An update on the socio-economic gaps between Indigenous Peoples and the non-Indigenous population in Canada: Highlights from the 2021 Census

A Compendium Report to the Department's 2023 Annual Report to Parliament.

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Method

- Findings

- Income – Median individual income

- Low-income measure after tax

- Employment rate

- Employment income

- Education – having at least a high school credential

- Education – completion of a university degree

- Housing – Crowding

- Housing – Dwellings in need of major repair

- Children in foster care

- Indigenous language knowledge

- Justice – Incarceration

- A focus on urban settings

- Conclusions

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

List of tables

- Table 1: Comparison of the gap in median income 2015 to 2020 (adjusted), Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Table 2: Comparison of the gap in median individual income, 2015 to 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada (Five-Year Change)

- Table 3: Number of people living in a low-income situation, 2015 to 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

- Table 4: Comparison of the gap in the percentage living in a low-income situation 2015 to 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

- Table 5: Comparison of the gap in percentage living in a low–income situation 2015 to 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, by gender, Canada (Five-Year Change)

- Table 6: Number of individuals employed, 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Table 7: Comparison of the gap in employment rate 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Table 8: Comparison of the gap in employment rate 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada (Five-Year Change)

- Table 9: Comparison of median employment income (adjusted) 2015 to 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Table 10: Comparison of median employment income 2015 to 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous Populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada (Five-Year Change)

- Table 11: Number of people with at least a high school credential, 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Table 12: Comparison of the percentage of people with at least a high school credential 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Table 13: Comparison of the gap in the percentage of pepole with at least a high school credential 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada (Five-Year Change)

- Table 14: Number of people with a university degree, 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Table 15: Comparison of the gap in the percentage of people with a university degree 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Table 16: Comparison of the percentage with a university degree 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada (Five-Year Change)

- Table 17: Number of households residing in a dwelling classified as crowded, 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

- Table 18: Comparison of the percentage of dwellings classified as crowded 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

- Table 19: Number of households residing in dwellings in need of major repair, 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

- Table 20: Comparison of the percentage of dwellings in need of major repair 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

- Table 21: Number of Indigenous and non-Indigenous children comprising the total population of children aged 0 to 17 in foster care, 2016 to 2021, Canada

- Table 22: Comparison of the percentage of children aged 0 to 17 in foster care, 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

- Table 23: Number of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people capable of holding a conversation in an Indigenous language, 2016 to 2021, Canada

- Table 24: Number of custody admissions of individuals with Indigenous and non-Indigenous identity, 2016 to 2017 to 2020 to 2021, Canada

- Table 25: Comparison of the employment rate, 2016 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, urban areas, Canada

- Table 26: Summary of the size and direction of the change in gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations from 2016 to 2021 for all domains, Canada

List of figures

- Figure 1: Distribution and number of Indigenous people in Canada by province and territory, 2021

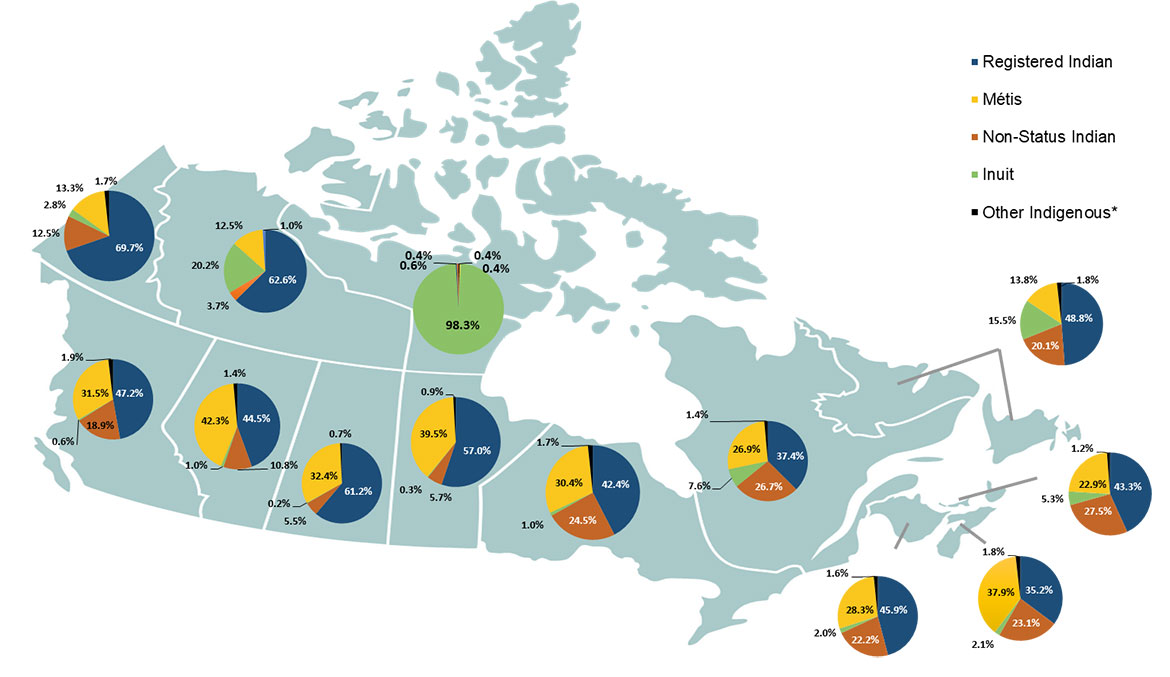

- Figure 2: Composition of the Indigenous population in Canada by province and territory, 2021

- Figure 3: Median individual income, 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Figure 4: Median individual income 2005 to 2020 (adjusted), Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Figure 5: Median individual income, 2020, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

- Figure 6: Median individual income, 2020, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

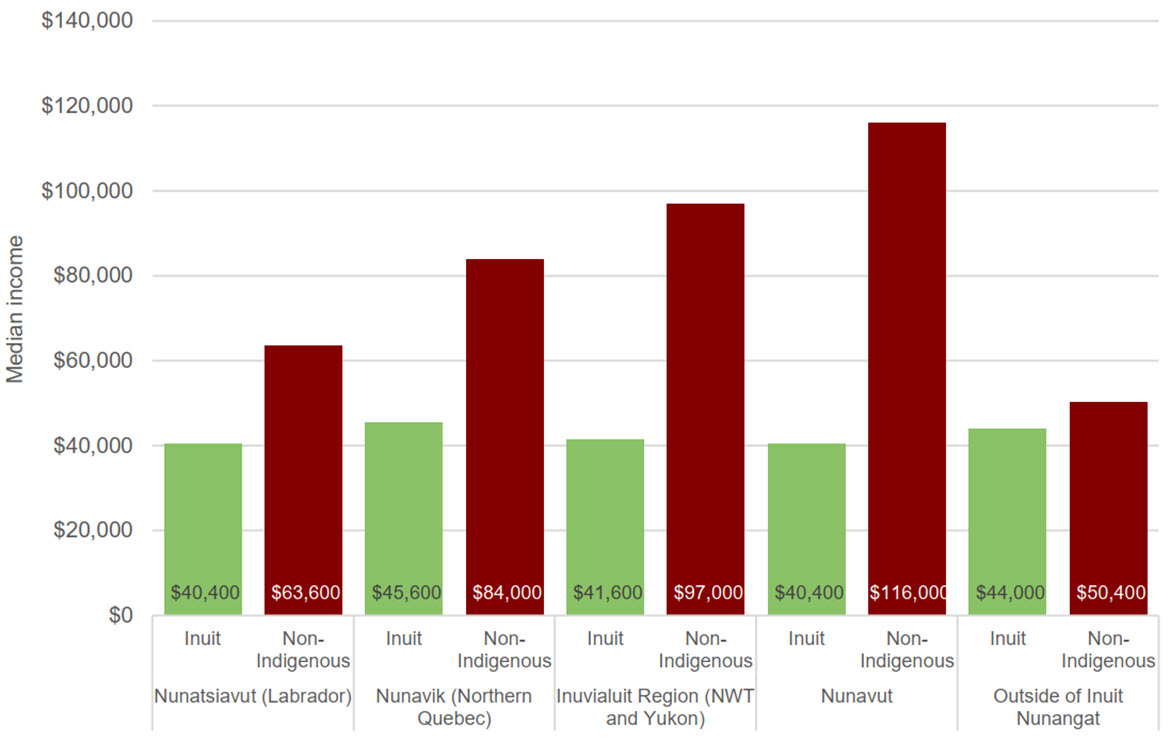

- Figure 7: Median individual income, 2020, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by Inuit region

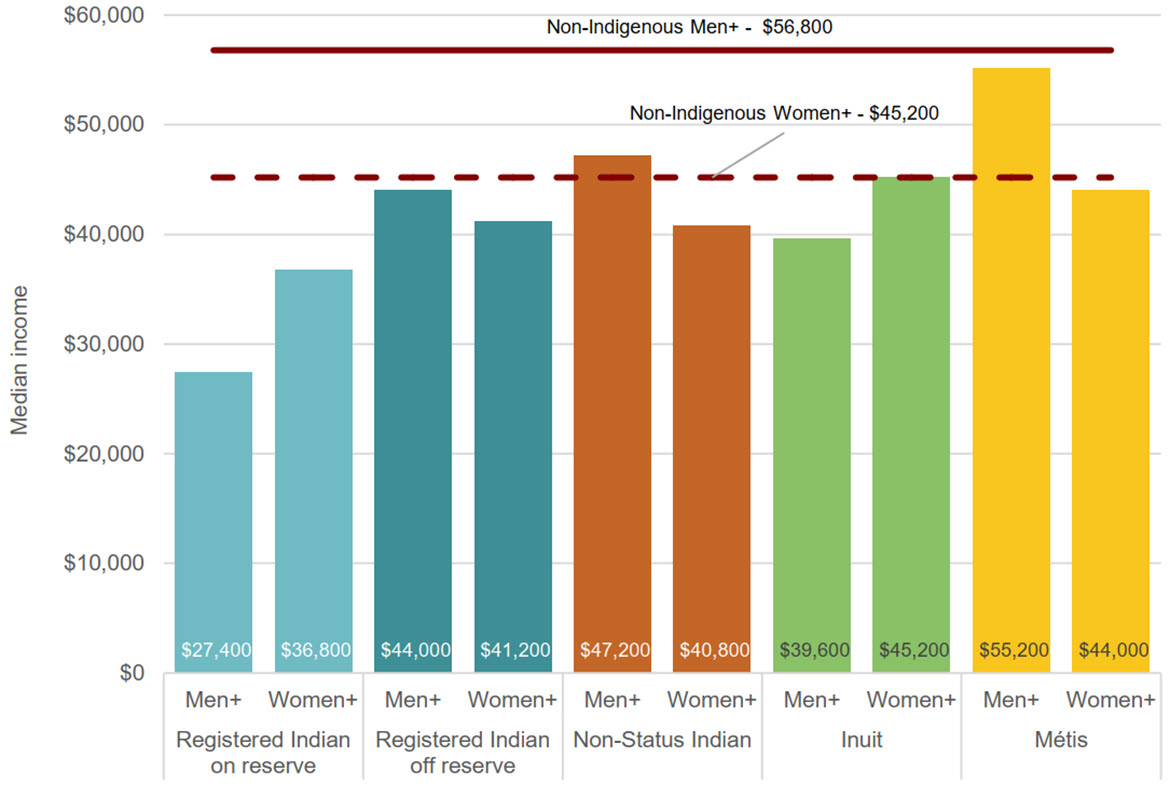

- Figure 8: Median individual income, 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada

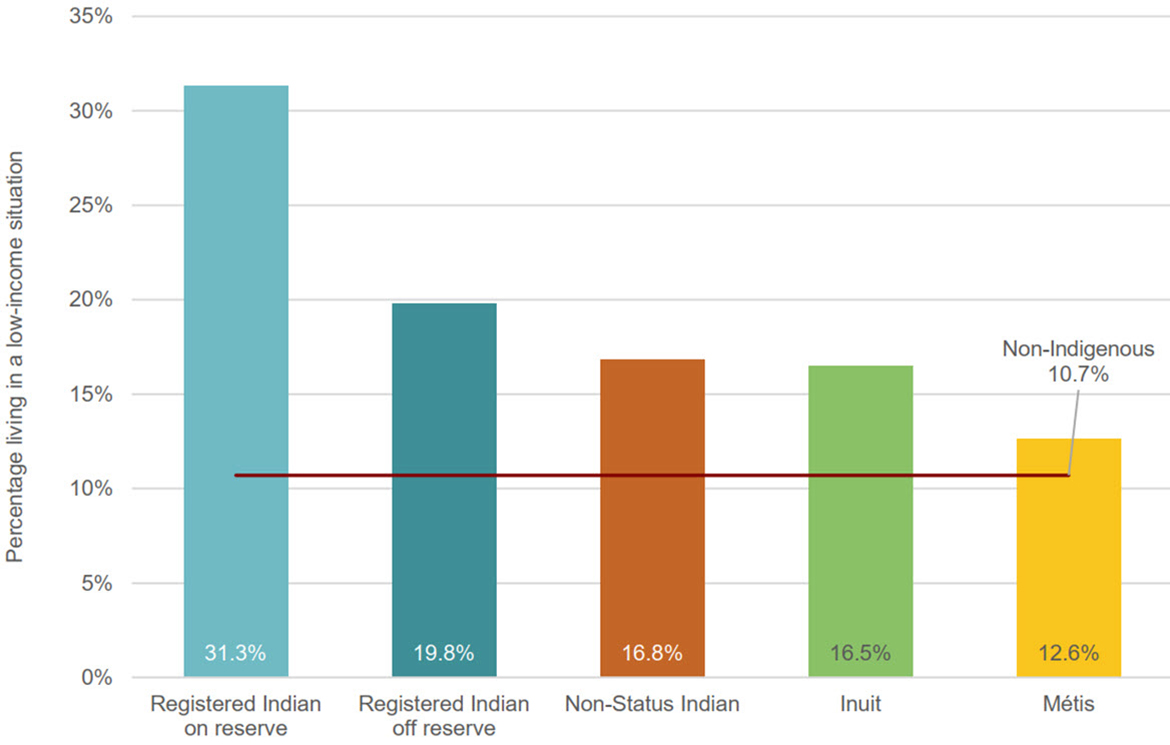

- Figure 9: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

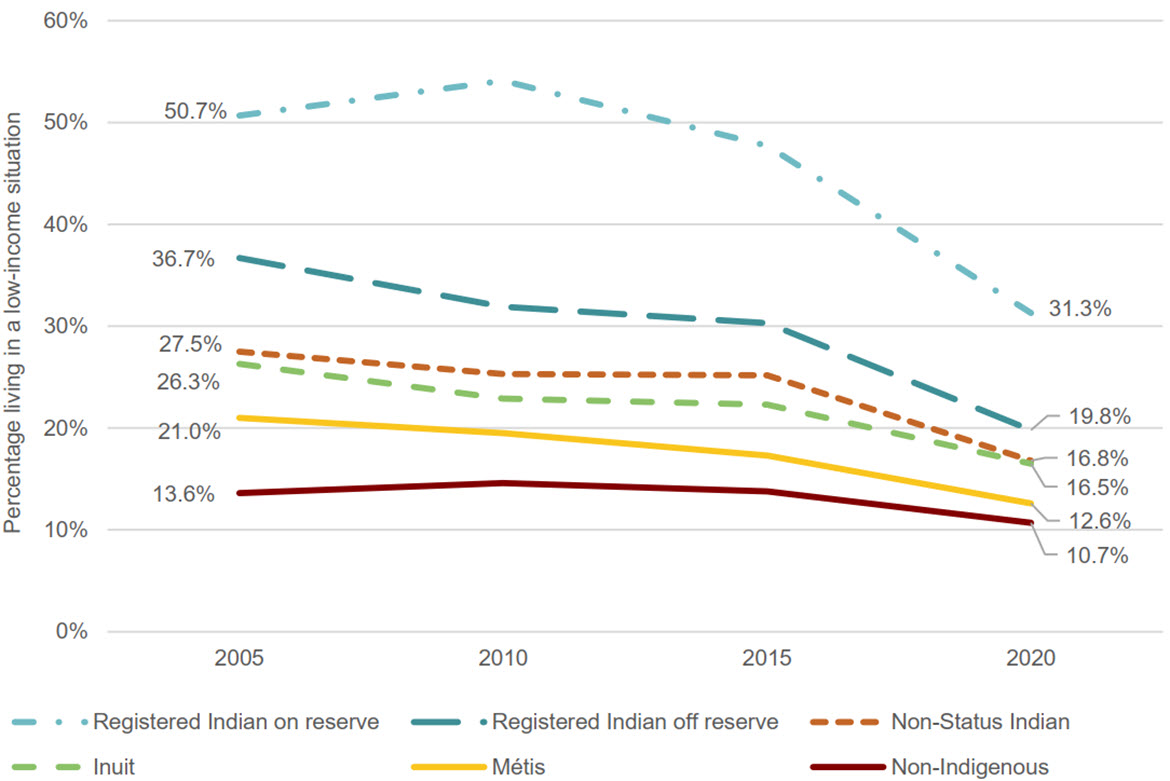

- Figure 10: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2005 to 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

- Figure 11: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2020, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, by region

- Figure 12: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2020, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, by region

- Figure 13: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2020, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, by Inuit region

- Figure 14: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, by gender, Canada

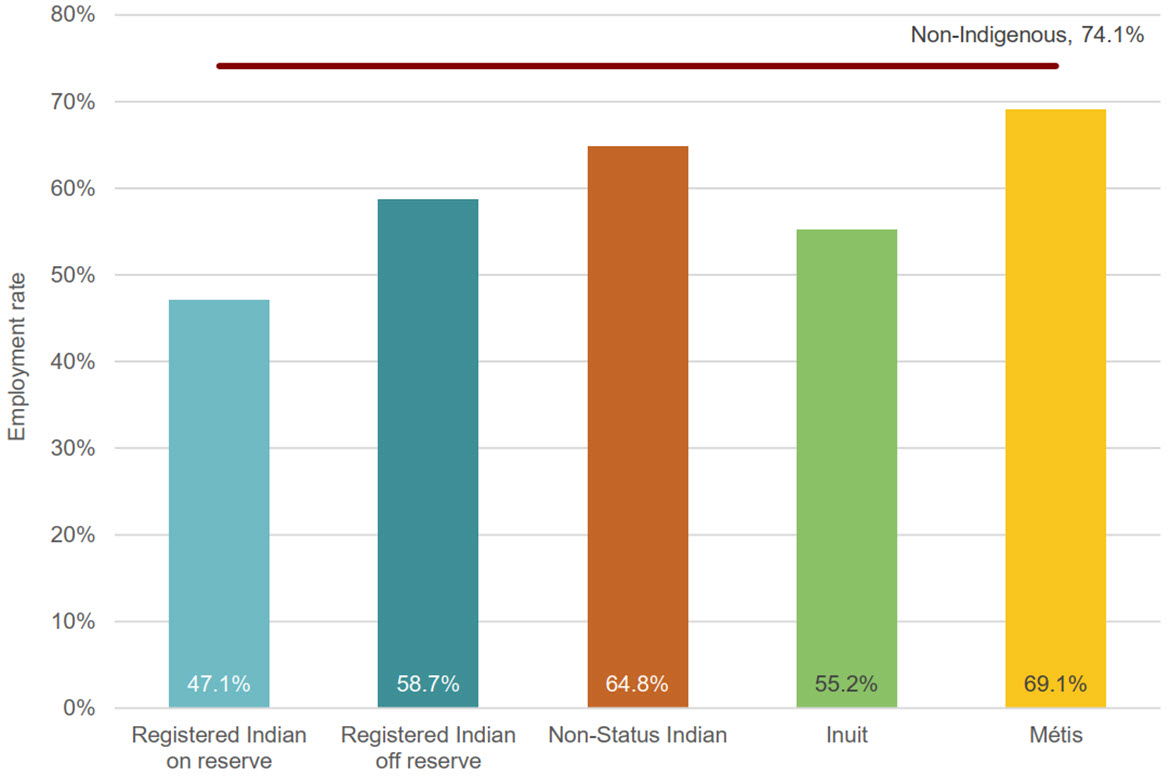

- Figure 15: Employment rate, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

- Figure 16: Employment rate, 2001 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

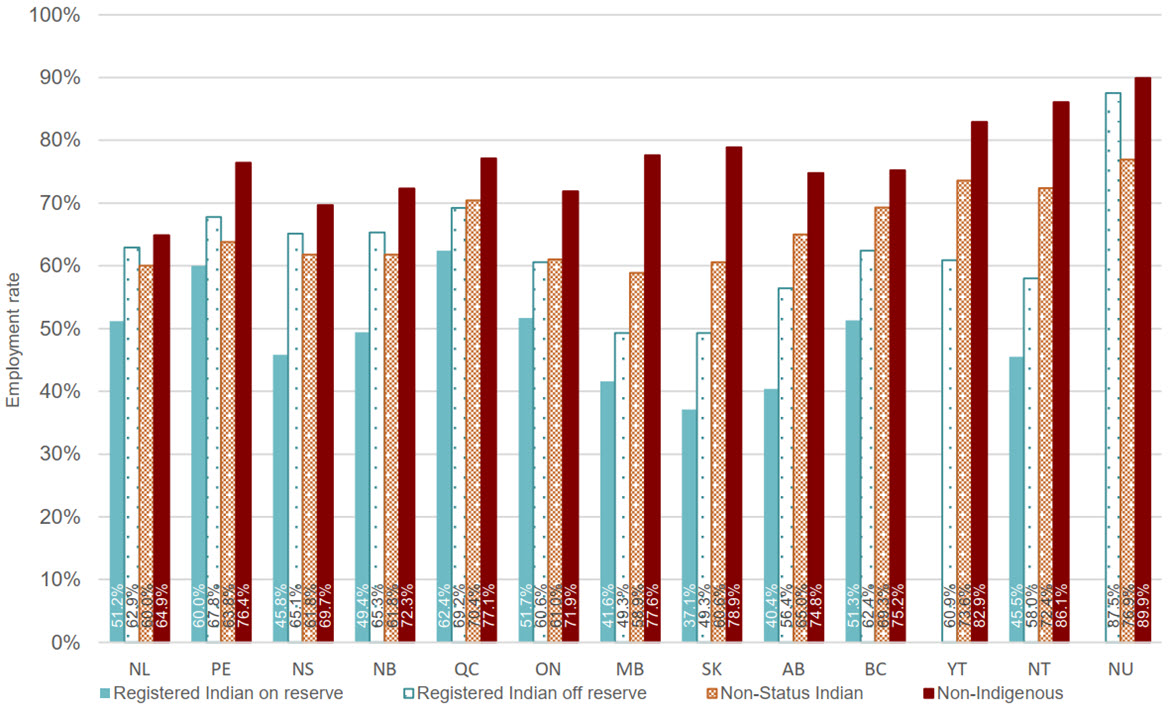

- Figure 17: Employment rate, 2021, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

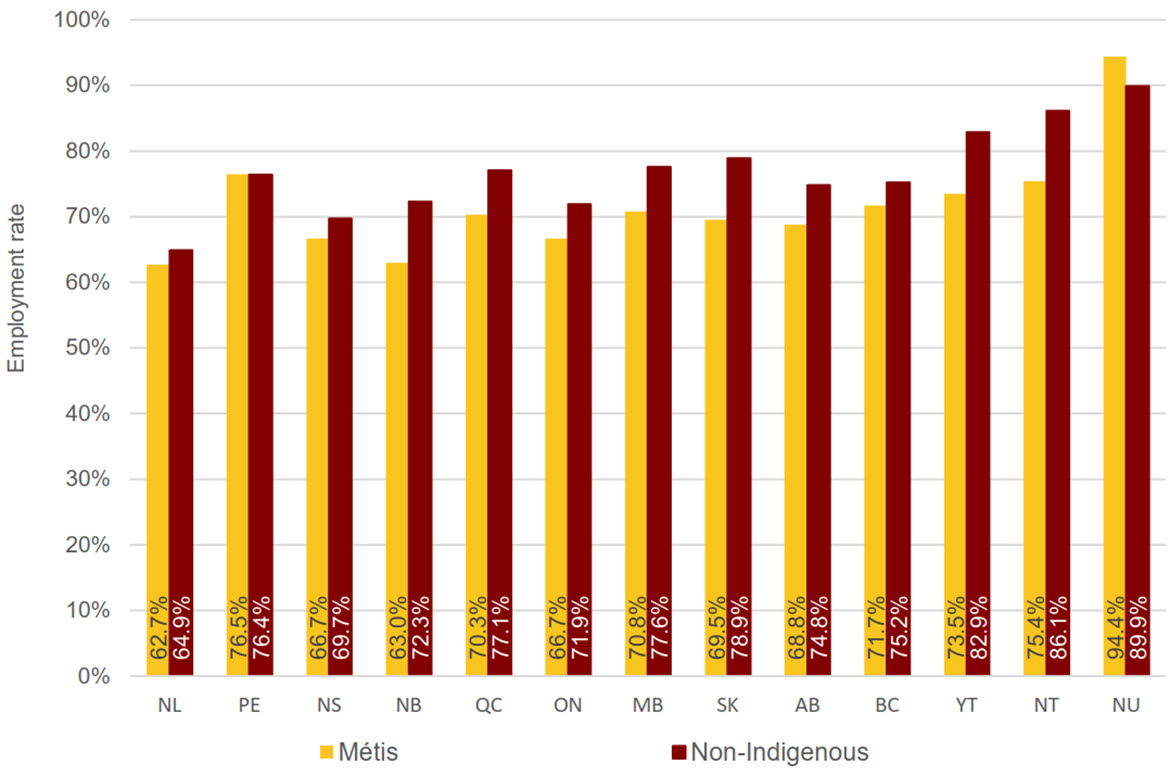

- Figure 18: Employment rate, 2021, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

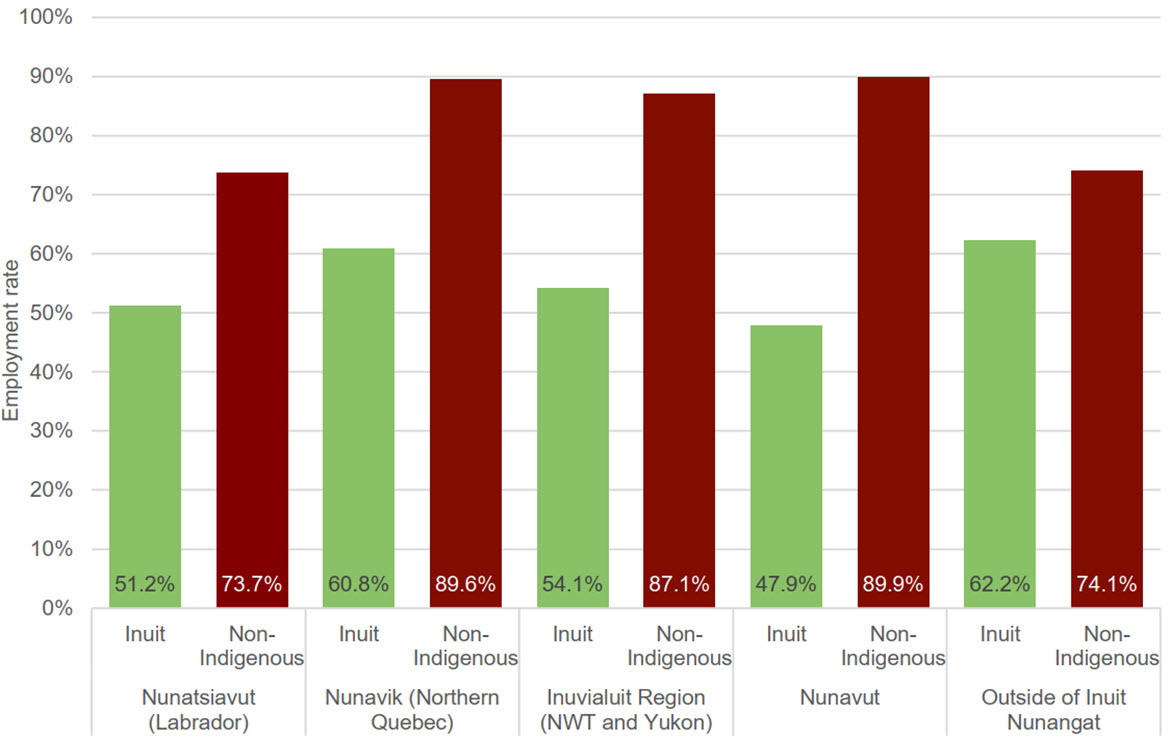

- Figure 19: Employment rate, 2021, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by Inuit region

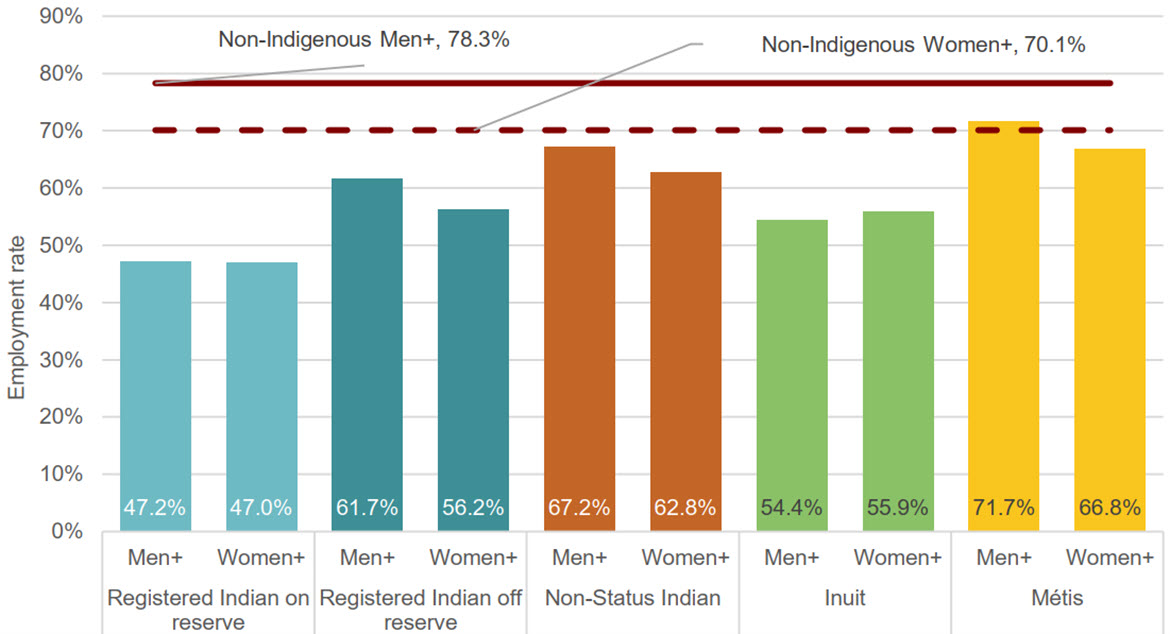

- Figure 20: Employment rate, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada

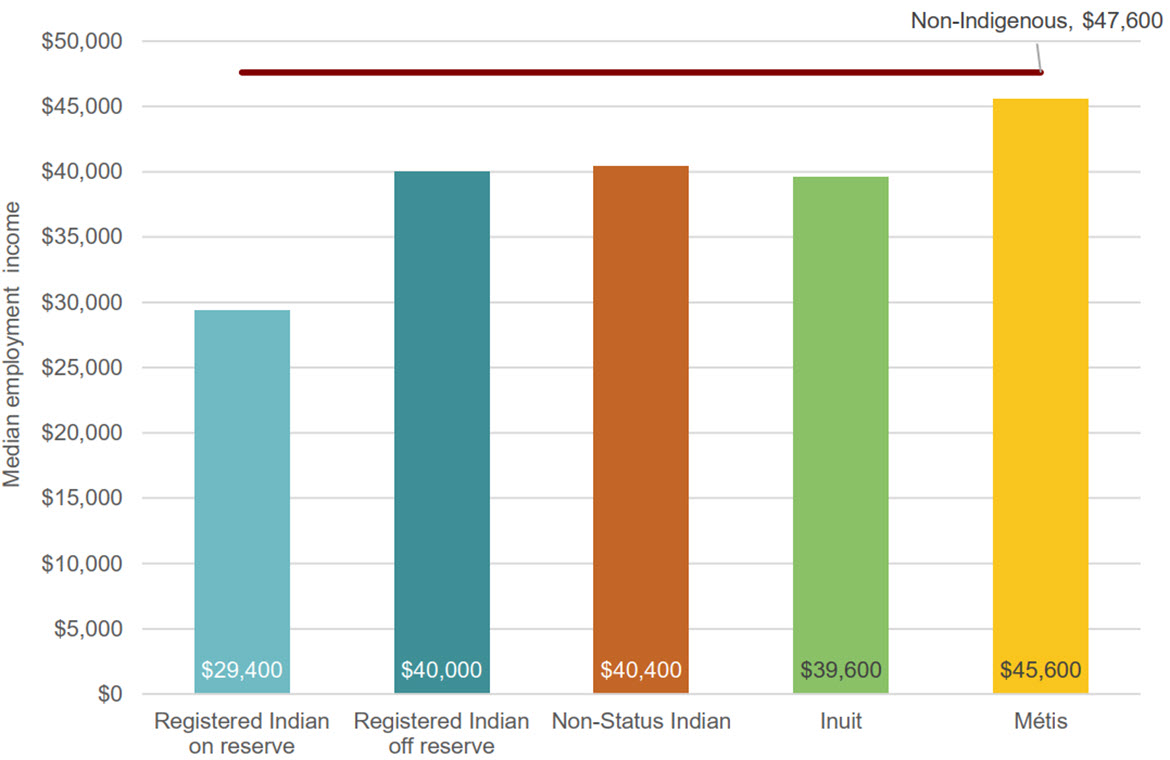

- Figure 21: Median employment income, 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

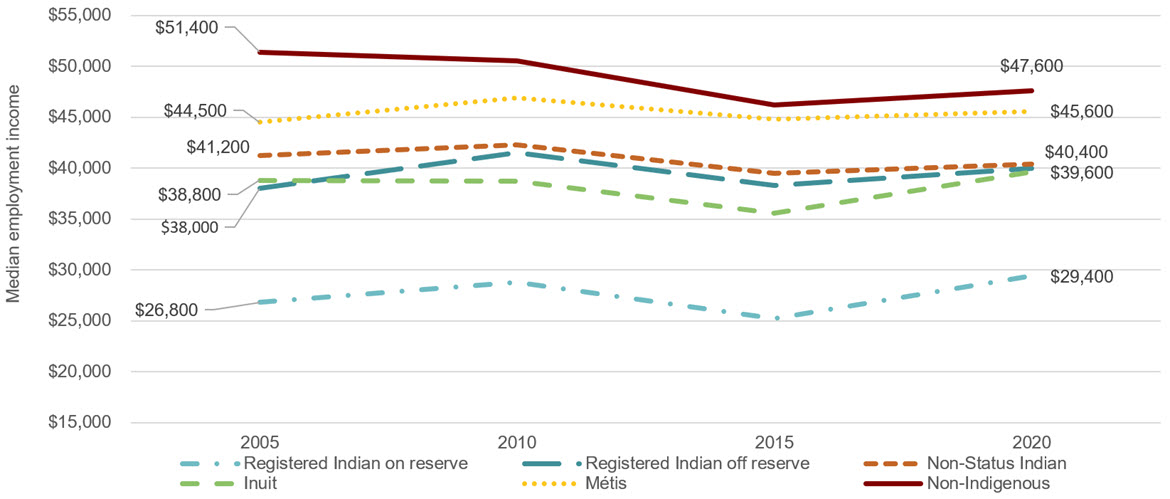

- Figure 22: Median employment income, 2005 to 2020 (adjusted), Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

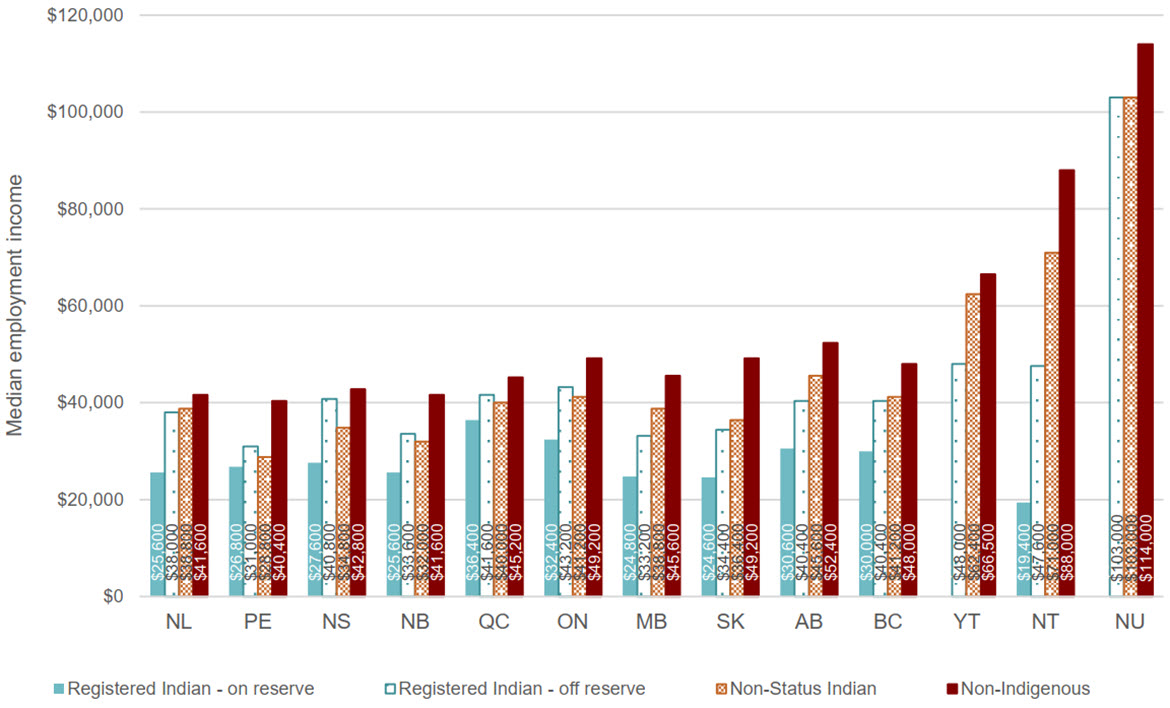

- Figure 23: Median employment income, 2020, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

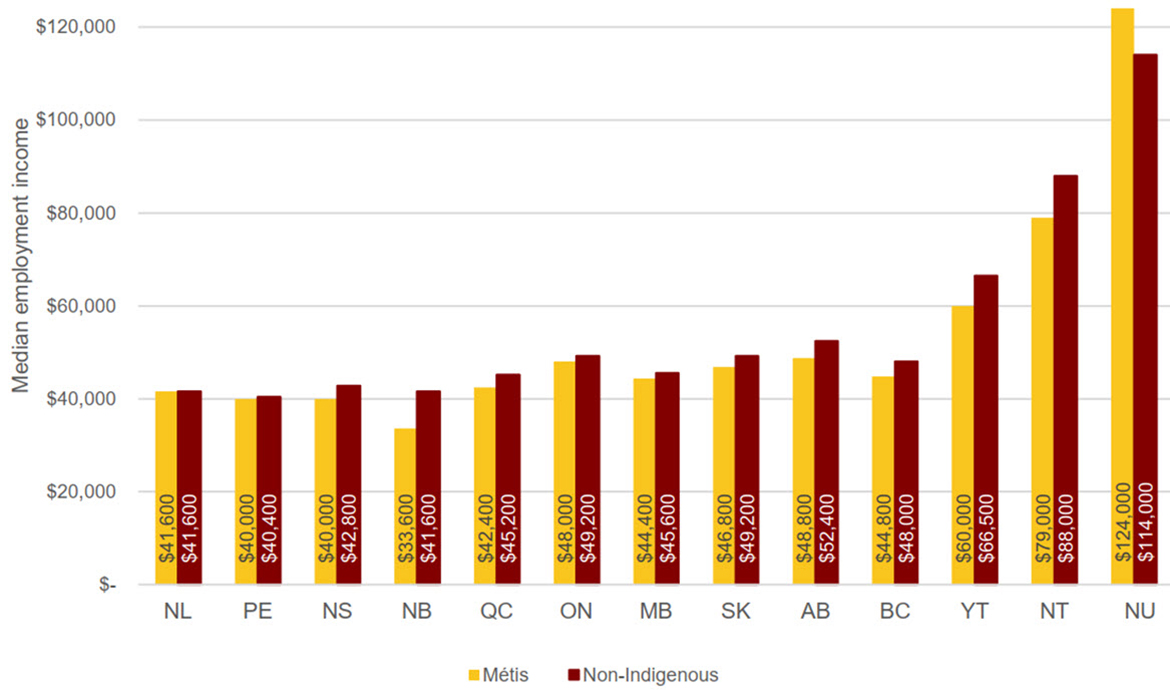

- Figure 24: Median employment income, 2020, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

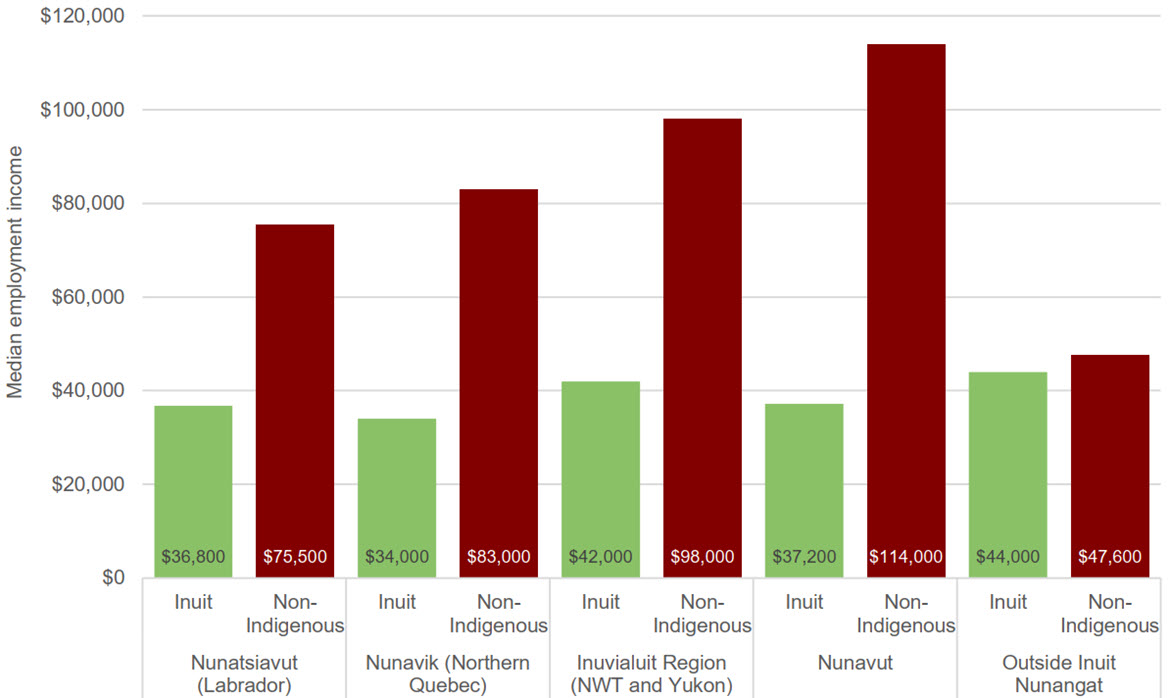

- Figure 25: Median employment income, 2020, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by Inuit region

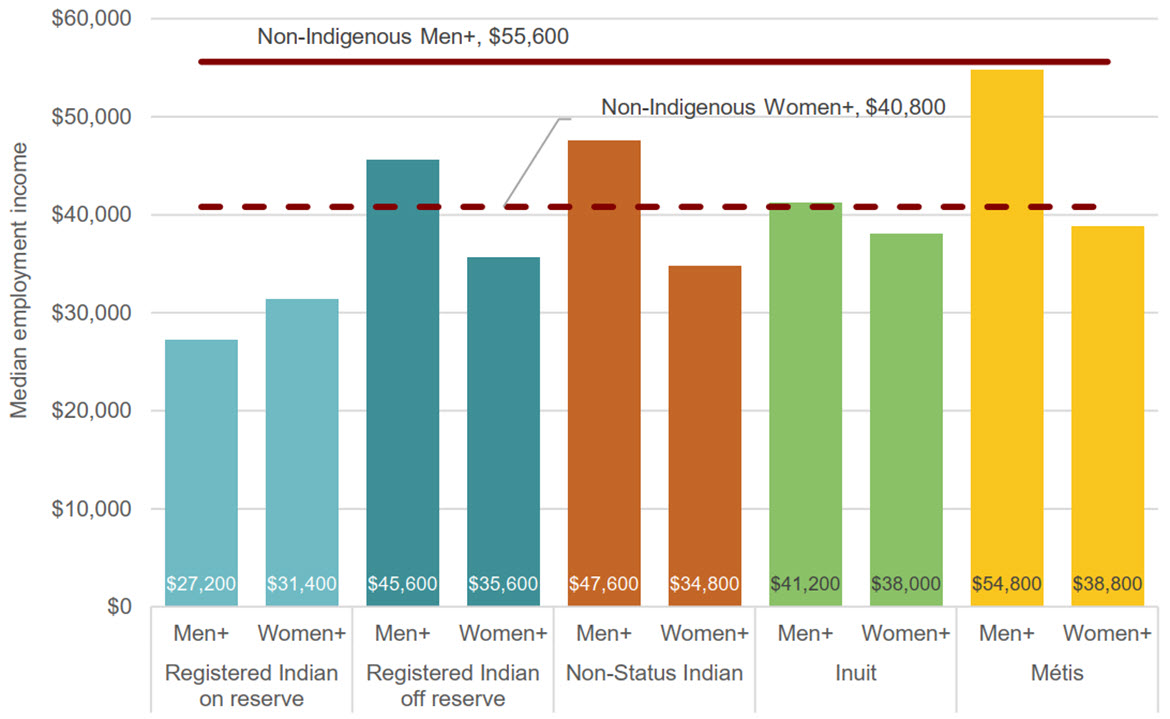

- Figure 26: Median employment income, 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada

- Figure 27: Percentage of people with at least a high school credential, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

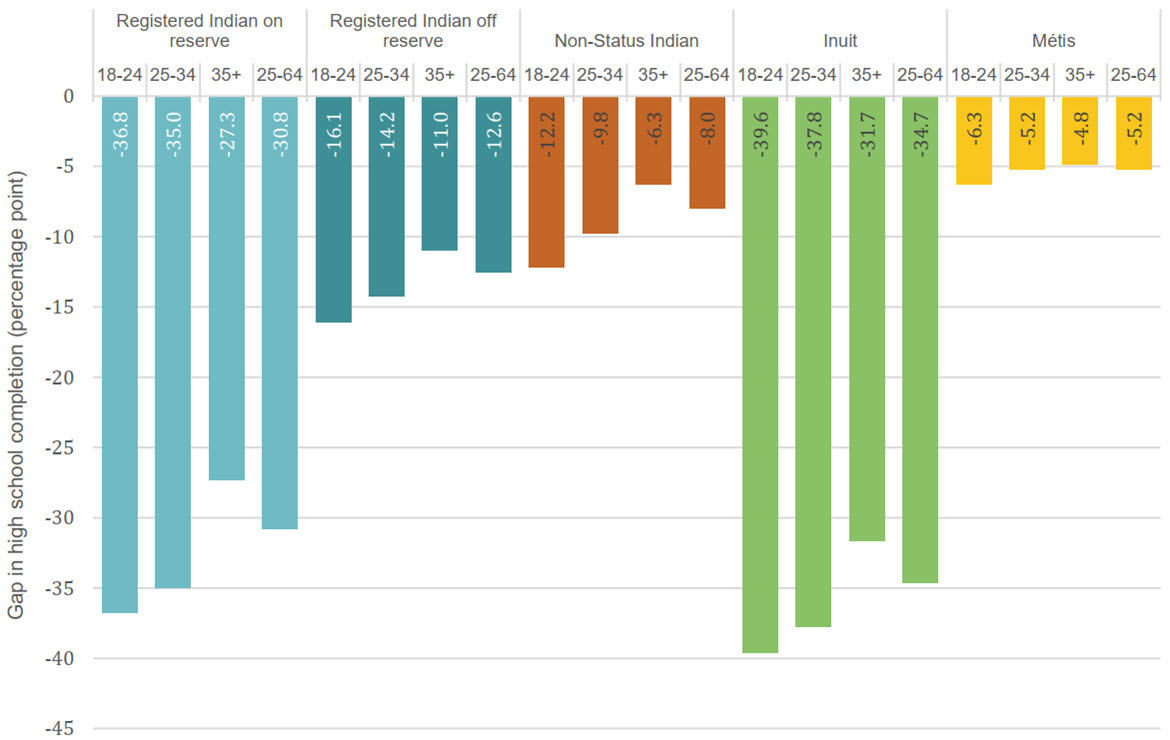

- Figure 28: Gap in high school completion (in percentage points) between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 18 to 24, 25 to 34, 35+ and 25 to 64, 2021, Canada

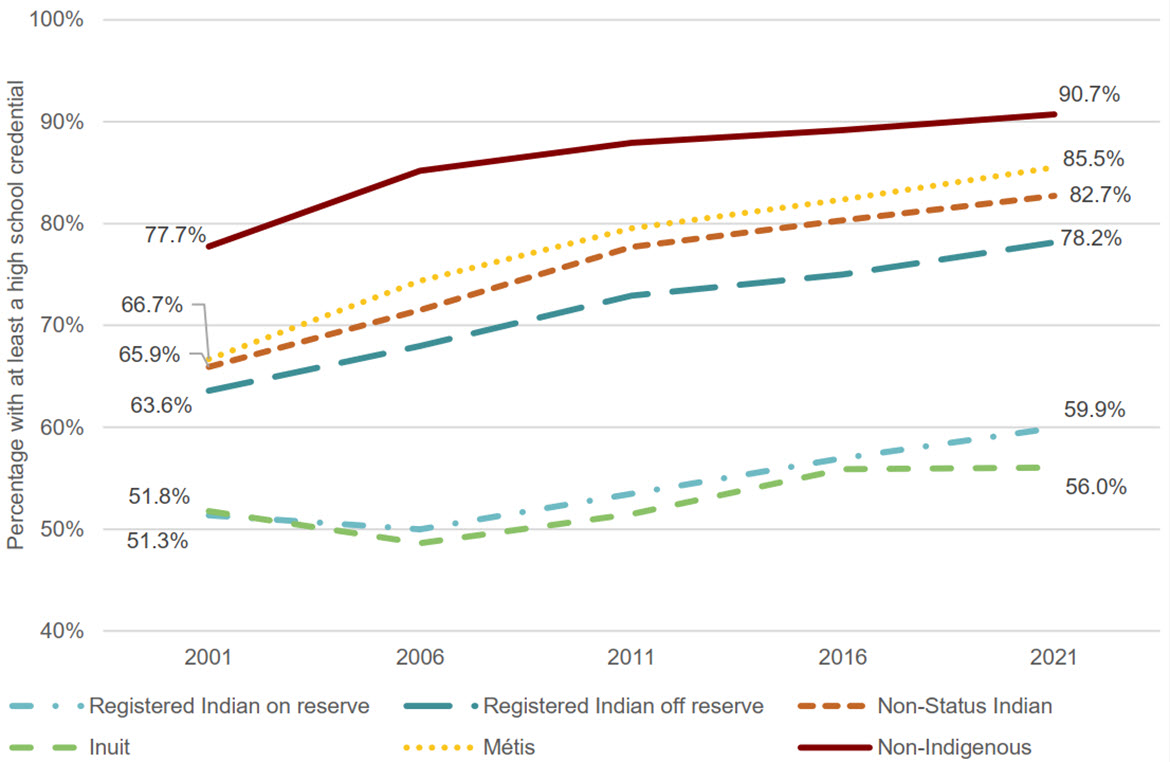

- Figure 29: Percentage of people with at least a high school credential, 2001 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

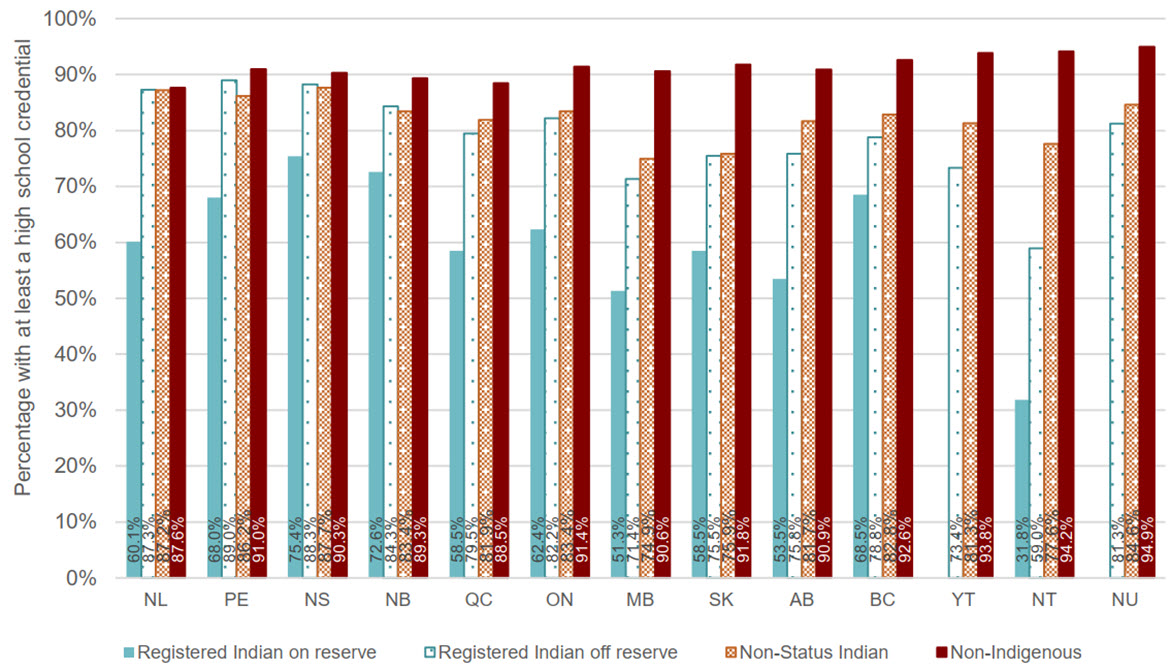

- Figure 30: Percentage of people with at least a high school credential, 2021, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

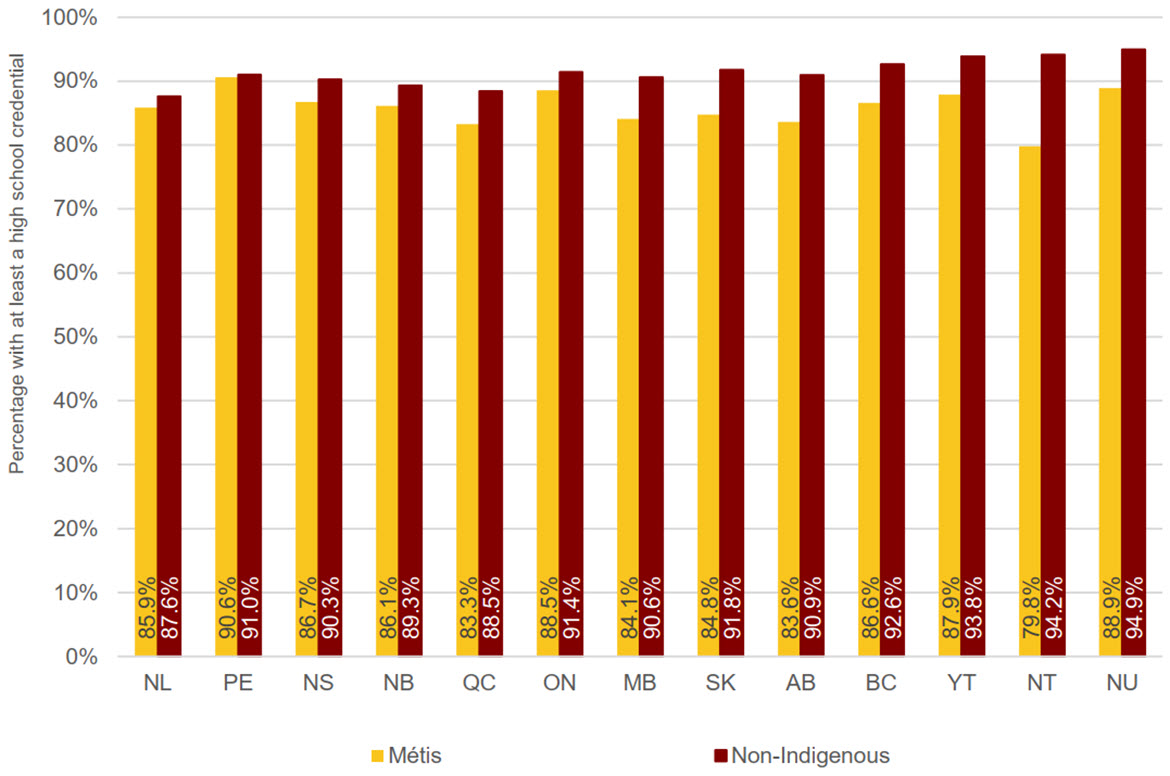

- Figure 31: Percentage of people with at least a high school credential, 2021, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

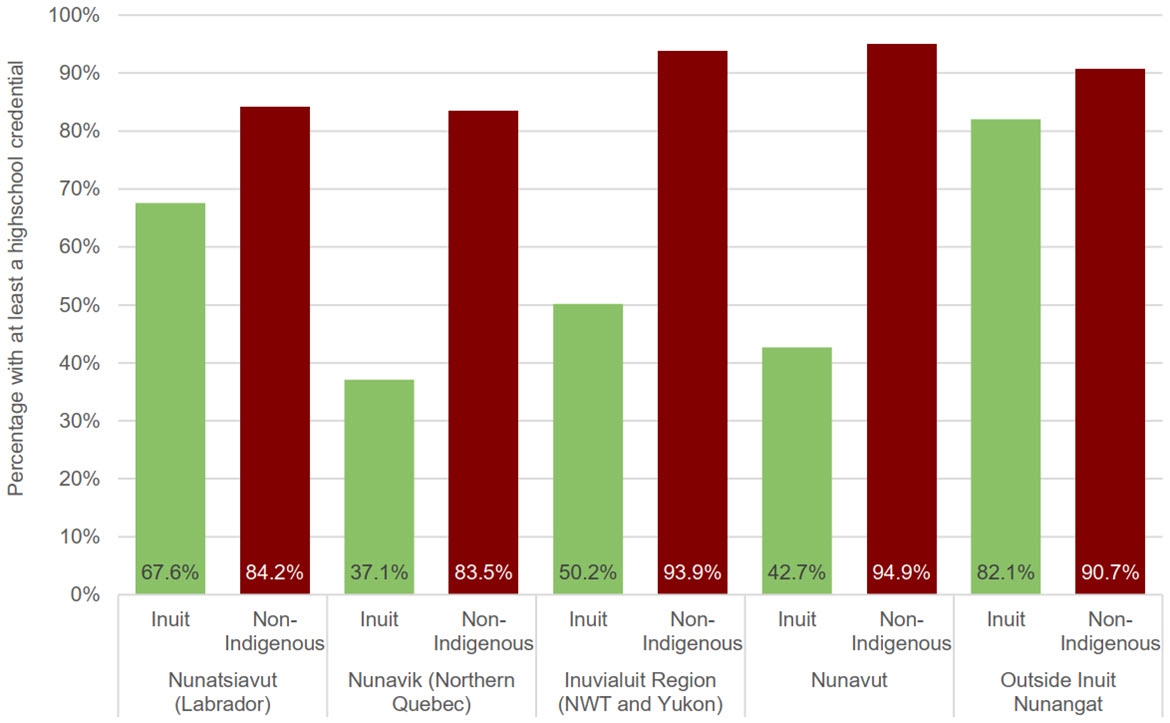

- Figure 32: Percentage with at least a high school credential, 2021, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by Inuit region

- Figure 33: Percentage of people with at least a high school credential, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada

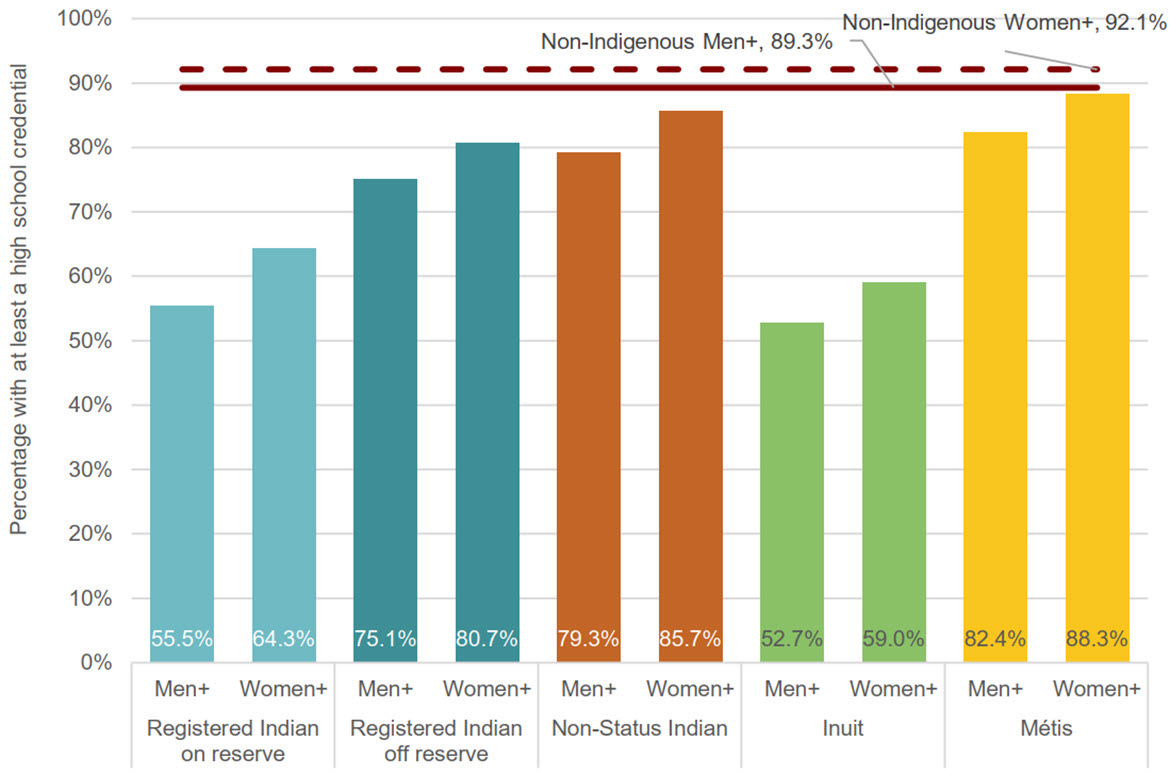

- Figure 34: Percentage of people with a university degree, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

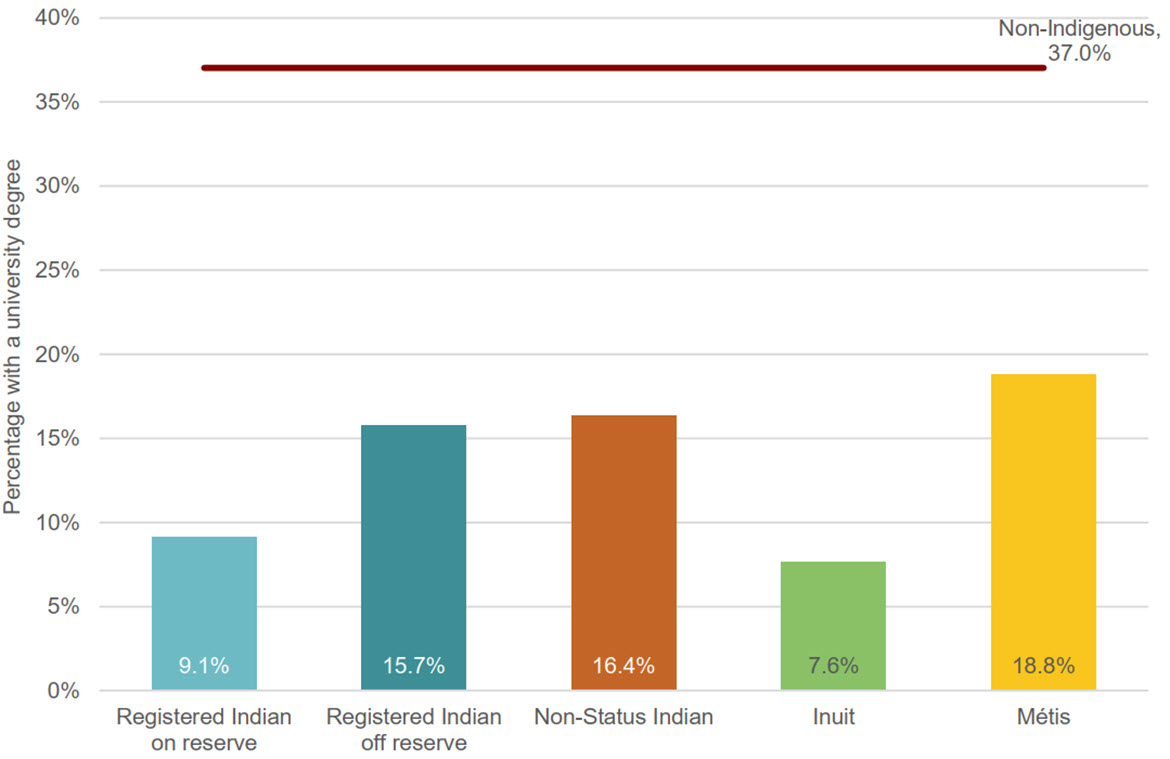

- Figure 35: Gap in university completion (in percentage points) between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 34 and 25 to 64, 2021, Canada

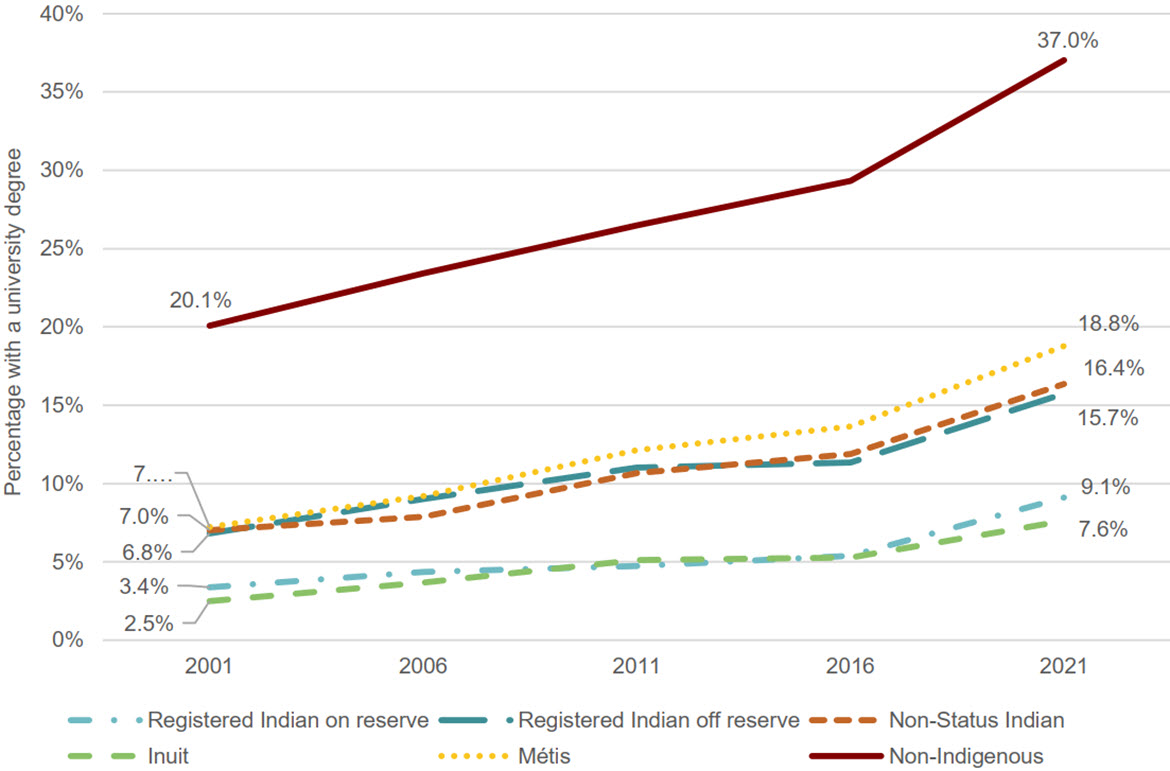

- Figure 36: Percentage of people with a university degree, 2001 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

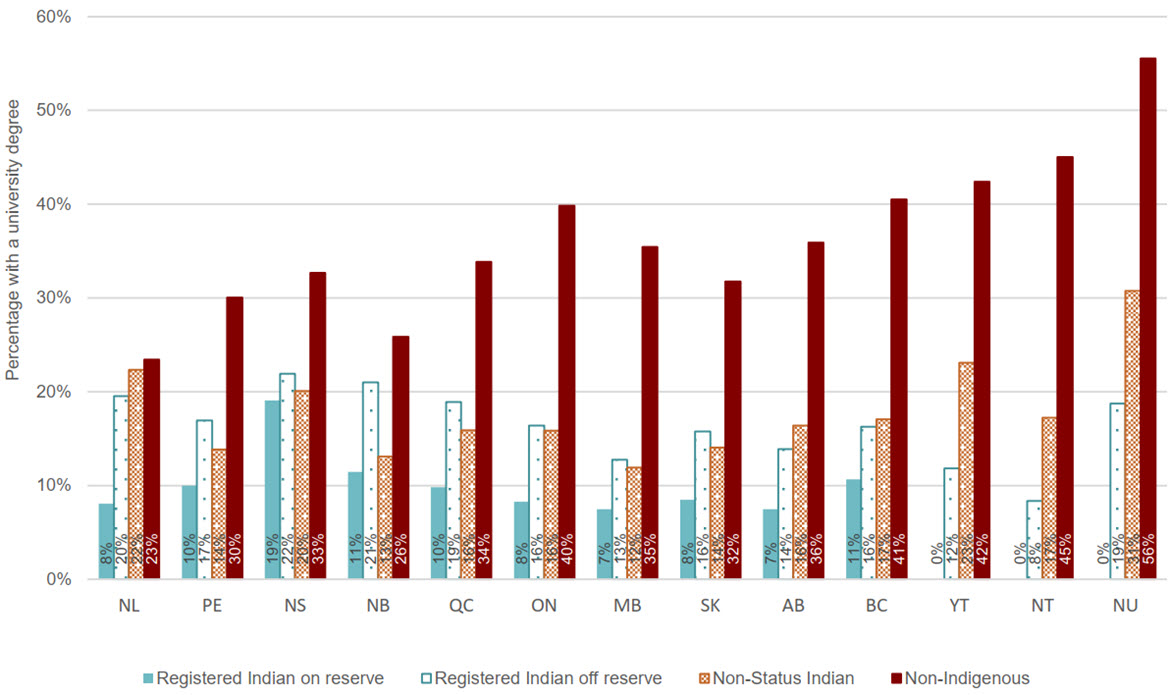

- Figure 37: Percentage of people with a university degree, 2021, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

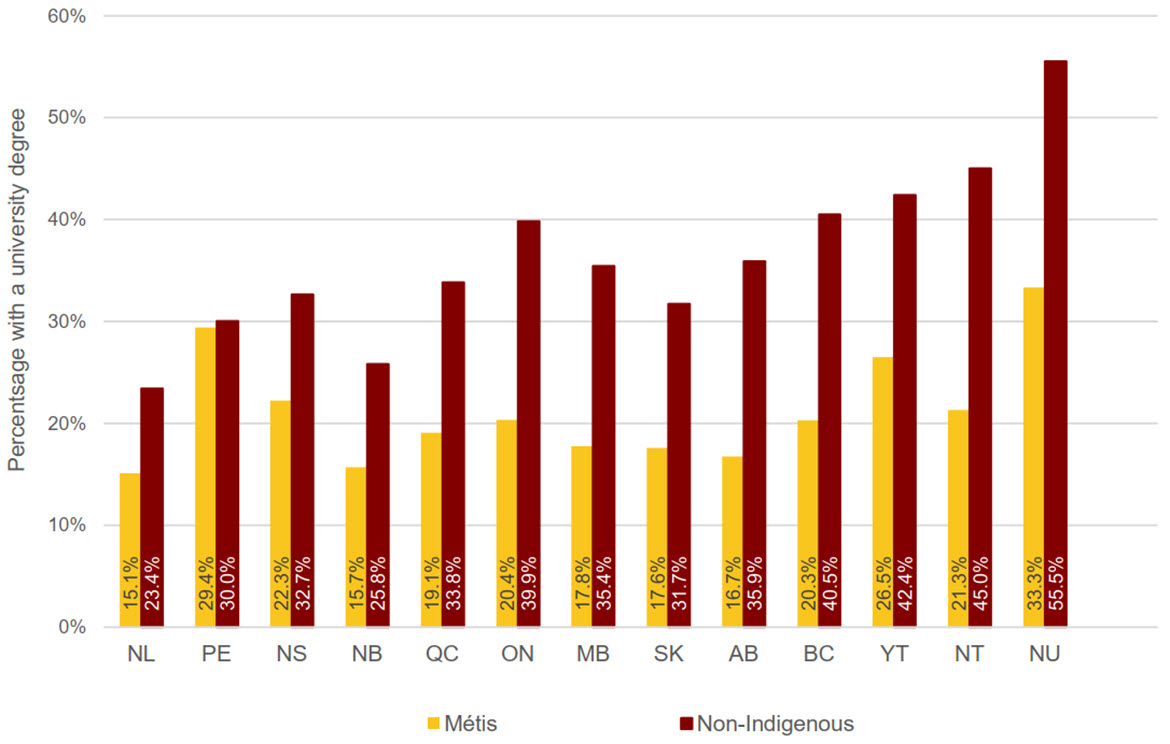

- Figure 38: Percentage of people with a university degree, 2021, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

- Figure 39: Percentage of people with a university degree, 2021, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

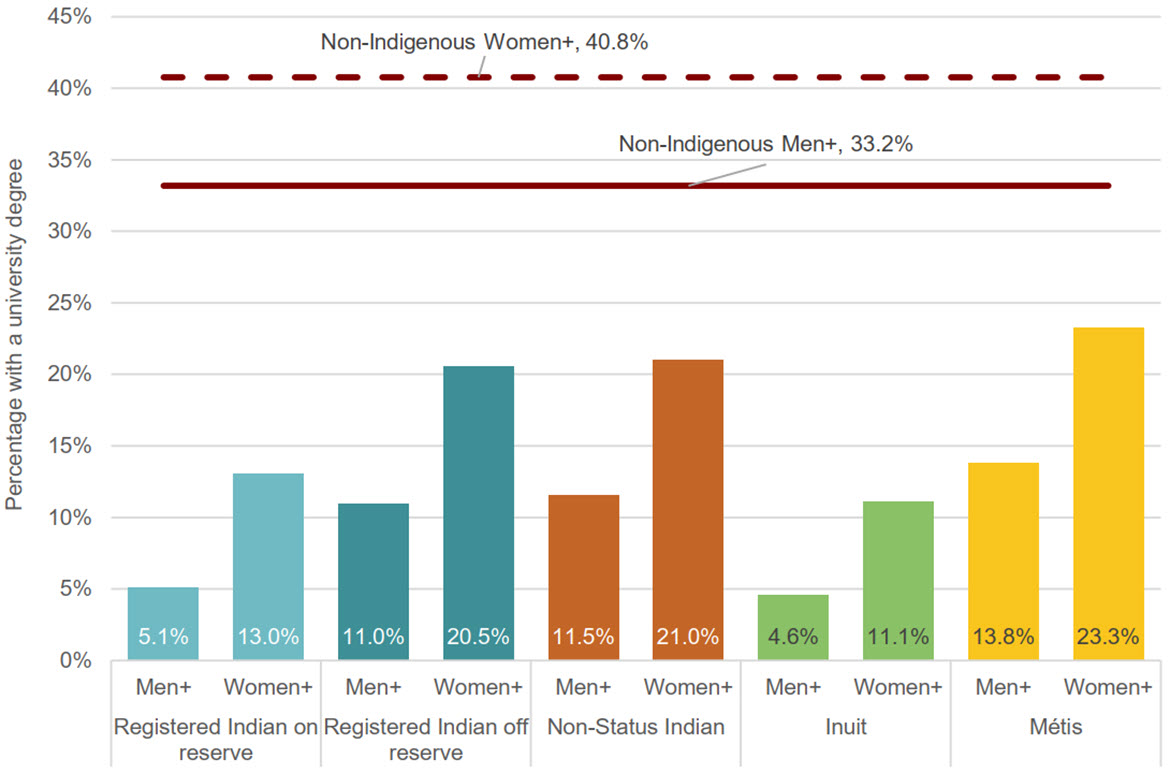

- Figure 40: Percentage of people with a university degree, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada

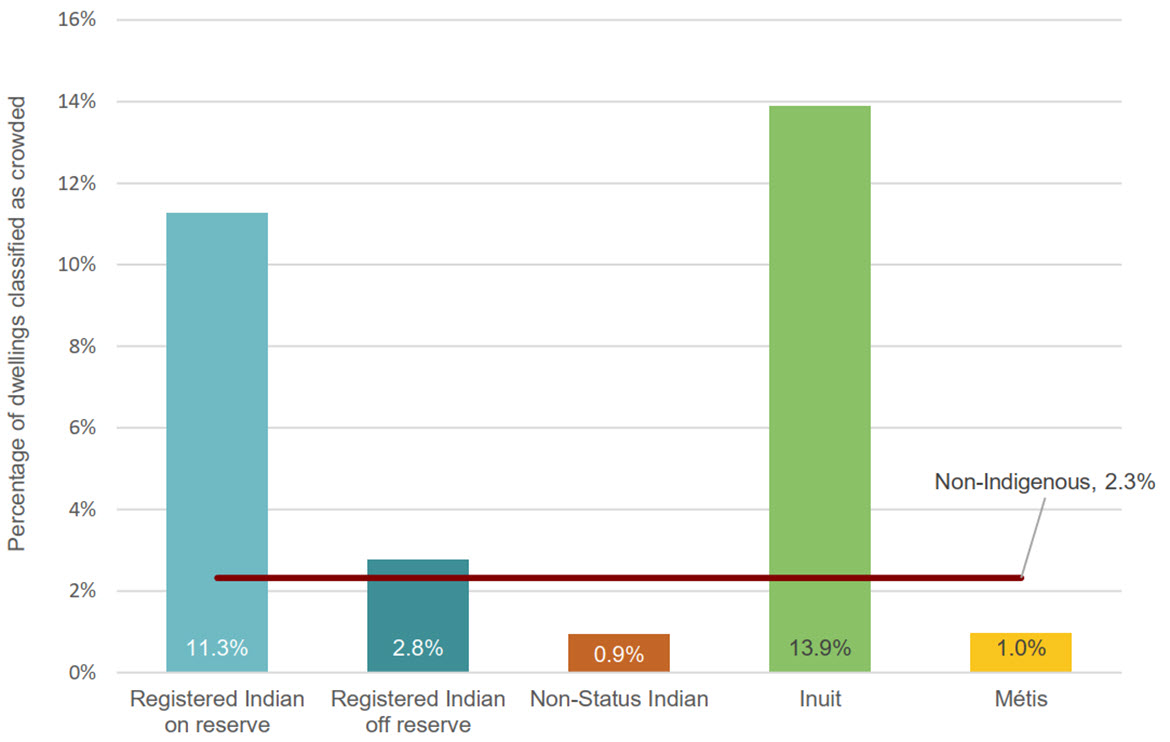

- Figure 41: Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

- Figure 42: Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded, 2001 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

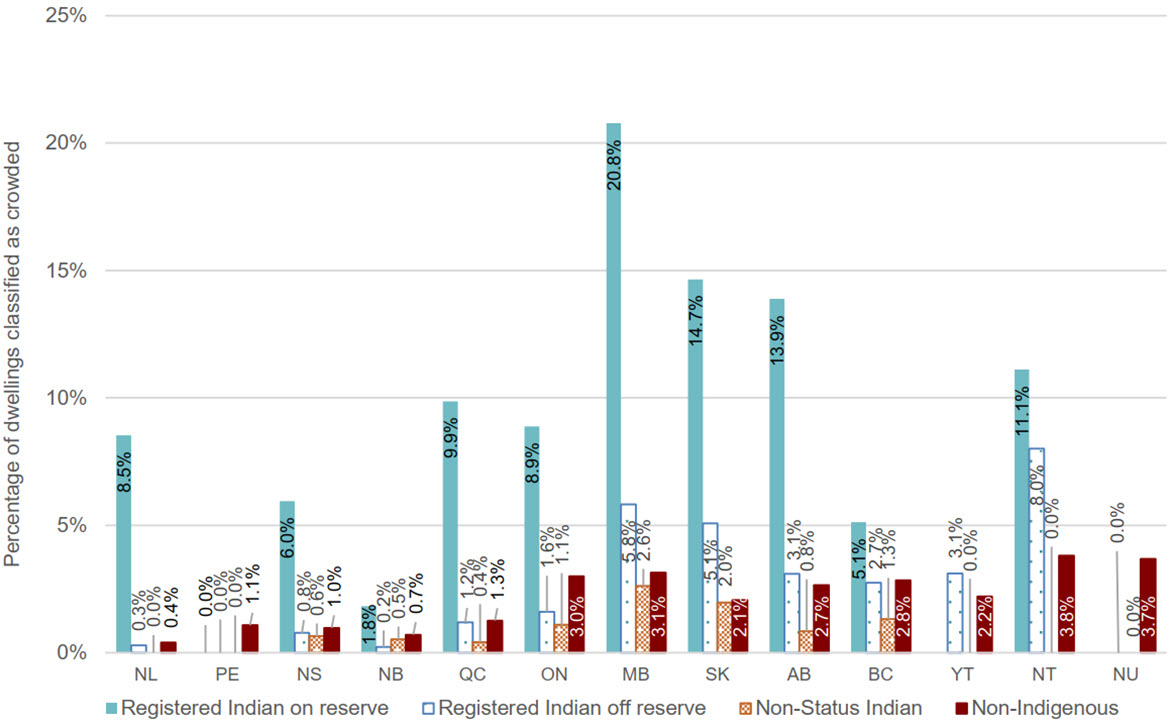

- Figure 43: Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded, 2021, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, by region

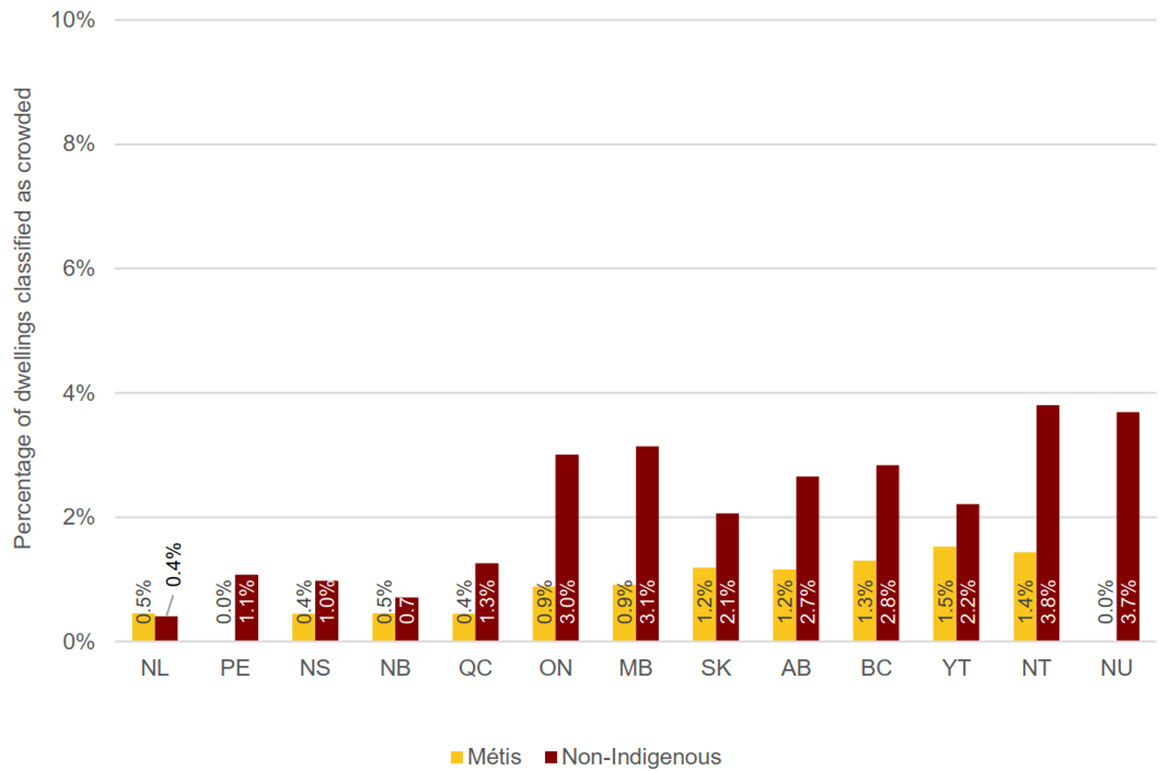

- Figure 44: Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded, 2021, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, by region

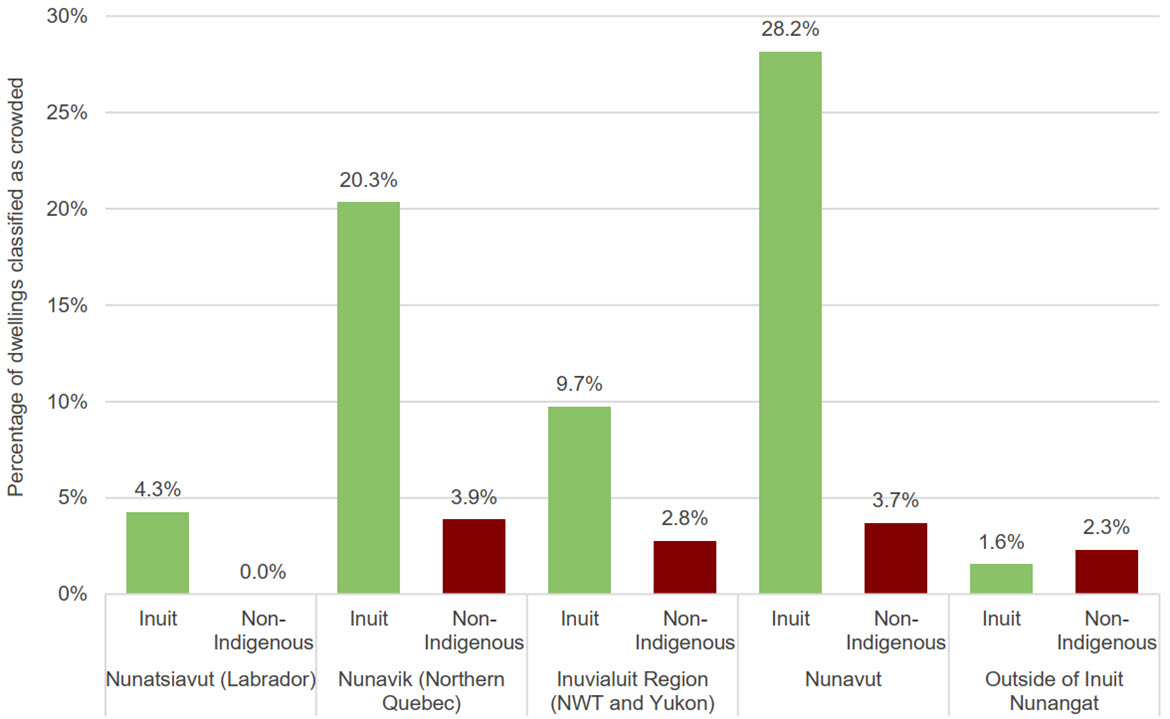

- Figure 45: Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded, 2021, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, by region

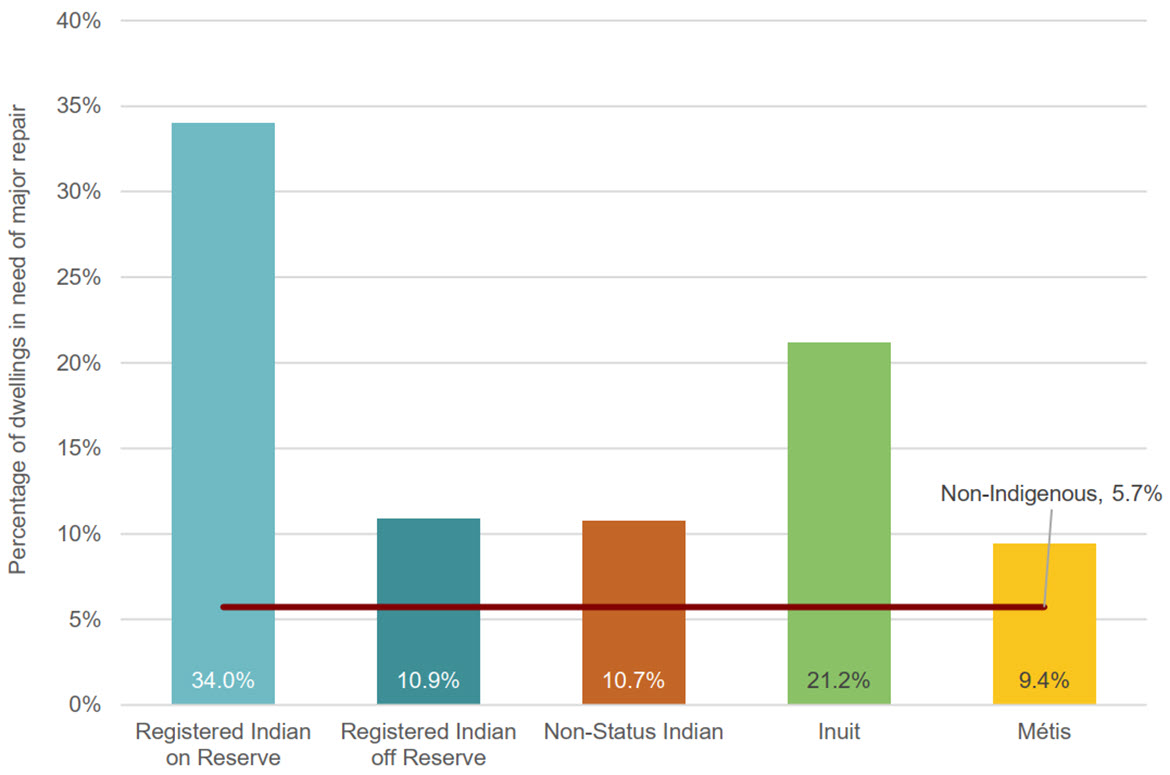

- Figure 46: Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

- Figure 47: Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair, 2001 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

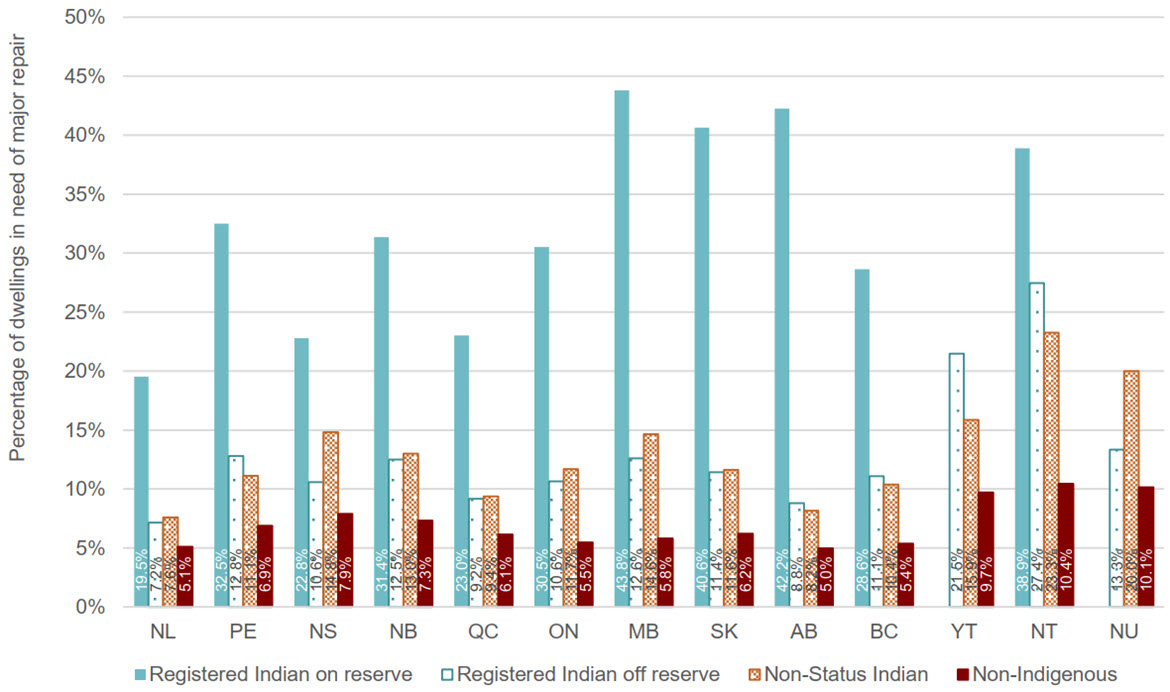

- Figure 48: Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair, 2021, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, by region

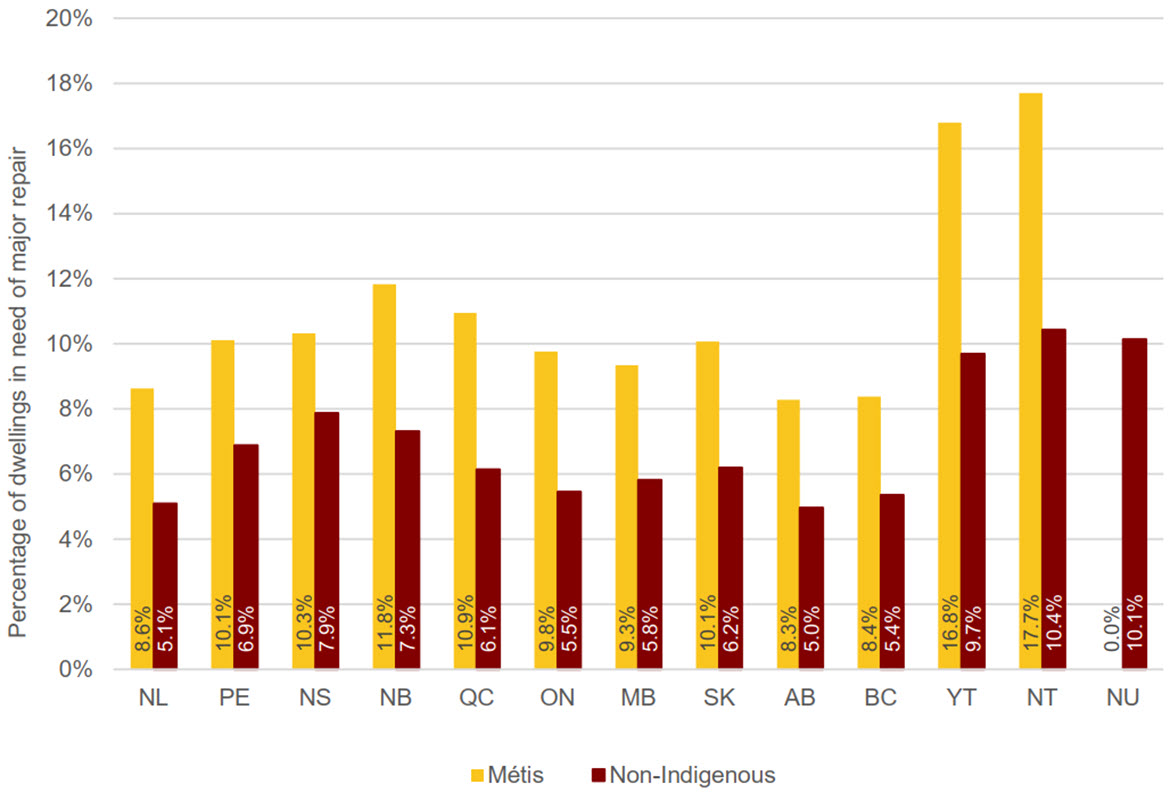

- Figure 49: Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair, 2021, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, by region

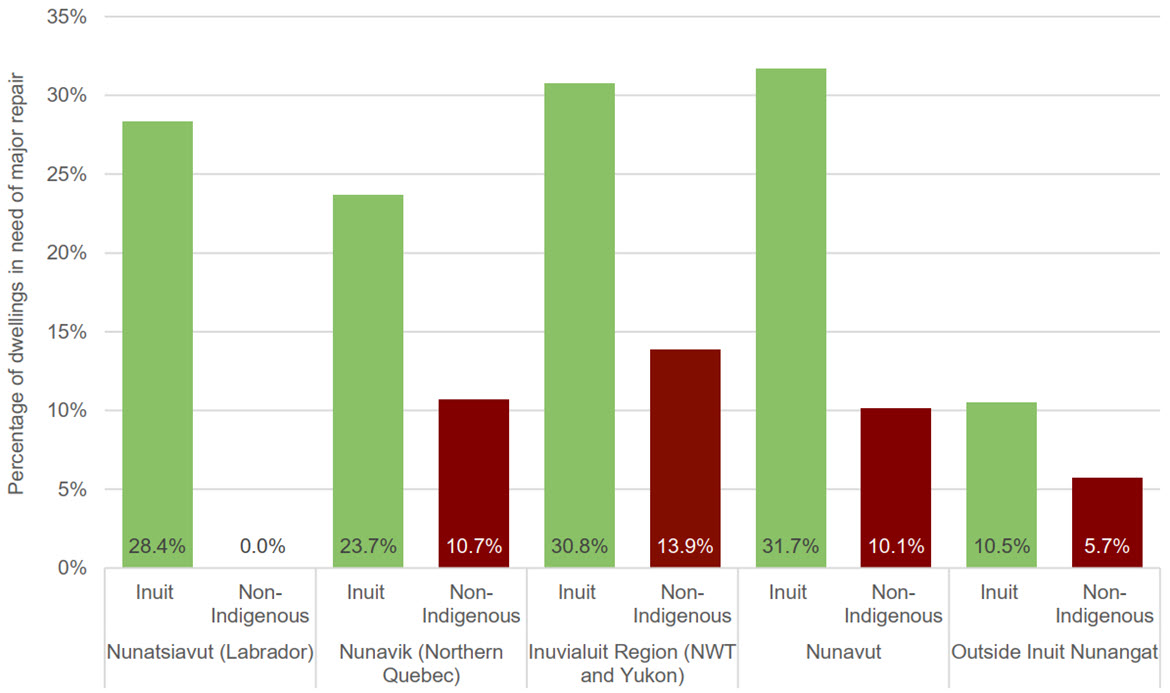

- Figure 50: Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair, 2021, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, by Inuit region

- Figure 51: Percentage of Indigenous and non-Indigenous children comprising the total population of children aged 0 to 17 in foster care, 2021, Canada

- Figure 52: Percentage of children aged 0 to 17 in foster care, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

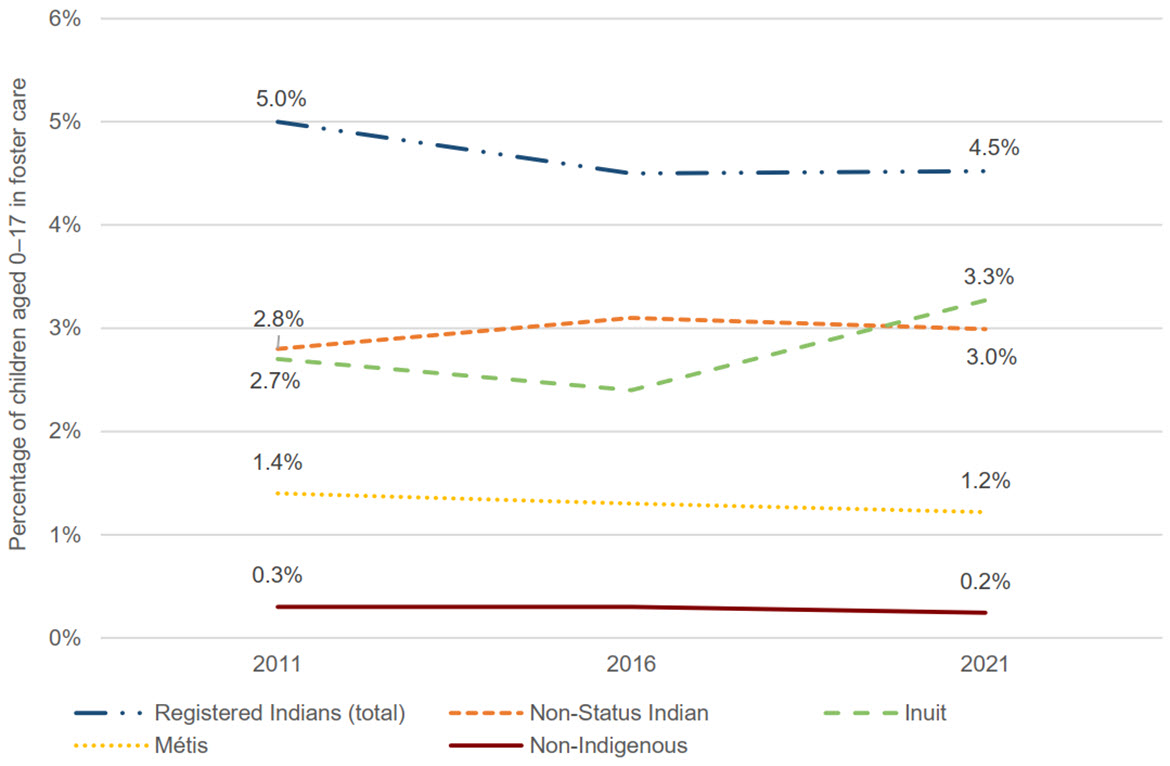

- Figure 53: Percentage of children aged 0 to 17 in foster care, 2011 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

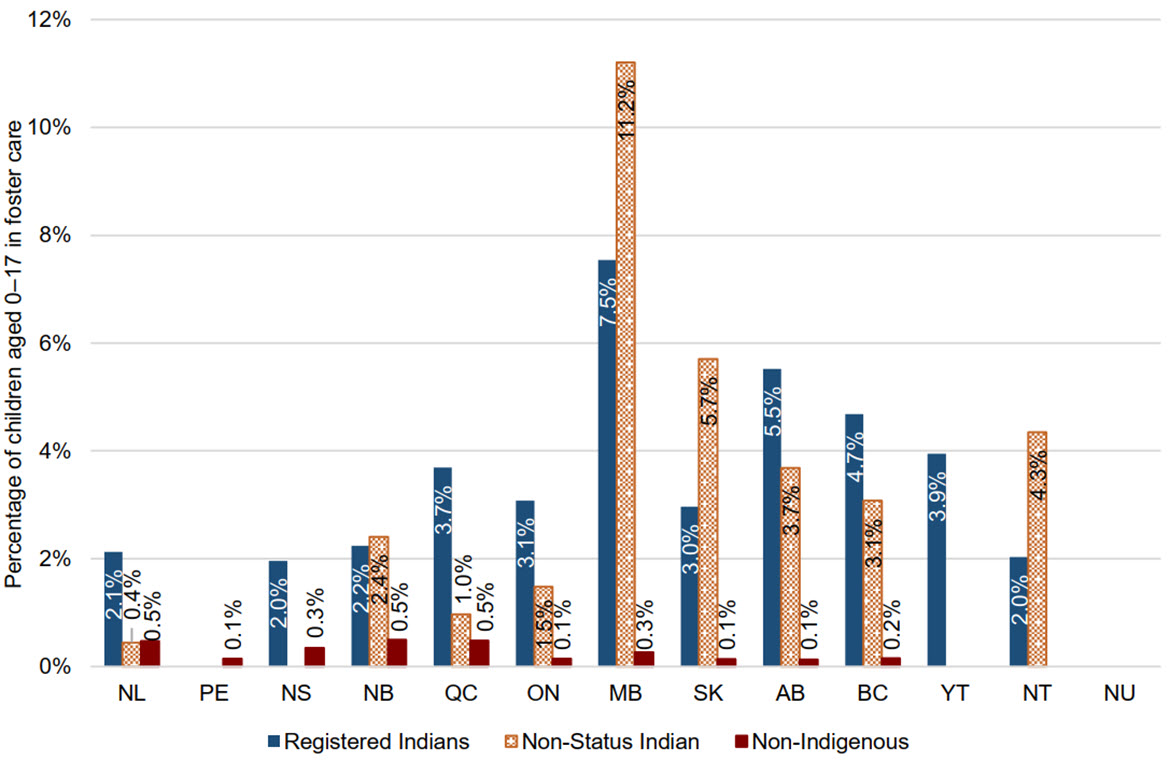

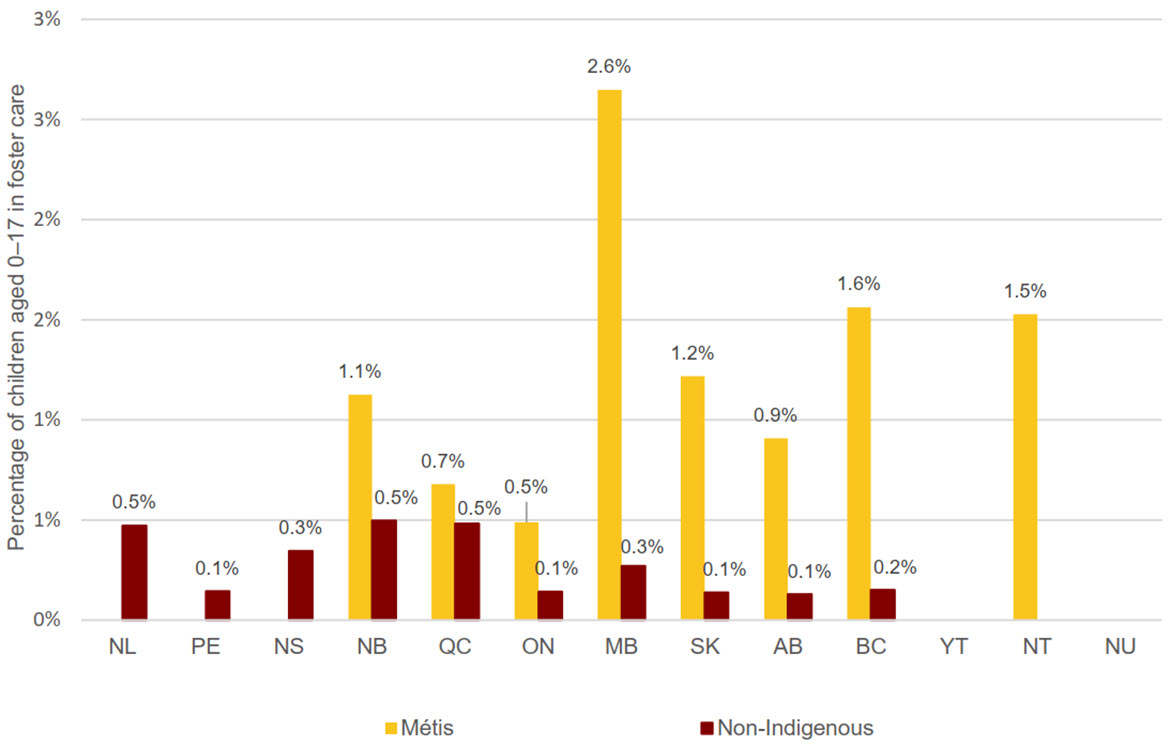

- Figure 54: Percentage of children aged 0 to 17 in foster care, 2021, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, by region

- Figure 55: Percentage of children aged 0 to 17 in foster care, 2021, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, by region

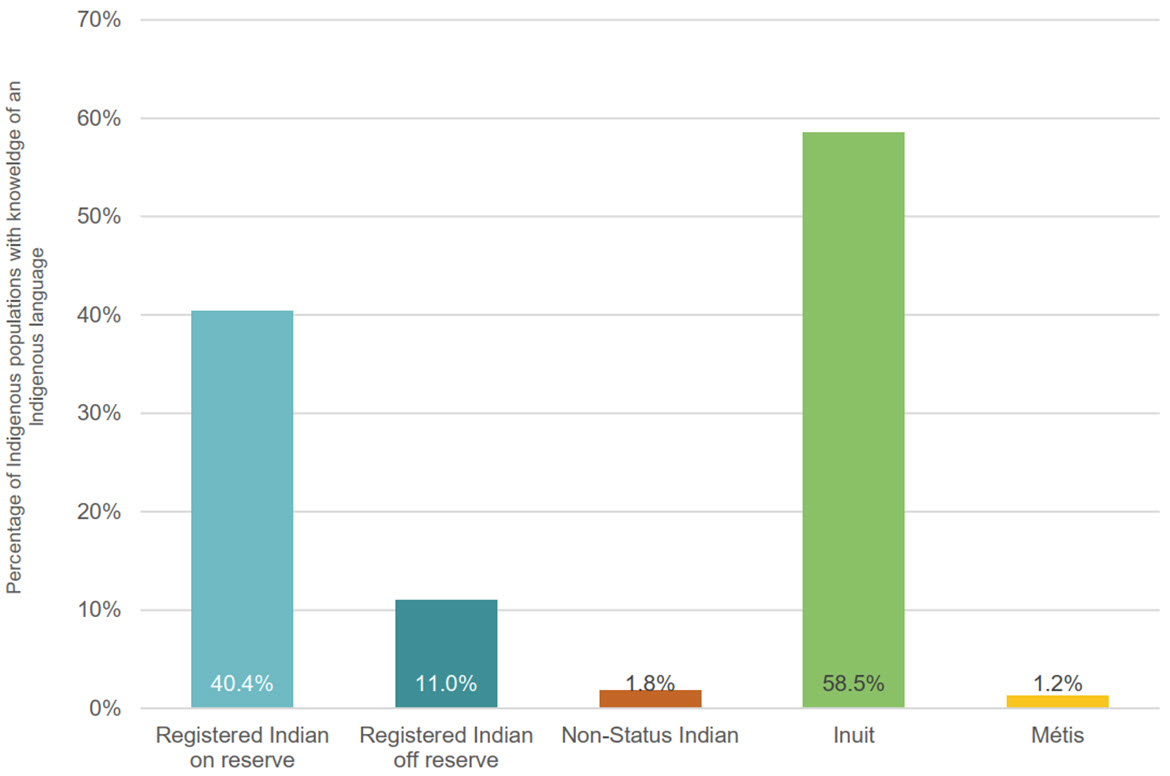

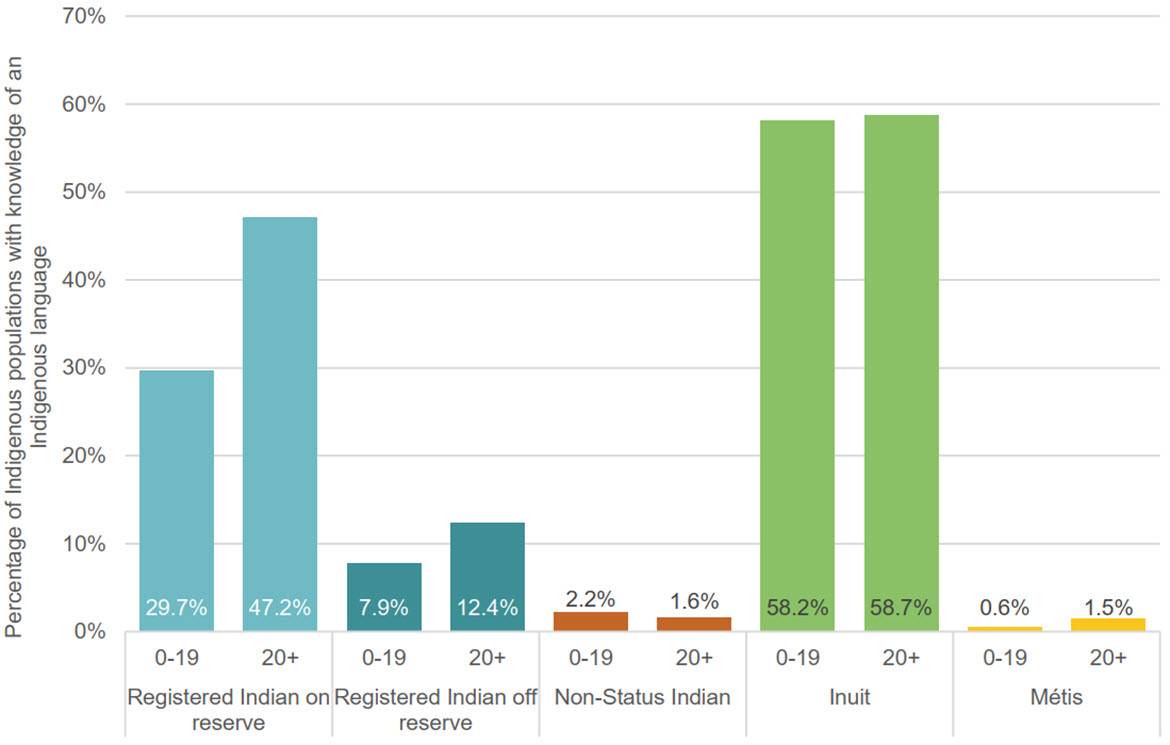

- Figure 56: Percentage of Indigenous populations with knowledge of an Indigenous language, 2021, Canada

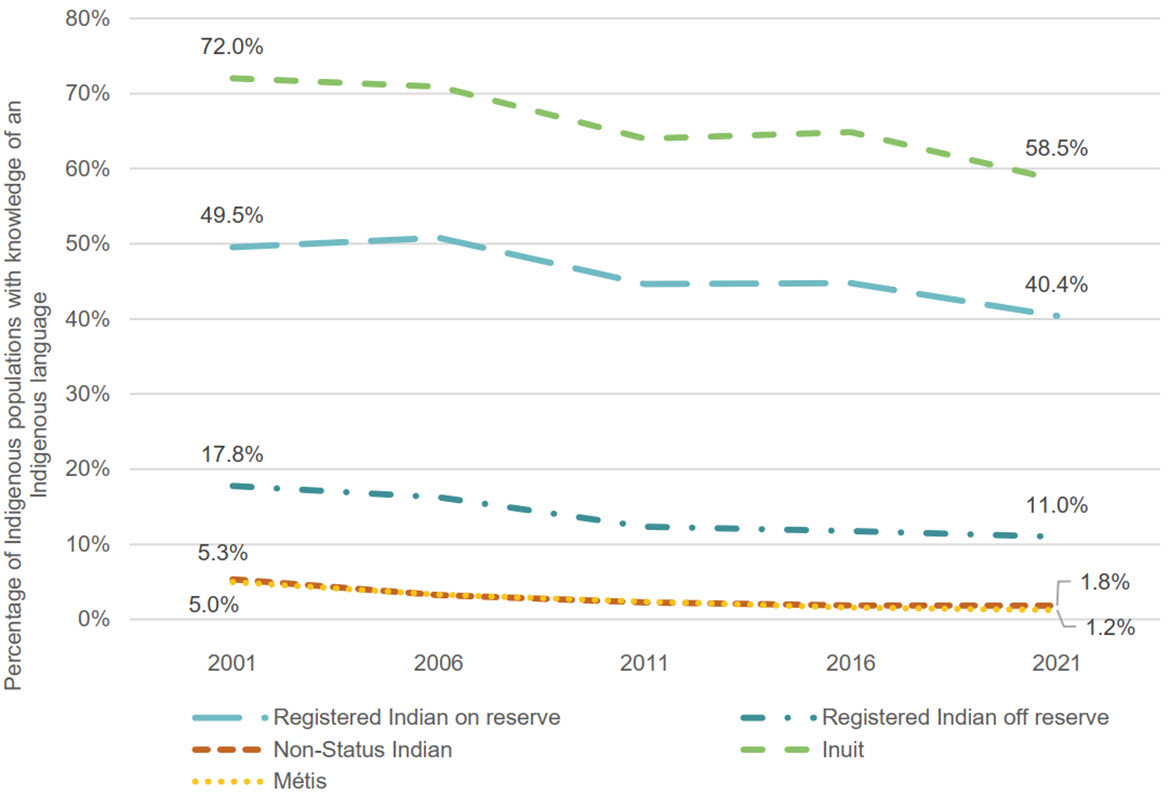

- Figure 57: Percentage of Indigenous populations with knowledge of an Indigenous language, 2001 to 2021, Canada

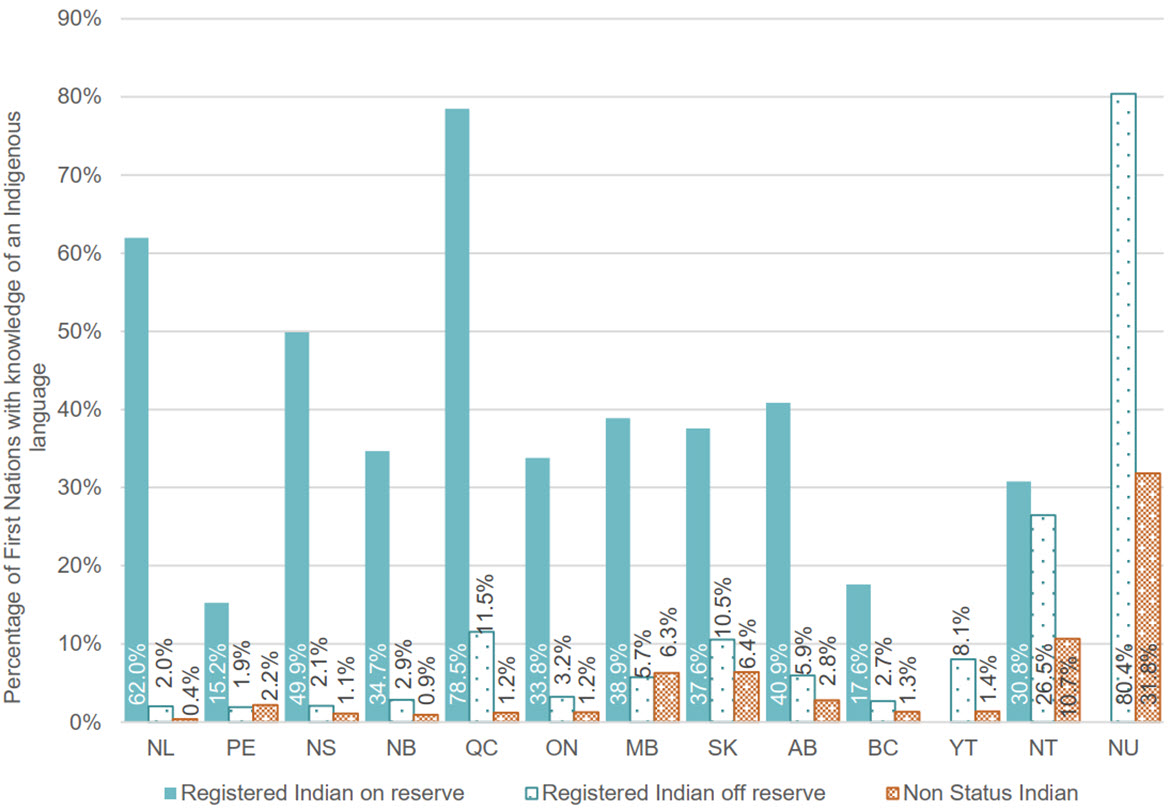

- Figure 58: Percentage of First Nations with knowledge of an Indigenous language, 2021, by region

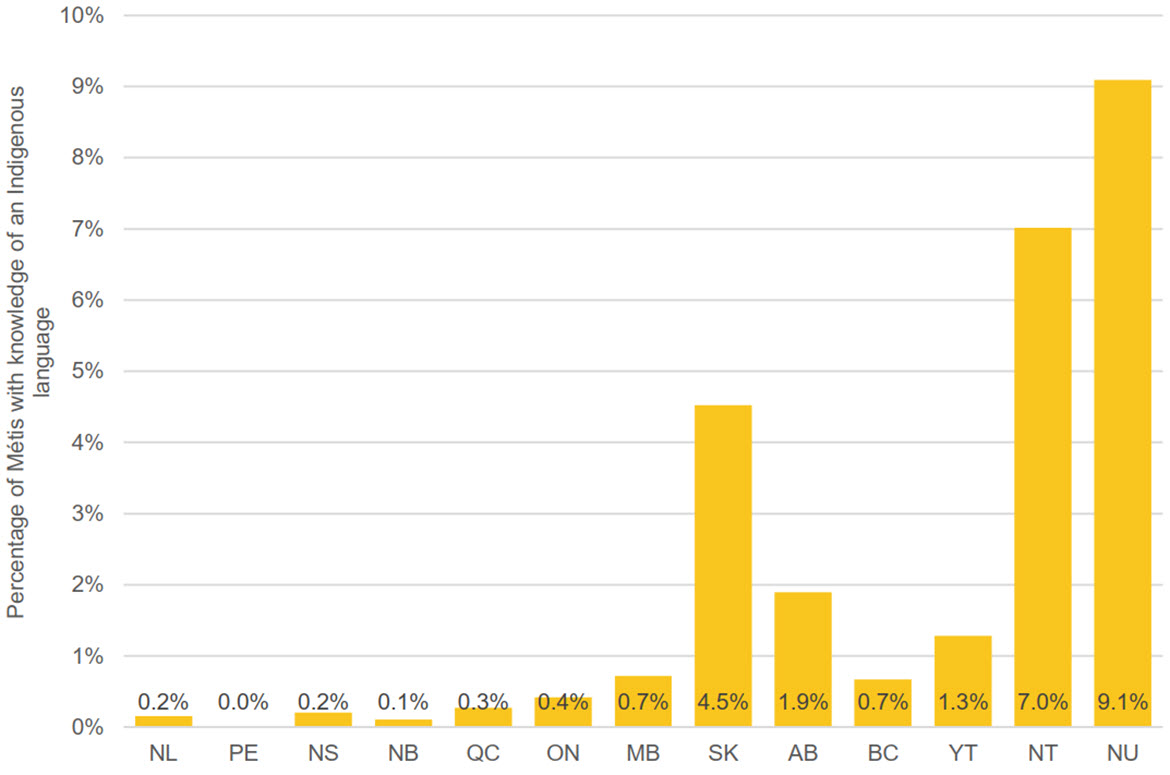

- Figure 59: Percentage of Métis with knowledge of an Indigenous language, 2021, by region

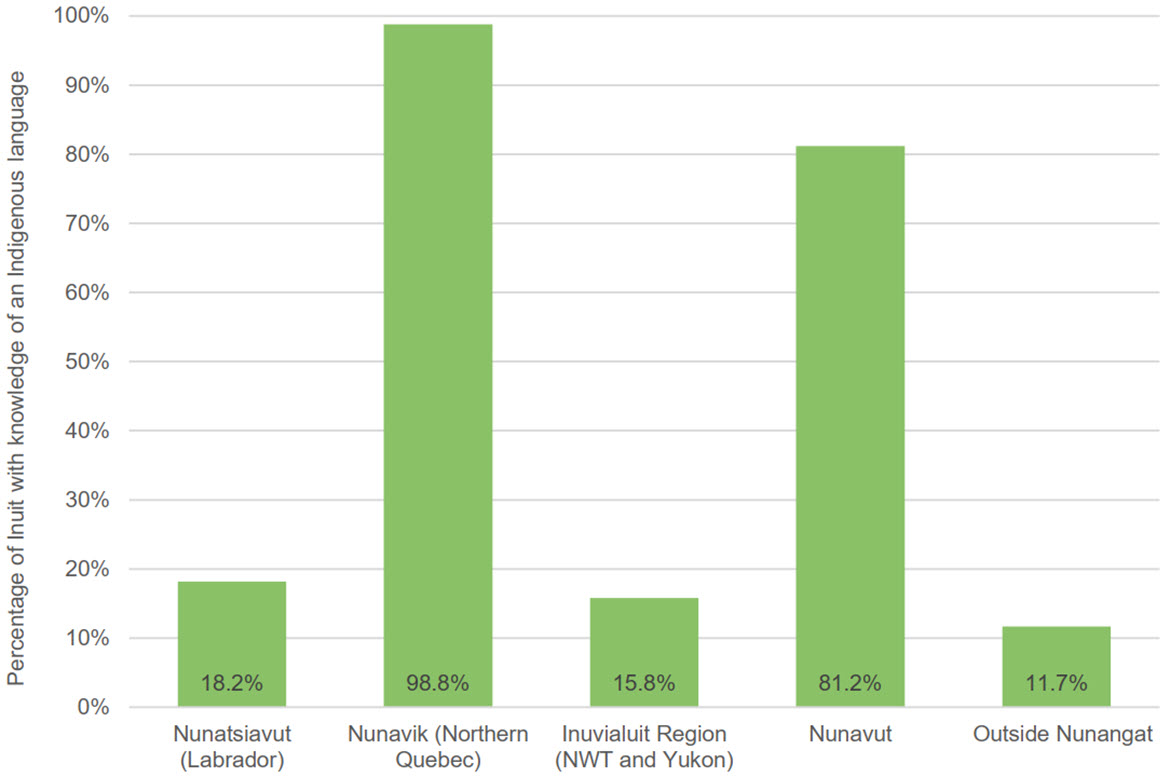

- Figure 60: Percentage of Inuit with knowledge of an Indigenous language, 2021, by region

- Figure 61: Percentage of Indigenous populations with knowledge of an Indigenous language, 2021, by gender, Canada

- Figure 62: Percentage of Indigenous populations with knowledge of an Indigenous language, 2021, aged 0 to 19 and aged 20+, Canada

- Figure 63: Custody admissions associated with Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in 2021 to 2022 as a percentage of their respective 2021 Census populations, Canada

- Figure 64: Percentage of custody admissions of individuals with Indigenous and non-Indigenous identity, 2016 to 2017 to 2020 to 2021, Canada

- Figure 65: Comparison of total and urban employment rates, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

Executive summary

Keywords: Indigenous Peoples, First Nations, Inuit, Métis, income, employment, family, culture, Indigenous languages, housing, foster care, justice, incarceration.

This report serves as a compendium to the Department's Annual Report to Parliament and provides an update on the 2020 report using data from the 2021 census cycle. It provides a broad overview of the socio-economic gaps between First Nations, Inuit and Métis populations and the non-Indigenous population in Canada. It covers a wide range of social and economic variables that can be linked primarily to data collected as part of the Census of Population. It highlights not only the gaps that exist today, but also the evolution of those gaps over time. The report also acknowledges that while progress has been made, much work remains to address the ongoing challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples and communities and to advance meaningful reconciliation.

In Canada, the Census of Population is conducted every five years. In 2022, data from the 2021 Census of Population were made available. This report focuses on a subset of these data and examines indicators related to income, employment, education, housing, foster care and Indigenous languages. Indicators related to incarceration are also examined using data from the most recent Adult Correctional Services Survey. As new data on the health domains included in the 2020 report have yet to be published, the health indicators are excluded from this report.

Indigenous Peoples in Canada face significant and long-standing socio-economic gaps when compared to the non-Indigenous population. These gaps have been shaped by a long history of colonialism, discrimination and marginalization, which have had a profound impact on Indigenous people and continue to affect their lives today. Although gaps remain, significant work is being done to narrow them and improve conditions. Continued measurement of these socio-economic gaps is important as it helps determine whether progress is being made over time. It can also help demonstrate whether existing programs and policies are properly designed and resourced. Lastly, it can help ensure accountability of those who design and implement programs, policies and calls for reflection to clearly and transparently define what progress means.

Overall, median individual income was higher in 2020Footnote 1 than in 2015 for all Indigenous groups, even after accounting for inflation. Although a similar proportion of individuals were employed compared to 2016, those who were employed made more, bringing home an additional $800 to $4,200 a year in income after adjusting for inflation. Increased income means fewer low-income households. Between the non-Indigenous population and each of the Indigenous groups, there was a clear narrowing of gaps, by 31.8 to 46.5%. The total number of Indigenous people living in a low-income situation dropped from 471,560 in 2015 to 335,560 in 2020. Overall, 136,000 fewer Indigenous people (60,190 Registered Indians living on reserve, 45,030 Registered Indians living off reserve, 8,975 Non-Status Indians, 2,840 Inuit and 18,965 Métis) were living in a low-income situation over 2015. In addition to contextualizing the historic implications of the pandemic on the socio-economic well-being of all Canadians, Census 2026 will be important to determine whether there have been lasting changes in these gaps beyond the availability of government benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Improving Indigenous education is a crucial step towards closing the socio-economic gaps and achieving substantive equality in recognizing that additional service supports may be required to enable Indigenous children to achieve equal outcomes. Among those 25 to 64 years of age with at least a high school education, a small narrowing of the gaps was observed for Registered Indians living off reserve and Non-Status Indians, while a large narrowing of the gap was seen for Métis. In total, there were 80,280 more Indigenous people with a high school education in 2021 (925 Registered Indians living on reserve, 26,150 Registered Indians living off reserve, 25,545 Non-Status Indians, 1,730 Inuit and 25,930 Métis). Increases in high school completion are important as it often represents a critical step to employment and higher education. From 2016 to 2021, there was a widening of the gap for all Indigenous groups in the proportion of the population with a university degree. Although an additional 47,980 Indigenous people (4,985 Registered Indians living on reserve, 14,630 Registered Indians living off reserve, 9,200 Non-Status Indians, 890 Inuit and 18,275 Métis) obtained a university education over 2016, the non-Indigenous population saw greater gains in university completion during the same time period.

Housing quality and conditions generally improved for Indigenous people from 2016 to 2021; however, the narrowing of the gap in the proportion of dwellings that were crowded was due in part to increases in crowding for the non-Indigenous population. Overall, the total number of Indigenous households experiencing crowding was relatively flat from 2016 (25,220 dwellings) to 2021 (25,345 dwellings). Both Métis and Non-Status Indians had lower proportions of crowded dwellings than the non-Indigenous population in 2016 and 2021. There were also substantial improvements in the proportion of dwellings requiring major repairs. From 2016 to 2021, there were 3,715 fewer dwellings associated with Indigenous people that required major repairs.

Indigenous children continue to be overrepresented in foster care. The census data collection method identifies only children in foster care who reside in a private home. It excludes those in institutions, group homes or other care arrangements. The proportion of Registered Indians, Non-Status Indians and Métis children in foster care remained fairly stable over the period. There was an increase of almost one percentage point for Inuit children. In total, there were 17,410 Indigenous children in foster care in 2016 compared to 17,320 in 2021.

In addition to the socio-economic gaps, the declines in Indigenous language knowledge are noteworthy. In 2021, there were over 70 Indigenous languages spoken in Canada. For more than 20 (28.6%) of those languages, 500 or fewer people reported speaking them as their mother tongue. Overall, 243,155 individuals could conduct a conversation in an Indigenous language, 188,905 people reported having at least one Indigenous mother tongue and 182,925 reported speaking an Indigenous language at home at least on a regular basis. Indigenous languages are a vital part of Canada's cultural and linguistic diversity and are essential to Indigenous Peoples' identity, culture and well-being. Many of the Indigenous languages in Canada are endangered, at risk of extinction due to the impacts of colonialism, residential schools and ongoing discrimination.

Indigenous Peoples in Canada continue to be overrepresented in the criminal justice system, as both victims and offenders. Reporting on custody admissions is limited to a pan-Indigenous identifier. From 2016 to 2021, the percentage of Indigenous adults who entered a correctional facility for remand or who were sentenced to custody or a community supervision program increased slightly from 29.9% to 31.2%. However, the total number of these admissions decreased considerably during the same period, with the number of admissions for Indigenous adults dropping from 74,823 in 2016 to 46,633 in 2021, a difference of 28,190 people.

Income, employment, education, housing, foster care and incarceration are key areas in which Indigenous Peoples face systemic barriers and inequalities. Continued measurement of these gaps is crucial to inform policies and programs that aim to improve socio-economic conditions and reduce disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples. Furthermore, preserving Indigenous languages and promoting language revitalization initiatives can help foster appreciation for Indigenous cultures and maintain this vital component of Canada's linguistic and cultural landscape. Addressing socio-economic disparities and preserving Indigenous languages are essential components of reconciliation. These efforts contribute to the establishment of a more equitable and just society for all Canadians, promoting greater understanding and respect between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples.

Introduction

Each year, Indigenous Services Canada provides a report on:

- the socio-economic gaps between First Nations, Inuit, Métis and other Canadians and the measures taken by the Department to reduce those gaps; and

- the progress made towards the transfer of departmental responsibilities to Indigenous organizations as part of its obligations under the Department of Indigenous Services Act. The 2020 report provided a detailed overview of the demographic and socio-economic trends reported on through Statistics Canada's Census of Population.

This compendium report provides an update to the 2020 report using data from the 2021 census cycle. It provides a broad overview of the socio-economic gaps between First Nations, Inuit and Métis and the non-Indigenous population in Canada. It covers a wide range of social and economic variables, ranging from income and education to housing and language use. It highlights not only the gaps that exist today, but also the evolution of those gaps over time.

Method

A note on terminology

At the outset, we wish to acknowledge that some terms in this document may be offensive and problematic for certain individuals who will read this report. While the language that is used in Canada to describe and speak about Indigenous Peoples is evolving to be more respectful and reflective of how Indigenous Peoples and communities themselves choose to be identified, some pieces of legislation continue to use outdated and colonial terminology.

For example, Canada's Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes three distinct "aboriginal peoples of Canada", namely, "Indian, Inuit and Métis". The Government of Canada now uses the terms "Indigenous" and "First Nations". However, "Aboriginal" and "Indian" remain the legal terms that continue to be used in certain circumstances.

Also, as the Indian Act (PDF), a very outdated and colonial piece of legislation, continues to be in effect, terms such as "registered Indian" (also referred to as "status Indian") remain in use. As these remain accepted legal terms, for the purposes of this report, which requires reference to the Indian Act and its provisions and requires precision in terminology for statistical purposes, the legal terms will be used.

Indigenous Peoples is a collective name for the original peoples of North America and their descendants. More than 1.8 million people in Canada (5.0% of the population of Canada) self-identified as an Indigenous person on Canada's 2021 Census of Population. Indigenous Peoples are the fastest growing population in Canada. Between 2016 and 2021, the Indigenous population grew by 8.0%, while the non-Indigenous population grew by 5.4%. The Indigenous population is also the youngest in Canada: in 2021, 41.2% of Indigenous people were under the age of 25, compared to 27.3% of the non-Indigenous population.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of Indigenous populations across Canada. The figure includes the number of Indigenous individuals living in each province and territory, as well as the proportion of Indigenous Peoples in its overall population. Indigenous Peoples make up the largest proportion of the population in Nunavut (85.8%), the Northwest Territories (49.6%) and the Yukon Territory (22.3%), followed by Manitoba (18.1%) and Saskatchewan (17.0%).

The associated table indicates which proportion of the overall Indigenous population resides in each province and territory. Although Indigenous people comprise only 2.9% of Ontario's population, the province is home to the largest population of Indigenous people, with 406,585 individuals or 22.5% of the Indigenous population in Canada, followed by 16.1 and 15.7% in British Columbia and Alberta, respectively.

The Canadian Constitution recognizes three groups of Indigenous Peoples: First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. These are three distinct peoples with unique histories, languages, cultural practices and spiritual beliefs. Figure 2 shows how the composition of Indigenous populations varies across the provinces and territories. This figure also includes "Other Indigenous" which is comprised of those with multiple Indigenous identities and those who identify as a band member only.

Text alternative for Figure 1: Distribution and number of Indigenous people in Canada by province and territory, 2021

| Population size | Percentage of Region Population | Percentage of Indigenous Population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 46,545 | 9.3% | 2.6% |

| Prince Edward Island | 3,385 | 2.2% | 0.2% |

| Nova Scotia | 52,430 | 5.5% | 2.9% |

| New Brunswick | 33,300 | 4.4% | 1.8% |

| Quebec | 205,010 | 2.5% | 11.3% |

| Ontario | 406,585 | 2.9% | 22.5% |

| Manitoba | 237,190 | 18.1% | 13.1% |

| Saskatchewan | 187,890 | 17.0% | 10.4% |

| Alberta | 284,470 | 6.8% | 15.7% |

| British Columbia | 290,210 | 5.9% | 16.1% |

| Yukon | 8,810 | 22.3% | 0.5% |

| Northwest Territories | 20,035 | 49.6% | 1.1% |

| Nunavut | 31,390 | 85.8% | 1.7% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

Text alternative for Figure 2: Composition of the Indigenous population in Canada by province and territory, 2021

| Registered Indian | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Other Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 48.8% | 20.1% | 15.5% | 13.8% | 1.8% |

| Prince Edward Island | 43.3% | 27.5% | 5.3% | 22.9% | 1.2% |

| Nova Scotia | 35.2% | 23.1% | 2.1% | 37.9% | 1.8% |

| New Brunswick | 45.9% | 22.2% | 2.0% | 28.3% | 1.6% |

| Quebec | 37.4% | 26.7% | 7.6% | 26.9% | 1.4% |

| Ontario | 42.4% | 24.5% | 1.0% | 30.4% | 1.7% |

| Manitoba | 53.6% | 5.7% | 0.3% | 39.5% | 0.9% |

| Saskatchewan | 61.2% | 5.5% | 0.2% | 32.4% | 0.7% |

| Alberta | 44.5% | 10.8% | 1.0% | 42.3% | 1.4% |

| British Columbia | 47.2% | 18.9% | 0.6% | 31.5% | 1.9% |

| Yukon | 69.7% | 12.5% | 2.8% | 13.3% | 1.7% |

| Northwest Territories | 62.6% | 3.7% | 20.2% | 12.5% | 1.0% |

| Nunavut | 0.4% | 0.4% | 98.3% | 0.4% | 0.6% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

Note: "Other Indigenous" comprises those with multiple Indigenous identities and those who identify as a band member only.

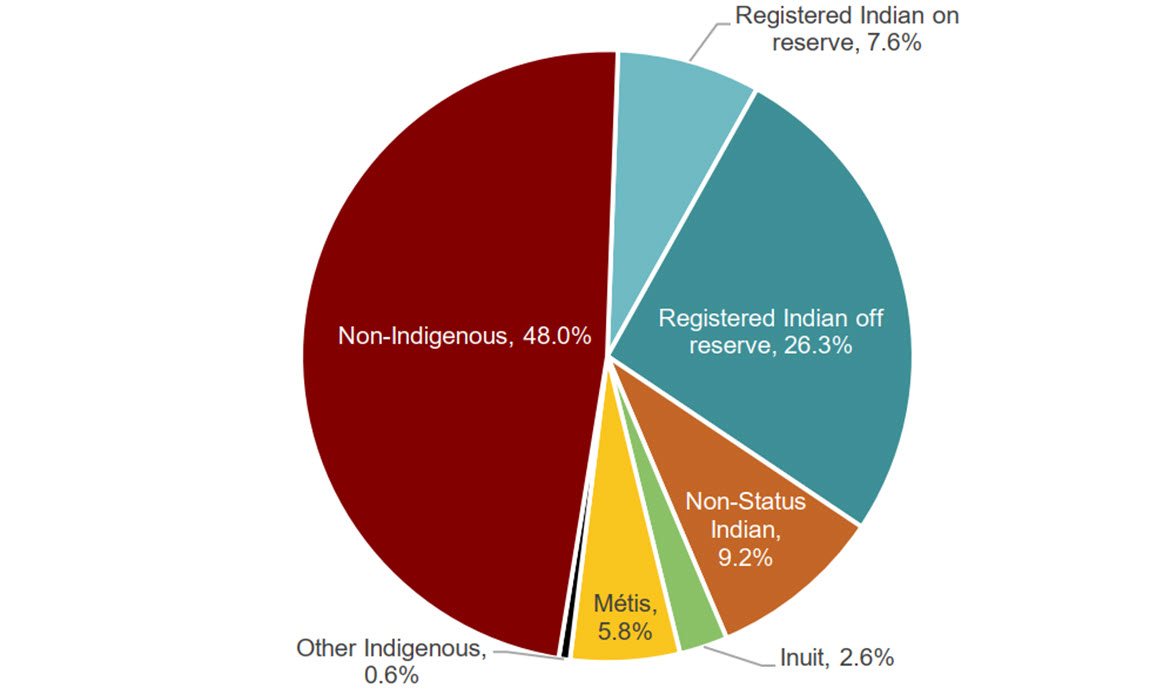

Composition of the Indigenous population in Canada, 2021

First Nations

- The term "First Nations" includes Registered Indians (also called Status Indians) and Non-Status Indians. Registered Indians are individuals registered as Indians under the Indian Act.

- According to the Census, there were 831,720 Registered Indians in Canada in 2021, comprising 46.0% of the Indigenous population. According to the Indian Register, which is an administrative list of all Registered Indians that is maintained by Indigenous Services Canada, there were 1,040,319 Registered Indians as of December 31, 2021.

- Indigenous Services Canada officially recognizes 619 First Nations in Canada, which represent more than 50 Nations and 50 Indigenous languages.

- Some First Nations reside on reserve. A reserve is a parcel of land for which legal title is held by the Crown (Government of Canada), for the use and benefit of a particular First Nation. There are 3,406 reserves in Canada.

- According to the 2021 Census of Canada, about 37.5% of Registered Indians live on reserve and 62.5% live off reserve. Overall, 48.0% of Registered Indians live in urban areas.

- Of the 883 populated census subdivisions associated with First Nations communities in the 2021 Census, 635 or 71.9% have less than 500 inhabitants while only 39 or 4.4% have more than 2,000 inhabitants.

- Non-Status Indians account for 16.3% of the total Indigenous population and live almost exclusively off reserve (97.4%). Overall, 75.0% live in urban areas.

Inuit

- Inuit are Indigenous people of the Arctic. The word Inuit means "the people" in the Inuit language of Inuktitut. The singular of Inuit is Inuk.

- According to the Census, Canada's self-identified Inuit population was 69,705 in 2021, comprising 0.2% of the national population and 3.9% of the Indigenous population. The majority (69.7%) live in Inuit Nunangat, which means "homeland", and 44.3% in Nunavut in particular.

- Inuit Nunangat comprises 51 communities across four regions: Inuvialuit Settlement Region (Northwest Territories and Yukon), Nunavut, Nunavik (northern Quebec), and Nunatsiavut (Labrador).

- In the 2021 Census, just over four-fifths (81.2%) of Inuit in Canada reported that they were enrolled under or were a beneficiary of an Inuit land claims agreement. Of Inuit who were enrolled under or were a beneficiary of an Inuit land claim agreement:

- 32,620 (57.6%) came under the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement;

- 13,235 (23.4%) came under the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement;

- 5,920 (10.5%) came under the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement; and

- 4,860 (8.6%) came under the Inuvialuit Final Agreement.

- Most Inuit who are not enrolled under or are not a beneficiary of a land claim agreement (13,080) live outside Inuit Nunangat (86.4%).

Métis

- Of the 624,220 Canadians who self-identified as Métis in the 2021 Census, 224,655 (36.0%) reported membership in a Métis organization or Settlement. Four-fifths (79.8%) reported being a member of one of the five signatories to the Canada-Métis Nation Accord.

- In 2021, the Métis Nation of Alberta had the largest membership reported among Métis organizations, at 45,350, followed closely by the Manitoba Métis Federation, at 43,920, and then by the Métis Nation of Ontario (36,240), Métis Nation British Columbia (27,140) and Métis Nation-Saskatchewan (26,700).

- 3,540 people reported being a member of one of the eight Métis Settlements of Alberta.

Measuring the socio-economic gaps

Why measurement is important

First, continued measurement helps determine whether progress is being achieved over time. Second, ongoing measurement can help demonstrate whether existing programs and policies are properly designed and resourced, and whether there are program and policy gaps that must be addressed. Third, by tracking program and policy performance and identifying gaps, measurement can help ensure accountability of those who design and implement programs and policies. Finally, measurement calls for reflection to clearly and transparently define what progress means. By stimulating conversation and inviting challenge, the iterative process of defining how to measure progress focuses attention on the things that truly matter.

What is important to measure

The socio-economic dimensions addressed in this report were originally selected and analyzed as part of the 2020 Annual Report to Parliament based on a review of the various socio-economic wellness frameworks being used around the world. This compendium report provides an update on these measures to determine the progress that has been made towards narrowing the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada.

Examining gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations helps contextualize the extent of the differences between groups. Without a basis for comparison, raw statistics are difficult to interpret. It is sometimes suggested that focusing on gaps between different populations is inappropriate as it may involve an implicit value judgment. It suggests that the lower-scoring population should aspire to the level of the higher-scoring population on a particular indicator, even if the indicator is of little importance to the lower-scoring population. This is a fair critique and is why the current report focuses on key socio-economic indicators that appear regularly in Indigenous wellness frameworks and that are recognized internationally as important to quality of life in most cultural contexts.

The indicators

The complete set of indicators addressed in this report includes the following.

| Domain | Indicator | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Income | Median income Median total income for the working-age population |

Census of Population, Canada, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 |

| Poverty Percentage of the population that lived in a low-income situation in the year preceding the Census |

Census of Population, Canada, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 | |

| Employment | Employment rate Percentage of the working-age population that was employed on Census reference day |

Census of Population, Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 |

| Median employment income Median employment income received by the working-age population in the year prior to the Census |

Census of Population, Canada, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 | |

| Education | High school completion Percentage of the working-age population that had a high school diploma or that had a post-secondary credential even though they did not complete high school |

Census of Population, Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 |

| University completion Percentage of the working-age population with a university degree |

Census of Population, Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 | |

| Family | Foster care Percentage of children and youth aged 0 to 17 in foster care within a private household |

Census of Population, Canada, 2011, 2016, 2021 |

| Culture | Indigenous language knowledge Percentage of the population that is able to carry on a conversation in an Indigenous language |

Census of Population, Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 |

| Housing | Crowding Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded (i.e., having more than one person per room) |

Census of Population, Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 |

| State of repair Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair |

Census of Population, Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021 | |

| Justice | Incarceration Custodial admissions as a percentage of the Indigenous and the non-Indigenous population and overrepresentation of Indigenous people in custodial admissions |

Adult Correctional Services survey, 2013 to 2014, 2014 to 2015, 2015 to 2016, 2016 to 2017, 2017 to 2018, 2019 to 2020, 2020 to 2021 |

The 2020 Annual Report to Parliament also included a health domain with a number of indicators linked to vital statistics such as life expectancy and infant mortality. Although new publications on these critical indicators are in development, no new data had been published on these indicators as of the time this report was drafted. Therefore, the health domain and its indicators will be omitted from this iteration of the report and will be reported in a future version once the data are available.

Limitations of the data

Data for the first six sets of indicators (from income to housing) are taken from the Census of Population that is conducted every five years and enumerates private dwellings and the people who reside within them. This robust source of socio-economic information remains the cornerstone of data because of its unparalleled ability to support distinctions-based, cross-time analyses for all of Canada, including reserves and the territories.

Despite its richness, the Census has some important limitations. For example, Indigenous people are classified in the Census as Indigenous (or not) based on self-identification, which can be imperfect given variations in how respondents interpret or understand the Indigenous identity questions, as well as their individual choices respecting whether and how to self-identify as an Indigenous person.

Each of the Indigenous identities is determined through a combination of census questions and is subject to interpretation. For example, Statistics Canada looks only at question 24: "Is this person First Nations, Métis or Inuk (Inuit)?" As Indigenous Services Canada is responsible for maintaining the Indian Register, there is a greater emphasis on the importance of identifying Registered versus Non-Status Indians. Indigenous Services Canada considers an individual's response to question 26: "Is this person a Status Indian (Registered or Treaty Indian as defined by the Indian Act of Canada)?" before question 24 (identity). This seemingly small difference can lead to differences in how the Indigenous identity groups are reported.

Another important limitation is that the Census of Population includes a relatively narrow range of socio-economic indicators and does not capture the various other dimensions of well-being that are important from an Indigenous perspective. For example, the National Outcome-Based Framework includes indicators on governance, the environment, participation in cultural activities, relationship to the land and systemic racism. It also counts only those residing in private dwellings, which leads to an undercount as it inherently excludes those who reside in institutions, who are transient or who are experiencing homelessness.

The 2021 Census was further complicated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which profoundly impacted the way data were collected for this census cycle. The 2021 Census was launched on May 11, 2021. In order to mitigate the circumstances created by the pandemic and prevent further spread of COVID-19 in First Nations and Inuit communities, Statistics Canada implemented a data collection approach that differed from previous censuses. To minimize face-to-face interactions, the 2021 Census data collection initially prioritized self-enumeration (paper questionnaires, online) rather than in-person interviews with an enumerator. In addition to the constraints caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the uncovering of burial sites at former residential schools as well as the forest fires in northern Ontario and the western provinces further impacted participation by Indigenous communities and their residents. In order to mitigate the impact of low participation in the 2021 Census, Statistics Canada revised its data collection strategy in July 2021 and sent travel teams of enumerators to various regions across Canada. Engagement efforts were bolstered through an expanded Indigenous Liaison Program at Statistics Canada, and efforts were made to hire census staff locally within communities.

All data collection activities for the 2021 Census ceased on September 24, 2021. Despite all efforts by Statistics Canada, a total of 63 census subdivisions defined as reserves and settlements were incompletely enumerated. Previously, the number of incompletely enumerated reserves had declined; for example, it was 30 in 2001, 22 in 2006, 36 in 2011 and 14 in 2016. In 2021, the estimated census response rate in Indigenous and northern communities was 85.6%. Comparatively, the overall census response rate was 98% in 2021, and the response rate in Indigenous communities was 92% in 2016.

Given the larger number of First Nations communities that were incompletely enumerated in 2021, Statistics Canada has urged caution when comparing variables that are strongly tied to First Nations reserves. For example, Indigenous language knowledge is typically substantially higher among those residing on a reserve. As some of those responses were not captured during this census data collection cycle, there is an increased risk of potentially erroneous or confounding conclusions. Any potential drop in Indigenous language knowledge may stem from a real drop in the number of Indigenous language speakers or from the fact that fewer Indigenous language speakers were counted this census and are missing from the overall findings.

As we move beyond the census to seek other sources of data on justice, the persistent gaps in data on Indigenous populations become more evident as data are limited to a pan-Indigenous identifier. Where such limitations exist, the best data available are used to illustrate the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations.

The analysis

To the extent possible, this analysis is distinctions-based. Data are presented for the three main distinctions groups: First Nations, Inuit and Métis. First Nations data are further disaggregated, given the significant differences in socio-economic outcomes that are known to exist among the following groups: Registered Indians living on reserve, Registered Indians living off reserve and Non-Status Indians. Where possible, data for the past 20 years have been included to illustrate how socio-economic gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations have evolved.

Regional analyses are also provided. Notably, some very small populations of First Nations and Métis in the territories are also the populations experiencing the largest gaps relative to the non-Indigenous population. Because statistics based on very small populations are less reliable and can create a skewed image of overall trends, one option would be to exclude them from broader analyses and/or discuss them separately. In the interest of transparency, however, it was decided to retain these small populations as part of the general analysis. Readers are encouraged to interpret statistics for small populations with caution, especially when data are further broken down by gender, age or other variables.

For the first time in census history, 2021 marks the shift to reporting on gender rather than biological sex. A new question on gender was included in the 2021 Census to reflect a growing social and legislative recognition of transgender and non-binary people. Gender identity refers to a person's internal and individual experience with gender. It may not be visible to others and it may not align with socially constructed gender norms. A person may refer to their gender identity in a multitude of ways including Woman, Man, Non-binary, Two-Spirit, Pangender, Agender, Gender Queer, Gender Fluid, Transgender or Cisgender.

The 2021 Census is the first census to provide data on transgender people and non-binary people. Census 2021 allowed individuals to write in responses other than male or female for the gender question. All these responses were condensed into a single non-binary gender for reporting purposes. Even with this amalgamation, the number of non-binary people is still quite small. Given this, Statistics Canada further aggregates data into a two-category gender variable when necessary to protect the confidentiality of responses provided. In these cases, individuals in the category "non-binary persons" are distributed in the other two gender categories and are denoted by the "+" symbol. "Men+" includes men (and/or boys), as well as half of non-binary persons. "Women+" includes women (and/or girls), as well as half of non-binary persons. Detailed analyses by gender are provided where feasible.

Measuring the gap

A number of different approaches can be taken to assess the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations. For instance, the difference between groups (e.g., there was a difference of X % or Y dollars between group A and B) can be used to get a sense of where the gaps exist. However, limiting analysis to look only at the differences between groups can hinder the comparability between groups and indicators over time. Another choice is to examine the relative variation. The % change in gaps can be calculated, allowing for the relative size of the changes to be compared.

In this report, the gap between the total Indigenous population (or Indigenous group) and the non-Indigenous population is provided for each indicator. The gap is reported as the difference between the two populations. An analysis of the % change in the gap from 2016 to 2021 is also presented and discussed where feasible.

A common approach to interpreting % change is to use Cohen's d effect size measure as a guide. According to Cohen's conventions, a small effect size is typically defined as a Cohen's d of 0.2, a medium effect size as a Cohen's d of 0.5, and a large effect size as a Cohen's d of 0.8. Using these conventions, a % change of 5% would be considered a small effect size, a % change of 12.5% would be considered a medium effect size, and a % change of 20% or more would be considered a large effect size.

In the spirit of accessibility and transparency, the goal of this report is to provide a large volume of data to inform partners and stakeholders. For each figure, a brief summary of the more notable findings is presented. The full data tables are available in Appendix A and readers are encouraged to engage with the data. To obtain a copy of the data associated with this report or to obtain additional census data related to Indigenous Peoples in Canada, please contact the Indigenous and Northern Statistics Team (INSTAT) at instat@sac-isc.gc.ca.

Findings

Income – Median individual income

Median income is a well-established measure of material well-being. Although it does not capture an individual's assets, median income is one way of estimating a person's wealth. Median individual income refers to a person's total income before tax from all sources including market income (such as employment wages) and government transfers (such as Old Age Security pension and other government benefit programs). In the census, income information is provide through tax records from the previous calendar year. For example, for data collected in the 2021 Census, income from January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020 is reported. Similarly, for Census 2016, income data is based on 2015.

Median individual income includes government benefits, which is of particular importance for 2020. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of new government benefits were offered such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). Statistics Canada has analyzed these most recent census data and concluded that "the decrease [in poverty rates] was mostly driven by increased government transfers and temporary pandemic-related benefits."

For a full list of all data tables relevant to median income, please see Appendix A, tables A1.1 to A1.6.

Text alternative for Figure 3: Median individual income, 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $32,000 | $42,000 | $43,200 | $42,800 | $48,800 | $50,400 |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- Median individual income for individuals aged 25 to 64 was lower for all Indigenous groups compared to the non-Indigenous population ($50,400).

- Registered Indians living on reserve had the largest gap in median individual income ($32,000) with relative to the non-Indigenous population, at $18,400.

- The gaps in median individual income for Registered Indians living off reserve ($8,400), Inuit ($7,600) and Non-Status Indians ($7,200) relative to the non-Indigenous population were similar in size.

- For Métis, median individual income varied little relative to the non-Indigenous population with a gap of only $1,600.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A1.1.

Text alternative for Figure 4: Median individual income 2005 to 2020 (adjusted), Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | $17,700 | $27,700 | $30,800 | $31,000 | $35,200 | $41,800 |

| 2010 | $18,200 | $32,300 | $34,700 | $34,200 | $40,300 | $44,400 |

| 2015 | $22,100 | $35,400 | $37,400 | $36,000 | $44,300 | $46,600 |

| 2020 | $32,000 | $42,000 | $43,200 | $42,800 | $48,800 | $50,400 |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2006 to 2021 Census of Population.

Note: The dollar values have been adjusted for inflation and are stated in terms of their value in 2020.

- In the last 15 years, there has been a notable closing of the gap in median individual income between each of the Indigenous groups and the non-Indigenous population.

- The most striking reduction in the income gap occurred among Registered Indians living on reserve, improving from the largest gap of $26,200 in 2010 to $18,400 in 2020, which represents a reduction of $7,770.

- Registered Indians off reserve had the largest change in dollars, with median individual income increasing from $27,700 in 2005 to $42,000 in 2020, an increase of $14,300.

- The median income gap narrowed to a lesser extent for Non-Status Indians, from $11,000 in 2005 to $7,200 in 2020; for Inuit, from $10,800 to $7,600; and for Métis, from $6,600 to $1,600.

- This narrowing of gaps is likely due in part to the increased government transfers in 2020 as a result of supports made available during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results from the 2026 Census will be essential to assess if these improvements are sustainable long term.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A1.2.

Text alternative for Figure 5: Median individual income, 2020, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | $44,800 | $42,800 | $43,200 | $46,000 |

| Prince Edward Island | $38,400 | $41,200 | $34,800 | $45,600 |

| Nova Scotia | $32,400 | $43,600 | $39,600 | $45,600 |

| New Brunswick | $35,600 | $40,400 | $36,800 | $45,200 |

| Quebec | $44,800 | $46,800 | $45,200 | $50,000 |

| Ontario | $32,400 | $44,000 | $42,400 | $50,400 |

| Manitoba | $28,000 | $36,400 | $40,000 | $48,800 |

| Saskatchewan | $27,000 | $39,200 | $41,200 | $53,600 |

| Alberta | $31,200 | $42,400 | $45,900 | $54,400 |

| British Columbia | $32,400 | $42,400 | $44,000 | $50,000 |

| Yukon | $50,800 | $62,000 | $68,500 | |

| Northwest Territories | $39,200 | $47,600 | $69,000 | $89,000 |

| Nunavut | $100,000 | $92,000 | $116,000 |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- The national picture of the gap in median income between First Nations and the non-Indigenous population masks important regional differences.

- Registered Indians living on reserve in Newfoundland and Labrador, for example, had a median income that was almost equal to that of the non-Indigenous population, while those in Saskatchewan had a median income that was only half of the median income of Saskatchewan's non-Indigenous population, a difference of approximately $26,600 annually.

- For Registered Indians living off reserve, the smallest gap in median individual income was found in Nova Scotia ($2,000) and the largest in the Northwest Territories ($41,400).

- Among Non-Status Indians, Newfoundland and Labrador had the smallest gap at $2,800 compared to the largest in Nunavut ($24,000) followed by the Northwest Territories ($20,000).

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A1.3.

Text alternative for Figure 6: Median individual income, 2020, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

| Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | $48,400 | $46,000 |

| Prince Edward Island | $51,600 | $45,600 |

| Nova Scotia | $44,000 | $45,600 |

| New Brunswick | $40,400 | $45,200 |

| Quebec | $47,600 | $50,000 |

| Ontario | $49,200 | $50,400 |

| Manitoba | $47,600 | $48,800 |

| Saskatchewan | $49,200 | $53,600 |

| Alberta | $50,800 | $54,400 |

| British Columbia | $48,400 | $50,000 |

| Yukon | $61,600 | $68,500 |

| Northwest Territories | $79,000 | $89,000 |

| Nunavut | $125,000 | $116,000 |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- Regional differences were less pronounced among Métis than First Nations, as their median individual incomes were much closer to and, in some areas, above those of their non-Indigenous counterparts.

- Of note, the Métis populations in Nunavut (110 people) and Prince Edward Island (770 people) were small, and the high incomes observed in these areas are more likely a result of the effects of the small population size, not a reflection of robust area differences.

- The largest gap in median individual income ($10,000) between Métis and the non-Indigenous population was found in the Northwest Territories.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A1.4.

Text alternative for Figure 7: Median individual income, 2020, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by Inuit region

| Nunatsiavut (Labrador) | Nunavik (Northern Quebec) | Inuvialuit Region (Northwest Territories and Yukon) | Nunavut | Outside of Inuit Nunangat | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inuit | Non-Indigenous | Inuit | Non-Indigenous | Inuit | Non-Indigenous | Inuit | Non-Indigenous | Inuit | Non-Indigenous |

| $40,400 | $63,600 | $45,600 | $84,000 | $41,600 | $97,000 | $40,400 | $116,000 | $44,000 | $50,400 |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- Median individual income among the Inuit population differed marginally across regions, ranging from $40,400 in both regions of Nunatsiavut and Nunavut to $45,600 in the Nunavik region of Northern Quebec.

- The gaps in median individual income relative to the non-Indigenous population in Inuit Nunangat's four constituting regions were sizable, ranging from $23,200 in Nunatsiavut to $75,600 in Nunavut.

- It is worth noting that the wide gaps reflect the high median incomes of the non-Indigenous population living in Inuit Nunangat. Outside of Inuit Nunangat, the median income of the non-Indigenous population was much lower, and the gap was comparatively narrow at $6,400.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A1.5.

Text alternative for Figure 8: Median individual income, 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by gender, Canada

| Men+ Income | Women+ Income | |

|---|---|---|

| Registered Indian on reserve | $27,400 | $36,800 |

| Registered Indian off reserve | $44,000 | $41,200 |

| Non-Status Indian | $47,200 | $40,800 |

| Inuit | $39,600 | $45,200 |

| Métis | $55,200 | $44,000 |

| Non-Indigenous | $56,800 | $45,200 |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

Note: Given that the non-binary population is small, Statistics Canada implemented a method producing a two-category gender variable to prevent disclosure of identifiable data for lower levels of geography. Consequently, information will be disseminated using the following categories: Men+, Women+. Individuals in the "non-binary persons" category are distributed in the other two gender categories and are denoted by the "+" symbol.

- In 2020, the median individual income for non-Indigenous men+ was higher than the median income for non-Indigenous women+ by approximately $11,600.

- By contrast, Inuit women+ had a higher median income (by $5,600) than Inuit men+. Among Registered Indians living on reserve, the median income of women+ was $9,400 higher than that of men+.

- The gap in median individual income relative to the non-Indigenous population was highest among Registered Indian men+ on reserve, at $29,400, and lowest among Métis men+, at $1,600.

- The median individual income of Inuit women+ was equivalent to that of the non-Indigenous group (no gap), while Registered Indian women+ living on reserve had the largest gap relative to the non-Indigenous group, at $8,400.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A1.6.

Measuring the gap

| 2015 | 2020 | Five-Year Change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | Gap | Income | Gap | Income | Percentage change in gap | |

| Registered Indian on reserve | $22,100 | -$24,500 | $32,000 | -$18,400 | $9,900 | -24.9% |

| Registered Indian off reserve | $35,400 | -$11,200 | $42,000 | -$8,400 | $6,600 | -25.0% |

| Non-Status Indian | $37,400 | -$9,200 | $43,200 | -$7,200 | $5,800 | -21.7% |

| Inuit | $36,000 | -$10,600 | $42,800 | -$7,600 | $6,800 | -28.3% |

| Métis | $44,300 | -$2,300 | $48,800 | -$1,600 | $4,500 | -30.4% |

| Non-Indigenous | $46,600 | $50,400 | $3,800 | |||

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2016 to 2021 Census of Population. Note: The dollar values for 2015 have been adjusted for inflation and are stated in terms of their value in 2020. |

||||||

- Overall, in all cases, the gaps between the Indigenous group and the non-Indigenous population shrunk between 2015 and 2020.

- There was a large narrowing of the gap in individual median income for all Indigenous groups compared to the non-Indigenous population, with the largest change occurring among Métis, at 30.4%.

| Men+ | Women+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income change | Percentage change in gap | Income change | Percentage change in gap | |

| Registered Indian on reserve | $10,360 | -12.1% | $13,500 | -38.7% |

| Registered Indian off reserve | $6,100 | 1.6% | $11,600 | -45.9% |

| Non-Status Indian | $6,500 | -2.0% | $10,600 | -35.3% |

| Inuit | $7,000 | -3.9% | $11,800 | -100.0% |

| Métis | $5,200 | 220.0% | $9,500 | -52.0% |

| Non-Indigenous | $6,300 | $8,200 | ||

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2016 to 2021 Census of Population. Note: The 2015 dollar values have not been adjusted for inflation. Given that the non-binary population is small, Statistics Canada implemented a method producing a two-category gender variable to prevent disclosure of identifiable data for lower levels of geography. Consequently, information will be disseminated using the following categories: Men+, Women+. Individuals in the "non-binary persons" category are distributed in the other two gender categories and are denoted by the "+" symbol. |

||||

- Generally, Indigenous women+ had substantially greater gains than Indigenous men+ in terms of closing the gap with their non-Indigenous counterparts.

- For Indigenous men+, the gaps in median individual income relative to the non-Indigenous population remained relatively stable between 2015 and 2020, with the exception of Métis for whom the gap more than doubled (220.0%) from $500 in 2015 to $1,600 in 2020.

- All Indigenous women+ saw a large narrowing of the gap between 2015 and 2020, particularly Inuit women+ for whom the gap with their non-Indigenous counterparts closed entirely (-100.0%).

- It is important to acknowledge that the general narrowing of the gaps may stem from the increased availability of government benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A1.6.

Low-income measure after tax

The low-income measure after tax (LIM-AT) is one way to assess the level of poverty in a population. A person is considered to be living in a low-income situation if they are part of a household whose total income (after tax) is less than half of the national median household income, adjusted for household size. The low-income threshold in 2020 was $26,503 for a single person and $53,005 for a family of four. Overall, more than 335,000 Indigenous people were living in a low-income situation in 2020 (Table 3). Data are based on the last full calendar year before the census (i.e., 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020). For a full list of all data tables relevant to the low-income measure after tax, please see Appendix A, tables A2.1 to A2.6.

| 2015 | 2020 | Difference | Percentage Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered Indian on reserve | 157,785 | 97,595 | -60,190 | -38.1% |

| Registered Indian off reserve | 147,970 | 102,940 | -45,030 | -30.4% |

| Non-Status Indian | 58,600 | 49,625 | -8,975 | -15.3% |

| Inuit | 14,330 | 11,490 | -2,840 | -19.8% |

| Métis | 92,875 | 73,910 | -18,965 | -20.4% |

| Non-Indigenous | 4,517,905 | 3,677,120 | -840,785 | -18.6% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2016 to 2021 Census of Population. |

||||

Text alternative for Figure 9: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

| Percentage | |

|---|---|

| Registered Indian on reserve | 31.3% |

| Registered Indian off reserve | 19.8% |

| Non-Status Indian | 16.8% |

| Inuit | 16.5% |

| Métis | 12.6% |

| Non-Indigenous | 10.7% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- All the Indigenous groups were more likely to live in a low-income situation than the non-Indigenous population (10.7%).

- The proportion of those living in a low-income situation was highest amongst Registered Indians, representing 31.3% of Registered Indians on reserve and 19.8% of Registered Indians off reserve.

- A slightly lower proportion of Non-Status Indians (16.8%) and Inuit (16.5%) were living in a low-income situation in 2020.

- Métis were closest to the proportion of the non-Indigenous population living in a low-income situation (12.6%).

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A2.1.

Text alternative for Figure 10: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2005 to 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 50.7% | 36.7% | 27.5% | 26.3% | 21.0% | 13.6% |

| 2010 | 54.1% | 31.9% | 25.3% | 22.9% | 19.5% | 14.6% |

| 2015 | 47.7% | 30.3% | 25.2% | 22.3% | 17.3% | 13.8% |

| 2020 | 31.3% | 19.8% | 16.8% | 16.5% | 12.6% | 10.7% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- The likelihood of living in a low-income situation decreased between 2005 and 2020 for each Indigenous group, particularly Registered Indians on reserve. That group had a total decline of 19.4 percentage points from 2005 (50.7%) to 2020 (31.3%).

- The proportion of Registered Indians living off reserve in a low-income situation dropped considerably, from 36.7% in 2005 to 19.8% in 2020, a decline of 16.9 percentage points.

- The proportion of individuals living in a low-income situation among Non-Status Indians, Inuit and Métis also fell, from 27.5 to 16.8% (10.7 percentage points), 26.3 to 16.5% (9.8 percentage points), and 21.0 to 12.6% (8.4 percentage points), respectively.

- Although the availability of government benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed to these reductions, the downward trend was also notable between 2005 and 2015 prior to the pandemic and any related supports. Census 2026 will be important in determining if these recent reductions are long lasting.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A2.2.

Text alternative for Figure 11: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2020, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 12.4% | 15.9% | 15.0% | 15.2% |

| Prince Edward Island | 21.8% | 20.3% | 18.3% | 13.7% |

| Nova Scotia | 35.2% | 17.5% | 20.4% | 14.6% |

| New Brunswick | 24.0% | 16.3% | 21.1% | 14.0% |

| Quebec | 14.8% | 16.5% | 15.4% | 11.8% |

| Ontario | 33.7% | 16.8% | 16.0% | 9.9% |

| Manitoba | 38.5% | 30.6% | 31.0% | 11.5% |

| Saskatchewan | 40.9% | 26.6% | 28.8% | 10.7% |

| Alberta | 29.8% | 19.5% | 15.2% | 8.6% |

| British Columbia | 25.0% | 15.9% | 13.9% | 10.5% |

| Yukon | 12.9% | 12.7% | 6.4% | |

| Northwest Territories | 18.4% | 11.3% | 6.7% | 2.9% |

| Nunavut | 8.0% | 9.1% | 3.4% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- For Registered Indians living on reserve, the highest proportion of individuals living in a low-income situation was observed in Saskatchewan (40.9%) and Manitoba (38.5%), and the lowest in Newfoundland and Labrador (12.4%).

- Among Registered Indians living off reserve, the highest proportions of individuals living in a low-income situation were in Manitoba (30.6%) and Saskatchewan (26.6%), and the lowest in Nunavut (8.0%) and the Northwest Territories (11.3%).

- The same trend applied to Non-Status Indians, where the highest proportions of individuals living in a low-income situation were in Manitoba (31.0%) and Saskatchewan (28.8%), and the lowest in the Northwest Territories (6.7%).

- The gaps between First Nations and non-Indigenous people living in a low-income situation varied markedly across the provinces and territories. These gaps were consistently highest for Registered Indians living on and off reserve as well as Non-Status Indians in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and were lowest for those in Newfoundland and Labrador.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A2.3.

Text alternative for Figure 12: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2020, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, by region

| Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 10.2% | 15.2% |

| Prince Edward Island | 13.6% | 13.7% |

| Nova Scotia | 14.0% | 14.6% |

| New Brunswick | 16.4% | 14.0% |

| Quebec | 15.9% | 11.8% |

| Ontario | 11.3% | 9.9% |

| Manitoba | 14.5% | 11.5% |

| Saskatchewan | 14.5% | 10.7% |

| Alberta | 11.4% | 8.6% |

| British Columbia | 10.7% | 10.5% |

| Yukon | 5.1% | 6.4% |

| Northwest Territories | 6.8% | 2.9% |

| Nunavut | 3.4% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- The proportion of Métis living in a low-income situation varied across Canada.

- Métis were less likely than their non-Indigenous counterparts to live in a low-income situation in Newfoundland and Labrador (10.2%) and Yukon (5.1%).

- In Prince Edward Island (13.6%), Nova Scotia (14.0%) and British Columbia (10.7%), the proportion of Métis and non-Indigenous people living in a low-income situation was on par.

- The proportion of Métis living in a low-income situation outpaced that of the non-Indigenous population in all other regions.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A2.4.

Text alternative for Figure 13: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2020, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, by Inuit region

| Nunatsiavut (Labrador) | Nunavik (Northern Quebec) | Inuvialuit Region (Northwest Territories and Yukon) | Nunavut | Outside Inuit Nunangat | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inuit | Non-Indigenous | Inuit | Non-Indigenous | Inuit | Non-Indigenous | Inuit | Non-Indigenous | Inuit | Non-Indigenous |

| 22.2% | 13.3% | 15.1% | 5.8% | 16.1% | 5.7% | 16.7% | 3.4% | 16.5% | 10.7% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- The proportion of Inuit living in a low-income situation was highest in Nunatsiavut (22.2%) and lowest in Nunavik (15.1%).

- The gap between Inuit and non-Indigenous people living in a low-income situation varied considerably. Inside of Inuit Nunangat, the gap was highest in Nunavut (13.3 percentage point difference) and lowest in the Nunatsiavut region (8.9 percentage point difference).

- Conversely, for Inuit residing outside the Inuit Nunangat, the gap between Inuit and non-Indigenous people living in a low-income situation was 5.8 percentage point difference.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A2.5.

Text alternative for Figure 14: Percentage living in a low-income situation, 2020, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, by gender, Canada

| Men+ Percentage | Women+ Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Registered Indian on reserve | 31.2% | 31.4% |

| Registered Indian off reserve | 18.4% | 21.0% |

| Non-Status Indian | 16.3% | 17.3% |

| Inuit | 16.1% | 16.8% |

| Métis | 11.9% | 13.3% |

| Non-Indigenous | 10.1% | 11.2% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

Note: Given that the non-binary population is small, Statistics Canada produced a two-category gender variable that was applied to prevent disclosure of identifiable data for lower levels of geography when necessary. Consequently, information will be disseminated using the following categories: Men+, Women+. Individuals in the "non-binary persons" category are distributed in the other two gender categories and are denoted by the "+" symbol.

- Although women+ were more likely than men+ to be living in a low-income situation, the differences were relatively small when compared to the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations.

- The proportion of Indigenous people living in a low-income situation ranged from 11.9% for Métis men+ to 31.2% for Registered Indian men+ living on reserve. Similarly, this percentage ranged from 13.3% for Métis women+ to 31.4% for Registered Indian women+ living on reserve.

- The gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous men+ did not differ in a marked or consistent way from the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous women+. Both Registered Indian men+ and women+ living on reserve exhibited the largest gap with their non-Indigenous counterparts, with differences of 21.1 and 20.2 percentage points, respectively. Conversely, Métis men+ and women+ displayed the smallest gap in low-income situation with differences of 1.8 and 2.1 percentage points.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A2.6.

Measuring the gap

| 2015 | 2020 | Five-Year Change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Gap | Percentage | Gap | Percentage | Percentage change in gap | |

| Registered Indian on reserve | 47.7% | 33.9% | 31.3% | 20.6% | -16.4% | -39.2% |

| Registered Indian off reserve | 30.3% | 16.5% | 19.8% | 9.1% | -10.5% | -44.8% |

| Non-Status Indian | 25.2% | 11.4% | 16.8% | 6.1% | -8.4% | -46.5% |

| Inuit | 22.3% | 8.5% | 16.5% | 5.8% | -5.8% | -31.8% |

| Métis | 17.3% | 3.5% | 12.6% | 1.9% | -4.7% | -45.7% |

| Non-Indigenous | 13.8% | 10.7% | -3.1% | |||

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2016 to 2021 Census of Population. |

||||||

- Indigenous groups were more likely than the non-Indigenous population to be living in a low-income situation.

- The gap was especially large for Registered Indians living on reserve (20.6 percentage points higher than for the non-Indigenous population), although it had closed considerably since 2015, narrowing by 39.2%.

- Overall, there was a large narrowing of gap for each Indigenous group from 2015 to 2020, with the largest improvement among Non-Status Indians (46.5%), followed by Métis (45.7%), Registered Indians off reserve (44.8%) and Inuit (31.8%).

| Men+ | Women+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Percentage change in gap | Percentage | Percentage change in gap | |

| Registered Indian on reserve | -16.5% | -39.0% | -16.3% | -39.2% |

| Registered Indian off reserve | -10.0% | -45.8% | -10.9% | -43.7% |

| Non-Status Indian | -8.0% | -44.6% | -8.8% | -47.4% |

| Inuit | -6.0% | -33.3% | -5.7% | -30.0% |

| Métis | -4.1% | -37.9% | -5.2% | -47.5% |

| Non-Indigenous | -3.0% | -3.3% | ||

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2016 to 2021 Census of Population. Note: Given that the non-binary population is small, Statistics Canada produced a two-category gender variable that was applied to prevent disclosure of identifiable data for lower levels of geography when necessary. Consequently, information will be disseminated using the following categories: Men+, Women+. Individuals in the "non-binary persons" category are distributed in the other two gender categories and are denoted by the "+" symbol. |

||||

- The changes in gaps between Indigenous men+ and women+ compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts were mostly similar in terms of direction and strength.

- A large narrowing of the gaps was observed for both Indigenous men+ and Indigenous women+ compared to the non-Indigenous population.

- The full dataset for this table is available in Appendix A – Table A2.6.

Employment rate

The employment rate is another way to measure a population's economic health. This rate is the percentage of the working-age population (aged 25 to 64) that has a job. As seen in 2021, 538,415 Indigenous individuals aged 25 to 64 were employed, up 7.1% since 2016 (Table 6). For a full list of all data tables relevant to the employment rate, please see Appendix A, tables A3.1 to A3.6.

| 2016 | 2021 | Difference | Percentage Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered Indian on reserve | 69,235 | 66,880 | -2,355 | -3.4% |

| Registered Indian off reserve | 149,770 | 159,790 | 10,020 | 6.7% |

| Non-Status Indian | 68,565 | 85,290 | 16,725 | 24.4% |

| Inuit | 16,135 | 17,175 | 1,040 | 6.4% |

| Métis | 199,220 | 209,280 | 10,060 | 5.0% |

| Non-Indigenous | 13,764,415 | 13,847,435 | 83,020 | 0.6% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2016 to 2021 Census of Population. |

||||

Text alternative for Figure 15: Employment rate, 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47.1% | 58.7% | 64.8% | 55.2% | 69.1% | 74.1% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- Employment rates among Indigenous Peoples in 2021 were highest for Métis (69.1%) and lowest for Registered Indians on reserve (47.1%).

- Indigenous groups presented lower employment rates than the non-Indigenous population (74.1%), particularly Registered Indians living on reserve (a gap of 27.0 percentage points).

- Large gaps in employment rates were also found for Inuit (18.9 percentage points) and Registered Indians living off reserve (15.4 percentage points).

- By contrast, a smaller gap was observed for Non-Status Indians (9.3 percentage points). The smallest gap was found for Métis at 5.0 percentage points.

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A3.1.

Text alternative for Figure 16: Employment rate, 2001 to 2021, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 48.1% | 56.4% | 63.3% | 59.0% | 67.9% | 75.1% |

| 2006 | 50.2% | 61.8% | 67.4% | 59.7% | 71.5% | 76.3% |

| 2011 | 46.8% | 61.2% | 67.0% | 58.6% | 71.6% | 75.8% |

| 2016 | 46.9% | 60.2% | 66.1% | 57.4% | 70.4% | 76.0% |

| 2021 | 47.1% | 58.7% | 64.8% | 55.2% | 69.1% | 74.1% |

Source: Indigenous Services Canada. Custom Tabulations, 2021 Census of Population.

- Employment rates were relatively stable from 2001 to 2021, with each Indigenous group showing little overall change, although trends differed substantially across groups.

- Among Registered Indians on reserve, the employment rate decreased by 1.0 percentage points, from 48.1% in 2001 to 47.1% in 2021.

- Among Inuit, the drop in employment rate was slightly more pronounced at 3.8 percentage points, from 59.0% in 2001 to 55.2% in 2021.

- Over this period, Registered Indians living off reserve, Non-Status Indians and Métis saw small employment rate increases of 2.3, 1.5 and 1.2 percentage points, respectively, from 2001 to 2021.

- The gap in employment rates compared to the non-Indigenous population decreased for all Indigenous groups, with the exception of Registered Indians living on reserve and Inuit. While the gap for Registered Indians living on reserve fluctuated over the years, it was identical in 2001 and 2021 at 27.0 percentage points.

- By contrast, this gap increased for the Inuit population, from 16.1% in 2001 to 18.9% in 2021 (representing a widening of 2.8 percentage points).

- The full dataset for this figure is available in Appendix A – Table A3.2.

Text alternative for Figure 17: Employment rate, 2021, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25 to 64, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |