Application of the Human Development Index to Self-Identified Métis in Canada, 2006 to 2016

On this page

Why we did this

The Human Development Index (HDI) has been published by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) since 1990. It provides a framework for examining countries’ progress on 3 components: health, income and education. Canada is among the highest ranking countries on the HDI with "very high" levels of human development. The previous HDI methodologyFootnote 1 was used as a framework to examine the HDI scores of the self-identified MétisFootnote 2 population in Canada, comparing the results to those of non-Indigenous Canadians between 2006 and 2016.

What we did

We adapted the 2018 UNDP HDI methodology for a Canadian context to compare the human development of self-identified Métis to other Canadians based on the 3 HDI components between 2006 and 2016:

- Health is measured by life expectancy at birthFootnote 3

- Education is measured by the average years of schooling for those aged 25 and older and the percentage of the population aged 15 to 34 attending schoolFootnote 3

- Income is measured by average (per capita) income for the entire population with and without incomeFootnote 4

These indicators are combined to form an index that is scaled between 0 and 1.0. The component scores and national HDI score were scaled to allow for international comparisons, allowing the ranking of self-identified Métis to be compared with the 2018 rankings of Canada as a whole, as well as 189 other countries. Further comparisons to previous HDI scores or rankings cannot be made due to many changes in the UNDP calculation of the HDI, its components and available data sources.

What we found

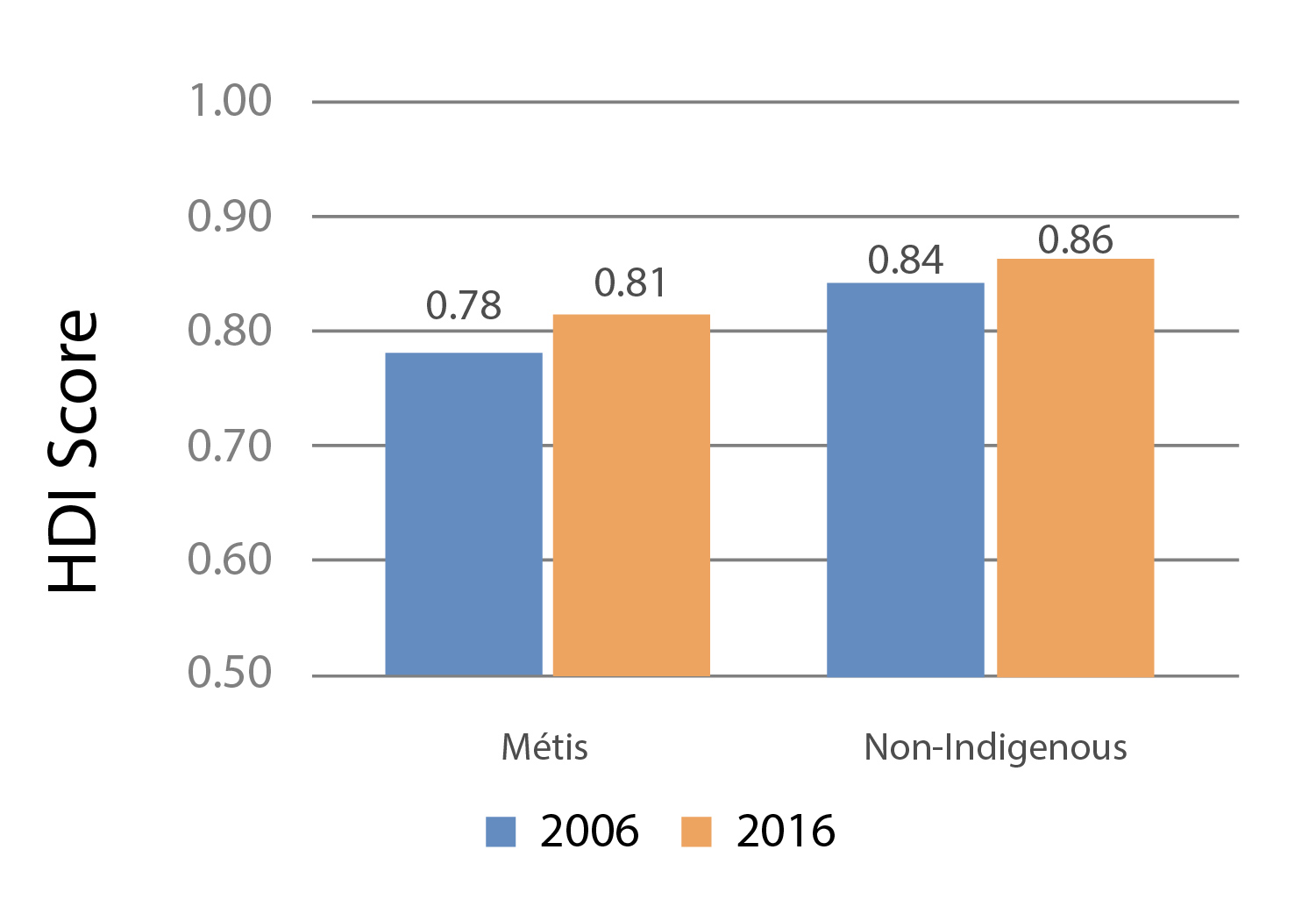

While national HDI scores increased between 2006 and 2016, the gap in HDI scores between self-identified Métis and non-Indigenous Canadians remained relatively stable (see Figure 1).

The change in self-identified Métis HDI scores between 2006 and 2016 was also consistent across most provinces. The improvement was greatest in Alberta and Ontario. HDI scores were lowest in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Overall HDI scores could not be calculated for the Atlantic provinces or the territories due to smaller populations.

While life expectancy improved for both self-identified Métis and non-Indigenous Canadians from 2006-2016, it improved less for self-identified Métis, widening the life expectancy gap and contributing the most to the overall difference in HDI scores. The education gap improved only slightly, and the income gap widened over the period.

While Canada ranked 12th internationally in 2018, self-identified Métis would have ranked 30th among countries with "very high" human development.

Figure 1. Human Development Index Scores for self-identified Métis and non-Indigenous Canadians, 2006 and 2016.

| Year | Self-identified Métis HDI score | Non-Indigenous Canadian HDI score |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 0.78 | 0.84 |

| 2016 | 0.81 | 0.86 |

What it means

The HDI scores for self-identified Métis were lower than those of non-Indigenous Canadians in both 2006 and 2016. While gains were made for self-identified Métis, they were often smaller than those of non-Indigenous Canadians, leading to a widening of pre-existing gaps.

For more information

To obtain a PDF version of the full report, Cooke, M. (2019). Application of the Human Development Index to Self-Identified Métis in Canada, 2006–2016. Ottawa: Indigenous Services Canada, or for other inquiries, please e-mail aadnc.recherche-research.aandc@canada.ca.