Evaluation of the Water and Wastewater On-Reserve Program

March 2021

Evaluation Directorate, Evaluation and Policy Redesign

PDF Version (671 KB, 48 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Program Description

- 3. Evaluation Methodology

- 4. Findings: Relevance

- 5. Findings: Water and Wastewater Infrastructure

- 6. Findings: Environmental Public Health Program

- 7. Findings: Training and Capacity Development

- 8. Findings: Roles and Relationships

- 9. Findings: Best Practices

- 10. Early Impacts of COVID-19

- 11. Conclusions and Recommendations

- 12. Recommendations

- Appendix A: Evaluation Questions and Issues

List of Acronyms

| AFN |

Assembly of First Nations |

|---|---|

| API |

Annual Performance Inspection |

| CBWM |

Community-Based Water Monitor |

| CFMP |

Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program |

| CRTP |

Circuit Rider Training Program |

| EPH |

Environmental Public Health |

| EPHO |

Environmental Public Health Officer |

| EPHD |

Environmental Public Health Division |

| EPHP |

Environmental Public Health Program |

| EPHS |

Environmental Public Health Services |

| FNHA |

First Nations Health Authority |

| FNIHB |

First Nations and Inuit Health Branch |

| FNIIP |

First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plan |

| FNWWAP |

First Nations Water and Wastewater Action Plan |

| FNWWEP |

First Nations Water and Wastewater Enhancement Program |

| GCDWQ |

Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality |

| ICMS |

Integrated Capital Management System |

| INAC |

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada |

| ISC |

Indigenous Services Canada |

| LT-DWA |

Long-term Drinking Water Advisory |

| O&M |

Operation & Maintenance |

| OFNTSC |

Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation |

| PWS |

Public Water System |

| RIDB |

Regional Infrastructure Delivery Branch |

| RO |

Regional Operations |

| SWM |

Strategic Water Management |

| SWPP |

Source Water Protection Plan |

| TB |

Treasury Board |

| TSAG |

Alberta First Nations Technical Advisory Services Group |

| WSO |

Water System Operator |

| WWP |

Water and Wastewater Activities On-Reserve Program |

Executive Summary

This evaluation of the Water and Wastewater Activities On-Reserve program was outlined in the fiscal year 2018-19 Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) Five Year Evaluation Plan, and conducted in compliance with the Treasury Board of Canada Policy on Results. The evaluation was undertaken to provide a neutral and evidence based assessment of: relevance; relationships; best practices; and, performance in the areas of infrastructure, environmental public health activities and training and capacity development.

Background

This evaluation focuses on two programs:

- Infrastructure and Capacity Program - Water andWastewater, also referred to as the First Nations Water and WastewaterEnhancement Program. The key activity is the provision of proposal-basedfunds under the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program for the planning, procurement, design, construction/acquisition, commissioning, assessment, and operations and maintenance of public water and wastewater systems. The ultimate goal is that First Nations people have reliable and sustainable public water and wastewater systems in their communities.

- Public health-related water and wastewater activities supported by the Environmental Public Health Division of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch within ISC. The Environmental Public Health Program provides direct or financial support to First Nation communities south of 60° for a range of public health-focused water and wastewater activities including drinking water quality monitoring for bacteriological and chemical parameters. The ultimate goal is that First Nations, Inuit and partners contribute to decreased environmental public health risks.

Evaluation Scope and Methodology

The scope of the evaluation covers the years 2012-2013 to 2016-2017 and also selected activities undertaken from March 2017 up to March 2019 to recognize and provide feedback on new initiatives stemming from Budget 2016.Footnote 1 The evaluation was led by an evaluation team from the Evaluation Directorate within ISC, supported by an external consultant. Additionally, although not within its original scope, the evaluation outlines early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic upon the Water and Wastewater Activities On-Reserve Program, as well as how it has addressed them.

The Methodology Report was approved in September 2019, with primary data collection occurring from September 2019 to February 2020 and September to October 2020. The evaluation relied on a mixed-methods approach that included the following lines of evidence: a document, literature and media review; 35 key informant interviews; survey of 221 First Nations water and wastewater system operators and managers; survey of 52 community-based water monitors; and site visits to 6 First Nations communities in Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, British Columbia and Alberta.

Key Finding

Relevance

The evaluation found that there is a continued need for investment in infrastructure, operations and maintenance, training and capacity development for water and wastewater systems in First Nations communities. While significant progress has been made towards achieving the Government of Canada's commitment of eliminating all long-term drinking water advisories on public systems on reserves, continued investment is needed to achieve this goal. There is also a continued need to provide environmental public health services to First Nations communities.

Performance – Water and Wastewater Infrastructure

Overall, the significant investments that have been made towards improving water and wastewater infrastructure in First Nations communities have been achieving results. As of September 30, 2020, 365 water and wastewater projects were completed and an additional 292 projects were ongoing for a total of 657 water and wastewater projects across 581 First Nations communities. Key informants stated that the First Nations Water and Wastewater Enhancement Program is doing well at addressing the highest priority systems, but even with the additional funding provided by Budget 2016 and subsequent funding, there are not enough resources to address all vulnerable systems. Wastewater systems, for example, have received far less investment and attention than drinking water systems. The share of public wastewater systems meeting the Wastewater Systems Effluent Regulations decreased from 80% to 66% between 2015-16 and 2019-20. Insufficient Operation & Maintenance funding poses immediate risks to infrastructure and undermines its longevity.Footnote 2 Climate change poses potential significant future risks to source water and community infrastructure.

Performance – Environmental Public Health Program

The percentage of First Nations communities with access to trained community-based water monitors or environmental public health officers to monitor drinking water quality has met the program target of 100%. All community sites had access to portable test kits from 2012/13 to 2016/17 and the average sampling frequency was 80% in 2016/17 which is close to the target of 84% set for 2021-22. Nearly all (99%) public water systems are monitored for routine/annual chemical parameters. Most (89%) of the water/wastewater system operators surveyed agreed that the frequency of testing drinking water in their community is appropriate while 7% disagreed and 4% were unsure. The overall workload of environmental public health officers continues to be an area of concern. There are currently 108 environmental public health officers which is two thirds of what research indicates to be required to adequately deliver on all program areas (e.g. inspections of restaurants, daycare centres, etc.).

Performance – Training and Capacity Development

The proportion of primary water/wastewater system operators that are certified to the level of their water system has increased to 74% in 2019-20. The proportion of primary water/wastewater system operators that are certified to the level of their wastewater system was just 60% in 2019-20. Water/wastewater system operators noted that adequate opportunities for certification training are available, but other factors limit overall certification rates including water/wastewater system operators turnover and lack of certified back-up water/wastewater system operators, as well as community remoteness and other barriers to advanced education. The Circuit Rider Training Program is considered by key informants to be an effective way of providing on-going hands-on training, support, and continuing education credits for water/wastewater system operators. The Circuit Rider Training Program is a long-standing program but does not have secure long term funding as this is provided only on an annual basis. Several key informants indicated that in the absence of the Circuit Rider Training Program, the number of drinking water advisories would increase substantially over time, as there would not be a sufficient number of trained water/wastewater system operators with the required knowledge to operate the water and wastewater systems. Effective training of community-based water monitors by the environmental public health officers ensures that all individuals that take drinking water samples in First Nations communities receive the required training prior to sampling.

Relationships

With respect to the First Nations Water and Wastewater Enhancement Program and the Environmental Public Health Program, the distinction between infrastructure and public health means that there tends not to be overlap between ISC-Regional Operations and ISC-First Nations and Inuit Health Branch. The relationship between ISC-Regional Operations and ISC-First Nations and Inuit Health Branch programming has benefitted from the priority placed on eliminating long-term drinking water advisories and has resulted in opportunities to develop relationships that may not yet exist with respect to other program areas. Key informants reported that the overall relationship between ISC-Regional Operations and ISC-First Nations and Inuit Health Branch is said to be improving both in the regions and at headquarters. The focus on eliminating long-term drinking water advisories has been accompanied by a move towards more centralized decision making as opposed to regional prioritization of projects. However, this has not adversely impacted the relationship.

Best Practices

A wide range of best practices were emphasized by key informants or described in the literature, media and documents reviewed for this evaluation. They are summarized in this report and relate to: the transformation of ISC; prioritization of long-term drinking water advisories; support for water/wastewater system operators and systems; procurement design and construction; municipal type agreements; outreach and promotion of the profession; and, planning for sustainable systems.

Early Impacts of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on both normal, planned, and periodic Water and Wastewater Activities On-Reserve Program activities. Both the infrastructure and public health aspects of the program have been affected. The impacts include: delays in planned infrastructure construction and repair activities on-reserve due to restricted access to communities and travel restrictions for both ISC personnel and outside contractors; backlogs in routine water inspections and sampling; increased costs (as a result of delays), as some work may only be done seasonally, and increased stress on ISC regional staff as they support the COVID-19 response.

Recommendations

- Implement policy and procedures that result in the federal government providing 100% of the operation & maintenance costs for water and wastewater infrastructure in First Nations communities. Insufficient operation & maintenance funding contributes to the occurrence of drinking water advisories and long-term drinking water advisories, decreased water system operator retention and certification rates, and reduced operational lifespan for infrastructure investments.

- Increase the number of wastewater infrastructure projects undertaken. To-date wastewater infrastructure projects have received disproportionally less attention and funding than drinking water projects. Many communities have inadequate wastewater services and much of the existing infrastructure has been assessed as a high or medium risk.

- Where applicable, support regions to provide 5-year rather than 1-year funding agreements for the Circuit Rider Training Program and where demand exists among First Nations communities, to expand the model to include other forms of infrastructure. Where used, the 1-year funding agreement model is inconsistent with the importance of the Circuit Rider Training Program and imposes unnecessary financial uncertainty on Circuit Rider Training Program administrators and circuit-rider trainers.

- Proactively incorporate climate change adaptation and mitigation into infrastructure design and construction as well as source water protection. The response to climate change impacts by the Water and Wastewater Activities On-Reserve Program has been primarily reactive instead of proactive. Program engineers and environmental public health staff should be engaged to determine what relevant policies or guidelines could be implemented in the short-term and what additional data or information is required before additional policies or guidelines can be implemented.

- Determine the impact on First Nations communities by program area as a result of current environmental public health officer staffing levels and priorities. There is compelling evidence that the current number of Environmental Public Health Program environmental public health officers is insufficient, however, overall, the Program is able to deliver drinking water activities successfully. An evaluation of all Environmental Public Health Program program areas as opposed to a single area, as is the focus of this evaluation, is necessary to fully understand the impact of current staffing levels.

Management Response and Action Plan

Evaluation Title: Evaluation of the Water and Wastewater On-Reserve Program

Overall Management Response

Overview

- This Management Response and Action Plan was developed to address recommendations presented in the Evaluation of Water and Wastewater On-Reserve. It was developed by ISC-RO and ISC-FNIHB in collaboration with the Evaluation Directorate.

Assurance

- The Action Plan presents appropriate and realistic measures to address the evaluation's recommendations, as well as timelines for initiating and completing the actions.

Action Plan Matrix

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates | Action Item Context/Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Implement policy and procedures that result in the federal government providing 100% of the O&M costs for water and wastewater infrastructure in First Nations communities. | We do concur. | Director, |

Start Date: March 2021 |

In the 2020 Fall Economic Statement, tabled on November 30, 2020, $1.5 billion in new funding was announced to help accelerate the work being done to end all long-term drinking water advisories on public systems on reserves, to better support the operation and maintenance of systems, and to continue program investments in water and wastewater infrastructure. The increase of operations and maintenance funding from 80% of the formula funding currently provided to 100% funding for operations and maintenance will enable First Nations to better support approximately 1,200 water and wastewater systems, including:

|

1a) In the 2020 Fall Economic Statement, Canada committed $616.3 million from 2020-21 to 2025-26, and $114.1 million ongoing thereafter, to support 100% of the formula for O&M funding for water and wastewater on reserve. To deliver on this commitment, ISC will allocate the new O&M investments and revise the departmental policies and procedures to reflect the increase to 100% funding of the O&M formula for water and wastewater in First Nations communities. |

Completion: by Q4 2021-2022 (for allocation of first two years of new funding) |

|||

| 2. Increase the priority of wastewater infrastructure projects, which to-date have received disproportionally less funding than drinking water projects but pose potential risk to many communities. | We do concur. | Director, |

Start Date: March 2021 |

In the 2020 Fall Economic Statement, Canada committed an additional $553.4 million to help address vulnerable water and wastewater systems. These investments will ensure that the Department can continue to support the planning, procurement, design, construction, and commissioning of water and wastewater minor and major capital projects. This includes new builds, as well as system repairs and upgrades. Wastewater projects identified as priority may be addressed with this additional funding. Water and wastewater projects are funded from the same funding envelope; as such, water projects often take priority. As work proceeds to address LT-DWAs and vulnerable water systems, more wastewater projects will be able to be funded. |

2a) ISC will work with First Nations to address their wastewater infrastructure, with an increased focus on addressing potential risks posed to communities. Regional offices will prioritize projects at the regional level, which will ensure more critical wastewater projects are funded. To assess progress, this will be regularly tracked and reported. The national prioritization process for water and wastewater will at the same time be refocused to better allow for those regional priorities including wastewater projects posing a risk to human health or the environment, shifting away from centralized decision making which focused predominately on long-term drinking water advisories. To assess progress, this will be regularly tracked and reported. |

Completion: Q4 2022-2023 |

|||

| 3. Where applicable, support regions to provide 5-year rather than 1-year funding agreements for the CRTP and where demand exists among First Nations communities, to expand the model to include other forms of infrastructure. | We do concur. | Director, |

Start Date: January 2021 |

The CRTP is a long-term capacity development program that has been successfully implemented for water and wastewater infrastructure and provides training and mentoring services to operators. It is designed to raise the competency and confidence level of maintenance personnel while improving asset condition and longevity. |

3a) ISC will develop a plan to put in place 5-year funding agreements for the remaining interested regions who have in place 1-year funding agreements for CRTP. ISC HQ continues to work with regions around this item. ISC will also continue to support capacity development and operator support programs more broadly, for example, through regional technical hubs. |

Completion: Q2 2022-2023 |

|||

| We do concur. | Director, |

Start Date: March 2021 |

|

|

3b) The Department is exploring options for the expansion of the CRTP to schools and other public community infrastructure in First Nation communities. Engagements within the Department (Regions, FNIHB and RO) are underway. This new Program will be subject to funding approval. |

Completion: TBC, subject to funding approval |

|||

| 4. Develop policies or guidelines that incorporate climate change adaptation and mitigation into infrastructure design and construction as well as source water protection. | We do concur. | Director, Strategic Water Management, Regional Operations and RO Regions |

Start Date: March 2021 |

|

4a) ISC will work with partners and First Nations to identify actions for climate change adaption and mitigation measures to be integrated into water and wastewater infrastructure design and construction. |

Completion: Q4 2022-2023 |

|||

| We do concur. | Director, Strategic Water Management, Regional Operations and RO Regions |

Start Date: July 2020 |

ISC is currently reviewing, with First Nation partners, its water and wastewater policies and protocols, which presents an opportunity to better address climate change considerations with respect to water and wastewater infrastructure. |

|

4b) As part of the on-going policy and protocol review, ISC will incorporate climate change adaptation and mitigation considerations into its water and wastewater policies where relevant. |

Completion Q4 2021-2022 for completion of review |

|||

| We do concur. | Sustainable Operations Directorate (SOD), RIDB in partnership with Director, Strategic Water Management, RO, and RO Regions |

Start Date: March 2021 |

First Nations are the owners and operators of their water and wastewater systems; ISC provides financial support and technical advice. In the context of infrastructure projects, the most appropriate means of addressing these issues is through the feasibility and design work of the First Nation's consultants. |

|

4c) ISC will work with First Nations partners to develop an analysis or guidance on how climate change adaptation and mitigation measures may be considered in the terms of reference for infrastructure design, thereby requiring their consultants to include these considerations in the design and construction of infrastructure. |

Completion: Q4 2021-2022 for an analysis/guidance on how climate change considerations may be considered in design |

|||

| 5. Determine the impact on First Nations communities by program area as a result of current EPHO staffing levels and priorities. | We do concur. | Director, Environmental Public Health Division, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch |

Start Date: March 2021 |

Existing evidence (gap analysis, PM deep dives) have showed that additional EPHOs are needed to address longstanding program integrity gaps in environmental public health services provided in First Nations communities south of 60. This includes the provision of environmental public health services in eight core areas: food safety, housing, solid waste disposal, communicable disease control, emergency preparedness and response, drinking water, and wastewater, regardless of the source of the funding. EPHOs are assigned communities to which they provide all eight of these services at the request of and in consultation with the communities. EPHOs in regions with the greatest gaps in EPH services serve a greater number of communities. In addition to its previous annual reporting on the number of inspections done the Program will undertake a more detailed comparative analysis of inspections done over the last 5 fiscal years (16/17 - 20-21) in all core areas. The analysis will include looking at: the number and frequency of inspections against the National Framework; observations/risks recorded; and the number of EPHOs. This report will look to detail, given current EPHO numbers, the ability of the Program to meet the National Framework and identify potential risks and hazards in First Nations communities. A special focus is put on food safety and food facilities given previous analysis showing the relatively high number of critical violations. |

5a) Produce a synthesis report that will use existing and future reports and documentation to evaluate and better understand the impact of the current EPHO numbers on the ability of the Program to meet the National Environmental Public Health Program Framework, and look to identify trends regarding potential risks and hazards observed during inspections in First Nations communities. |

Completion: By the end of Q3 2022-2023 – Complete a comparative analysis of inspection data from the last five fiscal years (16/17 to 20/21). |

|||

| We do concur. | Director, Environmental Public Health Division, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch |

Start Date: March 2021 |

Context is provided above |

|

5b) Program will undertake an analysis of EPHO gaps on food safety/food facilities and potential risks to health of community members and identify potential mitigation measures. |

Completion: By Q2 2021-2022 – Complete analysis of food facility data from 2018-2019 to 2019-2020, including a comparative analysis by fiscal year |

1. Introduction

The overall purpose of the evaluation was to examine the Water and Wastewater Activities On-Reserve Program (WWP) and its constituent programs and policy areas, as outlined in the Five Year Evaluation Plan of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), and in compliance with the Treasury Board (TB) of Canada Policy on Results. The two areas of focus were: the Infrastructure and Capacity Program - Water and Wastewater, also referred to as the First Nations Water and Wastewater Enhancement Program (FNWWEP); the second is public health-related water and wastewater activities supported by the Environmental Public Health Division (EPHD) of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) within ISC.Footnote 3

2. Program Description

2.1 Background

Responsibility for safe drinking water on reserves is shared between First Nations communities and the Government of Canada.

ISC-RO provides funding and advice regarding planning, procurement, design, construction, upgrading, operation and maintenance and commissioning of water treatment facilities on First Nations reserves. They also provide financial support for the training and certification of water system operators.

ISC-FNIHB works with First Nation communities to protect public health by assuring verification monitoring programs are in place to provide a final check on the overall safety of drinking water at tap in public water systems, semi-public water systems, cisterns and individual wells in First Nations communities.Footnote 4 ISC-FNIHB monitors systematically all systems with 5 or more connections, as well as systems with less than 5 connections where the public has a reasonable expectation of access. For remaining systems, ISC-FNIHB offers residents, upon request and free of charge, bacteriological testing services of their well water.

Chief and Council are responsible for planning and developing their capital facilities that provide for the basic infrastructure needs of the community, including drinking water. They are also responsible for the day-to-day operation of water and wastewater systems on reserves, including sampling and testing drinking water (operation monitoring).

FNWWEP

The FNWWEP is part of the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program (CFMP), the umbrella program for ISC-RO's infrastructure investments in Indigenous communities. Decisions on project funding are built around the First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plan (FNIIP) process, where communities submit proposals to ISC based on their infrastructure needs. ISC's regional offices align those needs with program criteria, priorities, and resources. ISC's headquarters ensures accountability and the allocation of funds to regions, which are then distributed to Indigenous communities. Oversight is principally provided through the regional offices, which oversee cost-effectiveness by ensuring that projects are publicly tendered, and through the ISC Operations and Service Delivery Committee, which provides high-level oversight for major projects which could have significant national, risk, resource, or policy impacts. The FNWWEP is managed by ISC-RO, where both the Strategic Water Management (SWM) Team, ISC-RO regional offices, and the Regional Infrastructure Delivery Branch (RIDB) manage delivery through the CFMP.

ISC-RO Regional offices update the First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plans to support ongoing investment decisions, perform monitoring tasks as required by risk assessments, and proactively communicate project issues to the Regional Infrastructure Delivery Branch (RIDB) for early interventions. The RIDB supports regional offices in the management of projects, and provides additional oversight on specific projects as necessary.

Headquarters distributes program funds to the regional offices following priority-ranking exercises. Once a project is approved, the regional offices oversee project delivery and compliance with departmental policies and directives, which include requirements for competitive procurement and value for money.

The key activity in the FNWWEP is the provision of proposal-based funds under the CFMP for the planning, procurement, design, construction/acquisition, commissioning, assessment, and operation and maintenance of public water and wastewater systems. From this activity, the program funds three outputs:

- Capital projects related to public water and wastewater systems: focusing on the planning, design, construction, renovation, and/or repair/replacement of water and wastewater systems in First Nations communities on-reserve.

- Assessments of public water and wastewater systems: ensuring ISC and First Nation communities have the information they need to make strategic decisions and allocate resources to manage public water and wastewater systems within established health and safety standards.

- Training and capacity building: funding for supporting First Nation communities to develop the skills and capacity to operate and maintain their water and wastewater systems, as well as water quality testing.

EPHP

The primary objective of the EPHP is to "identify, address, and/or prevent human health risks to First Nations and Inuit communities associated with exposure to hazards within the natural and built environments." Within ISC-FNIHB , the EPHP is coordinated regionally by Environmental Public Health Services (EPHS) and supported nationally by the Environmental Public Health Division (EPHD). All program activities are provided in agreement with and by request of First Nations Authorities.

In First Nations communities south of 60º, EPH programming is delivered by Environmental Public Health Officers (EPHOs) employed by ISC or First Nations communities and/or Tribal Councils. All EPHO by health organizations in Canada as evidence of satisfactory training and competency. Key programming under public health assessments continues to include activities that focus on eight core areas: Drinking Water; Wastewater; Solid Waste Disposal; Food Safety; Housing; Facilities Inspections; Environmental Communicable Disease Control; and, Emergency Preparedness and Response. The role of the EPHP is to assist communities by providing training and education around EPH risks according to community priorities, developing recommendations for addressing EPH risk based on investigations, and reviewing infrastructure plans from a public health engineering perspective. Key activities include public health inspections and assessments, public education and training, and providing advice and guidance. Environmental public health surveillance and risk analysis programming includes community-based and participatory research on trends and impacts of environmental factors, such as chemical contaminants and climate change on the determinants of health (e.g., biophysical, social, cultural, and spiritual).

Nearly half of EPHO serving First Nations communities are employed by First Nation communities or organizations, and in First Nations communities where Environmental Public Health Programs are transferred, the First Nations stakeholders are responsible for drinking water quality monitoring. More specifically, FNIHB works in partnership with First Nations communities south of 60 degrees parallel in Canada, excluding British Columbia, to monitor drinking water as per the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Monitoring. ISC-FNIHB works together with First Nations communities and provides funding to Chief and Councils for drinking water monitoring through its Community-Based Water Monitor (CBWM) program.Footnote 5

Community-Based Drinking Water Quality Monitors are trained by EPHO to sample and test the drinking water for potential bacteriological contamination as a final check on the overall safety of the drinking water at tap. If a community does not have a Community-Based Drinking Water Quality Monitor, an EPHO a Certified Public Health Inspector employed by ISC or First Nations stakeholders, will sample and test drinking water quality, with the community's permission.

EPHO test drinking water quality for chemical, physical and radiological contaminants and maintain quality assurance and quality control as part of the verification monitoring program. They also review and interpret drinking water quality tests and disseminate the results to First Nations communities. Under the OCAP principle, First Nations assert that the data belongs to First Nations. Drinking Water Advisories data is posted on the website on a real time basis where an authorization has been reached with all First Nations to do so.

In all situations, when a potential concern about the drinking water quality is identified, the EPHO will immediately communicate the appropriate recommendation(s) to Chief and Council for action such as issuing a drinking water advisory. In addition, ISC-FNIHB reviews plans for new and upgraded water treatment systems from a public health perspective, and assists First Nations in planning and siting the development of their individual sewage septic systems upon request. In First Nations communities where EPHPs are transferred, First Nations stakeholders are responsible for drinking water quality monitoring.

Operation Monitoring vs. Verification Monitoring

The water system operators (WSOs) perform operational water quality monitoring, using daily and weekly water quality tests of raw, treated and distribution system water as per a drinking water quality monitoring program for the system(s) under their responsibility. In turn, the Community-based Drinking Water Quality Monitor (CBWM) or EPHO perform the drinking water verification monitoring in the distribution system (at tap) to verify operational monitoring results.

2.2 Program Narrative

Both FNWWEP and EPHP activities align with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Call to Action #19, which calls upon "the federal government, in consultation with Aboriginal peoples, to establish measurable goals to identify and close the gaps in health outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities, and to publish annual progress reports and assess long-term trends."Footnote 6

The Government of Canada's 2015 Speech from the Throne promised a renewal of the relationship between Canada and Indigenous peoples and the Government's first budget proposed an end to long-term boil water advisories by investing an additional $1.8 billion over five years, starting in 2016-17. As part of Budget 2016, the Government formally announced their commitment to eliminate LT-DWAs by March 2021. As acknowledged by the Minister of Indigenous Services Canada in December 2020, the original target of March 2021 will not be achieved. The Government of Canada will continue to work in partnership with communities to end all LT-DWAs on public systems on reserves as soon as possible.

FNWWEP expected outcomes are:

Immediate Outcomes:

- Public water and wastewater systems are planned, designed, constructed/acquired, renovated and repaired/replaced in First Nation communities.

- ISC has the information it needs to make strategic decisions and First Nation communities have the information they need to allocate resources to manage their public water and wastewater systems within established health and safety standards.

- First Nation communities are supported in managing their public water and wastewater systems.

Intermediate Outcomes:

- First Nations' public water and wastewater systems meet established standards.

- First Nation communities have public water and wastewater systems that protect health and safety and which enable participation in the economy.

- First Nation communities have developed the skills and capacity to adequately operate and maintain their public water and wastewater systems and are, consequently, better equipped to transition to a multi-year and community infrastructure plan-based funding approach.

Ultimate Outcome:

- First Nations people have reliable and sustainable public water and wastewater systems in their communities.

EPHP expected outcomes are:

Immediate Outcomes:

- First Nations have access to EPH risk identification activities.

- First Nations, Inuit and partners have knowledge of EPH issues, risks and practices.

- First Nations have capacity to engage in investigation of environmental hazards.

Intermediate Outcomes:

- First Nations, Inuit and partners use environmental public health risk reduction practices.

Ultimate Outcome:

- First Nations, Inuit and partners contribute to decreased environmental public health risks.

3. Evaluation Methodology

3.1 Scope and Evaluation Issues

The scope of the evaluation covers the years 2012-2013 to 2016-2017 as per Treasury Board RequirementsFootnote 7 and also selected activities undertaken from March 2017 up to March and including fiscal year 2018-2019 to recognize and provide feedback on new initiatives stemming from Budget 2016. Moreover, although not part of the original scope, the evaluation also incorporates more recent data and actions taken by ISC to address water and wastewater programming on reserve in the narrative. The evaluation was led by an evaluation team from the Evaluation Directorate within ISC, supported by an external consultant. Additionally, although not within the original scope of the evaluation, it will also outline early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic upon the WWP, as well as how it has addressed those impacts.

The evaluation was undertaken to provide a neutral and evidence based assessment of: relevance; performance in the areas of infrastructure, environmental public health activities and training and capacity development; relationships; and, best practices. Appendix A of this report lists the specific questions and issues that guided the evaluation.

3.2 Design and Methods

The evaluation was led by a team from the Evaluation Directorate within ISC, supported by an external consultant. The Methodology Report was approved in September 2019, with primary data collection occurring from September 2019 to February 2020 and from September to October 2020.Footnote 8

The evaluation relied on a mixed-methods approach that included the following lines of evidence: a document, literature and media review; 35 key informant interviews with ISC-RO and ISC-FNIHB representatives and external stakeholders including the AFN , FNHA, OFNTSC and TSAG; a survey of 221 First Nations water and wastewater system operators and managers; a survey of 52 Community-Based Water Monitors (CBWM); and site visits to 6 First Nations communities in Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, British Columbia and Alberta.

Following the initial data collection phase described above, the evaluation team also investigated the impacts of Covid-19 on water and wastewater activities by conducting follow-up interviews with ISC-RO and ISC-FNIHB staff at both headquarters and in the regions.

3.3 Limitations

Site visits were carried out in communities located in the Atlantic, Alberta and British Columbia Regions, but not in other regions as a result of COVID-19 pandemic travel restrictions. Data collected from the survey of water and wastewater system operators and key informant interview data helped to compensate for the change to the data collection plan by providing data from regions that were not visited. The change in the number of site visits did not have an impact on the overall findings, conclusions and recommendations of the evaluation.

The survey of community-based water monitors was not available to CBWMs in all regions due to the availability of contact information from ISC regional offices. As a result, findings from the CBWM survey includes responses from only Quebec, Atlantic, Manitoba and Alberta regions.

3.4 Indigenous Engagement

The issue of water and wastewater on-reserve is of great significance to First Nations in Canada.Footnote 9 As such, Assembly of First Nations collaboration, input, and advice was sought to provide input into the evaluation in terms of scope, lines of inquiry, evaluation questions, and appropriate informants. Additionally, the evaluation team participated on-site at the Alberta First Nations Technical Services Advisory Group (TSAG) Regional Drinking Water Safety Forum conference in Calgary, AB, which brought together many water system operators (WSOs) and community-based water monitors from many First Nations communities in southern Alberta. The purpose of the Forum was to seek feedback from participants on service gaps and additional water and wastewater needs in First Nations communities, as well as to inform Program direction.

4. Findings: Relevance

4.1 Continued need for the FNWWEP

There is a clear and continued need for investment in infrastructure, O&M, training and capacity development for water and wastewater systems in First Nations communities.

ISC provides funding and support for over 725 water and 450 wastewater systems in approximately 620 communities with the goal of bringing on-reserve water and wastewater systems to a level of service comparable to what is enjoyed by Canadians living in other communities of similar size and circumstances.Footnote 10 This goal has not yet been achieved, as people living in some First Nations communities lack access to clean drinking water or adequate wastewater infrastructure, and too many water and wastewater systems are considered to be at a medium- or high-risk for failure.

Significant progress has been made in increasing the safety of drinking water in First Nations communities and towards meeting the federal government's commitment of eliminating all long-term drinking water advisories on public systems on reserves. Since November 2015, through these investments and the work undertaken in partnership with First Nations communities and other partners, the number of LT-DWAs in effect on public systems on reserves declined from 105 to 59 as of March 31, 2019.Footnote 11 However, continued investment is needed as new LT-DWAs on public systems on reserves continue to be issued and systems in many communities are approaching or have exceeded their expected life.

There is also a continued need to provide funding for operations and maintenance (O&M) as well as training and capacity development. These investments are necessary to ensure that First Nations community members have access to clean and safe drinking water and wastewater services and to avoid drinking water advisories. Appropriate levels of investment in O&M and WSO training maximizes the lifespan of infrastructure assets and 'protects' the investments made by government and communities.

According to key informants, there are several opportunities to expand the scope of the existing programming to focus on, for example, private wells, source water protection, and a greater focus on wastewater systems. Beyond these additional needs, many First Nations communities are growing and new subdivisions, schools, and a variety of other community buildings will require drinking water and wastewater services.

4.2 Continued need for the EPHP

There is a strong consensus that there is a demonstrable and continued need for the program to provide environmental public health services to First Nations communities with respect to their water and wastewater systems.

All people are entitled to basic public health provisions and most communities do not have the breadth of that expertise internally. While nearly half (45/108) of all EPHO have been transferred to First Nation entities such as Tribal Councils, there remains an ongoing commitment by the federal government to fund these positions. In addition, there is a strong consensus from key informants that there is a demonstrable and continued need for the Program.

Previous evaluations have found a similar need for the Program. The 2016 evaluation of Health Canada's First Nations and Inuit Health Branch's Environmental Public Health Program found that many First Nations communities continue to experience significant environmental public health risks compared with other Canadian communities including poor drinking water quality, poorly operated wastewater systems and a lack of certified WSOs; as such, the Program supports a continued and growing need among many First Nations communities to identify and address human health risks associated with exposure to hazards within natural and built environments.Footnote 12 The report states that there continues to be a strong, demonstrated need for a program like EPHP to influence health promotion and disease prevention outcomes in First Nations communities, and the need is expected to increase. Drinking water was cited as an EPH Risk area by 95% of EPHOs surveyed in 2016, up from 91% in 2011, and was identified as a high priority by 88% of respondents in 2016, more than for any other EPH risk area. Wastewater risks were cited as an EPH risk area by 72% of respondents, down from 80% in 2011. The 2015 evaluation of the CBWM Program also found a continuing need for the Program because it protects the health of residents of First Nations communities. The evaluation stated that the CBWM Program provides objective verification on the overall drinking water system and drinking water quality through: timely sampling and testing of water; community capacity by training Community-Based Drinking Water Quality Monitors; and, increased awareness of drinking water issues.Footnote 13

5. Findings: Water and Wastewater Infrastructure

5.1 Infrastructure

Significant investment in water and wastewater infrastructure in First Nations communities has reduced the number of long-term drinking water advisories and has led to some progress towards achievement of performance targets.

As of September 30, 2020, a total of 365 water and wastewater projects were completed and an additional 292 projects were ongoing for a total of 657 water and wastewater projects across 581 First Nations communities.

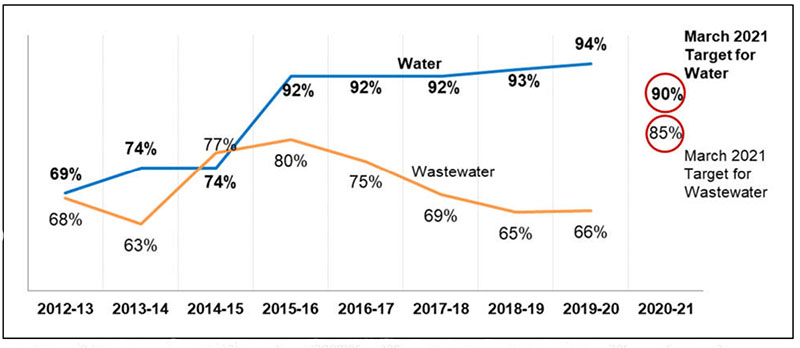

As shown in the figure below, the share of Public Water Systems with treated water that meets the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality (GCDWQ) reached 92% in 2015-16 and remained relatively constant for the five-year period from 2015-16 to 2019-20, thus meeting the March 2021 target of 90%. The share of Public Wastewater Systems producing treated effluent that meets the Wastewater Systems Effluent Regulations increased from 63% in 2013-14 to 80% in 2015-16 before declining to 66% in 2019-20. Despite this decrease, the 2017-18 ISC Departmental Results Report indicates that the 85% target for wastewater systems by March 2021 will be met as more infrastructure projects funded through Budget 2016 are completed.Footnote 14

Figure 1: Percentage of On-Reserve Public Systems meeting the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality and the Wastewater Systems Effluent Regulations

Source: Data provided by ISC Strategic Water Management Team. Targets contained in ISC Departmental Results Reports.

Text alternative for Figure 1: Percentage of On-Reserve Public Systems meeting the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality and the Wastewater Systems Effluent Regulations

Figure 1 is a line chart illustrating the percentage of on-reserve public systems meeting the guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality and wastewater systems effluent regulations by fiscal year.

In 2012-2013 the percentage of on-reserve public systems which met the guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality was 69%. The percentage of on-reserve public systems which met wastewater systems effluent regulations was 68%.

In 2013-2014 the percentage of on-reserve public systems which met the guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality was 74%. The percentage of on-reserve public systems which met wastewater systems effluent regulations was 63%.

In 2014-2015 the percentage of on-reserve public systems which met the guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality was 74%. The percentage of on-reserve public systems which met wastewater systems effluent regulations was 77%.

In 2015-2016 the percentage of on-reserve public systems which met the guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality was 92%. The percentage of on-reserve public systems which met wastewater systems effluent regulations was 80%.

In 2016-2017 the percentage of on-reserve public systems which met the guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality was 92%. The percentage of on-reserve public systems which met wastewater systems effluent regulations was 75%.

In 2017-2018 the percentage of on-reserve public systems which met the guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality was 92%. The percentage of on-reserve public systems which met wastewater systems effluent regulations was 69%.

In 2018-2019 the percentage of on-reserve public systems which met the guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality was 93%. The percentage of on-reserve public systems which met wastewater systems effluent regulations was 65%.

In 2019-2020 the percentage of on-reserve public systems which met the guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality was 94%. The percentage of on-reserve public systems which met wastewater systems effluent regulations was 66%.

The March 31, 2021 target for on-reserve public systems meeting the guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality is 90%. The March 31, 2021 target for on-reserve public systems meeting the guidelines for Canadian wastewater systems effluent regulations is 85%.

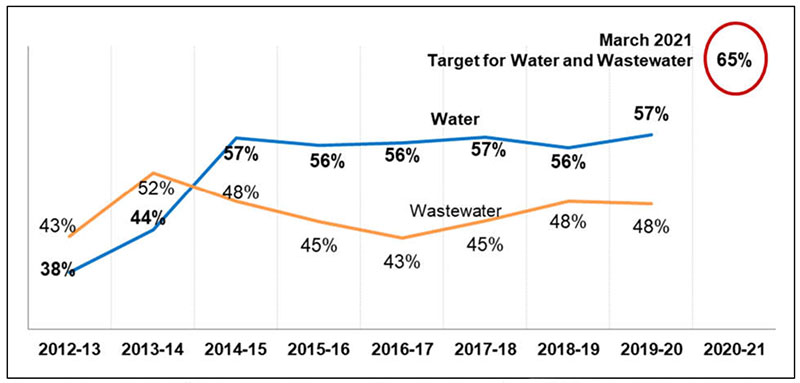

An evaluation of the management risk levels associated with each system is performed as part of the Annual Performance Inspection (API). An API assesses five main components of a system (i.e. effluent/water source risk; design risk; operation and maintenance risk; record keeping and reporting risk; and operator risk) to determine an overall system management risk score. Systems are given a risk score of low, medium or high.Footnote 15 As shown in Figure 2, the share of water systems with a low risk score increased between 2012-13 (38%) and 2014-15 (57%), but has been relatively consistent between 2014-15 and 2019-20 (57%). The share of public wastewater systems with a low risk score has fluctuated somewhat over the eight-year period, but the share in 2019-20 (48%) was the same as in 2014-15. The performance targets, which have not yet been achieved, call for the percentage of public systems that have low risk ratings to be 65% for both water and wastewater systems by March 31, 2021.Note de bas de page 16

Figure 2: Percentage of On-Reserve Public Water and Wastewater Systems that have Low Risk Ratings

Source: Data provided by ISC Strategic Water Management Team. Targets contained in ISC Departmental Results Reports.

Text alternative for Figure 2: Percentage of On-Reserve Public Water and Wastewater Systems that have Low Risk Ratings

Figure 2 is a line chart illustrating the percentage of on-reserve public water and wastewater systems that have a "low risk" rating.

In 2012-2013, 38% on-reserve public water systems had a low risk rating, and 43% of wastewater systems on-reserve had low risk ratings.

In 2013-2014, 44% on-reserve public water systems had a low risk rating, and 52% of wastewater systems on-reserve had low risk ratings.

In 2014-2015, 57% on-reserve public water systems had a low risk rating, and 48% of wastewater systems on-reserve had low risk ratings.

In 2015-2016, 56% on-reserve public water systems had a low risk rating, and 45% of wastewater systems on-reserve had low risk ratings.

In 2016-2017, 56% on-reserve public water systems had a low risk rating, and 43% of wastewater systems on-reserve had low risk ratings.

In 2017-2018, 57% on-reserve public water systems had a low risk rating, and 45% of wastewater systems on-reserve had low risk ratings.

In 2018-2019, 56% on-reserve public water systems had a low risk rating, and 48% of wastewater systems on-reserve had low risk ratings.

In 2019-2020, 57% on-reserve public water systems had a low risk rating, and 48% of wastewater systems on-reserve had low risk ratings.

The March 2021 target for on-reserve public water and wastewater systems having low risk ratings is 65%.

In the survey of WSOs undertaken to inform this evaluation, respondents were asked to rate the average quality of their community's water and wastewater infrastructure since 2013. As shown in the following table, those from Yukon (72%), Atlantic (50%), and Manitoba (50%) Regions were most likely to respond good or very good. Respondents from Alberta were the most likely to respond poor or very poor (40%). Since Alberta has very few LT-DWAs, the survey results imply that LT-DWAs are not always a comprehensive measure of a sustainable system.

| Province/Territory of Respondent |

Very Good or Good |

Satisfactory | Poor or Very Poor |

Not Sure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yukon (n=7) | 72% | 14% | 0% | 14% |

| Atlantic (n=10) | 50% | 40% | 10% | 0% |

| Manitoba (n=16) | 50% | 19% | 19% | 12% |

| Ontario (n=28) | 43% | 29% | 22% | 7% |

| Quebec (n=13) | 43% | 29% | 26% | 8% |

| British Columbia (n=100) | 39% | 42% | 14% | 5% |

| Saskatchewan (n=24) | 29% | 50% | 21% | 0% |

| Alberta (n=20) | 15% | 35% | 40% | 10% |

| Overall (n=218) | 38% | 38% | 18% | 6% |

| Source: Survey of Water System Operators, 2019 |

||||

WSOs were also asked to indicate if the quality of their community's water and wastewater infrastructure had improved, worsened or had not changed since 2013. As shown in Table 2, the share of respondents that indicated their community's infrastructure had improved ranged by region from a low of 22% (Ontario) to a high of 50% (Manitoba), while the share that indicated it had worsened ranged from a low of 11% (Atlantic) to a high of 30% (Alberta).

| Province/Territory of Respondent |

Improved | Unchanged | Worsened | Not Sure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manitoba (n=16) | 50% | 25% | 12% | 13% |

| Alberta (n=20) | 45% | 25% | 30% | 0% |

| British Columbia (n=100) | 44% | 27% | 21% | 8% |

| Saskatchewan (n=24) | 42% | 33% | 25% | 0% |

| Atlantic (n=10) | 33% | 56% | 11% | 0% |

| Quebec (n=13) | 31% | 46% | 23% | 0% |

| Yukon (n=7) | 29% | 57% | 14% | 0% |

| Ontario (n=28) | 22% | 46% | 21% | 11% |

| Overall (n=217) | 41% | 32% | 21% | 6% |

| Source: Survey of Water System Operators, 2019 |

||||

WSOs were also asked whether they agreed or disagreed that their community's drinking water and wastewater services were to a level and quality of service comparable to that enjoyed by Canadians living in non-First Nations communities of similar size and location. As indicated in the following table, overall 76% of WSOs indicated that their community's drinking water services were comparable while only 51% of WSOs indicated that their wastewater services were comparable to that in non-First Nation communities. In all regions, the share of respondents that indicated their community's drinking water was comparable was higher than the share indicated for wastewater services.

| Province/Territory of Respondent |

Drinking Water | Wastewater | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = | Agree | Disagree | Not Sure | n = | Agree | Disagree | Not Sure | |

| Saskatchewan | 24 | 88% | 12% | 0% | 24 | 50% | 25% | 25% |

| Yukon | 7 | 86% | 14% | 0% | 7 | 57% | 29% | 14% |

| Quebec | 15 | 80% | 20% | 0% | 15 | 67% | 20% | 13% |

| Atlantic | 10 | 80% | 20% | 0% | 10 | 40% | 20% | 40% |

| British Columbia | 100 | 79% | 12% | 9% | 99 | 60% | 23% | 17% |

| Manitoba | 16 | 75% | 0% | 25% | 16 | 56% | 19% | 25% |

| Alberta | 20 | 65% | 20% | 15% | 20 | 35% | 45% | 20% |

| Ontario | 28 | 68% | 21% | 11% | 27 | 22% | 48% | 30% |

| Overall | 220 | 76% | 13% | 11% | 218 | 51% | 28% | 21% |

Source: Survey of Water System Operators, 2019 |

||||||||

5.2 Operations and Maintenance

The amount of funding provided to First Nations for operation and maintenance of water and wastewater systems is insufficient.

The CFMP provides operations and maintenance funding as a subsidy to assist First Nations in the delivery of community infrastructure services on-reserve. The policy for drinking water and wastewater systems is to provide 80% of the average cost required to operate and maintain equivalent off-reserve capital assets to generally acceptable standards. Unlike capital projects, O&M funding is not based on proposals submitted by First Nations, but is established annually through an internal formula-based system contained in CFMP's Cost Reference Manual. The formula is run automatically using the Integrated Capital Management System (ICMS) each year and is applied to all eligible on-reserve assets contained in the ICMS inventory.Footnote 17 Notwithstanding inflationary increases, the formula has been unchanged for nearly two decades and does not adequately reflect new technologies and escalating cost pressures such as the cost of electricity.

The federal government is aware of the problems associated with the funding formula. As stated in the 'Deep Dive' Summary Report into the issue, "insufficient Operating and Maintenance funding for drinking water systems is a huge challenge across First Nations communities" and was highlighted as a significant issue by every region and organization included in the research.Footnote 18 Key informants included in this evaluation echoed these concerns and indicated that in addition to the formula not accurately estimating 80% of water and wastewater operating costs, it falsely supposed that communities possess available funds for the remaining 20%. Inadequate O&M funding can impact the provision of water and wastewater services in several ways, including: low salaries for WSOs relative to nearby municipalities, which contributes to WSO turnover; a lack of back-up WSOs and WSOs-in-training; and, an inability to conduct proactive as opposed to reactive maintenance which leads to higher overall costs and reduces the length of time the infrastructure remains operational.Footnote 19

Some ISC regional offices have developed top-up programs that are meant to reduce the negative impacts resulting from the formula and Budget 2019 included additional funding to support O&M. However, it is premature to assess the impact of this funding over the short run as the negative impacts of insufficient funding are cumulative. Data organizations are working in collaboration with The Assembly of First Nations to study the issue and arrive at a more sustainable formula or approach for O&M funding.

Key informants indicate that the most sustainable way to address the issue of O&M funding is through an asset management approach and long-term funding agreements with First Nations. This approach involves describing what infrastructure is owned, what it is worth, its condition and remaining service life, when maintenance is required, how much operations, maintenance and replacement will cost and when those costs will occur, and the financial plans to ensure affordability in the long term.

5.3 Assessments

Annual Performance Inspections are carried out on nearly all water and wastewater systems. They provide high-level information about system risk but are limited in their ability to inform the prioritization of infrastructure projects. The last comprehensive assessment of water and wastewater systems was conducted during the period from 2009 to 2011.

The CFMP Program Manual indicates that Annual Performance Inspections (APIs) of First Nations water systems have been required since the introduction of the Protocol for Centralised Drinking Water Systems in First Nation Communities in 2006 and the Protocol for Centralised Wastewater Systems in First Nation Communities in 2010. The CFMP Program Manual indicates that APIs include site visits conducted by a qualified person (e.g. licensed consulting engineer, licensed Tribal Council engineer, provincial water systems inspector or a water system operator) who is certified to a level equivalent to the level of the system being inspected and is not a member of the band involved.Footnote 20 According to ISC, a total of 784 water APIs were completed in both 2016-17 and 2017-18, and a total of 511 wastewater APIs were competed in both 2016-17 and 2017-18.Footnote 21 It should be noted that APIs are not a measure of public health risk.

Key informants indicated that APIs provide a high-level overview that is helpful for determining which systems require more focused attention. While the APIs are the source of risk measurement available for systems, some key informants indicated that the approach is not easily understood due to the complexity of the API process and is less useful than a priorities-based approach.

As stated in the CFMP Program Manual, comprehensive assessments of water and wastewater systems serving First Nations are conducted periodically.Footnote 22 The most recent comprehensive assessment of water and wastewater infrastructure on-reserve was conducted between 2009 and 2011, during which consultants visited 571 participating First Nations communities to assess the condition of the water and wastewater assets, identified the capital and O&M needs and recommended future servicing options for the period 2010-2020.Footnote 23 Key informants indicated that another comprehensive assessment is now required to provide more accurate and up-to-date data for use by communities and ISC.

5.4 Climate Change

Climate change is likely to have a significant impact on source water as well as drinking water and wastewater infrastructure. To date, the response from the program has been primarily limited to reactive as opposed to proactive measures.

A 2008 AFN report describes the significant impact climate change could have on First Nations relationship with water throughout Canada and states that successful adaptation will require solutions that acknowledge and work with on-reserve water conditions. The report notes that impacts could include changes to seasonal water flow patterns; changes to precipitation patterns; warmer surface water temperatures; variations in surface water quantities; changes in surface water and groundwater levels and a higher incidence of drought, which together will result in widespread changes to water quality; and water availability and watershed vitality. Lower water levels eroding shorelines, unpredictable water movement and warmer water temperatures can impact water quality through a range of ways including increased erosion of exposed soils resulting in higher water turbidity levels, greater movement of pollutants into watercourses and larger quantities of solid matter requiring filtration, increased bacteria and fungi concentrations, increased summer phosphorus concentrations, and other effects.Footnote 24 Additionally, Health Canada has outlined several ways in which climate change could affect the health of communities, for example, by impacting water sources for food gathering, recreational and cultural use.

Overall, the report states that drinking water and wastewater treatment infrastructure will have to cope with filtering the degraded quality of water and will have to be designed and constructed to deal with everything from extreme weather to poorer water quality. Water infrastructure will need to withstand flooding in areas that have not historically been susceptible to floods and sewer systems may have to carry larger volumes of water than have been historically necessary as a result of heavy rains or quick spring ice-melt. Wastewater treatment must emphasize protection against breaches resulting in contamination from changes to 'normal' water levels as a result of climate change.Footnote 25

Key informants indicated that increased fires, floods and drought conditions have already affected source water and threatened infrastructure in First Nations communities. In addition, they stated that the extent to which potential climate change impacts are accounted for during infrastructure design and planning phases varies significantly based on the consultants involved in the program, and to date has been primarily reactive instead of proactive.

6. Findings: Environmental Public Health Program

6.1 Achievement of Outcomes

Performance targets related to monitoring drinking water quality are generally being achieved or significant progress has been made towards target values. The performance data shows that all communities have access to trained CBWMs or EPHOs to monitor drinking water quality. Most WSOs surveyed across Canada indicated that the frequency of testing their community's drinking water for quality is appropriate, and that their community members have confidence in their drinking water.

Monitoring bacteriological parameters in drinking water may be done by either an EPHO or a CBWM trained to conduct testing or through samples sent to accredited laboratories for analysis. According to the 2018 Performance Information Profile for the Water and Wastewater Program, the percentage of communities with access to trained CBWMs or EPHOs to monitor drinking water quality has met the target of 100%.Footnote 26

According to the GCDWQ, Public Water Systems (PWSs) should be sampled four times per month evenly spaced, for a total of 48 out of 52 weeks. To reflect regional realities and challenges in sampling PWSs four times per month (e.g. band office closures, holidays, staff turnover, etc.), eligible PWSs are considered to be in compliance with recommended sampling for bacteriological parameters if it is sampled 85% (44 out of 52 weeks each year).Footnote 27 The following table indicates the number of PWSs monitored weekly, monthly and not at all during the five year period from 2012-13 to 2016-17. According to key informants, the decrease in the share of PWSs monitored weekly from 64% in 2012-13 to 42% in 2014-15 was primarily a result of travel restrictions imposed by senior management which limited the number of community visits that could be done by EPHOs.Footnote 28

| Fiscal Year | PWSs Monitored Weekly | PWSs Monitored Monthly | PWSs not Monitored | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| 2012-13 | 413 | 64% | 151 | 22% | 11 | 2% |

| 2013-14 | 193 | 58% | 99 | 30% | 23 | 7% |

| 2014-15 | 145 | 42% | 52 | 15% | 13 | 4% |

| 2015-16 | 157 | 48% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| 2016-17 | 191 | 57% | 68 | 20% | 0 | 0% |

|

Source: FNIHB Drinking Water Program National Reports, 2012-13 through 2017-18 |

||||||

The method described above and presented in Table 4 considers a system to be compliant if the system was monitored 48 out of 52 weeks (or 44 weeks for eligible systems). If a system was monitored, for example, 47 weeks out of 52 instead of 48, it would be considered non-compliant and the 47 weeks of actual monitoring would not be recognized or tabulated. In an effort to improve the statistical analysis of bacteriological monitoring, Statistics Canada was enlisted to suggest a method that could better reflect the bacteriological monitoring taking place. They suggested an averaging method where the sampling frequency of each system is calculated based on the monitoring taking place and not a "pass vs. fail" method. For example, if a system was monitored 47 weeks out of 52 weeks, the system would be considered to have a sampling frequency of 98% (i.e. 47/48).Footnote 29 The following table reports the average sampling frequency for PWSs has increased from 75% in 2012-13 to 80% in 2016-17. According to the EPHP Performance Information Profile, the target value is 84% by March 2022.Footnote 30

| Metric | Actual Values | Target Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2021-22 | |

| Average Sampling Frequency | 75% | 78% | 79% | 80% | 80% | 84% |

Source: 'Actual Values' from FNIHB Drinking Water Program National Reports, 2013-14 through 2016-17; 'Target Value' from FNIHB EPHP PIP. |

||||||

As shown in the following table of survey results, most WSOs across all regions agreed that the frequency at which their community tests drinking water (verification monitoring) for quality is appropriate, with respondents from communities in Ontario (100%), Atlantic (100%), Quebec (93%) and Alberta (90%) most likely to have agreed. One-in-five (21%) respondents from Saskatchewan disagreed. Most WSOs indicated that there are a sufficient number of CBWMs in their community but based on survey responses, there may be demand for more CBWMs in certain regions where a higher share of respondents disagreed with the statement including Manitoba (33%), Atlantic (30%) and Saskatchewan (29%).

| Province/Territory of Respondent | "The frequency of testing drinking water for quality is appropriate" | "There are a sufficient number of CBWMs in the community" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Disagree | Not Sure | Agree | Disagree | Not Sure | |

| Ontario (n=27) | 100% | 0% | 0% | 74% | 19% | 7% |

| Atlantic (n=10) | 100% | 0% | 0% | 70% | 30% | 0% |

| Quebec (n=14) | 93% | 0% | 7% | 93% | 7% | 0% |

| Alberta (n=19) | 90% | 5% | 5% | 68% | 16% | 16% |

| Yukon (n=7) | 86% | 0% | 14% | 86% | 14% | 0% |

| British Columbia (n=98) | 83% | 8% | 9% | 72% | 21% | 7% |

| Manitoba (n=15) | 80% | 13% | 7% | 60% | 33% | 7% |

| Saskatchewan (n=24) | 71% | 21% | 8% | 71% | 29% | 0% |

| Overall (n=214) | 89% | 7% | 4% | 73% | 21% | 6% |

Source: Survey of Water System Operators, 2019 |

||||||

As indicated in the following table of survey results, 77% of all WSOs agreed that their community has confidence in its drinking water while 14% disagreed. The WSOs from communities in Saskatchewan (30%) and Atlantic (20%) were the most likely to disagree. WSOs were also asked if their community has the capacity to identify water quality problems and potential waterborne diseases. Overall, 80% of WSOs surveyed indicated they had such capacity and 11% indicated they did not. WSOs in Saskatchewan (25%) and Quebec (21%) were most likely to indicate that they lacked that capacity, most often because the community lacked the sufficient equipment to test water locally and must instead send samples away to an accredited lab for analysis.

| Province/Territory of Respondent | "The community has confidence in its drinking water" | "The community has capacity to identify water quality problems and potential waterborne diseases" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Disagree | Not Sure | Agree | Disagree | Not Sure | |

| Yukon (n=7) | 86% | 0% | 14% | 86% | 0% | 14% |

| British Columbia (n=98) | 82% | 10% | 8% | 83% | 8% | 9% |

| Atlantic (n=10) | 80% | 20% | 0% | 90% | 10% | 0% |

| Manitoba (n=15) | 80% | 13% | 7% | 80% | 7% | 13% |

| Ontario (n=26) | 73% | 15% | 12% | 85% | 11% | 4% |

| Quebec (n=14) | 72% | 14% | 14% | 64% | 21% | 14% |

| Alberta (n=19) | 68% | 16% | 16% | 68% | 16% | 16% |

| Saskatchewan (n=23) | 61% | 30% | 9% | 71% | 25% | 4% |

| Overall (n=214) | 77% | 30% | 9% | 80% | 11% | 9% |

Source: Survey of Water System Operators, 2019 |

||||||

6.2 Program Design and Delivery

The design of the EPHP is considered to be appropriate, although the overall workload of Environmental Public Health Officers continues to be an area of concern. Requests from communities, program fulfilment and emergency response all drive the activities undertaken by EPHOs, who because of the design of the program tend to have effective relationships within communities. Nearly half (45/108) of all EPHOs have been transferred to First Nations control.

Most key informants characterize the design of the EPHP as being very appropriate, despite being under-resourced. EPHOs spend much of their working time in communities and so tend to have effective relationships with community leadership, health and infrastructure managers, WSOs, and others. This element of the Program design is said to be a key strength and is consistent with the 2016 evaluation of ISC-FNIHB 's EPHP which found that the Program has demonstrated capacity to work effectively with First Nations communities to identify and to assess risks, and to provide recommendations with respect to addressing environmental risks. In addition, nearly half (45/108) of all EPHOs have been transferred to First Nations control, with ISC continuing to fund environmental health programs through grants and contributions.

Despite the Program's achievements, there have long been concerns raised about available resources for the Program. The Drinking Water Program Reports published by ISC-FNIHB from 2012-13 through 2016-17 states that "the current A-base and FNWWAP allocated FTE positions are insufficient to successfully deliver the program".

Water issues on reserves are a longstanding concern and have received multiple cycles of targeted investment to address specific issues since 2003. Since 1970, with the exception of drinking water, investments have not been made in EPHO capacity and associated resources.

In February 2018, the Deep Dive report estimated the shortfall of Environmental Public Health Officers to be 54 FTEs.Note de bas de page 31 Findings from key informant interviews reinforce the perception that there is a long-standing deficiency in the total number of Environmental Health Officers providing service to First Nations communities.Note de bas de page 32 The level of demand for EPHO services has increased over time due to limited A-base funding in Regions, population growth in communities, and large infrastructure investments made within communities. The extent to which each of these pressures impacts the provision of EPH services to First Nations communities are subject to variation due to factors such as region, remoteness, community capacity and others.

Key informants also revealed that the EPHP appears to be very reliant on the funding it receives for water and wastewater, despite these being just two of eight Program areas. Notwithstanding emergency issues that arise, the ability to focus on other EPH Program areas in a proactive and timely manner is said to be limited by the clear direction to focus on the Drinking Water Program from the priority placed on eliminating LT-DWAs by the federal government.

7. Findings: Training and Capacity Development

7.1 Water System Operators

Departmental data shows that not all primary WSOs are certified to the level of the water and/or wastewater system in their communities; however, training is on-going. Key informants indicated that there are several barriers to obtaining a sufficient number of trained WSOs, including a lack of funding for back-up WSOs, and turnover due to certified WSOs moving to higher paid jobs outside of their communities. In addition, most communities lack a succession plan for WSOs.

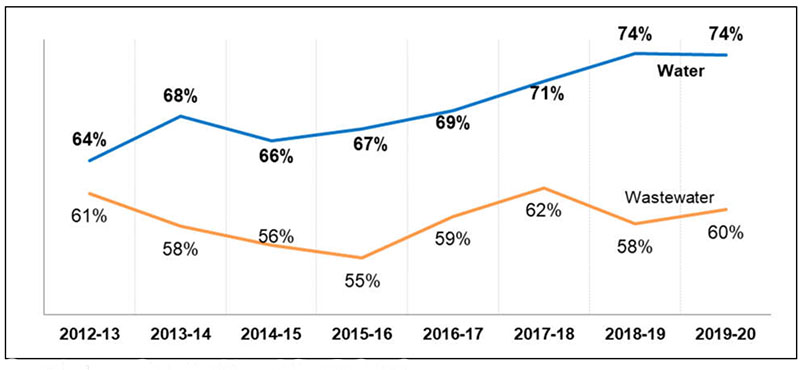

As shown in Figure 4, the percentage of public water systems that have primary WSOs certified to the level of the system in their communities increased from 64% in 2012-13 to 74% in 2019-20. For wastewater systems, the rate has fluctuated over the eight-year time period shown in the figure; however, the value in 2019-20 (60%) is similar to the value in 2012-13 (61%). The Departmental Results Reports do not state a target value for this indicator. It appears that adequate opportunities for certification training are available, but other factors limit overall certification rates including WSO turnover and lack of back-up WSOs, as well as community remoteness and other barriers to advanced education.

Figure 3: Percentage of Public Water Systems and Public Wastewater Systems that have Primary Water System Operators Certified to the level of the System

Source: Data provided by ISC Strategic Water Management Team.

Text alternative for Figure 3: Percentage of Public Water Systems and Public Wastewater Systems that have Primary Water System Operators Certified to the level of the System

Figure 3 is a line chart illustrating the percentage of public water systems and public wastewater systems that have primary water system operators certified to the level of the system that they run.

In 2012-2013, 64% of public water systems had operators certified to the level of the water system that they run. 61% of public wastewater systems that had operators certified to the level of the wastewater system that they run.

In 2013-2014, 68% of public water systems had operators certified to the level of the water system that they run. 58% of public wastewater systems that had operators certified to the level of the wastewater system that they run.

In 2014-2015, 66% of public water systems had operators certified to the level of the water system that they run. 56% of public wastewater systems that had operators certified to the level of the wastewater system that they run.

In 2015-2016, 67% of public water systems had operators certified to the level of the water system that they run. 55% of public wastewater systems that had operators certified to the level of the wastewater system that they run.

In 2016-2017, 69% of public water systems had operators certified to the level of the water system that they run. 59% of public wastewater systems that had operators certified to the level of the wastewater system that they run.