Evaluation of the Healthy Living Program

ISC Evaluation

September 28, 2022

PDF Version (918 Kb, 82 pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Healthy Living Program Overview

- 3.0 Evaluation Methodology

- 4.0 Key Findings: Relevance

- 5.0 Key Findings: Effectiveness

- 6.0 Key Findings: Efficiency

- 7.0 Key Findings: Sub-programs

- 8.0 Summary of Best Practices & Lessons Learned

- 9.0 Cross Cutting Themes

- 10.0 Conclusions

- 11.0 Recommendations

- Appendix A: Evaluation Issues and Questions

- Appendix B: Logic Model

- Appendix C: Logic Model Mapping

- Appendix D: Summaries of Sub-Programs

- Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative (ADI)

- Canada's Tobacco Strategy (CTS)

- Nutrition North Canada Nutrition Education Initiatives (NNCNEI)

List of Acronyms

- ADI

- Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative

- CBRT

- Community-Based Reporting Template

- CHP

- Community Health Plans

- CIRNAC

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

- CTS

- Canada's Tobacco Strategy

- FNIGC

- First Nations Information Governance Centre

- FNIHB

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

- FTCS

- Federal Tobacco Control Strategy

- HC

- Health Canada

- HL

- Healthy Living

- ISC

- Indigenous Services Canada

- KII

- Key Informant Interview

- MRAP

- Management Response and Action Plan

- NIDA

- National Indigenous Diabetes Association

- NNC

- Nutrition North Canada

- NNCNEI

- Nutrition North Canada Nutrition Education Initiatives

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- RHS

- Regional Health Survey

- SDOH

- Social Determinants of Health

- TB

- Treasury Board

Executive Summary

The overall purpose of the evaluation is to examine the Healthy Living Program (HL) and its constituent programs, as outlined in the Five Year Evaluation Plan at Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), and further to the Treasury Board (TB) Policy on Results.Footnote 1 The evaluation was undertaken to provide a neutral, evidence-based assessment on the following domains: relevance, effectiveness, and efficiency of the HL Program managed by the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, ISC (FNIHB-ISC). The program includes: the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative; Canada's Tobacco Strategy (formerly the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy – First Nations and Inuit Component);and Nutrition North Canada Nutrition Education Initiatives. The policy areas within the HL program: Nutrition, Chronic Disease Prevention, and Injury Prevention were not included in this evaluation. The evaluation also sought to highlight best practices, challenges, lessons learned, and recommendations to strengthen the HL Program and its sub-programs. It also presents findings in the context of climate change, service transfer, and early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the HL Program.

Background

The Healthy Living Program funds and supports culturally relevant community-based health promotion and disease prevention programs and services in First Nations and Inuit communities. Activities include promoting healthy behaviours and creating supportive environments in the areas of healthy eating, food security, physical activity, tobacco use, and chronic disease prevention, management and screening.

This evaluation focuses on the Healthy Living Program and its constituent programsFootnote 2, hereafter referred to as sub-programs:

- Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative (ADI) aims to reduce type 2 diabetes in First Nations and Inuit communities through health promotion and disease prevention programs, services and activities delivered by community diabetes workers and health service providers.

- Canada's Tobacco Strategy (CTS)Footnote 3 - The Federal Tobacco Control Strategy (FTCS) – First Nations and Inuit component was a knowledge development initiative that began in 2014-15 and continued through the timeframe of this evaluation. It supported the development and implementation of comprehensive, holistic, culturally appropriate tobacco control projects that were focused on reducing non-traditional tobacco use, while maintaining respect and recognition for traditional forms and uses of tobacco within communities.

- Nutrition North Canada (NNC) Nutrition Education Initiatives funded through ISC support culturally appropriate retail and community-based nutrition education activities in eligible isolated northern First Nations and Inuit communities. Activities focus on increasing knowledge of healthy eating and developing skills in the selection and preparation of healthy store-bought and traditional food.

Evaluation Scope and Methodology

This evaluation covers the period from Fiscal Year 2013-14 to 2018-19 further to the Treasury Board requirements and includes each of the three Healthy Living sub-programs managed by FNIHB-ISC. The evaluation was undertaken to provide a neutral and evidence-based assessment of relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, lessons learned, and best practices, for the following activities: Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative, Canada's Tobacco Strategy, and Nutrition North Canada Nutrition Education Initiatives. Moreover, although not part of the original scope, the evaluation also incorporated more recent data and actions taken by ISC to address additional factors impacting programming, especially in the context of service transfer, climate change, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The evaluation focused solely on First Nations communities. Due to a request by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami for a distinctions-based approach for conducting evaluations, the Inuit element of the Healthy Living Program will be evaluated at a date to be determined.

The evaluation was conducted in-house by the ISC Evaluation Directorate. It relied on a mixed-methods approachFootnote 4 that included the following lines of evidence: a document and literature review; 19 key informant interviews with FNIHB-ISC staff (including national and regional office staff); 1 key informant interview with non-ISC government staff; 9 key informant interviews with Indigenous partner organizations (Tribal Councils, First Nations Health Service Organizations, etc.); 1 key informant interview with a non-Indigenous partner organization; 2 key informant interviews with representatives from First Nation communities and; an online survey of 168 individuals working in/with First Nations communities.Footnote 5

As data collection occurred in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic with the resultant travel restrictions, direct site visits were not possible and were instead replaced by remote video/telephone interviews through various communication platforms.

Main Findings

Relevance:

The program remains relevant as the Regional Health Survey, conducted by the First Nations Information Governance Centre, reported that nearly three-fifths (59.8%) of First Nations adults reported having at least one known chronic health condition.Footnote 6 The federal government has a clear mandate to continue to address the greater risks and lower health outcomes associated with chronic diseases among First Nations individuals, families and communities. Budget 2018 laid out the renewal of the Tobacco Strategy, highlighted the significant gaps in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, and highlighted the higher diabetes prevalence rate faced by Indigenous peoples. Additionally, Budget 2016 allocated funds to expand NNC, to support all isolated northern communities.

Effectiveness:

One of the strengths of the Healthy Living Program lies in its design and delivery model being unique to each community, allowing for communities to define their own needs and priorities. As a result of the diversity that exists in programming across communities and in targeted activities, it is difficult to determine if the program is effectively reaching all community members in all regions it operates in. It was noted that in key informant interviews that although harder to reach groups were not excluded from programming, it was unclear if all or most communities are engaging in tailored strategies to specific demographics (working age population, 2SLGBTQIA+ peoples, or at-risk youth). A concern noted by key informant respondents regarding some harder to reach clientele, includes programming activities implemented during standard operating hours, making it difficult for the working age population to attend activities during the day.

The majority of key informant interview respondents did not feel there were particular groups being left out of programming, there was also limited description of strategies or targeted programming for harder to reach populations which may be due to the fact that key informant interview respondents were not involved in delivering programs directly at the community level.

The HL sub-programs, particularly the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative (ADI) and the NNC Nutrition Education Initiatives, complement each other well. Some survey respondents noted that since staff members were often responsible for multiple Healthy Living sub-programs there was inherently collaboration. There are many linkages with other government programs outside of Healthy Living (e.g., Non-Insured Health Benefits program) and with partner organizations. For example, across Federal government departments, the HL Program works with Health Canada for Canada's Tobacco Strategy and with Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) for Nutrition North Canada. The FNIHB National Office works and collaborates with both the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) to inform the Healthy Living program.

However, a consistent challenge faced by the evaluators was the lack of available and adequate data to properly assess the achievement of the program's progress towards immediate and intermediate outcomes. With the program requiring less detailed reporting from communities as a result of diverse funding agreements, there is often an absence of specific and robust program performance data to effectively speak to the program's stated outcomes. Evaluations can help to fill this void by collecting additional data, both qualitative and quantitative, as feasible. Part of the challenge for this evaluation was due to the fact that the evaluation was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This directly impacted the evaluation's team ability to conduct site visits and engage communities in a more fulsome manner.

Efficiency:

The most consistently reported challenge from partners and ISC national and regional staff across all sub-programs is a lack of funding particularly in the human resource areas. Funding constraints have a negative impact on recruiting and retaining the right community-level talent, and access to professional development training opportunities are limited. Funding has been stagnant (i.e., not keeping up with inflationary pressures, and the increased needs of the Program) for many years, leading to unmet needs of the program and little to no increase in salaries at the community levels, contributing to high turnover rates, and vacant positions.

Collection of data on indicators for the HL Program is primarily the responsibility of individual communities under the FNIHB funding agreements between FNIHB and individual communities. However, while some communities report on health-related indicators, not all communities do report, or report to the full extent. Throughout interviews, key informants expressed the importance of collecting and utilizing the community-based reporting template (CBRT)Footnote 7 to not only fulfil funding requirements, but also to provide a snapshot of the community's health and well-being in order to tailor community health priorities. There is also an expressed need from partner organizations to further improve the CBRT, as it does not collect information at a sufficiently detailed level for communities to effectively track performance and achievement of results.

Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative:

Since the 2014 Evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Healthy Living and Healthy Child Development programs, this evaluation has found that overall, considerable progress has been made to suggest that the ADI has delivered meaningful results in community-based health promotion and primary prevention. However, according to the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC), "nearly three-fifths (59.8%) of First Nations adults, one-third (33.2%) of First Nations youth, and more than one-quarter (28.5%) of First Nations children have reported having one or more chronic health conditions. Among First Nations children, the number of reported conditions shows a significant decrease from the Regional Health Survey (RHS) Phase 2 (2008/10)."Footnote 8 Of note is that diabetes continues to remain to be the most noted chronic health condition reported by the FNIGC among First Nations adults.

Strong efforts were also made by communities to bring attention to traditional physical activities and reducing sedentary time, which can prevent and/or reduce chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes. However, there exists varying gaps in the level of screening and management effectiveness across regions.

Key informant interview respondents noted that communities lack proper screening tools, such as access to specimen collection and lab licensure, as well as access to provincial health data.Footnote 9 As well, current capacity building and training efforts are on-going for staff supporting the ADI. Specifically, both key informant interview respondents and survey respondents are interested in building their own capacity to better support clients and families with managing and improving their mental health. They are both also interested in having access to training that goes beyond the biomedical component of type 2 diabetes. The engagement of regional partners at their respective regional community of practice groups, which key informant interview respondents have referred to as "working groups" has been successful.

The evaluation notes a few key challenges that may hinder the ADI from potentially meeting needs and priorities, including the impact of funding constraints, staffing challenges, technological disadvantages faced by some clients, and the impact of food insecurity.

Canada's Tobacco Strategy:

As of 2017-18, under the FTCS, 56% of First Nations and Inuit communities had access to tobacco control activities.Footnote 10 A number of successes were demonstrated, for example: a doubling in the number of indoor and outdoor smoke-free spaces in communities; 173 new smoking-related resolutions passed at the local level; increased participation of community members in smoking cessation programs/interventions, with the overall smoking cessation rate surpassing estimated cessation rate among other segments of the general Canadian population.Footnote 11

The survey indicated that 53% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that Canada's Tobacco Strategy was operating effectively to reduce commercial tobacco use. Through key informant interviews, cessation efforts were identified as being a major challenge. Survey respondents also noted major challenges in retaining staff, promoting community engagement, and engaging individuals before they begin smoking. In addition, given the important cultural and spiritual roots of tobacco in many First Nations practices, tobacco cessation research has shown that culturally appropriate interventions bolster the effectiveness of Indigenous tobacco programming.

Nutrition North Canada (NNC) Nutrition Education Initiatives:

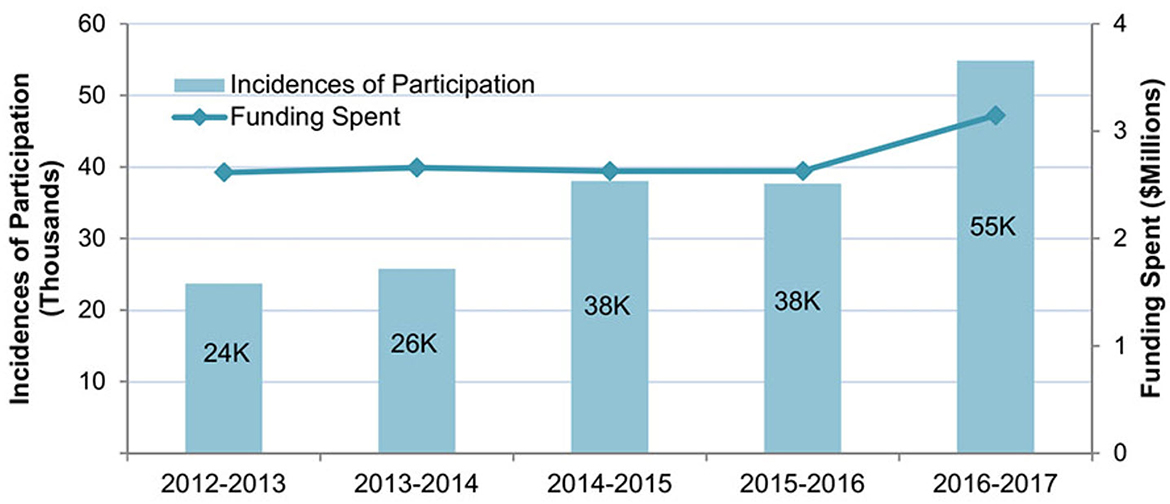

The recent Horizontal Evaluation of NNC found that nutrition education initiatives funded through FNIHB were a key successFootnote 12. The growth in participation in community-based nutrition education initiatives demonstrates that more people are acquiring knowledge and skills to eat healthy. The evaluation also found that there is a higher demand for certain types of activities such as traditional food knowledge and skills, as well as retail-based nutrition knowledge and awareness.

Many key informant interview respondents and survey respondents expressed concerns around the eligibility for Nutrition Education Initiatives. Funding is currently dependent on the First Nations community meeting eligibility criteria for the NNC subsidy administered by CIRNAC. While the nutrition education initiatives function as a component of Nutrition North Canada, key informant interview respondents expressed that nutrition education remains relevant for all communities and expressed that the current eligibility criteria does not meet the needs of many communities. Survey and key informant interview respondents also expressed concerns about inadequacy in funding for Nutrition Education Initiatives given the high prices of food in the north and the travel expenses for community health workers that service multiple communities.

Climate Change:

The effects of climate change on the HL Program are potentially significant, especially in the context of remote and isolated communities. There are two elements to consider in terms of climate change effects as they related to the Healthy Living Programs: impacts on the food supply chain, and changes in the availability of traditional or country foods as a result of changes to the environment and ecosystems (e.g., animal migration pattern changes, temperatures changes, extreme weather conditions such as fires and floods). Both of these elements have the potential to impact the availability of nutritious foods that are important elements of the ADI and NNC Nutrition Education Initiatives, as well as food security itself in remote, isolated and northern communities.

Climate change has an impact on food security, and as a result can impact the HL Program. Many community-based activities supported through HL sub-programs seek to improve access to and availability of nutritious food, for example by incorporating healthy store bought and traditional foods, and supporting gardening activities. Survey respondents and key informant interview respondents noted that climate change is causing a less reliable food supply chain, as once reliable ice roads used for transport of foodstuffs are increasingly impassable or are in operation for a shorter period of time due to late freeze-up/ early melting. Additionally, changes in animal migration patterns, extreme weather conditions and temperature changes have had an impact on the local availability of plants and animals therefore increasing food security challenges.

Service Transfer:

Many communities across all regions are incrementally moving towards flexible funding arrangements and while this is a positive step in the service transfer continuum, there remain hurdles to transferring financial responsibilities to communities directly. Most significantly, key informant interview respondents cited that the role that ISC provides in terms of financial oversight (i.e., management tools, databases, etc.) is not yet being transferred to community health directors and staff, which is an important administrative aspect of service transfer. This factor impedes the ability of ISC regional offices to adapt to changing community need-based priorities.

Best Practices:

The evaluation presents several best practices that were highlighted by ISC key informant interview respondents both at national and regional offices. Of the list of best practices presented in the evaluation, these initiatives stood out: the inclusion of traditional tobacco practices and land-based activities; the establishment of intra-regional ADI working groups, regional-specific; and various best practices such as regional diabetes coordinators and food security coordinators. As well, the evaluation compiled general guiding principles as shared by key informant interview respondents with regards to lessons learned in community programming design.

Early Impacts of COVID-19:

Although not within the original scope, the evaluation investigated the early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Healthy Living Program. COVID-19 health restrictions heavily impacted the undertaking of this evaluation. In particular, the resultant travel-restrictions affected the evaluation team's inability to conduct site visits and directly interview end-users. As well, the availability of respondents (both survey respondents and key informant interviews) was another limiting factor. This is important contextual information to better understand how the program has evolved to address the challenges and stresses brought upon by COVID-19. All evaluations conducted during the timeframe of March 2020-2021, have included early impacts of COVID-19 on programming. Future evaluations will endeavour to look at the full breadth of Covid-19 impact. Key informant interview respondents addressed the following themes in the context of COVID-19: effects on planned Healthy Living activities; challenges relating to the sub-programs; and any unintended impacts as a consequence of ISC's COVID-19 pandemic response. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Healthy Living program, and associated sub-programs, have been notable. COVID-19 brought several challenges to HL Program delivery, including pivoting activities to online platforms. While this has caused access and participation challenges for some community members, it has also allowed for various clients who would not otherwise attend targeted activities to participate in online activities.

Recommendations:

Based on the findings of this evaluation report, it is recommendedFootnote 13 that ISC:

- Work with the ISC Chief Data Officer (CDO), ISC Chief Information Officer (CIO) and the ISC Director General responsible for Performance Measurement to liaise with First Nations partners to support the development of a data strategy to improve the availability of Healthy Living performance data at the community, regional and national levels. Options should take in to consideration (but not be limited to): Indigenous data sovereignty; data sharing mechanisms; data standardization; reducing reporting burdens; Gender Based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus); and gradual service transfer.

- ISC to work with First Nations and health systems partners to explore potential mechanisms for increased, sustainable funding to better support community capacity in the design and delivery of Healthy Living programming based on the unique needs and priorities of communities, taking into consideration remoteness and gradual service transfer.

- Support First Nations and health systems partners to continue incorporating Indigenous-led principles or a potential framework that highlights and integrates traditional practices and teachings into the Healthy Living program.

- Building on best practices, explore opportunities to support the sharing of information among Healthy Living workers and across sub-programs, as a way to continually improve efficiencies and identify common needs and best practices at the regional and community level.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Healthy Living Program

1. Management Response

Indigenous Services Canada, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (ISC-FNIHB) acknowledges and concurs and/or partially concurs with the recommendations outlined in the report of the evaluation of the Healthy Living Program conducted by Indigenous Services Canada's Evaluation Directorate.

For all recommendations, ISC-FNIHB recognizes the importance of committed and dedicated action towards self-determination of Indigenous Peoples and towards service transfer. ISC-FNIHB is supporting First Nations to influence, manage and increase control over health programs and services that affect them and improve access to quality health services. While supporting these shifts, ISC-FNIHB continues to work with First Nations partners and communities in advancing their priorities, for example, supporting training and capacity building efforts in regions, and facilitating access or linkages to healthy living services, supports and resources (e.g., nutrition, food security). We will work with partners to examine options for sustainability of funding, incorporating traditional practices and knowledge transfer of best practices. ISC-FNIHB is committed to actively participating in discussions with First Nations partners, including the Assembly of First Nations, to determine where we go from here as a collective to address these issues.

ISC-FNIHB recognizes that persistent data gaps undermine overall health and wellness as well as effective service delivery across the Department. Data challenges exist within the program and this is a broader challenge across the sector. Addressing data challenges is a cross-cutting, interconnected issue and is a priority of the whole Department. Therefore, ISC-FNIHB partially agrees with Recommendation 1 as an individual program only holds some of the levers towards implementing this recommendation. We will undertake incremental work in the development of a data strategy outlined in Recommendation 1, to improve the availability of Healthy Living performance data at the community, regional and national levels. We will direct our efforts to undertake a gaps analysis and update the data collection instruments for Healthy Living aligning to the Departmental Results Framework. We will work within current Departmental efforts to ensure a cohesive and unified approach to First Nation data across all ISC sectors. This approach aligns with ISC's current mandate, which is predicated on the understanding that Indigenous control leads to better outcomes for Indigenous Peoples, and data is no exception.

It is important to note that this evaluation covers the period from Fiscal Year 2013-14 to 2018-19. As data collection occurred in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic with the resultant travel restrictions, direct site visits were instead replaced by remote video/telephone interviews through various communication platforms using a mixed-method approach. The Department recognizes that this evaluation was undertaken during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many Healthy Living programs and services were reduced or paused, and funding recipients/communities diverted resources to help address critical pandemic-related needs. Ultimately, the timing of the evaluation process significantly limited participation in this evaluation, especially at the community level. As regular programming and services begin to ramp up, ISC-FNIHB will build on what was heard during the evaluation by working with its First Nations partners and communities to identify needs and supports required to resume and strengthen programming.

The evaluation report identifies several cross-cutting topics such as service transfer and performance measurement, which implicate not only the Healthy Living Program but the Department as a whole. With this in mind, the Action Plan is focused on collaboration with First Nations partners, ISC sectors and other federal departments.

ISC-FNIHB intends to initiate implementation of the recommendations immediately. An annual review of the Management Response and Action Plan will be conducted by

ISC Evaluation and shared with the ISC Performance Management and Evaluation Committee (PMEC) to monitor progress and activities.

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work with the ISC Chief Data Officer (CDO), ISC Chief Information Officer (CIO) and the ISC Director General responsible for Performance Measurement to liaise with First Nations partners to support the development of a data strategy to improve the availability of Healthy Living performance data at the community, regional and national levels. Options should take in to consideration (but not be limited to): Indigenous data sovereignty; data sharing mechanisms; data standardization; reducing reporting burdens; Gender Based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus); and gradual service transfer. | We __partially__ concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Dr. Tom Wong, Chief Medical Officer and Director General, Office of Population and Public Health (OPPH), First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) Robin Buckland, Chief Nursing Officer, Director General, Office of Primary Health Care, FNIHB, ISC |

Start Date: October 2022 |

|

| ISC-FNIHB partially concurs with this recommendation as this is a sector-wide issue and aligns with broader Departmental efforts to transform the existing approach to Indigenous data across all sectors (e.g., health, education, child and family services). ISC-FNIHB will

Action 1.1: Undertake scoping and gaps analysis of data used for Healthy Living Program. (Q1 2023-24) Action 1.2: Engage Indigenous expert(s) to advise on indicators for Healthy Living related outcomes. (Q2 2023-24) Action 1.3: Develop Options for updating Healthy Living indicators and Data Collection Instruments. (Q3 2023-24) Action 1.4: Update Performance Information Profiles and Data Collection Instruments for Healthy Living. (Q4 2023-24) |

Completion: March 31, 2024

|

Status: As of: (September 16, 2022) |

||

| 2. ISC to work with First Nations and health systems partners to explore potential mechanisms for increased, sustainable funding to better support community capacity in the design and delivery of Healthy Living programming based on the unique needs and priorities of communities, taking into consideration remoteness and gradual service transfer. | We __do___ concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Dr. Tom Wong, Chief Medical Officer and Director General, Office of Population and Public Health (OPPH), First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) Robin Buckland, Chief Nursing Officer, Director General, Office of Primary Health Care, FNIHB, ISC |

Start Date: |

|

To support this recommendation, the Healthy Living Program will:

|

Completion:

|

Status: As of: (Insert Update Here) |

||

| 3. Support First Nations and health systems partners to continue incorporating Indigenous-led principles or a potential framework that highlights and integrates traditional practices and teachings into the Healthy Living program. | We __do___ concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Dr. Tom Wong, Chief Medical Officer and Director General, Office of Population and Public Health (OPPH), First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) | Start Date: October 2022 |

|

To support this recommendation, the Healthy Living Program will:

|

Completion:

|

Status: As of: (Insert Update Here) |

||

| 4. Building on best practices, explore opportunities to support the sharing of information among Healthy Living workers and across sub-programs, as a way to continually improve efficiencies and identify common needs and best practices at the regional and community level. | We __do__ concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Dr. Tom Wong, Chief Medical Officer and Director General, Office of Population and Public Health (OPPH), First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) | Start Date: October 2022 |

|

To support this recommendation, the Healthy Living Program will:

|

Completion:

|

Status: As of: (Insert Update Here) |

1.0 Introduction

The overall purpose of the evaluation was to examine the Healthy Living Program and its constituent sub-programs, as outlined in the Five Year Evaluation Plan of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), further to the Treasury Board (TB) of Canada Policy on Results. The evaluation focused on the following three sub-programs of the Healthy Living Program suite: Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative (ADI), Canada's Tobacco Strategy (CTS) (formerly the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy – First Nations and Inuit Component), and Nutrition North Canada (NNC) Nutrition Education Initiatives. The Healthy Living Program and its sub-programs are supported and delivered through the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) within ISC.Footnote 14 The evaluation covers the fiscal years 2013-14 through 2018-19, but also includes program activities undertaken from April 2019 up to and including fiscal year 2019-20.Footnote 15 The total funding allocated to the HL Program (including sub-programs and policy areas) from 2013-14 to 2018-19 was approximately $426 million.

2.0 Healthy Living Program Overview

2.1 Program Description

The Healthy Living Program funds and supports culturally relevant community-based health promotion and disease prevention programs and services in First Nations and Inuit communities. Activities include promoting healthy behaviours and creating supportive environments in the areas of healthy eating, food security, physical activity, tobacco, and chronic disease prevention, management and screening. The Healthy Living Program evaluation focuses on the three sub-programs:Footnote 16 ADI, CTS, and NNC Nutrition Education Initiatives. The policy areas within Healthy Living of Nutrition, Chronic Disease Prevention and Injury Prevention were not included in the evaluation.

Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative (ADI)

The ADI aims to reduce the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in First Nations and Inuit communities. ADI funding supports community-led health promotion and disease prevention programming, services and activities delivered by community workers and health service providers. During the time frame of this evaluation, ADI was the only sub-program within the Healthy Living Program funded universally, with all communities having access to ADI funding. The program consists of four components:

- Community-based health promotion and primary prevention;

- Screening and management;

- Capacity building and training; and,

- Knowledge mobilization.

The ADI program activities offered in each community vary based on local needs, priorities and capacity.

Canada's Tobacco Strategy (CTS)Footnote 17

The First Nations and Inuit component of the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy (FTCS) was a project-based knowledge development initiative that began in 2014-15 and continued through the timeframe of this evaluation. The FTCS provided proposal-based funding that supported the implementation of 16 projects and 3 strategies, reaching approximately 56% of First Nations and Inuit communities. The FTCS supported the development and implementation of comprehensive, holistic, culturally appropriate tobacco control projects that focused on reducing commercial tobacco use, while maintaining respect and recognition for traditional forms and ceremonial uses of tobacco within First Nation communities. The FTCS was guided by the World Health Organization's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, and included a comprehensive approach to tobacco control, organized around 6 essential intervention elements, which included: 1) protection; 2) reducing access to tobacco products; 3) prevention; 4) education; 5) cessation, and; 6) research and evaluation.

The projects actively participated in a community of practice, a forum to share knowledge, lessons learned, successes/promising practices towards the reduction of commercial tobacco.

A case study with early findings of the First Nations and Inuit Component of the FTCS (from 2014-15 and 2015-16) was included in the evaluation of the FTCS horizontal initiative that was completed by the Office of Audit and Evaluation of Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada in 2017Footnote 18.

The FTCS was renewed in 2018 and renamed Canada's Tobacco Strategy (CTS). CTS is a Health Canada-led comprehensive strategy to help Canadians who smoke to quit or reduce the harms of their addiction to nicotine and protect the health of young people and non-smokers from the dangers of tobacco use. The main themes of the renewed CTS are:

- Help Canadians quit tobacco;

- Protect youth and non-tobacco users from nicotine addiction;

- Support Indigenous-led approaches towards reducing commercial tobacco use; and

- Strengthen science, surveillance and partnerships.

Through CTS, ISC provides funding to support Indigenous communities across Canada for the development and implementation of distinct First Nations, Inuit, and Métis approaches to reduce commercial tobacco use. This approach supports self-determination of First Nations, Inuit and the Métis peoples to identify needs and priorities of individuals, families, communities, and supports Indigenous control over culturally appropriate service design and delivery.

Although the evaluation period coincided with the previous FTCS, it will be referred to as the renamed CTS throughout the remainder of the report acknowledging that key differences exist between the strategies in terms of funding distribution and approach.

Nutrition North Canada Nutrition Education Initiatives

Nutrition North Canada is a Government of Canada program that helps make nutritious food and some essential items in isolated eligible northern communities through a retail subsidy and a Harvester's Support Grant delivered through, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC), and through NNC Nutrition Education Initiatives supported by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

NNC Nutrition Education Initiatives are funded through ISC to support culturally appropriate retail and community-based nutrition education activities in eligible isolated northern First Nations and Inuit communities. Activities focus on increasing knowledge of healthy eating and developing skills in the selection and preparation of healthy store-bought and traditional or country foods. Communities decide which activities to undertake based on their local needs and priorities. NNC Nutrition Education Initiatives were included in the scope of the Horizontal Evaluation of NNC for the fiscal years 2012-13 to 2017-18, published in 2020Footnote 19.

At ISC, FNIHB is responsible to provide the NNC Nutrition Education Initiatives funding and support through the Healthy Living Program to all the First Nations and Inuit communities eligible for the program.

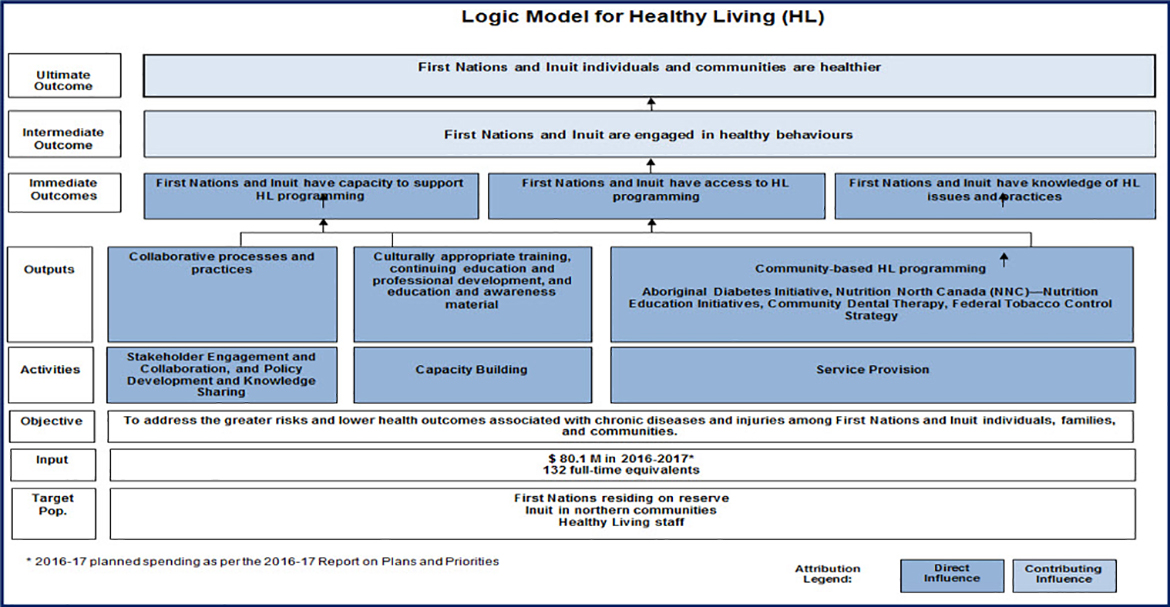

2.2 Program Objectives and Expected Outcomes

The objective of the Healthy Living Program is to address the greater risks and lower health outcomes associated with chronic diseases and injuries among First Nations and Inuit individuals, families, and communities.The following outlines the immediate, intermediate, and ultimate outcomes and objectives of the program, according to the program's logic model:

Immediate Outcomes

- First Nations and Inuit have capacity to support Healthy Living programming.

- First Nations and Inuit have access to Healthy Living programming.

- First Nations and Inuit have knowledge of Healthy Living issues and practices.

Intermediate Outcomes

- First Nations and Inuit are engaged in healthy behaviours.

Ultimate Outcome

- First Nations and Inuit Individuals and communities are healthier.

The logic model for the Healthy Living Program can be found in Appendix B.

In addition, the Healthy Living Program is in alignment with the following Calls to Action released by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in June 2015Footnote 20:

Call to Action #18: We call upon the federal, provincial, territorial, and Aboriginal governments to acknowledge that the current state of Aboriginal health in Canada is a direct result of previous Canadian government policies, including residential schools, and to recognize and implement the health-care rights of Aboriginal people as identified in international law, constitutional law, and under the Treaties.

Call to Action #19: We call upon the federal government, in consultation with Aboriginal peoples, to establish measurable goals to identify and close the gaps in health outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities, and to publish annual progress reports and assess long-term trends. Such efforts would focus on indicators such as: infant mortality, maternal health, suicide, mental health, addictions, life expectancy, birth rates, infant and child health issues, chronic diseases, illness and injury incidence, and the availability of appropriate health services.

Call to Action #20: In order to address the jurisdictional disputes concerning Aboriginal people who do not reside on reserves, we call upon the federal government to recognize, respect, and address the distinct health needs of the Métis, Inuit, and off-reserve Aboriginal peoples.

2.3 Program Management and Key Partners

Program Management

FNIHB staff at the National Office within the National Capital Region lead strategic, program policy development and planning in support of the Healthy Living program, working with FNIHB regional offices and First Nations and Inuit partners at the national level (i.e., National Indigenous Organizations). The core responsibilities of the National Office include: program framework design; the national program funding allocations for sub-programs; national program monitoring; data collection and analysis; reporting and evaluation; provision of advice and/or guidance on program delivery; and working with FNIHB Regions and First Nations and Inuit partners to identify and address gaps in Healthy Living programming and services. The National Office may also issue and manage funding arrangements for national partners and stakeholders.

The FNIHB regional offices play a lead role in supporting communities with program delivery by working with First Nations and Inuit partners at the regional and local levels. The regional offices are also responsible for the management of funding arrangements, program performance monitoring, and information roll-ups. With the exception of the Northern Region, regions also support communities with program delivery when needed or requested by funding recipients or communities. There is a wide variation in how each region operates relating to the Healthy Living program. Consequently, the information collected from the regions for this evaluation varied and may not necessarily be comparable from one region to another.

The FNIHB Northern Region works directly with the territorial governments and self-governing First Nations in Yukon and selected communities within Northwest Territories. In Nunavut and the remainder of Northwest Territories, the FNIHB Northern Region works directly with territorial governments to negotiate funding arrangements for health programming, and ensures that First Nations partners are engaged in decision-making. Each territory is responsible to administer the funds to communities and organizations such as First Nations band councils, health authorities, Inuit associations, and voluntary and non-profit organizations. Programming is targeted to the entire population in each territory, not only First Nations. As such, the Healthy Living Program in the North has unique reporting templates used to gather performance measurement information that will be used to support evaluation efforts where applicable.

The communities, Tribal Councils or other Indigenous health organizations are funded through funding arrangements to support the implementation and delivery of the Healthy Living Program. Community or Tribal Council implementation and support is unique and based on the needs, and priorities of the communities or tribal councils/organizations and often includes implementing a variety of healthy living activities, building internal capacity through the hiring, managing and training of community program staff, providing office space and program tools and resources, and working collaboratively with other programs and partners.

Program Partners

First Nations communities are diverse in terms of culture, language, geographical location, population size, health needs, priorities, level of funding from FNIHB, access to provincial health services, and their capacity to manage their own services. As such, communities or Tribal Councils may modify programming to address these factors in order to better meet their specific health priorities and needs. The variations in programming may influence what data is collected as well as the potential impact of the programs and services.

To support program and service delivery, the Healthy Living Program collaborates with a number of other partners and stakeholders. For example, the Healthy Living Program works with:

- Indigenous partners and organizations at national and regional levels; and

- Other FNIHB program and service areas such as Healthy Children, Youth and Families and Mental Wellness; and

- Other federal departments such as Health Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

FNIHB's Senior Management Committee is the main decision-making forum for the Branch on issues related to policy development and priority setting. It includes representation from senior management at national office and regional offices and representatives from the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and Inuit Tapiritiit Kanatami (ITK).

3.0 Evaluation Methodology

3.1 Scope and Evaluation Issues

This evaluation covers the period from Fiscal Year 2013-14 to 2018-19 further to the Treasury Board requirements and includes each of the three Healthy Living sub-programs managed by FNIHB-ISC. The evaluation was undertaken to provide a neutral and evidence-based assessment of relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of the Healthy Living Program, including, Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative, Canada's Tobacco Strategy (formerly the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy – First Nations and Inuit Component), and Nutrition North Canada Nutrition Education Initiatives. The evaluation also sought to highlight best practices, challenges, lessons learned and recommendations to strengthen the Healthy Living Program and its sub-programs. The policy areas within Healthy Living of Nutrition, Chronic Disease Prevention and Injury Prevention were not included in this evaluation. Moreover, although not part of the original scope, the evaluation also incorporates more recent data and actions taken by ISC to address additional factors impacting programming, especially in the context of service transfer, climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The evaluation focused solely on First Nations communities. Due to a request by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami for a distinctions-based approach for conducting evaluations, the Inuit element of the Healthy Living Program will be evaluated at a date to be determined. Additionally, as responsibilities for federal health programs have been transferred to the First Nations Health Authority through the British Columbia Tripartite Framework Agreement on First Nation Health Governance, British Columbia does not fall within the scope of the evaluation.

The evaluation was conducted through the lenses of Gender Based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus) and the federal commitment to Truth and Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. The evaluation includes the above Healthy Living activities and initiatives undertaken in all jurisdictions across Canada, with the exception of British Columbia, and to a limited extent in the North, as outlined above.

3.2 Evaluation Design and Methods

The evaluation was conducted in-house by the ISC Evaluation Directorate. It relied on a mixed-methods approach that included the following lines of evidence:

- A document and literature review;

- Key Informant Interviews:

- 19 key informant interviews with FNIHB-ISC staff (including national and regional office staff);

- 1 key informant interview with non-ISC government staff;

- 9 key informant interviews with Indigenous partner organizations (Tribal Councils, First Nations Health Service Organizations, etc.);

- 1 key informant interview with a non-Indigenous partner organization;

- 2 key informant interviews with representatives from First Nation communities; and;

- Online Survey:

- an online survey of 168 individuals working in/with First Nations communities. Of the survey respondents who responded to the question on what their role was in the Healthy Living Program, 80% identified themselves as the following, in descending order of frequency: community health workers, health directors/managers, dietitians/nutritionists, and nurses. A variety of roles were mentioned by the remaining 20%, including mental wellness workers, social workers and a range of other roles, with each being mentioned by only one individual.)

As data collection occurred in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic with the resultant travel restrictions, direct site visits were not possible and were instead replaced by remote video/telephone interviews through various communication platforms. The pandemic also directly impacted the evaluators' ability to interview community partners. Given that many community partners were involved in the response to COVID-19, the evaluators were unable to fully engage them as planned. However, partner responses were given heavy weight when reporting results.

3.3 Limitations

Table 1 below outlines the limitations encountered during the implementation of the selected methods for this evaluation and the corresponding mitigation strategies that the evaluation team utilized to ensure that the evaluation findings are reliable and have been validated.

| Limitation | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|

| An important limitation of this evaluation is that the program performance data only partially provides outcome level data and reporting requirements vary across communities. As a result, there is a lack of available comprehensive and consistent program performance data at the immediate and intermediate levels. In addition, there is a lack of data that would allow for the monitoring and analysis of GBA Plus. | The evaluation sought to collect primary data as best it could, given the significant data collection constraints during the COVID-19 emergency response. Where possible, the evaluators also utilized available secondary data. Evaluations rely heavily on program performance data as a foundational source of evidence to assess program effectiveness. Evaluations triangulate performance data with other primary and secondary sources of qualitative and quantitative data to formulate objective, fact-based findings and recommendations. |

| The COVID-19 pandemic prevented travel to communities, and subsequently there was limited ability to conduct site visits to both regions and communities. This resulted in an inability to collect data from end-users/clients of HL programming, which in turn resulted in the use of secondary data, for example the Regional Health Survey, which provides a holistic picture of program results, but it is not specifically focussed on the HL program. | The evaluation team conducted virtual interviews with key informants at several different levels of the program: national office, regional office and at the community level where sub-programs are implemented. As well, the evaluation team distributed an electronic survey which received responses from all regions involved in the HL Program across Canada. |

| As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were fewer responses in key informant interviews and the online survey from respondents that were supporting the CTS and NNC sub-programs. | Additional secondary data was utilized to complement survey responses and provide further analysis. |

| This evaluation took place during the transition from projects under the previous project based FTCS – First Nations and Inuit Component to the current CTS with funding integrated with other Healthy Living funding and which also has coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. | The evaluation acknowledges that the First Nations and Inuit component of the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy was a knowledge development initiative that began in 2014-15 under the FTCS and continued through the timeframe of this evaluation in 2018-19. Thus, given the transition, the scope of this evaluation does not capture the renewed CTS, announced in Budget 2018. |

| Owing either to the COVID-19 pandemic or for other reasons including perhaps a stronger ADI presence in communities, there was limited online survey engagement from First Nations communities supporting the CTS and NNC.Footnote 21 | ISC national and regional offices were included as units of analysis to provide further analysis where there was limited CTS and NNC survey engagement. |

3.4 Indigenous Engagement

The evaluation employed FNIHB-ISC's engagement protocol, which calls for National Indigenous Organizations (in this case, the Assembly of First Nations) to review evaluation documentation at various stages of the process (methodology report, preliminary findings, and draft evaluation report) and comment/provide suggestions on the evaluation methodology, questions to be asked to help promote culturally appropriate evaluations for FNIHB programs. Additionally, regional Indigenous partners (e.g. health partnership tables, tribal councils) were engaged by FNIHB-ISC regional offices on a less-formal basis to provide supplementary input on community selection and evaluation methodology, which was then shared with the evaluation team.

3.5 Organization of the Findings

While this evaluation viewed the Healthy Living Program as a holistic entity, the key focus was, to a greater extent, on the performance of each of the three individual sub-programs, as there is little overlap amongst them from a management and operational perspective. For example, ADI is universally funded, whereas the NNC Nutrition Education Initiatives target eligible isolated northern communities. Also in contrast, with the transition from the FTCS to CTS, there was a switch from project-based funding to on-going funding. Of note is that a greater number of survey respondents acknowledged being involved with ADI than with either the CTS or NNC Nutrition Education Initiatives. As such, many of the evaluation's findings are sub-program-specific, as opposed to program-wide. Findings 1-11 may be considered to cross-cut two or more Healthy Living sub-programs, while the remainder are specific to each of the three sub-programs.

4.0 Key Findings: Relevance

4.1 Program Relevance

Finding 1: The Healthy Living Program remains relevant. Current and ongoing health issues contributing to the need for the Healthy Living Program include: deep rooted health inequities faced by First Nation communities and the impact of the social determinants of health on programming.

The Healthy Living Program continues to remain relevant as the Regional Health SurveyFootnote 22 conducted by the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC), reported that "nearly three-fifths (59.8%) of First Nations adults, one-third (33.2%) of First Nations youth, and more than one-quarter (28.5%) of First Nations children have reported having one or more chronic health conditions. Among First Nations children, the number of reported conditions shows a significant decrease from the RHS Phase 2 (2008/10)."Footnote 23 Of note is that diabetes continues to remain to be the most noted chronic health condition reported by the FNIGC among First Nations adults.

In July 2018, Diabetes Canada released their Diabetes 360 Report: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for CanadaFootnote 24, highlighting the significant health-crisis impacting close to 11 million Canadians that are living with prediabetes or diabetes. The Report states that, "for First Nations peoples, the risk of being diagnosed with diabetes is up to 80% and in some subgroups within this population, it is even higher."Footnote 25 For example, diabetes prevalence is 3-5 times greater for First Nations peoples living on-reserve, than non-First Nations Canadians. In addition, the rates of complications from diabetes are also higher for First Nations on-reserve than non-First Nations Canadians.Footnote 26 In contrast to the general Canadian population (in which the prevalence is predominately higher in men than women), First Nations women bear a heavier diabetes burden than First Nations men, across most age groups. In fact, Indigenous individuals that are diagnosed at an increasingly younger age, have greater severity at diagnosis, and experience poorer treatment outcomes in comparison to the general Canadian population."Footnote 27

Prevalence of smoking amongst First Nations adults also remains relatively high, with the Regional Health Survey Phase 3 reporting that more than half (53.5%) of First Nations adults smoked cigarettes, with 40% saying they smoked on a daily basis.Footnote 28 Phase 2 of the Regional Health Survey reported that 56.9% of First Nations adults smoked cigarettes.Footnote 29 While this presents a small decrease in use, the three phases of the Regional Health Survey reported relatively stable prevalence of smoking in First Nations adults.Footnote 30 Comparatively, 14.8% of the general Canadian population smoke.Footnote 31

In addition to the high prevalence rates of diabetes and smoking, three factors that contribute to the disproportionate health inequities in First Nations communities are notable. First, health inequities are deeply rooted in the historical relationship between First Nations communities and the health systems. In particular, the impacts of colonization have resulted in "a legacy of environmental dispossession, degradation of the land, substandard living conditions, inadequate access to health services, social exclusion and a dislocation from community, language, land and culture. These policies have been clearly linked to adverse health consequences for individuals and community."Footnote 32

Second, the complex, inter-related nature of social determinants of health contributes to the serious health challenges that many First Nations communities continue to face. The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) recognizes that health is determined by the complex inter-related nature of social determinants of health between social and economic factors, the physical environment and individual behaviour. PHAC has identified twelve social determinants of health: gender, culture, health services, income/social status, social support networks, education/literacy, employment and working conditions, social environments, physical environments, personal health practices and coping skills, healthy child development, and biology/genetic endowmentFootnote 33. In fact, 70% of online survey respondents either agreed or strongly agreed, that the Healthy Living sub-programs paid appropriate attention to integrating various social determinants of health, such as income, education level, and the physical environment Examples of this include: the HL Program taking into consideration different income levels when recommending healthy food purchases to clients, introducing targeted education activities to various age groups (elementary students, high school students etc.) and recommending physical activities that are available to those individuals living on-reserve.

Lastly, the inequitable distribution of economic resources combined with other social determinants of health has further contributed to food insecurity challenges faced by First Nations communities. Food insecurity challenges can be linked to the inadequate intakes of several nutrients, likely contributing to the disproportionate health inequities faced by First Nations communities. The First Nations Food Nutrition and Environment Study (2008-2018)Footnote 34, found that, on average across all regions, 37% of all participating households on-reserve were food insecure, while regional prevalence ranged from 30.8% to 45.5% or up to more than 5 times higher than the prevalence of household food insecurity in the general Canadian population (which was 8.8% in 2017-18)Footnote 35. For example, the PHAC has reported that First Nations peoples have a high prevalence of type 2 diabetes with 19%, double that of the general population. Additionally, the Canadian Journal of Public Health has reported that "a majority of First Nations households are not able to achieve a healthy diet either from the traditional food systems within their territory due to external considerations now compounded by the climate crisis, or from the market foodsystem due to financial constraints that limit access to diverse and high-quality market foods."

4.2 Mandate

Finding 2: The federal government has a clear mandate to continue to address the greater risks and lower health outcomes associated with chronic diseases among First Nations individuals, families and communities.

The organization of Canada's health care system is largely determined by the Canadian Constitution. Roles and responsibilities are divided between the federal, provincial and territorial governments.

- Generally, provinces and territories have primary jurisdiction over the administration and delivery of health care services in their respective jurisdictions. Provinces and territories receive transfer payments from the federal government to provide universally accessible and publicly insured health services to all residents, including Indigenous Peoples.

- The federal government is responsible for enforcing the general standards provided in the Canada Health Act, respecting provincial health insurance plans. As well, Parliament has exclusive legislative authority for "Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians" (Constitution Act, 1867, Section 91(24)).

- Indigenous communities also play a key role in the delivery of health services and programming.

It is important to note that the Canada Health Act, 1984, outlines the intent of Canadian health care policy in general and describes the conditions under which provincial and territorial governments qualify for the Canada Health Transfer. Further, section 3 of the Canada Health Act, 1984, states that Canadian health care policies are intended to ensure the physical and mental well-being of Canada's residents, and to facilitate reasonable access to health care, including Indigenous Peoples.

First Nations health jurisdiction is complex in nature. While the Constitution Act, 1867, and the Indian Act, 1876, identify jurisdictional responsibilities regarding Indigenous health care services, there is currently no legislation in place that provides clarity on the roles and responsibilities of different levels of governments in health care for Indigenous Peoples. It is important to note that under section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867, the federal government has power to enact health legislation based on its "peace, order and good government" powers (e.g., laws pertaining to quarantine and national emergencies). In 2021, the Minister of Indigenous Services Canada was mandated to "co-develop distinctions-based Indigenous health legislation, backed with the investments needed to deliver high-quality health care for all Indigenous Peoples", which would improve access to high-quality, culturally relevant health services. Multiple streams of engagement are currently underway.

At present, the federal government provides health services to First Nations and Inuit as a matter of policy, as guided by the 1979 Indian Health Policy as well as the Indian Health Transfer Policy. The Indian Health Policy was adopted during a period of transition for FNIHB whereby FNIHB began to shift more towards helping communities gain more direct control over community-based health services rather than providing direct health care services. The Indian Health Policy also recognizes the interdependent nature of the Canadian Health system and identifies that two of the most significant federal roles are in public health activities on reserves and health promotionFootnote 36. Further, the Indian Health Policy describes the importance of reinforcing relationships between multiple levels of government and increasing the capacity of Indigenous communities to "play a positive and active role within the Canadian health care system"Footnote 37. As a result of the Policy, the federal government no longer directly provides services to First Nations people in the Northwest Territories, nor to the four Inuit regions: in Nunavut, the Inuvialuit Regional Settlement in the Northwest Territories, Nunavik in Quebec, and Nunatsiavut in Newfoundland and Labrador. Instead, federal government funding flows through transfer agreements with territorial governments and self-governments/land claim agreements.

During the Healthy Living evaluation timeframe, the Prime Minister implemented a recommendation from the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996) by dissolving Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, and replacing it with two new departments: Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC). In 2017, Indigenous Services Canada assumed control of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, which was transferred from Health Canada. The Department of Indigenous Services Act (2019), provides for a legislative mandate for Indigenous Services Canada to work towards the transfer of departmental responsibilities and collaborate with Indigenous partners in all aspects of service delivery, including health.

In addition to the creation of the new ISC Department, the 2017 mandate letter to the Minister of Indigenous Services stated as one of the top priorities: "Lead work to create systemic change in how the federal government delivers health services to Indigenous Peoples in collaboration with the Minister of Health and the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs. Specifically, I would ask that you take an approach to service delivery that is patient-centred, focused on community wellness, links effectively to provincial and territorial health care systems, and that considers the connection between health care and the social determinants of health."Footnote 38

Budget 2018 also laid out the renewal of the Tobacco Strategy. The budget called for distinctions-based approaches and stated that, "the Government of Canada recognizes that a distinctions-based approach is needed to ensure that the unique rights, priorities and circumstances of First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation are acknowledged, affirmed and implemented."Footnote 39 In line with this, the FTCS was redesigned as CTS and included a distinctions-based, Indigenous-specific component. ISC key informant interview respondents (national and regional) noted that distinctions-based approaches have and will better equip the program to meet the needs of communities.Footnote 40 The 2018 budget also highlighted the significant gaps in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and the higher diabetes prevalence rate faced by Indigenous peoples.Budget 2018 specifically states that "infant mortality rates of First Nations and Inuit children are up to three times higher, diabetes rates are up to four times higher (than Indigenous people)…this gap in health outcomes can be narrowed, and providing access to quality health care close to home is an essential part of that change."Footnote 41 The 2016 federal budget also "allocated $64.5M over five years, beginning in 2016-17, and $13.8M per year ongoing to expand Nutrition North Canada (NNC) to support all northern isolated communities. This included funding to also expand NNC Nutrition Education Initiatives, managed by FNIHB, to newly eligible First Nations communities."Footnote 42

5.0 Key Findings: Effectiveness

A consistent challenge faced by the evaluators was the lack of available and adequate outcome-specific data to properly assess the achievement of both the program's immediate and intermediate outcomes. Part of this challenge was due to the evaluation being conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which directly impacted the evaluation's team ability to conduct site visits and thus to collect end user/client data from HL Program recipients.

Collection of data on indicators for the HL Program is obtained from various sources including what is reported by communities or funding recipients depending on the type of funding agreement they are in. With the move towards more flexible funding arrangements, many of which (flex and block funding) allow First Nations communities to allocate health-related funds as they see fit given the realities and context within their communities, the potential could exist for even less reporting on health-related indicators by communities. Consequently, the main source of data relating to the health-related indicators under the HL Program are: the community-based reporting template (CBRT)Footnote 43, a data collection tool that is utilized by some communities depending on their funding agreement type; and the national Regional Health Survey undertaken by FNIGC approximately every four to five years. While this survey is significant, it is limited in providing specific Healthy Living outcomes. As such, the evaluation relied on triangulated data sources from the Regional Health Survey (RHS), administrative data as well as limited qualitative and quantitative evidence provided by key informant interviews and survey responses. Challenges around data and reporting are further expanded on in section 6.5 below.

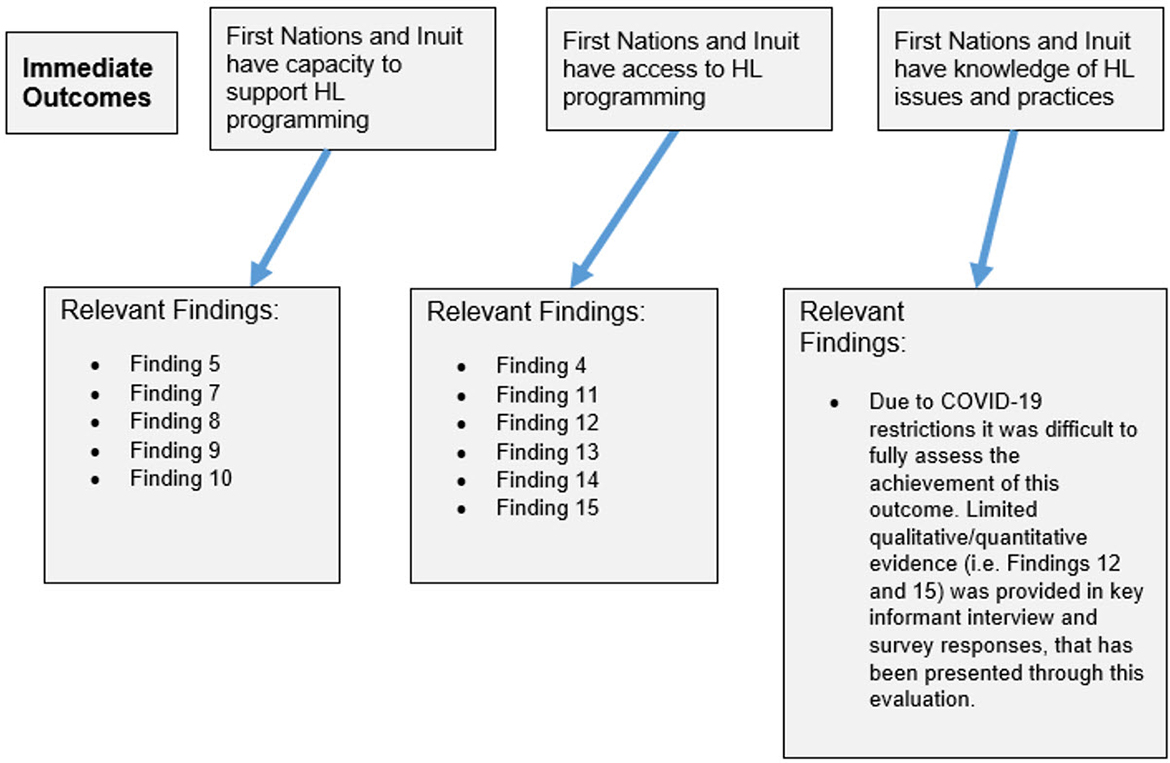

5.1 Overall Achievement of Expected Immediate Outcomes

Immediate Outcome #1: First Nations and Inuit have capacity to support HL programming

An important component of enhancing the knowledge, skills and abilities of community workers is access to appropriate training and professional development opportunities. Both key informant interview respondents and survey respondents identified the importance of community staff accessing capacity building opportunities to better meet the needs of the local community.

The 2014 Evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Healthy Living and Healthy Child Development, identified staff retention as a challenge in building community capacity, an issue that this evaluation has also noted continues to persist. Community-based capacity is increasing, however the high turnover of community-based staff is slowing that progress in some communities, whilst other communities have ongoing staff shortages to adequately deliver the sub-programs of the Healthy Living Program. Staff turnover has cost implications for communities with regards to training and capacity building as communities are often losing corporate memory, and there exists a constant need to train new staff.

Twenty-nine percent of survey respondents (n=92) indicated that training was sufficient, while 36% agreed that training is only somewhat sufficient to help them perform their jobs. At least 11% of survey respondents felt that training was not sufficient to support them in delivering Healthy Living sub-programs and 24% were not sure. Specific to the ADI program, 51% of survey respondents (n=80) agreed or strongly agreed that the ADI is succeeding in supporting efforts with regards to capacity building and training, 24% disagreed or strongly disagreed that the ADI is succeeding in supporting efforts with regards to capacity building and training and 25% were neutral.

A notable achievement of the ADI sub-program was the strong engagement of regional partners at their respective regional community of practice groups, which key informant interview respondents have referred to as "working groups." Key informant interview respondents across all regions expressed a high degree of satisfaction with this participatory working method and stated that the opportunities to build strategic partnerships with other colleagues at the national, regional and community levels have been beneficial.

As many key informant interview respondents noted, there is a strong desire for professional development opportunities, however the lack of appropriate funding has impacted the availability of professional development training opportunities for staff to further upgrade their skills and gain valuable knowledge across the sub-programs.

As a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an increase in the participation of staff in remote communities accessing online training opportunities. This uptake was viewed by ISC key informant interview respondents as a positive, cost-effective means for staff to access training opportunities without having to physically travel to training sites. The community planning and program componentsFootnote 44 in the 2014 Evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Healthy Living and Healthy Child Development, also concluded that Health Directors were making efforts to provide remote training opportunities for staff in remote communities in response to the inadequate training fundsFootnote 45.

Immediate Outcome #2: First Nations and Inuit have access to HL programming:

Access to the HL programming refers to the extent to which First Nations are able to offer the sub-programs in their communities, and for those that offer programs in their communities, the extent to which services were accessible for community members.

Funding arrangements are not program specific, rather they depend on the type of funding arrangement negotiated with the community or funding recipient. For example, in each community that the HL programming operates in, all the sub-programs (i.e., NNC, ADI, and CTS) can be found to be in the same funding arrangement.Footnote 46 However, the NNC Nutrition Education Initiative is only eligible in isolated northern communities based on the Crown Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) determined eligibility criteria for the overall NNC program. Many key informant interview respondents, including ISC national and regional staff and community health staff, expressed concerns that the eligibility for Nutrition Education Initiatives funding was dependent on the First Nations community meeting eligibility criteria for the Nutrition North Canada subsidy administered by CIRNAC. If the community does not qualify for subsidies under CIRNAC, the community also loses eligibility for ISC funding for Nutrition Education Initiatives. Communities expressed the continued need for nutrition education after communities no longer qualify for the Nutrition North Canada subsidy, stating that nutrition education remains relevant.

Participation in the Healthy Living Program is open to all community members. At the same time, 36% of survey respondents (n=114) agreed or strongly agreed that the Healthy Living Program was reaching all community members (22% were neutral, 35% disagreed or strongly disagreed, 7% did not know). Impressively, from 2013-2014 to 2017-2018, the community-based reporting template (CBRT) has been reported to maintain strong client access levels. For example, the CBRT reported that 91.2% of First Nations communities provided HL Programs in 2017-2018 and 88.9% First Nations communities delivered physical activities in the same year (table 1).

| 2013-2014 CBRT | 2014-2015 CBRT | 2015-2016 CBRT | 2016-2017 CBRT | 2017-2018 CBRT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | % of First Nations communities providing Healthy Living programs | 89.1% | 92.1% | 92.5% | 94.7% | 91.2% |

| 2 | % of First Nations communities that deliver physical activities | 86.2% | 87.6% | 88.1% | 91.6% | 88.9% |

| 3 | % of First Nations and Inuit communities that deliver healthy eating activities under the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative | 87.8% | 88.2% | 90.3% | 92.6% | 88.5% |

Specifically regarding the ADI sub-program, key informant interview respondents highlighted that it is often difficult to engage with the working age population, given that programming typically occurs primarily during the standard working hours. Targeted programming that accommodated clients' schedules could improve participation of this group. It was also noted that in many cases, the same group of individuals consistently participates in the Program.

As of 2017-18, 56% of First Nations and Inuit communities had access to tobacco control activities,Footnote 47 1578 new smoke-free spaces, and 129 new smoking-related resolutions.

In many cases, and as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the HL Program has successfully pivoted to providing programming online by leveraging communications technology and social media (for example, cooking classes delivered via Facebook rather than in-person). This has also allowed for new clients who would not otherwise have access to targeted activities to attend online activities. While this has worked effectively in some areas, there continues to remain accessibility challenges for community members living in remote areas with limited internet access.

Immediate Outcome #3: First Nations and Inuit have knowledge of HL issues and practices:

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the evaluation team was unable to conduct direct site visits for this evaluation. However, relevant to this outcome, the RHS reports that 59.2% (2015-16) of First Nations adults with diabetes, attended a diabetes clinic. The pandemic also directly impacted the evaluators' ability to interview community partners and thus determine the achievement of this outcome. In addition, since many community partners were involved in the response to COVID-19, the evaluators were unable to fully engage them as planned. That being said, limited qualitative and quantitative evidence was provided in the key informant interview and survey responses presented throughout this evaluation, that suggests that First Nations and Inuit have knowledge of HL issues and practices.

5.2 Operational EffectivenessFootnote 48

Finding 3: Both key informant interview respondents and survey respondents reported that the Healthy Living Program is operating effectively, however the flexibility of the program to tailor to each community's needs makes overall effectiveness difficult to determine.