO), ISC lead an organizational capacity assessment across land management, focusing on training needs, human resource continuity and retention of corporate knowledge for ISC staff.

- Working with First Nations partners, ISC provide funding and support to carry out studies on existing capacity for land management in First Nations communities.

- Working with First Nations partners and the Chief Data Officer, ISC explore how to ensure First Nations have access to and ownership of their lands-related data, and the necessary data governance and management capacity to support that access and ownership, in support of service transfer and in order to facilitate evidence-based decision-making in land management.

Management Response and Action Plan

Evaluation Title: Evaluation of Land Management Sub-Programs

Overall management response

Overview

- This Management Response and Action Plan was developed to address recommendations presented in the Evaluation of Land Management Sub-Programs. It was developed by the Lands and Economic Development Sector (LED) in collaboration with the Evaluation Directorate.

- The Lands and Environmental Management Branch (LEMB) within LED at ISC acknowledges and concurs with the recommendations set forth in the Evaluation of Land Management Sub-Programs report produced by ISC's Evaluation Directorate.

- Wherever possible, LEMB intends to implement recommendations immediately and in the spirit of ISC's departmental mandate to support Indigenous peoples in assuming the control of the delivery of services at the pace and in the ways they choose. As one of its roles, LEMB, through the Community Lands Development Directorate, supports First Nations in building land management capacity and increasing land governance control both under the Indian Act, through the Reserve Land and Environment Management Program (RLEMP), and external to the Indian Act, through the Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management. Many of the recommendations in this evaluation reflect challenges both LEMB and First Nation partners, namely the National Aboriginal Lands Managers Association (NALMA) and the First Nations Land Management Resource Centre (FNLMRC), are aware of and have begun to address since the conclusion of the evaluation period in 2021. Moreover, recommendations in this evaluation are already linked to the implementation of Budget 2023 funding announcements for RLEMP and First Nations Land Management (FNLM). LEMB's Management Response and Action Plan for the Evaluation of Land Management Sub-Programs, with associated timelines, has been developed with this context in mind, to ensure existing efforts are brought to fruition prior to determining next steps.

- Because of the nature of self-governance and extent of service transfer in land management supports to First Nations, specifically for FNLM and Land Use Planning (LUP), it is important to note that ISC often plays a supporting role to efforts led by First Nation partners. Nevertheless, LEMB continues to enjoy effective relationships with land management service delivery partners and will work in partnership with them to implement recommendations made in this evaluation as well as to continue to make improvements to land management sub-programs.

Assurance

- The Action Plan presents appropriate and realistic measures to address the evaluation's recommendations, as well as timelines for initiating and completing the actions.

- Periodic reviews of the Management Response and Action Plan will be conducted by ISC Evaluation and shared with the ISC Performance Management and Evaluation Committee to monitor progress and activities.

Action Plan matrix

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title/Sector) | Planned Start and Completion Dates | Action Item Context/Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. As First Nations in RLEMP experience disparities within the current model that hinders their capacity to effectively manage their lands and natural resources, ISC re-assess the funding formula for RLEMP. | We do concur. Action 1.1: Implement a base-level of funding for existing and new First Nations participants in RLEMP (Q3 2023-2024). Action 1.2: With NALMA, ISC sectors and ISC regional offices, provide progress reports on status of discussions to explore potential options to further improve the RLEMP funding formula to support increased capacity and lessen disparities (Q4 2025-26). Action 1.3: Report on findings, including recommendations for improvement to the RLEMP funding formula beyond the implementation of a base-level of funding (Q3 2026-2027). |

Director General, Lands and Environmental Management Branch, Lands and Economic Development Sector, Indigenous Services Canada | Start Date: August 2023 Completion: December 2026

|

Status

As of: |

| 2. Working with First Nations partners, ISC support a gaps analysis for training in lands governance, at the discretion of First Nations partners. | We do concur. In the case of FNLM, due to the extent of service transfer and given it is a self-government initiative, ISC does not control decisions pertaining to mandatory training. To support this recommendation for FNLM, LEMB will: Action 2.1: Provide progress reports on status of work with the FNLMRC to support the implementation of Budget 2023 funding. This funding includes new positions for training curriculum development at the FNLMRC to strengthen their ability to work with First Nations to address training needs. beginning in fiscal year 2023-2024 (Q1 2024-2025). In the case of RLEMP, during the COVID-19 pandemic, NALMA undertook an appraisal of their Professional Land Management Certification Program (PLMCP). Based on its recommendations, they redesigned their training program and materials to be more practical, specialised and tailored to the needs of the participants. There is now a clear roadmap for training required for Land Manager certification, as well as elective/ specialized training available to respond to individual First Nations' needs or aspirations. To support this recommendation for RLEMP, LEMB will: Action 2.2: Provide progress reports on supports provided to NALMA in the development, delivery and promotion of available training (Q3 2023-2024 to Q1 2024-2025). Action 2.3: Support NALMA in undertaking an independent review/evaluation of the redesigned PLMCP (Q1 to Q4 2025-2026). |

Director General, Lands and Environmental Management Branch, Lands and Economic Development Sector, Indigenous Services Canada | Start Date: October 2023 Completion: March 2026

|

Status

As of: |

| 3. Working with Regions, Human Resources, and the Chief Finances Results Delivery Office (CFRDO), ISC lead an organizational capacity assessment across land management, focusing on training needs, human resource continuity and retention of corporate knowledge for ISC staff. | We do concur. Action 3.1: Provide progress reports on status of engagements with internal partners (regions, human resources, CFRDO) to determine a suitable approach to analyze land management organizational capacity needs (Q3 2023-2024). Action 3.2: Undertake the assessment of ISC land management organizational capacity needs determined in Action 3.1 (Q3 2024-2025). Action 3.3: Disseminate and report on the results of the capacity assessment, and identify next steps on any recommendations (Q4 2024-2025) |

Director General, Lands and Environmental Management Branch, Lands and Economic Development Sector, Indigenous Services Canada | Start Date: October 2023 Completion: December 2024

|

Status

As of: |

| 4. Working with First Nations partners, ISC provide funding and support to carry out studies on existing capacity for land management in First Nations communities. | We do concur. To support this recommendation for FNLM, LEMB will: Action 4.1: Engage with the FNLMRC to gauge interest and to identify priorities and options for land management capacity studies (Q4 2023-2024). Action 4.2: Provide progress reports on status of support provided to the FNLMRC to undertake and lead land management capacity studies as requested (Q1 to Q4 2024-2025). Action 4.3: Report internally on the results of studies undertaken should FNLMRC choose to undertake them (Q3 2025-2026). In the case of RLEMP, during the COVID-19 pandemic, NALMA carried out studies on existing capacity and implemented new and improved training in response. To support this recommendation for RLEMP, LEMB will: Action 4.4: Provide progress reports on status of engagements with NALMA and Regional Lands Associations to identify and fund other capacity assessments, as resources allow (Q1 to Q3 2025-2026). Action 4.5: Support NALMA in the evaluation of the redesigned PLMCP, which may include undertaking an assessment on the trained workforce (Q1 to Q4 2025-2026). |

Director General, Lands and Environmental Management Branch, Lands and Economic Development Sector, Indigenous Services Canada | Start Date: October 2023 Completion: March 2026

|

Status

As of: |

| 5. Working with First Nations partners and the Chief Data Officer, ISC explore how to ensure First Nations have access to and ownership of their lands-related data in order to facilitate evidence-based decision-making in land management. | We do concur. It is important to note that significant efforts have been made within LEMB since the evaluation period to support this recommendation by undertaking work on:

|

Director General, Lands and Environmental Management Branch, Lands and Economic Development Sector, Indigenous Services Canada | Start Date: October 2023 Completion: December 2026

|

Status

As of: |

1. Introduction

The overall purpose of the evaluation was to examine Land Management Sub-ProgramsFootnote 2, as outlined in the Five-Year Evaluation Plan of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), and in compliance with the Treasury Board (TB) of Canada Policy on Results. The evaluation focused on three aspects of the Land, Natural Resources and Environmental Management portfolio at ISC: the Reserve Land and Environment Management Program (RLEMP), ISC supports for First Nations Land Management (FNLM), and Land Use Planning.

2. Program Description

2.1 Background

ISC funds a suite of service lines that make up the Lands, Natural Resources and Environmental Management portfolio. The department works with First Nation communities to achieve a variety of objectives related to land and the environment. ISC and First Nations develop innovative policy, process, and system improvements to enhance conditions to increase the reserve land base, and support sustainable management of land, environment and natural resources that leverages community and economic development opportunities. ISC also works to facilitate greater First Nation independence or self-sufficiency in managing land, environment and natural resources via support and funding for sectoral self-governance agreements.Footnote 3

These governance investments provide core and targeted funding to First Nation governments, as well as Aboriginal institutions and organizations to:

- Provide support for communities through planning, capacity building, and training to effectively manage land, natural resources, and environmental activities;

- Modernize land administration tools, systems, procedures, and practices for First Nations operating under the Indian Act; and

- Address legal obligations, community growth, and economic development through the additions of lands to reserve.

This evaluation did not cover all of the service lines listed under the Lands, Natural Resources and Environmental Management portfolio; those not included are either exempt from evaluation, have been covered in previous evaluations, or will be included in upcoming evaluations. See Appendix A for more information on the service lines within the portfolio and what has been excluded.

2.2 Overview of Land Management

2.2.1 Overall objectives and expected outcomes

The Lands, Natural Resources and Environmental Management portfolio has a variety of objectives, and this evaluation focused on the sustainable management of First Nations' land. According to the program's logic model (found in Appendix A), the ultimate outcome of ISC's interventions is that land and resources in Indigenous communities are sustainably managed.

The three medium-term or intermediate outcomes have been identified as:

- Indigenous lands, natural resources and environment are sustainably managed;

- Indigenous communities pursue land and natural resource based economic development; and

- Environmental, human health and safety risks are reduced in Indigenous communities.

ISC provides support and funding to First Nations to participate in RLEMP and Land Use Planning, which is intended to contribute to progress towards these outcomes. ISC supports First Nations communities to participate in First Nations Land Management (FNLM), though throughout the temporal scope of this evaluation this contributed to a different logic model focused on First Nations Jurisdiction Over Land and Economic Development. ISC's support for FNLM has since been moved under the Lands, Natural Resources and Environmental Management portfolio, though the present logic model does not yet address this area. ISC also provides funding to two First Nations organizations (see below), who are the major service delivery partners in land management.

2.2.2 Service delivery partners

The main service delivery partner for First Nations managing their reserve lands under the Indian Act is the National Aboriginal Land Managers Association (NALMA). NALMA offers technical support, channels for networking, and professional development opportunities for First Nations land managers. NALMA works with eight regional branches known as Regional Lands Associations (RLAs) which provide regionally-specific supports and services to First Nations in each province, and to Inuit communities in Nunavut.

The First Nations Land Management Resource Centre (FNLMRC, or ‘the RC') is a First Nations organization dedicated to supporting First Nations to resume control over their lands, environment and natural resources by providing intergovernmental support, training, resources, information and other support services to First Nations interested or engaged in the Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management. The RC has regionally-specific supports and contacts for First Nations developing and implementing their land codes.

2.2.3 Reserve Land and Environmental Management Program (RLEMP)

RLEMP provides funding to First Nations to develop the capacity needed to exercise increased responsibility over the management of reserve land, resources and environment. RLEMP is available to First Nations operating under the Indian Act. To apply for RLEMP, a First Nation or tribal council must complete and submit a First Nation Entry Request Form and Capacity Self-Assessment exercise to their ISC regional office. Eligible First Nations should have a description of their planned land and environment management activities in place, and intend to hire or procure land management or economic development services. ISC regional offices conduct an assessment of the First Nation's features against RLEMP eligibility criteria and ISC's available program resources. Once the First Nation or tribal council is accepted into RLEMP, they must pass a band council resolution agreeing to the terms of the program.

NALMA is the major service delivery partner in RLEMP. First Nations are also offered support from the Community Lands Directorate at ISC Headquarters and from Regional Offices at ISC to receive land and environment management funding, hire a land manager, access training and development opportunities, and comply with the RLEMP performance measurement requirements.

First Nations receive funding based on their level of responsibility under RLEMP (Training and Development Level, Operational Level or Delegated Authority LevelFootnote 4) and a funding formula. The RLEMP funding formula takes the following factors into consideration: the First Nation's population base; land base; type, volume and complexity of land and natural resources interests (i.e., leases, permits, etc.); operational costs; environmental activities (i.e., environmental site assessments, audits, etc.); and compliance activities. Only registered land and natural resources transactions resulting in an active interest/possession in land will be funded.

2.2.4 First Nations Land Management (FNLM)

In 1991, a group of First Nation Chiefs approached the Government of Canada with a proposal to opt-out of 40 provisions of the Indian Act on land, environment and resources. As a result of this proposal, the Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management was negotiated by 14 First Nations and Canada in 1996 and came into effect in 1999 through the First Nations Land Management Act. Together the Framework Agreement and the First Nations Land Management Act form First Nations Land Management (FNLM). The Framework Agreement recognizes the authority of First Nations to exercise their jurisdiction over the governance and management of their reserve lands, resources and environment according to their own laws, values and priorities while also enabling improved economic development. Following further negotiations between First Nations and Canada, the Framework Agreement now provides the opportunity First Nations to opt-out of 44 land-related sections of the Indian Act relating to land management with their own land code.

Any First Nation with lands reserved for Indians within the meaning of section 91(24) of the Constitution Act of 1867 or with lands set aside in Yukon can opt-in to FNLM. Interested First Nations begin by submitting a Band Council Resolution stating their intent to join. First Nations are provided with funding to develop a land code, conclude an individual agreement and hold a ratification vote in the community. These activities are laid out in a Developmental Phase Funding Agreement (DPFA) and this phase of activity is commonly referred to as the developmental phase. First Nations then work with the RC to develop a land code, and hold a ratification vote in their community. If the vote is successful and the community accepts the new land code, the First Nation moves from the developmental phase into the operational phase. Once the land code comes into effect, land authorities are transferred from ISC and First Nations can then begin to implement their laws under their land code, and have the opportunity to reintegrate linguistic and other traditional concepts of land governance and protection.

The major service delivery partner for FNLM is the RC. Alongside the RC, First Nations are also offered support from the Community Lands Development directorate and Regional Offices at ISC to become a signatory to the Framework Agreement on First Nations Land Management, access federal funding to develop and ratify a land code, and govern reserve lands under their land codes. Natural Resources Canada also plays a significant role in supporting research and land description reports for First Nations.

First Nations who are Operational in FNLM receive funding through a grant model. Funding for developmental activity is provided via contribution agreements that are administered by the RC. Funding is determined at various levels depending on whether a community is in the Developmental or Operational Level of FNLM, and the Operational FNLM funding formula also considers population, land base, and the volume and complexity of a First Nation's registered land and natural resources interests.

2.2.5 Land Use Planning

Land Use Planning provides funding to support First Nations in developing a community-led Land Use Plan. Land Use Plans are primary tools for governing over lands, and the process of developing a Land Use Plan can determine how decisions are made on where houses, parks and schools will be built, and how infrastructure and other essential services will be provided. Since 2018, Land Use Planning implementation has been shifted from ISC regional offices to two delivery partners: the RC and NALMA. Within ISC, funding is flowed through the Community Lands Directorate at Headquarters.

First Nations operating under the Indian Act, including RLEMP communities, are eligible to apply for Land Use Planning funding provided by NALMA. Operational and Developmental FNLM First Nations can apply for Land Use Planning funding provided by RC. Delivery partners are responsible for the intake process, supporting First Nations with the development of their Land Use Plans and providing training opportunities to First Nations.

3. Evaluation Methodology

3.1 Scope and evaluation issues

3.1.1 Evaluation scope

This evaluation covered the years 2014-2015 to 2020-2021 as per Treasury Board requirementsFootnote 5, and selected activities up to the 2021-2022 fiscal year to recognize and provide feedback on impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although not part of the original scope, the evaluation also incorporated more recent data and actions taken by ISC to implement the mandate of the department since its creation in 2017-2018. The evaluation was undertaken to provide a neutral and evidence-based assessment of relevance and performance (effectiveness and efficiency), with a focus on lessons learned and best practices. The evaluation examined these issues through lenses of gender-based analysis plus (GBA Plus), reconciliation, and considered the impacts of climate change. Appendix B shows the approved Terms of Reference for the evaluation, while a more detailed list of specific questions and issues that guided the evaluation is found in Appendix C includes a more detailed list of the specific questions and issues that guided this evaluation.

A mapping exercise to link findings to the lenses of relevance and performance revealed repetition across the responses to the evaluation questions. As such, the findings in this report are presented cohesively in key themes rather than in the traditional relevance/effectiveness/efficiency format. The evaluation team grouped the seventeen major findings thematically based on the ideas that were most present in the information shared with them by evaluation respondents. The eight themes are presented in three groupings.

| Importance of Land | Current Challenges | Ways to Move Forward |

|---|---|---|

| Community and Culture Self-Determination |

Funding Capacity Cross-Cutting Issues |

Relationships Reporting Service Transfer |

3.2 Design and Methods

The evaluation was led by a team from the Evaluation Directorate within ISC. The Methodology Report was finalized in June 2022, with primary data collection occurring from May 2022 to October 2022.

The evaluation relied on a mixed-methods approach that included the following lines of evidence: a document and literature review; interviews with 44 individuals involved in RLEMP, FNLM and Land Use Planning in ISC, First Nations organizations, and First Nations communities; 40 complete responses and 40 partially complete responses from a survey distributed to 401 individuals involved in land management at the First Nation community level; content and feedback from participants of 5 conferences hosted by First Nation Regional Lands Associations (RLAs); 6 community site visits; and an analysis of quantitative administrative data held by the Community Lands Directorate at ISC Headquarters. When discussing the qualitative responses provided by both interviewees and survey respondents, the evaluation team has used a ‘semi-quantification' approach outlined in Table 1 by describing responses based on the frequency each response. For a more detailed breakdown of the methodology see Appendix C.

| Term used | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | A few | Several | Many | Majority | |

| Number of responses | 1 | 2-5 | 6-15 | 16-21 | >22 |

3.3 Limitations

While the evaluation process rigorously sought the views of land management experts, there are some limitations to how this data can be understood and applied broadly. The key limitation of this report resulted from limited engagement with First Nations in select provinces, as the evaluation team travelled to three regions to meet with 18 interviewees from First Nations in communities and conferences. To address this limitation, the evaluation team interviewed 12 representatives from First Nations organizations who had a national understanding of the evaluation's subject matter. A survey was also deployed to collect input from First Nations across all provinces, however it returned a low survey response rate (20%) and a low survey completion rate (10%). Given the particularly low survey response rate from RLEMP First Nations (13%), only quantitative data related to FNLM First Nations survey respondents has been included in the report. Further, given that none of the questions in the survey were mandatory, each quantitative figure given has also included the denominator to show how many responses were gathered for each question. Qualitative responses from the survey have been retained and included throughout the findings. For more information on the limitations and mitigation strategies employed see Appendix C.

3.4 Indigenous Engagement

Indigenous engagement was built into the methodology for this evaluation and includes input at key stages from ISC's main land management service delivery partners: NALMA, and the RC. The RC and NALMA each formed an informal partnership with the evaluation unit to collaborate on several aspects of the evaluation, including: methodology and data collection tools, survey development, community selection and the development of key findings. The evaluation team met virtually with these partner organizations every six to eight weeks to provide updates. The National Indigenous Economic Development Board (NIEDB), a non-political body mandated to provide strategic advice to government, also reviewed and provided comments at the preliminary findings stage of the evaluation.

The evaluation also relied on the regional branches of NALMA to engage with First Nations land managers. Executive Directors of RLAs had the opportunity to review the methodology for the evaluation and provide feedback. Four RLAs were heavily involved in data collection by creating opportunities for their networks to engage in the evaluation, and by facilitating community site visits in their regions.

4. Findings: Importance of Land

4.1 Community and culture

Finding 1: Planning for the future use of land is an important intergenerational aspect of First Nations' community-building

Land is the basis for community development, including economic and social development, and is an important part of many First Nations' cultures.Footnote 6 Access to lands and the natural world helps to preserve First Nations' traditions and cultural practices. Several First Nations interviewees and survey respondents shared that they want their communities and youth to benefit from traditional land-based activities such as hunting and land-based learning.

Planning for the future of their lands is one way that some First Nations are strengthening their community ties. Passing knowledge from one generation to the next is a key practice of many First Nations' cultures, and Land Use Planning is one forum where communities can encourage and facilitate this dialogue. The evaluation team heard from one individual in an RLEMP First Nation that they were able to use their Land Use Plan to help resolve conflict around land use between community members. Several RLEMP and FNLM First Nation interviewees and survey respondents shared that future-oriented land management can create a shared vision to address all facets of well-being in their communities.

"Those are the two souls of First Nations, the language and the land"

Many First Nations interviewees and survey respondents also noted that engaging with a variety of members and their perspectives on land management is important for their First Nations' decision-making processes. These interviewees and respondents shared that they generally tailor their engagement to reach as many of their members as possible, and work to mitigate challenges caused by community factors like engagement fatigue, poor timing, and competing priorities.

The evaluation found that First Nation women are generally engaged in lands processes. Historically across Canada, Indigenous women acted as caretakers of the environment and water.Footnote 7 Today First Nations women are highly involved in First Nations' land management and are estimated at 60% of all First Nations' trained and certified land managers.Footnote 8 An example of how women's participation in decision-making processes is encouraged in First Nations is the placement of one FNLM community's child care centre next to their administration centre. Interviewees from that community shared that they often see or interact with the children throughout the course of their work day, emphasizing the intergenerational nature of their work.

While there is no "one size fits all" approach to engaging people in land management, there are best practices to engage diverse populations within First Nations. The evaluation team heard from land managers that they find it easiest to engage members in a one-on-one setting but stress that adaptability is key to a successful planning process. A few FNLM survey respondents shared they have had to reduce the scale of their community outreach due to staffing shortages in their community. Many Interviewees and survey respondents from First Nations communities are gathering input to their land management processes via a variety of methods tailored for each sub-group:

- Elders and Youth may participate in tailored focus group discussions to identify their priorities for the future;

- Student and volunteer positions are regularly used to engage Youth in land management; and

- Knowledge Transfer sessions in communities enable different groups to learn from each other.

4.2 Self-Determination

Finding 2: Self-determination is an inherent right for First Nations, and there are ways to support communities to exercise that right over their lands and natural resources

The evaluation found that First Nations generally use FNLM, RLEMP and Land Use Planning to exercise their self-determination over their lands and natural resources. Several First Nations interviewees and survey respondents feel that control over land empowers First Nations to address social and economic imperatives, and that land management can support self-determination when it is properly resourced. For several FNLM First Nations, the evaluation team heard that land management is their expression of self-determination. The evaluation team also heard from many FNLM First Nation interviewees and survey respondents that they can make decisions based on their needs once they have a land code in place. They shared that they move "at the speed of business" to develop their lands under their own laws, without going through the federal government's bureaucracy. Interviewees from Operational FNLM First Nations shared that development projects are increasing rapidly and bringing substantial own-source revenues into their communities. This empowers their community to re-invest that revenue in projects that meet their vision for the future.

First Nations want to determine for themselves what success looks like. RLEMP can be a way for First Nations to build land management capacity in their community, but it is not a step in a linear process to any form of self-governance outside of the Indian Act. A few First Nations interviewees view RLEMP as a way to exercise their own self-administration over their lands. A few interviewees from RLEMP First Nations expressed a desire for ISC to re-open the Delegated Authority level of RLEMP as a further measure of their ability to administer and manage their own reserve lands and resources.

The evaluators heard that First Nations are using land management to plan ahead in their communities, and adapting supports and tools to their communities' needs. The evaluation found that First Nations in RLEMP and FNLM are generally using Land Use Plans to set long-term priorities based in their community's vision for the future. Several FNLM First Nations interviewees stated that they are using their land codes to exercise their jurisdiction where possible, such as codifying their traditional values in land codes and grounding their laws in community-based customs. One Operational FNLM First Nation has been documenting Elders' visions of land use in their community since the 1990s and is now ensuring that their present-day land code is aligned with their community's past customs. Their lands department is also conducting impact assessments for new developments which come from a lens aligned with their stewardship of the land, and brings a focus on member's rights to practice their culture.

Not all First Nations feel that the current land management tools support a Nation-to-Nation relationship with Canada. The evaluation team heard from several First Nations interviewees and survey respondents that land management programming under the Indian Act is colonial, and that western styles of land management and leasing may lead to further dispossession of Indigenous land. Rights over lands, territories and natural resources represent a core issue for many Indigenous peoples globally.Footnote 9 The NIEDB's National Indigenous Economic Strategy recognizes this in its Strategic Objective, that Indigenous communities have the right to develop their land for the purposes of building sustainable economies.Footnote 10 A few First Nations interviewees spoke of changing the current structures to better reflect their cultural perspectives rather than simply ‘Indigenizing' western systems of land ownership. One First Nation interviewee suggested that fully implementing the United Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is one way that Canada could work with First Nations to decolonize its structures and processes.

5. Findings: Current Challenges

5.1 Funding

Finding 3: There are disparities in funding access and distribution across and within RLEMP, FNLM and Land Use Planning that create differences in opportunities for First Nations to benefit from their lands and natural resources

The evaluation found that land management funding is disparate across Canada. The funding formula for RLEMP has not been updated since its creation in 2005, and the FNLM formula has not been updated since 2018-19 based off of its five-year negotiation cycle. These formulas do not reflect current inflation rates in Canada. Further, the formulas are standardized nationally and have differential impacts depending on location. For example, the cost of fuel differs between province or territory, and communities may have different costs associated with land management based on their unique contexts. While understanding that there are key differences in these initiatives (e.g., the full transfer of jurisdiction and liability under FNLM) and their relative funding amounts, there are foundational funding differences between the core formulas for FNLM and RLEMP, particularly that the RLEMP formula does not include a base or minimum level of funding to support core land management.

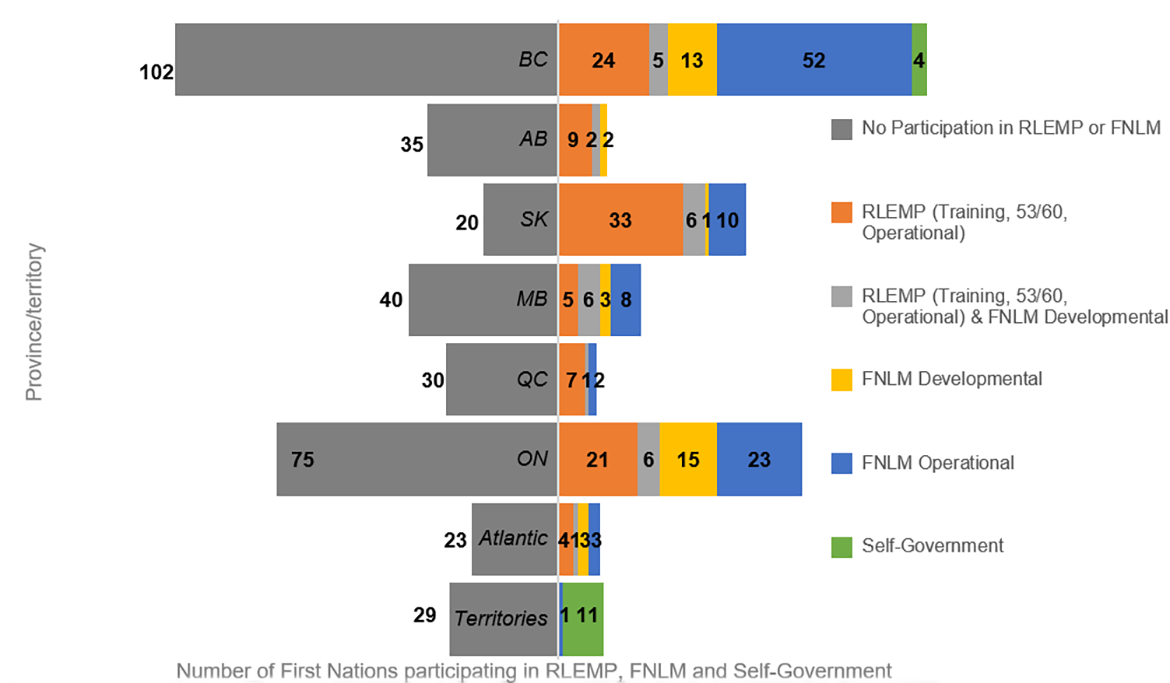

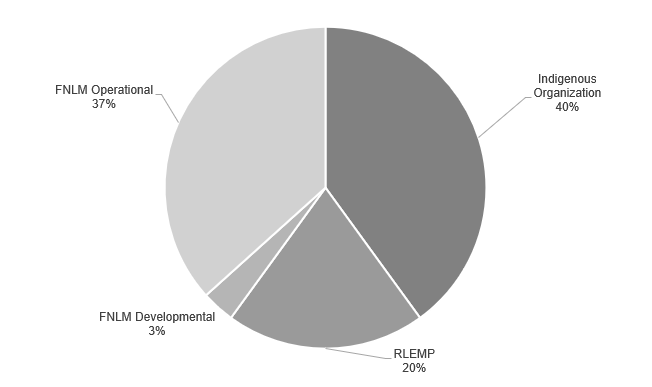

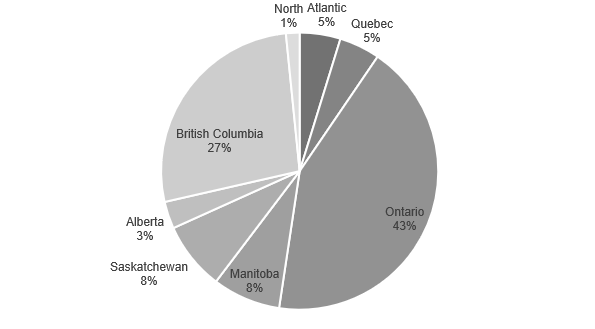

In addition to funding differences between FNLM and RLEMP, the uptake from First Nations varies by community size and region. The evaluation found that some smaller First Nations will require additional support, such as additional human and financial resources, to build capacity and equity. For example, 73% of First Nations with a land base of less than 1000 hectares are not involved with FNLM or RLEMP, and just 19% of small First Nations have a Land Use PlanFootnote 11. As well, communities with smaller land bases are less likely to subscribe to RLEMP, though this does not apply for FNLM. Figure 1Footnote 12 is the geographic distribution of First Nations participating in land management and shows that more than half (58%) of the 635 federally-recognized First Nations in Canada do not currently participate in RLEMP or FNLM. As a community's land base impacts their participation in RLEMP but not FNLM, consideration should be given to additional pre-readiness supports to facilitate entry into RLEMP, such as additional funding for small communities, or an expansion of the eligibility criteria.Footnote 13. A few ISC staff interviewees expressed frustration in not being able to provide predictable, dedicated funding for land management activities to First Nations communities in northern territories who do not have federally-recognized reserve lands.

Data Source: Community Lands Development, ISC, as of May 2022.

Text alternative for First Nation Participation in RLEMP, FNLM and Self-Government by Region (n=635)

Figure 1 shows the geographic distribution of First Nations participating in RLEMP, FNLM and self-government by province. In B.C there are 102 First Nations not participating in RLEMP or FNLM; 24 First Nations in RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational); 5 First Nations in both RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational) and Developmental FNLM; 13 First Nations in Developmental FNLM; 52 First Nations in Operational FNLM; and 4 First Nations in self-government.

In Alberta, there are 35 First Nations not participating in RLEMP or FNLM; 9 First Nations in RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational); 2 First Nations in both RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational) and Developmental FNLM; 2 First Nations in Developmental FNLM; 0 First Nations in Operational FNLM; and 0 First Nations in self-government.

In Saskatchewan, there are 20 First Nations not participating in RLEMP or FNLM; 33 First Nations in RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational); 6 First Nations in both RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational) and Developmental FNLM; 1 First Nations in Developmental FNLM; 10 First Nations in Operational FNLM; and 0 First Nations in self-government.

In Manitoba, there are 40 First Nations not participating in RLEMP or FNLM; 5 First Nations in RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational); 6 First Nations in both RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational) and Developmental FNLM; 3 First Nations in Developmental FNLM; 8 First Nations in Operational FNLM; and 0 First Nations in self-government.

In Québec, there are 30 First Nations not participating in RLEMP or FNLM; 7 First Nations in RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational); 1 First Nations in both RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational) and Developmental FNLM; 1 First Nations in Operational FNLM; and 0 First Nations in self-government.

In Ontario, there are 75 First Nations not participating in RLEMP or FNLM; 21 First Nations in RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational); 6 First Nations in both RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational) and Developmental FNLM; 15 First Nations in Developmental FNLM; 23 First Nations in Operational FNLM; and 0 First Nations in self-government.

In the Atlantic, there are 23 First Nations not participating in RLEMP or FNLM; 4 First Nations in RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational); 1 First Nations in both RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational) and Developmental FNLM; 3 First Nations in Developmental FNLM; 3 First Nations in Operational FNLM; and 0 First Nations in self-government.

In the Territories, there are 29 First Nations not participating in RLEMP or FNLM; 0 First Nations in RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational); 0 First Nations in both RLEMP (Training, 53/60 and Operational) and Developmental FNLM; 0 First Nations in Developmental FNLM; 1 First Nations in Operational FNLM; and 11 First Nations in self-government.

"Funding is key in offering a greater future, like we're trying to do… if funding keeps coming in, good things are going to come from it."

For those First Nations who do participate in RLEMP or FNLM, funding inequality exists within and across the offerings. Since 2018, Land Use Planning is delivered through NALMA and the RC rather than ISC, and both NALMA and the RC have different approaches and funding agreements in place for this service area. The funding formulas for both FNLMFootnote 14 and RLEMPFootnote 15 consider the volume and complexity of a First Nations' land transactions, although FNLM Operational funding has a minimum core funding amount along with set categories. This can create disparities, as a community with few members but many land transactions could receive significantly more funding per person than a community with a large population but fewer lands transactions.

Access to RLEMP is another challenge, as interested First Nations cannot always enter the program as availability and participation is determined by the national budget. The evaluation team heard from several ISC staff interviewees that RLEMP is oversubscribed and cannot fund new entrants until current RLEMP First Nations exit the program for FNLM or self-government. This makes it difficult for ISC regional offices to promote RLEMP to communities who are looking for land management supports. More than half of First Nations with a ratified land code (54 out of 99Footnote 16) first built their land management capacity under RLEMP, which may point to the importance of building up community capacity for the next cohort of self-governing First Nations.

The evaluation found that current ISC funding for land management is not providing First Nations with the ability to undertake planned activities in managing their own lands. Many First Nation interviewees and survey respondents express a desire for more land management responsibilities but do not have sufficient funding to do so. These responsibilities can include land-related economic development initiatives, and environmental management and protections. A few ISC staff interviewees and one First Nations interviewee under RLEMP told the evaluation team that mapping is a ‘key cornerstone of land management' and that RLEMP First Nations could expand their land management operations, such as surveying and leasing their land, if additional investments were made in training and support for geographic information systems (GIS). Several First Nation interviewees from communities that are Operational under FNLM shared that additional funding support would allow them to develop their own legal orders and practice effective land governance, as well as prepare themselves for unseen expenses related to legal challenges to their land codes.

To supplement their existing land management funding, First Nations access other ISC supports. For example, the Lands and Economic Development Services Program (LEDSP) is viewed as a helpful support for one RLEMP First Nation as they work toward their goal of becoming self-sufficient. However, while LEDSP does have a core operational funding formula, the aspect of LEDSP discussed by interviewees is application-based, encompasses a broader scope than land management, and is not guaranteed funding for First Nations undertaking land-related projects. Additionally, a few FNLM First Nations interviewees shared that they have sought funding for lands projects outside of ISC, either from other federal departments or provincial governments.

"Our core need is the funding and flexibility to build capacity and undertake projects in the way [that works] best for us. Every First Nation is different, with different needs and capabilities. We have exceptional leadership and a highly educated workforce with a strong community focus on economic development. Other communities have different priorities and capacities."

The evaluation found that First Nations communities and organizations need predictable funding arrangements, and that First Nations interviewees and survey respondents view the flexibility of moving funding and using it as needed as critical to effective land management in communities. The evaluation team heard from ISC staff interviewees that they have tried to exercise flexibility in funding agreements with partner organizations in the Lands sector, by ensuring there is a process for moving funds between budget line categories, and by supporting partners to use surplus funding to respond to the real needs in communities as they arise. First Nations interviewees and survey respondents indicated that similar flexibilities at the community level are beneficial to their work in land management.

First Nations interviewees and survey respondents indicated they would benefit from more predictable funding in more holistic land management supports, such as funding for Environmental Site Assessments and for LEDSP at ISC. A few First Nations interviewees in FNLM indicated that block funding agreements would best suit their needs, and allow them to plan and execute their lands projects strategically, while grounding them in community need rather than available funding. Several ISC staff interviewees and one interviewee from an RLEMP First Nation suggested that ISC could implement flexible funding arrangements so First Nations can address their communities' land management priorities.

"We need help to build up capacity. We also need a land use plan. However, how can we get help if we don't know where to start? It's good to do things in our ways. Yet we need guidance."

First Nations have varying capacities to identify and apply for time-limited funding opportunities. While some First Nations are able to hire a consultant to support them in writing proposals, they may lose that background knowledge and related documents when the contract ends. Not all First Nations have the in-house capacity to identify funding opportunities and write proposals for complicated and time-limited land management supports. Several First Nations under FNLM and RLEMP indicated that they would benefit from assistance to access additional land management supports, such as LEDSP and Land Use Planning, by ensuring that funding opportunities are communicated to communities, and that funding deadlines be extended to allow sufficient time to access opportunities.

Finding 4: Funding for First Nations Land Management (FNLM) is seen as efficient

In 2018 ISC implemented new Terms and Conditions for direct funding from ISC to FNLM operational communities, and changed the funding approach from a contribution agreement to a grant model.Footnote 17 ISC staff interviewees indicated the new grant approach is working well. Survey respondents from FNLM Operational communities (n=31) were split on whether they are able to access lands funding predictably and consistently – approximately half said they could, and half said they could not. This is in contrast to the 83% (n=6) of survey respondents from FNLM Developmental communities who shared they could not access lands funding in a predictable and consistent manner. As funding is delivered via contribution agreements during the developmental phase, and via a grant agreement once a First Nation has a ratified land code, these findings could speak to the total lands funding for a community rather than specifically to the funding under FNLM. Several interviewees from both FNLM and RLEMP First Nations shared that knowing how much they will receive from ISC in advance allows them to forecast their budget and plan lands projects strategically.

"And so funding is incredibly important for [land tenure and land use planning] because they take so many resources and they require so much time and resources from people. They're not really built into our normal processes. That's something that we really struggle with even the operational funding that we receive. To develop laws with that amount of funding is impossible."

Some First Nations interviewees and survey respondents did not feel ISC's contributions to the FNLM operational funding formula are always adequate to meet the needs of their communities, particularly around environmental protections, law development, and enforcement of land codes.Footnote 18 ISC provides the RC with additional project-based funding for FNLM communities that may address these areas, however the evaluation team heard from a few FNLM First Nations interviewees who still find project-based funding criteria and timelines too strict. A few interviewees from FNLM First Nations who have had operational land codes for a number of years and have the ability to generate own-source revenue felt they were able to operate their Lands Departments effectively, though one interviewee from a small FNLM First Nation speculated that their community may be too small to reach the self-sufficiency funding levels they desire.

Finding 5: Stable funding arrangements would better support long-term land use planning projects

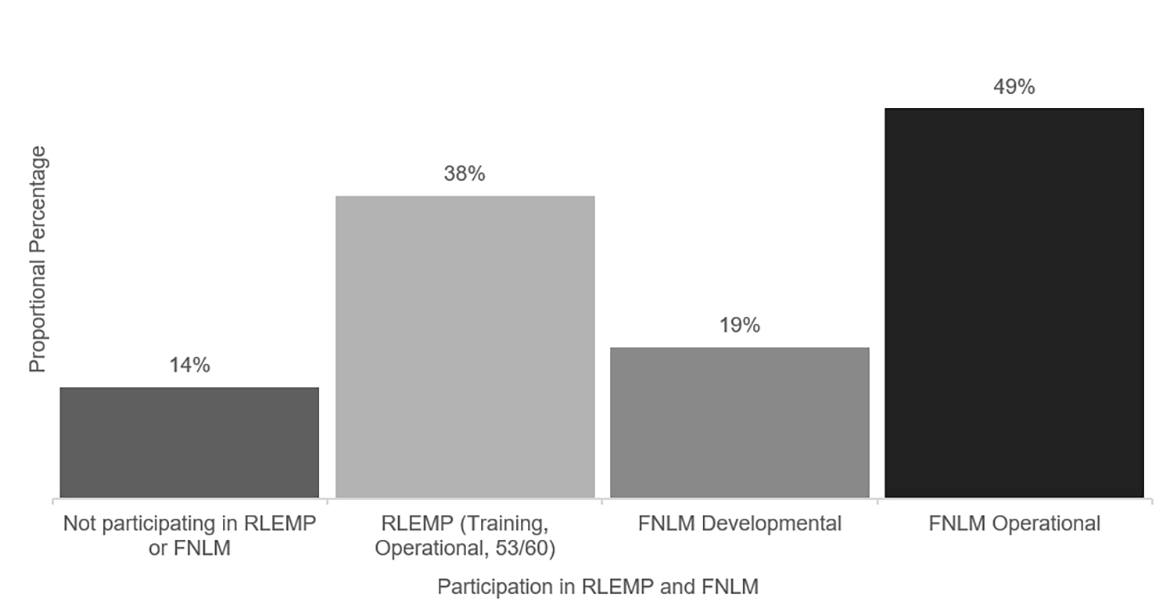

The evaluation found that Land Use Planning would benefit from predictable and multi-year funding arrangements so First Nations organizations can have consistent call-outs, make timely funding decisions, and support First Nations to implement their developed Land Use Plans. One interviewee from a First Nations organization expressed concern around the disparity of funds earmarked for Land Use Planning for First Nations under the Indian Act or FNLM. As shown in Figure 2, First Nations who participate in either RLEMP or FNLM were more likely than other First Nations to have a land use plan. A larger percentage of FNLM Developmental communities that participated in RLEMP have a land use plan compared to those that did not participate in RLEMP, which could correlate with the success of RLEMP in building land management capacity, though this cannot be proven definitively and could be a function of having increased access to regional officesFootnote 19 or First Nations organizations, or otherwise having more capacity, experience or expertise in land management before entering into RLEMP.

Data source: Community Lands Development, ISC as of May 2022

Text alternative for Proportional Percentage of First Nations with a Land Use Plan by Participation in RLEMP and FNLM (n=635)

Figure 2 shows the proportional percentage of First Nations with a Land Use Plan by Participation in RLEMP and FNLM (n=635). 14% of First Nations with a Land Use Plan are not participating in RLEMP or FNLM; 38% of First Nations with a Land Use Plan participate in RLEMP (Training, Operational, 53/60); 19% of First Nations with a Land Use Plan participate in FNLM Developmental; and 49% of First Nations with a Land use Plan participate in FNLM Operational.

Since 2018, Land Use Planning for First Nations under the Indian Act is delivered through NALMA. While the 2017 and 2018 Federal Budgets provided additional funds for Land Use Planning, the evaluation team heard from a few ISC staff and several First Nations interviewees that the funding has not always been predictable year-over-year. The initial funding for Land Use Planning under the Indian Act was disbursed as a one-year agreement, and the evaluators heard that it was a challenge for NALMA to plan ahead and organize effective call-outs without confirmation of the next year's funding. NALMA and ISC have since agreed to a multi-year funding agreement from April 2019 to March 2023 that outlines NALMA's funding requirements for land use planning over this period. A few interviewees from First Nations organizations and communities shared that Land Use Planning is a long-term community project involving extensive engagement with community members, and annual funding arrangements create some uncertainty around the next year's land use planning activities.

Since 2018 First Nations within FNLM access funding and support to develop and implement Land Use Plans from the RC. The RC has a three-year funding budget for Land Use Planning and supports communities by accepting applications and by assessing the need for that community. Land use plans developed under the Indian Act may need to be revised to account for the new statutory environment once a community becomes signatory to the Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management. Given the changed legislative backdrop once a community ratifies their land code and individual agreement, First Nations with an operational land code are prioritized for the RC's Land Use Planning supports.

"There are 129 participants in the Reserve Land and Environment Management Program. Some of these communities get as little as $8000 a year, or less, to offset costs of a land manager and to administer a Land Management Office."

Across Land Use Planning, the evaluation team found a general consensus from ISC staff, First Nation organization, FNLM community and RLEMP community interviewees that First Nations need support to implement their completed Land Use Plans, and that this is an area for improvement. One interviewee from a First Nation noted that, while the Land Use Planning process can be a good tool to gather community members together and agree on a vision for their land priorities, without support or resources to implement the plan, it can lie idle rather than act as a guiding tool for future development.

Finding 6: Current Reserve Land and Environment Management Program (RLEMP) funding is inadequate to meet its objectives

The evaluation found that for communities in RLEMP, current funding does not adequately prepare First Nations for developing capacity in terms of land management. Several First Nations and a majority of ISC staff interviewees shared that this capacity-building component of RLEMP is falling short of its expected outcomes due to a lack of funding. ISC staff interviewees shared that RLEMP is currently in a funding deficit and cannot support new initiatives by partner organizations or new communities in the program. The evaluation team heard from ISC and First Nations interviewees that core funding is needed to ensure that capacity for land management is strengthened under RLEMP.

The evaluation team heard that many communities under RLEMP are unable to operate a fully-staffed Lands Department. Several RLEMP First Nations interviewees expressed some frustration that the funding they receive from ISC for land management is not sufficient to both staff their Lands offices and undertake lands projects. For example, one RLEMP First Nation interviewee shared with the evaluation team that they had enough funding to cover the salary of their land manager, but not enough to cover the cost for fuel when the land manager needs to inspect parcels of land in the community. In this case, funding had to be used from other sources within the community outside of the Lands department. Other RLEMP interviewees shared that they are unable to advance their own economic development as they could not fund a land manager's salary based on what they receive from ISC, and therefore were finding it difficult to designate land in the Indian Land Registry System (ILRS)Footnote 20. Despite these challenges, the evaluation heard from First Nations that they are using what they receive from ISC under RLEMP to advance as many land management priorities as they can in their communities, and leaning on other supports to address shortfalls. At a national level, the evaluation found that ISC continues to work to find efficiencies and offer additional funds to service delivery partners like NALMA, when available.

Finding 7: The RLEMP funding formula does not reflect the land management reality of many First Nations

"The RLEMP formula has not been updated in years. Some First Nations have a mortgage program [but] there's no funding for registering these."

The evaluation team heard from ISC staff and First Nations interviewees that the RLEMP funding formula is too transaction-focused and may not account for many land management activities that communities undertake. Several RLEMP First Nations interviewees noted that they would like to see a funding approach that is less focused on the Indian Act and provides a sustainable level of funding which acknowledges more comprehensive approaches to land management. Due to its focus on the ILRS, the current RLEMP funding formula may not adequately recognize the unique challenges of the land base of many communities, including remoteness; distribution of reserve lands across large areas with non-reserve land between parcels; and traditional territory which is not registered in the ILRS but is still managed by the community.

While the formula does consider community size, allocating funding based on acreage and population can put small communities at a disadvantage. RLEMP First Nations have identified a need for a revised funding formula that provides a core or base amount of funding, which can be used flexibly to meet community needs.Footnote 21 Other components of an ideal funding formula noted include support for environmental management, enforcement of leases or by-laws, salary provisions for Lands staff beyond a land manager such as clerks and environmental protection officers, recognition of the work that is done off reserve in traditional territories, and additional funding for training or professional development.

5.2 Capacity

Finding 8: An appropriately-compensated and dedicated land manager is vital to ensure First Nations' lands and natural resources are sustainably managed

"We miss a great deal of [funding] opportunities due to a lack of resources in community. Day to day operations take priority over longer term goals and objectives - making full land code implementation slow. Staffing continues to be a problem (both from a funding perspective as well as finding personnel), which means gaps in the community's ability to consistently manage lands and relationships with other governments."

Across FNLM and RLEMP, the evaluation found that land management activities only receive the necessary support and attention when First Nations have a dedicated land manager. Many First Nations interviewees and survey respondents cite recruitment and retention in First Nations' lands offices as an ongoing challenge. First Nations land managers are in high demand and require a specialized and technical skillset, and a few First Nations interviewees shared they experience high rates of turnover in these positions. 82% of FNLM survey respondents (n=50) said there was no succession plan in place for their land manager's retirement, and 64% did not have a training or operational manual for this position, highlighting the disruption that frequent turnover can have for remaining staff or an incoming land manager.

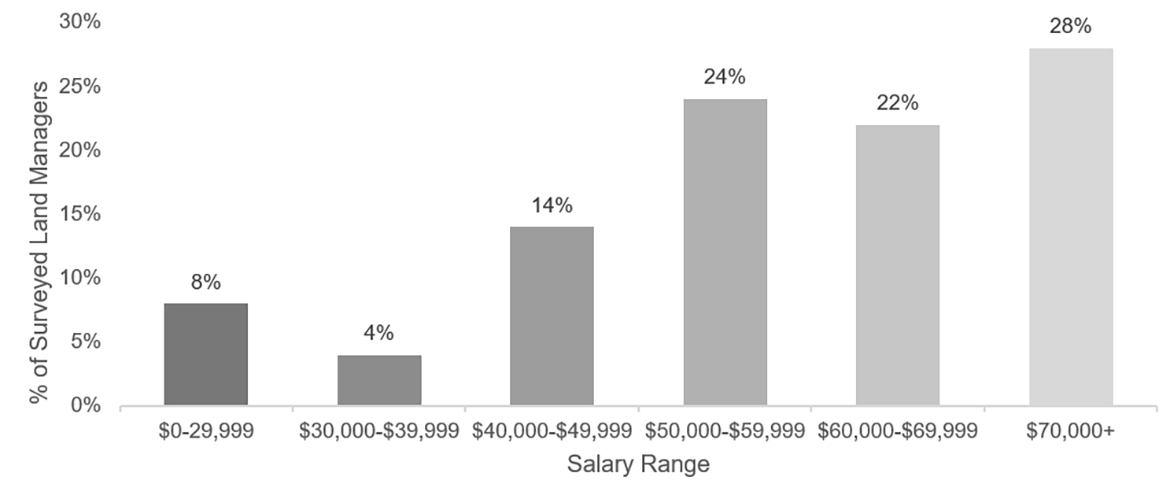

Recruiting land managers can be a challenge due to compensation restraints and the remoteness of many First Nations communities. Figure 3 below shows that for Developmental and Operational FNLM First Nations, 8% of land managers surveyed reported that they earn less than the federal minimum wageFootnote 22, and a further 4% earn just over this amount.

Data source: Community Lands Development, ISC as of May 2022

Text alternative for Salary Range of FNLM Land Managers Surveyed (n=50)

Figure 3 shows the salary range of FNLM Land Managers surveyed (n=50). 8% had a salary range fall between $0 to 29,999; 4% had a range of $30,000 to 39,999; 14% had a range of $40,000 to 49,999; 24% had a range of $50,000 to 59,999; 22% had a range of $60,000 to 69,999; and 28% had $70,000 plus.

A few First Nations interviewees under RLEMP shared that they do have land management activities but do not have a land manager. These interviewees shared that it can be a challenge to keep community members engaged when land management is not a top priority, and that without a dedicated land manager, they were not able to receive support from ISC for their lands-related activities as there was no one in their community who knew who to contact for guidance.

While some First Nations interviewees felt they are accomplishing their land management priorities in either RLEMP or FNLM, the evaluation team heard from many First Nations and a few ISC interviewees that capacity to manage lands effectively can be a challenge. For example, First Nations have varying levels of capacity for land management based on their staff's expertise with lands processes and competing priorities in their community. A few First Nations survey respondents cited leases and permits as the most challenging areas to manage, while several others felt that land designations, land transfers and permits were areas working well for land management in their community.

In both RLEMP and FNLM communities, First Nations interviewees shared that ISC may not be considering communities' in-house capacity to deliver on projects. For example, with the FNLM Enforcement Pilot Project, one FNLM community interviewee told the evaluation team they had to combine the salary dollars provided from the RC for the enforcement position with another available posting in their community to find a candidate. In another FNLM community, some interviewees viewed project-based salary funding as problematic since current staff within the community were being paid much less than what the new position would offer. The evaluation found that some FNLM First Nations are hiring consultants to lead land management efforts as an interim measure, though this does not address their underlying challenges. In RLEMP communities, several land managers recognized that to be self-sustaining, they would need the ability to appropriately compensate their entire lands department, from land managers, to environmental officers, to mediators. One former RLEMP land manager characterized the program as a "double edged sword" given the additional responsibilities that were expected of them while they received insufficient support from ISC to hire more staff in their Lands office.

The portfolio of a land manager varies across First Nations, and Lands staff in both RLEMP and FNLM First Nations face competing priorities in their communities. While some land managers specialize only in lands, many interviewees from both RLEMP and FNLM communities shared that the land manager's portfolios can span multiple departments, including environmental management, laws/law-making, band administration, treaty consultation, membership, estates, and more. Just under half (19 of 48, or 40%) of FNLM survey respondents officially fill other roles in their community in addition to being the land manager. These respondents shared that they have large workloads to deliver on and limited time to attend to 'side of desk' projects (e.g., succession planning, economic development, and environmental protections.). Several FNLM and RLEMP interviewees shared they have just one person working in their Lands office and this can stall progress on their projects if more urgent priorities emerge. One FNLM Lands Director told the evaluation team that even if the community could hire additional staff, they could not all focus on lands due to other priorities within their community.

Finding 9: First Nations and their non-Indigenous partners in the Lands sector could benefit from expanded training

For FNLM and RLEMP First Nations, land governance training is provided by NALMA and the RC, as per ISC's agreements with these partner organizations. Generally, the evaluation team heard that First Nations organizations are well-positioned to provide land management training for First Nations. At a national level, the RC and NALMA provide guidance and tools for land management activities, including on-the-ground training. NALMA has partnered with universities to deliver training on managing reserve lands under the Indian Act,Footnote 23 and the RC has a library of webinars, workshops and other resources available to First Nations under FNLM.Footnote 24 Furthermore, region-specific support is delivered through RLAs for First Nations managing lands under the Indian Act, and through the RC's regional support services for developmental and operational FNLM First Nations. The evaluation team heard from many First Nations interviewees and survey respondents that both the RC and NALMA/RLAs are seen as valuable training partners.

First Nations' reserve land has a unique nature and legal status as compared to other lands in Canada. First Nations interviewees in both RLEMP and FNLM communities discussed land management training as a high area of need for communities, non-Indigenous partners, and governments. For communities, a few RLEMP First Nations interviewees stressed the importance of building up capacity to manage their lands with the continued protection of Canada, and many FNLM First Nations interviewees highlighted a need for support to navigate the new legal contexts of having their own land codes. In response to a survey question asking about support received from ISC, just 12% (n=33) of FNLM First Nation survey respondents felt the support they receive for training is adequate. Interviewees and survey respondents from First Nations in both RLEMP and FNLM shared the value of First Nations organizations in developing and delivering land management training, and the importance of spending time to ‘ramp up' land management activities in communities by both training current staff and recruiting new staff with the right skills and knowledge.

The evaluation found a desire from some First Nations for more specialized or practical training opportunities, which can include additional training on transitioning from land management under the Indian Act to FNLM, navigating Canada's complex legal landscape, additional training on registering lands into the ILRS, and more practical, hands-on opportunities.Footnote 25 The NIEDB's National Indigenous Economic Strategy prioritizes training and development in its Strategic Objective that Indigenous communities have the tools, resources and knowledge to manage their jurisdiction over their traditional lands and territories.Footnote 26 While several FNLM First Nations interviewees were satisfied with the professional development opportunities provided to them through the RC, a few others had difficulty finding the appropriate learning opportunities to suit their unique context and needs. A few First Nations interviewees and survey respondents under FNLM and RLEMP desire additional promotion of the various training opportunities available to them. To offer these increased services, First Nation partner organizations may require additional funding.

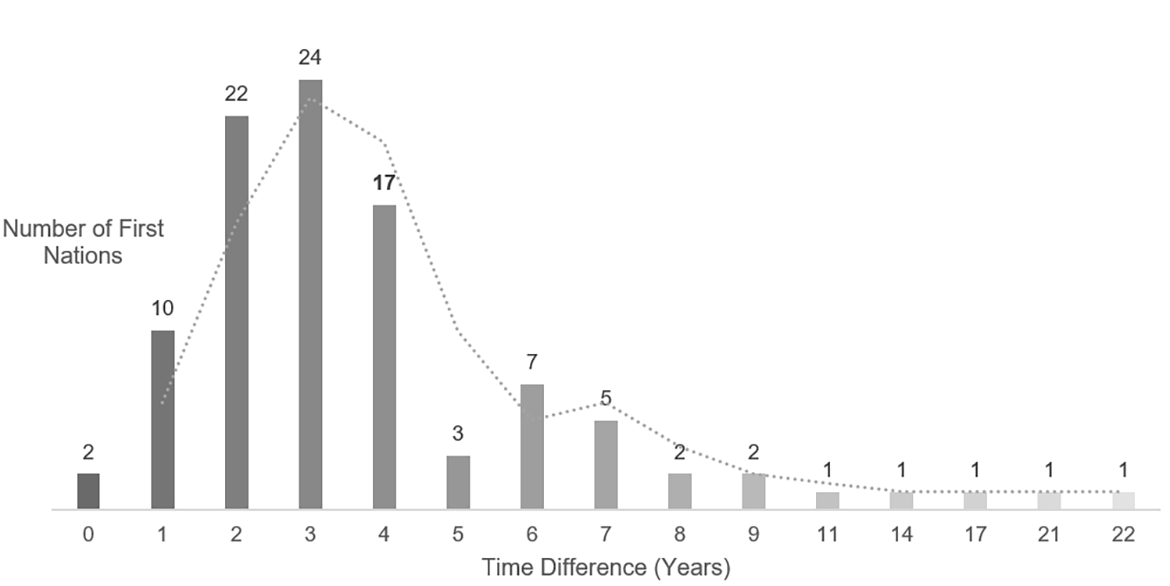

Several RLEMP and FNLM First Nations interviewees expressed a desire for more time and support in the developmental phase to effectively transition into FNLM. Figure 4 shows that it most commonly takes a First Nation three years after signing the Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management to become Operational.

Data source: Community Lands Development, ISC as of May 2022

Text alternative for Count of Rounded Years Between FNLM Signature Date and Operational Date (n=99)

Figure 4 shows a count of rounded years between FNLM signature date and operational date (n=99). Year 0 had 2 First Nations; year 1 had 10; year 2 had 22, year 3 had 24; year 4 had 17; year 5 had 3; year 5 had 7; year 6 had 7; year 7 had 5; year 8 and 9 both had 2; and years 11, 14, 17, 21 and 22 all had 1.

A few interviewees from RLEMP communities suggested the NALMA-run Professional Land Manager Certification Program (PLMCP) could be expanded to include more training on what occurs during the transition from managing lands under the Indian Act to FNLM. Though the focus of the PLMCP is on managing reserve lands under the Indian Act, some land managers shared that the training could still be beneficial to First Nations who do not participate in RLEMP.

"We call upon federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal governments to provide education to public servants on the history of Aboriginal peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal–Crown relations. This will require skills based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism."