Evaluation of the Post-Secondary Education Program

October 2020

PDF Version (595 KB, 34 Pages)

Table of contents

List of Acronyms

| CCOE |

Chief Committee on Education |

|---|---|

| CIRNAC |

Crown Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada |

| CSL |

Canada Student Loan |

| ESDC |

Employment and Social Development Canada |

| ESDPP |

Education and Social Development Programs and Partnership |

| ERAS |

Education Reporting and Analysis Solution |

| ISC |

Indigenous Services Canada |

| MC |

Memorandum to Cabinet |

| OAG |

Office of the Auditor General of Canada |

| PSE |

Post-Secondary Education |

| PSPP |

Post-Secondary Partnerships Program |

| PSSSP |

Post-Secondary Student Support Program |

| TB |

Treasury Board |

| UCEPP |

University College Entrance Preparation Program |

Preamble

This evaluation covers the period between 2012 and 2018. It is important to note that near the end of the evaluation period, transformative policy and program changes were developed and are currently being implemented. For example, in 2018-19, funding for the program included $387.4 million for the Post-Secondary Student Support Program; $22.2 million for the Post-Secondary Partnerships Program; and $5.8 million for Indspire. Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), in collaboration with Employment and Social Development Canada, has completed a review of federal support for Indigenous post-secondary education to help ISC and its partners to advance distinctions-based post-secondary education strategies.

Taking into consideration the timing of this evaluation, its findings and its recommendations, the evaluation will support the Department in activities leading to new approaches related to Post-Secondary Education. For example, and as directed by the December 2019 mandate letter for Minister of Indigenous Services Canada, the Department is ensuring that First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation students have the support they need to access and succeed at post-secondary education.

Independent of this evaluation, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) released a performance audit in the spring of 2018 titled, "Socio-economic Gaps on First Nations Reserves – Indigenous Services CanadaFootnote 1." In addition to examining progress made on closing socio-economic gaps between First Nations people on reserve and non-Indigenous Canadians, the report also examined the use of data by ISC's education programsFootnote 2.

While different in scope, the program's response to both the OAG's report and the evaluation's findings includes taking an effective long-term approach that meets the needs of First Nations, Métis and Inuit partners. For example, the recommendations provided in this evaluation are part of the approach to support the Post-Secondary Education of First Nations. Through Budget 2019, ISC has made investments over five years to renew and expand funding for First Nations students. Budget 2019 has also made investments for new distinctions-based Indigenous post-secondary education strategies to support the new Inuit and Métis Nation post-secondary education strategies. The implementation of Budget 2019's post-secondary education funding has been designed specifically through engagement with the respective National Indigenous Organizations. This effort includes the co-development of Terms and Conditions, National Program Guidelines, and Results Frameworks. First Nations are also currently undertaking three years of regional engagement toward the development of integrated First Nations regional post-secondary education models, as part of the effort towards devolution of First Nations programming.

Executive Summary

ISC's support for post-secondary education is comprised of four key programs: the Post-Secondary Student Success Program (PSSSP); the University College Entrance Preparation Program (UCEPP); the Post-Secondary Partnerships Program (PSPP); and, Indspire.

The PSSSP has enabled many Indigenous students to access post-secondary education, where the vast majority are successful in any given academic year. However, while ISC's role as a funding agent is appropriate, its fundamental purpose in the context of post-secondary education is unclear. The program's goal is to enable access to post-secondary education, yet it does not measure the extent to which it enables that access relative to demand. Conversely it has little to no influence over the academic success of supported students, yet it tracks their academic progress.

Part of the suite of tuition subsidies supported by ISC's band-support funding for post-secondary education includes the UCEPP. This program provides financial support for students who do not quite meet the eligibility requirements for a standard academic program but may be eligible for a transitional year to upgrade their academic skills. Ultimately, the success rate is low for these students, with only a fifth progressing to a program of study in any given year. Participants in this evaluation concluded that a tuition subsidy for an academic upgrading program alone misses a great need to support students on the cusp of being able to enroll in an academic program, and that more transitional and institutional supports are needed.

ISC does provide some support for non-academic, transition-type initiatives through the PSPP; however, this program is more geared toward the development of Indigenous academic programs and the Indigenization of academic institutions. The proposal-based model was generally identified as problematic and out of sync with the priority to assist students with general support and transition. Incentivizing post-secondary institutions to develop Indigenous studies courses is essential but should also complement a larger suite of transitional support programs. Organisations that have sought PSPP funding have also indicated that there are no available examples of successful proposals to consult, and that the department does not communicate back to applicants about why proposals have been rejected.

The final element of Indigenous-specific post-secondary supports funded by ISC is Indspire, which is seen as a successful program in promoting and celebrating the success of Indigenous peoples and supporting high-achieving individuals who need financial support. Its reach is expanding, and it has been lauded for its successes and inspiration; however, one major gap is that Indspire does not provide documents or offer services in French.

The missing policy piece when it comes to ISC's post-secondary support is with respect to the completion of secondary studies by adult learners. As a matter of policy, learners over 21 are not covered under ISC's elementary/secondary education funding, nor is there a policy provision for this in post-secondary support. Given that it is unreasonable to expect adult learners to complete secondary studies with younger peers in the secondary system, a policy provision for this group within the context of post-secondary education is needed, including consideration of the expansion of PSSSP or UCEPP to include secondary studies completion, or a new adult learning program designed to ensure all prospective adult learners have sufficient support to complete secondary.

Looking only at the population of children on reserve, if most or all students were completing secondary, we would expect there to be approximately 7,000 graduates per year from this group. In reality there are only about 3,000 per year and consequently a majority of First Nations are largely excluded from post-secondary opportunities and most of the labour force in general. This does not include Inuit and other Indigenous persons who are band members but not on the Nominal Roll on reserve. The result is a vast under-representation of First Nations and Inuit peoples in the labour force and resultant disproportionate poverty and social and economic exclusion.

Therefore, it is recommended that ISC:

- Work with First Nation and Inuit partners, and consult with Employment and Social Development Canada and other departments or ministries and academic institutions, to develop a strategy to provide more equitable access to post-secondary funding supports for all prospective First Nation and Inuit students;

- Work with First Nation partners to develop a clear policy for adult learners to complete secondary studies and boost eligibility for post-secondary and labour-market entry;

- Work with First Nation and Inuit partners to develop a strategy to support students who wish to pursue post-secondary studies – whether they are transitioning into post-secondary and need to complete secondary or upgrade, or whether they are attending post-secondary and need support to stay in school – beyond tuition through enhanced, culturally appropriate wrap-around supports;

- Work with First Nation and Inuit partners to develop a measurement strategy to assess demand for post-secondary funding supports, the needs of eligible learners, and the impact of federal funding in addressing the needs of eligible learners (i.e. differentiated from other funding sources at the band level); and,

- Broaden the PSPP to include more non-academic and transitional supports, and improve communications with prospective funding recipients to ensure clarity and transparency in funding decisions.

Management Response and Action Plan

Evaluation Title: Evaluation of the Post-Secondary Education Program

1. Overall Management Response

Overview

- This Management Response and Action Plan was developed to address recommendations resulting from the Evaluation of the Post-Secondary Education Program, which was conducted by the Evaluation and Policy Redesign Branch. The evaluation covers the period between 2012 and 2018. It examines the impacts of the Post-Secondary Student Success Program (PSSSP), the University and College Entrance Preparation Program (UCEPP), the Post-Secondary Partnerships Program (PSPP), and Indspire, representing approximately $335 million per year between 2013-14 and 2016-17.

- The evaluation provided five recommendations to improve the Post-Secondary Education Program. All recommendations are accepted by the program and the attached Action Plan identifies specific activities by which to address these. The recommendations speak to working with Indigenous partners to advance post-secondary education priorities for Indigenous students. In particular, recommendations # 1, 3 and # 5 speak to the development of a strategy to provide additional funding supports for First Nations and Inuit post-secondary education. Overall, the recommendations involve working internally with the relevant ISC sectors, externally with other federal departments and with First Nations and Inuit partners to ensure processes more effectively support First Nations and Inuit Post-Secondary Education. Further to this evaluation, a Métis Nation Post-Secondary Education strategy has also been developed and ongoing engagement is occurring with Métis partners.

- This evaluation was conducted in time for consideration of program renewal. The timing of this evaluation and the recommendations will support the Department in activities leading to new approaches related to Post-Secondary Education. For example, and as directed by the December 2019 mandate letter for Minister of Indigenous Services Canada, the Department is ensuring that First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation students have the support they need to access and succeed at post-secondary education.

- An effective long-term approach will be one that meets the needs of First Nations, Métis and Inuit partners. The recommendations provided in this evaluation are part of the approach to support the Post-Secondary Education of First Nations. Through Budget 2019, ISC has made investments over five years to renew and expand funding for First Nations students. Budget 2019 has also made investments for new distinctions-based Indigenous post-secondary education strategies to support the new Inuit and Métis Nation post-secondary education strategies. The implementation of Budget 2019's post-secondary education funding has been designed specifically through engagement with the respective National Indigenous Organizations. This effort includes the co-development of Terms and Conditions, National Program Guidelines, and Results Frameworks. First Nations are also currently undertaking three years of regional engagement toward the development of integrated First Nations regional post-secondary education models, as part of the effort towards devolution of First Nations programming.

Assurance

- The Action Plan presents appropriate and realistic measures to address the evaluation's recommendations, as well as timelines for initiating and completing the actions.

2. Action Plan Matrix

| Recommendations | Planned Action(s) | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start/ Completion Dates and Additional Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work with First Nation and Inuit partners, and consult with Employment and Social Development Canada and other departments or ministries and academic institutions, to develop a strategy to provide more equitable access to post-secondary funding supports for all prospective First Nation and Inuit students. | We do concur. |

Assistant Deputy-Minister (Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) Director General (Education Branch, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) |

Start Date: 2017 Completion Date: March 2022 a) A review of post-secondary education for Indigenous students was carried out in 2017-18 to 2018-19 that included engagement and outreach activities with Indigenous stakeholders and with support by ESDC. A need for distinction-based post-secondary education strategies resulted from the review. Budget 2019 was informed by the review results and policy proposals submitted by each of the three First Nations, Inuit and Metis Nation National Organizations, in which all three called for support to:

Budget 2019 made investments over five years for First Nations students and a 10 year funding line for ramp up and an ongoing amount to support the new Inuit and Métis Nation post-secondary education strategies. In addition, the Terms and Conditions of existing programs were amended. First Nations are also currently undertaking three years of regional engagement toward the development of integrated First Nations regional post-secondary education models as part of the effort towards devolution of First Nations programming. More funding is being directed to PSE through Budget 2019 investments. Post-Secondary StudentSupport Program (PSSSP) funding received is no longer counted as a student resource or 'income' in Canada Student Loan applications therefore Indigenous students are likely to qualify for more funding under CSL to support their post-secondary studies. As well, five years of additional funds were invested to help give First Nations students same opportunities for success as non-Indigenous students. |

| a) ISC will work with First Nations, Inuit, Employment and Social Development Canada and other departments to develop and implement a strategy to provide more equitable access to post-secondary funding supports for all prospective First Nation and Inuit students. | |||

| 2. Work with First Nation and Inuit partners to develop a clear policy for adult learners to complete secondary studies to boost eligibility for post-secondary and labour-market entry. | We do concur. |

Assistant Deputy-Minister (Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) Director General (Education Branch, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) |

Start Date: 2020 Completion Date: March 2022 a) ESDPP is further examining the complexities related to Adult Education in relation to the transformative change underway within the Education programming as a whole. Given the work underway both within the K-12 system to move towards First Nations control of First Nations education, as well as the review and enhancements of the broader PSE portfolio in Budget 2019, the examination of adult education is a part of current planning to explore programmatic options. This work includes the establishment of regular bilateral meetings with both First Nations and Inuit partners respectively to identify joint priorities, gaps and needs in Fall 2020. |

| a) ISC will work with First Nations and Inuit partners to develop a clear policy for adult learners. | |||

| 3. Work with First Nation and Inuit partners to develop a strategy to fund students who wish to pursue post-secondary studies—whether they are transitioning into post-secondary and need to complete secondary or upgrade, or whether they are attending post-secondary and need support to stay in school—beyond tuition through enhanced, culturally appropriate wrap-around supports. | We do concur |

Assistant Deputy-Minister (Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) Director General (Education Branch, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) |

Start Date: 2020 Completion Date: March 2022 a) With funding provided in Budget 2019, ISC launched new distinctions-based post-secondary education strategies in 2019-20. As part of these strategies, Indigenous post-secondary students are provided funding to support expenses including tuition and other student fees, living expenses, including for dependents if applicable, and wrap-around services, such as expenses associated with travel home, supplemental tutorial, guidance and counseling services and child care, as needed. Post-Secondary Partnerships Program (PSPP) funding has been redirected to First Nations communities and First Nations-established institutions to help concentrate resources towards culturally appropriate program delivery and to better meet students' needs, including the use of Elders and culturally based counseling. For example, the First Nations University delivers lands-based education, like social work and education culture camps. This type of approach to academic delivery, partnership and capacity building (they use local Elders and sessional instructors) and the integration of Indigenous worldview in all their programming is just one of the reasons why they have seen their number of students more than double in 2020-21 compared to 2016-17. New funding through the Inuit and Métis Nation PSE strategies includes provision for complementary and culturally appropriate wrap-around services for Inuit and Métis Nation students. |

a) ISC will work with First Nations and Inuit partners to develop a strategy to fund students who wish to pursue post-secondary studies, as identified by the recommendation. |

|||

| 4. Work with First Nation and Inuit partners to develop a measurement strategy to adequately assess demand for post-secondary funding supports, the needs of eligible learners, and the impact of federal funding in addressing the needs of eligible learners (i.e. differentiated from other funding sources at the band level). | We do concur. |

Assistant Deputy-Minister (Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) Director General (Education Branch, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) |

Start Date: 2018 Completion Date: March 2022 a) Through the Permanent Bilateral Mechanisms, ISC and Inuit leaders jointly endorsed priorities on post-secondary education in June 2018. ISC also signed a historic Post-Secondary Education Sub-Accord with the Métis Nation in June 2019. With funding provided in Budget 2019, ISC launched new distinctions-based post-secondary education strategies in 2019-20 that include: direct financial assistance to Inuit and Métis Nation students for post-secondary education (tuition, supplies, accommodation and travel); complementary programs and services (academic readiness, cultural support and life-skills development); and, educational governance support (funding to support service delivery and track post-secondary data). ISC developed performance indicators for the distinction-based PSE Strategies with input from partners to measure the demand and needs for post-secondary funding supports. The following performance indicator was included in the First Nation, Métis Nation and Inuit PSE Strategies to assess demand and needs for PSE: "Percentage of eligible students who applied and received funding for post-secondary education." The target for this indicator for First Nations is 80%-85% of students by 2022-2023. Targets for Métis Nation and Inuit students will be developed in collaboration with partners.The department is also working on improving our data collection from our programs, including additional mechanisms to collect data and report on the demand for post-secondary funding. Recipients are responsible for completing an annual report and for submitting it to their ISC representative by June 30 (Inuit) August 31 (Metis Nation) and at a date to be determined for PSSSP the year following receipt of funds. The report includes information on indicators listed in the terms and conditions. Additionally, First Nations are currently conducting engagements to develop long-term First Nations regional PSE models. These conversations will also cover development of robust and relevant performance indicators and reporting requirements that balance the Department's need for information while minimizing the reporting burden on partners. |

|

a) ISC will put together and begin to implement a work plan that will produce an approach to measuring the demand for post-secondary funding in a comprehensive needs-based manner. |

|||

| 5. Broaden the PSPP to include more non-academic and transitional supports, and improve communications with prospective funding recipients to ensure clarity and transparency in funding decisions. | We do concur. |

Assistant Deputy-Minister (Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) Director General (Education Branch, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) |

Start Date: 2020 Completion Date: March 2022 PSPP is being transformed to better meet needs of First Nations students and lead towards devolution: a) First Nations: Eligibility criteria for funding recipients under PSPP was changed in 2020-2021 to direct funding to First Nations-established post-secondary education institutions and First Nation community-based programming as a way to respect the principle of First Nation control of First Nation education, and to allow the PSPP to support First Nations to develop their own partnerships with post-secondary institutions to increase the availability of post-secondary education programs tailored to their unique cultural and educational needs. PSPP funding provides support which can allow First Nations to develop and deliver post-secondary education programming for First Nations students that leads to the attainment of a post-secondary education credential. First Nations will also receive funding over three years, starting in 2019-20 to support regional engagement for the purpose of developing integrated, regional First Nation post-secondary education models. Under the Inuit and Métis Nation post-secondary education strategies, which derived from the MC and TB submission, funding is made available to support wrap-around services and build institutional capacity in order to encourage better retention and attainment rates. |

|

ISC will work with partners to: a) Broaden the PSPP to include more non-academic and transitional supports. |

|||

We do concur. |

Assistant Deputy-Minister (Education and Social Development Programs and Partnership) Director General (Education Branch, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships) |

Start Date: 2019 Completion Date: March 2020 b) The reform of the PSPP (outlined above) was done with First Nations partners, to better allow First Nations control over First Nations education and funding decisions. Funding is delivered regionally to allow for enhanced communications and transparency. In addition, the PSPP regional allocation for 2020-21 was supported by the Assembly of First Nations Chiefs Committee on Education (CCOE). |

|

b) Enhance communications to make funding more transparent |

1. Introduction

Since the creation of the new departments of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) in November 2017, Post-Secondary Education now falls under the mandate of ISC.

The Evaluation of the Post-Secondary Education program was undertaken in 2017-2018, and generally examined activities and progress against stated departmental outcomes covering the period from 2012-13 to 2017-18. The evaluation included a series of eight site visits in most regions in Canada (except Yukon and Atlantic), as well as 71 key-informant interviews with First Nation education administrators, ISC staff, provincial education representatives, post-secondary institutions and stakeholder groups. Additionally, a full analysis of the contents of the Education Reporting and Analysis Solution (ERAS) database, as well as an extensive literature review, was undertaken.

Gender based analysis+ is embedded throughout the report; in collecting and analyzing data, factors including gender, age, mental health and cultural identity were considered.

Much of this evaluation was undertaken while the Government of Canada was engaging First Nations and other Indigenous communities on education funding reform, through 2017 and 2018. In order to avoid duplication and overlap of efforts, the evaluation scope and depth were reduced so as not to seek the same information from the same groups, and to provide a perspective after reflecting on some of the outputs of those engagements.

Independent of this evaluation, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada released a performance audit in the spring of 2018 titled, "Socio-economic Gaps on First Nations Reserves – Indigenous Services CanadaFootnote 3." In addition to examining progress made on closing socio-economic gaps between First Nations people on reserve and non-Indigenous Canadians, the report also examined the use of data by ISC's education programsFootnote 4. The report raised significant concerns with the Department's measurement, collection, use, sharing of, and reporting on First Nations' education data and results, as well as the lack of data about post-secondary graduation rates, demand for post-secondary support, and the impacts of federal funding on students' academic success.

The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Accounts is overseeing the implementation of three recommendations relating to ongoing progress on the development of socio-economic gap measures; regional educational agreements; and adjustments to the Department's Education Information SystemFootnote 5. Many of this evaluation's findings mirror those of the OAG report. Where appropriate, this report therefore makes note of the Auditor General's findings.

This evaluation specifically examined the impacts of the Post-Secondary Student Success Program (PSSSP), the University and College Entrance Preparation Program (UCEPP), the Post-Secondary Partnerships Program (PSPP), and Indspire.

2. Program Description

The Government of Canada provides financial support for First Nation students and eligible Inuit students for post-secondary education, and provides support to Canadian post-secondary institutions for the design and delivery of university- and college-level courses that respond to the education needs of First Nation and Inuit students. ISC's post-secondary education funding is intended to support eligible students to offset tuition, travel costs, living costs and other expenses.

Respecting the principle of First Nations control of First Nations education, First Nations, and organizations designated by First Nations, are responsible for managing and delivering education programs and services for students who are ordinarily living on reserve.

Annual funding for post-secondary programs was around $335 million between 2013-14 and 2016-17. Budget 2017 announced a comprehensive and collaborative review of federal support for post-secondary education for Indigenous learners. The Department was engaging partners and stakeholders to gather information regarding what works well and what requires attention, in order to develop forward-looking, student-centered recommendations. The scope of consequential change could extend from program adjustments to redesign.

2.1 Post-Secondary Student Success Program (PSSSP) and the University and College Entrance Preparation Program (UCEPP)

The PSSSP provides financial assistance to First Nation students and eligible Inuit students enrolled in eligible post-secondary programs. UCEPP provides financial assistance to First Nation students and eligible Inuit students enrolled in university or college entrance programs to help them gain the academic level required to enter a degree or diploma program.

The objective of the PSSSP is to improve the employability of First Nation students and eligible Inuit students by providing them with funding to access education and skills development opportunities at the post-secondary level. This is with a view to increasing post-secondary enrollment and graduation rates among First Nation and Inuit students. The objective of the UCEPP is to provide financial support to eligible First Nation students and Inuit students who are enrolled in university and college entrance preparation programs offered in Canadian post-secondary institutions, to enable them to attain the academic level required for entrance into degree and diploma credit programs. This is with a view to increasing the number of First Nation students and Inuit students with the requisite academic level for entrance into post-secondary programs.

Funding is made available to band councils of recognized First Nation bands (who may also administer the program for eligible Inuit students); their designated organisations; and self-governing First Nations in Yukon that have not yet assumed responsibility for Post-Secondary Education through a Programs and Services Transfer Agreement or through the terms of their self-government agreement. These funding recipients can make funds available to eligible students who are enrolled in eligible institutions and for eligible programs.

The Band Council or designate may set their own priority process within the National Guidelines. The funds can cover, but are not limited to, tuition fees; examination fees; books and supplies; living allowances for full-time students commensurate up to the level allowed by the Canada Student Loans Program; and other costs, up to a maximum of $50,000 per student per year (during the evaluation period), within the recipient's budget envelope for Post-Secondary Student Support.

The outcome, as outlined in the former INAC 2016-17 Report on Plans and Priorities and the 2017-18 Departmental Plan, is that First Nation and Inuit students who receive funding through the PSSSP progress in their program of study. This is measured by the percentage of PSSSP-funded students who completed their academic year and were funded the next academic year and the percentage of those students who continue in the program beyond the first year of their program of study. This outcome was revised from the 2015-16 Report on Plans and Priorities, which was that First Nation and Inuit post-secondary students progress in their programs of study. In 2014-15, it also included an outcome that First Nations and Inuit students participate in post-secondary education.

2.2 Post-Secondary Partnerships Program (PSPP)

At the time of this evaluation, the PSPP provided funding to eligible Canadian post-secondary institutions to design and deliver university- and college-level courses tailored for First Nation students and eligible Inuit students. These courses are intended to help students gain the skills they need to enter and succeed in the labour market.

It is a proposal-based program that supports projects that deliver a program of study or develop new courses and programs tailored for First Nation and Inuit students. In calls for proposals, priority is given to proposals that:

- focus on the labour market, with specific outcomes and objectives;

- lead to high-demand jobs in the Canadian economy or within First Nation or Inuit communities (such as governance);

- respond to the educational needs of First Nation and Inuit students;

- use innovative and efficient delivery methods to increase the availability of education in remote communities;

- have a plan towards financial self-sustainability;

- contain short-duration, undergraduate-level courses; and

- include funding partners with a firm commitment to monetary participation.

2.3 Indspire

Indspire is an Indigenous-led charity, where ISC provides funds to offer scholarships and bursaries to Indigenous students to pursue post-secondary education. Indspire also honours the achievements of Indigenous peoples; holds career fairs targeted at Indigenous youth from grades to 10 to 12; and develops, produces and disseminates curricula and other materials designed to inspire First Nation and Inuit high school students to consider career options in industries forecasted to have skilled labour shortages. Eligible costs for funding can include salaries; professional development; professional services; honoraria; facility rental; hospitality; scholarships and bursaries; awards; printing and publishing costs; materials; and, administration. Indspire will be funded by Employment and Social Development Canada in 2020-21.

2.4 Other Programs Related to Post-Secondary (not covered in this evaluation)

The First Nations and Inuit Youth Employment Strategy (being evaluated separately by Employment and Social Development Canada) provides youth with employment opportunities where they can gain work experience and develop important skills such as communication, problem-solving and teamwork. Summer work placements are intended to enable First Nation and Inuit students to learn about career options and to earn income that may contribute to university or college education.

The First Nations and Inuit Skills Link Program is one of two programs that ISC administers under the First Nations and Inuit Youth Employment Strategy. The objective is to promote the benefits of education as key to youth participation in the labour market; to support the development and enhancement of young people's essential employability skills, such as communication, problem solving and working with others; to introduce youth to a variety of career options; to help youth acquire skills by providing wage subsidies for mentored work experience; and to support mentored school-based work and study opportunities (co-operative education and internship).

The key activities of First Nations and Inuit Skills Link Program are: wage subsidies for work placements and mentorship for youth who are not in school to enable them to develop employability skills and support their educational and career development; activities designed to help First Nation and Inuit youth entrepreneurs gain skills towards self-employment; training experiences that support youth to acquire the necessary skills for work placements; career development information, including awareness and support activities like career fairs and leadership projects; career planning and counselling activities; and activities that promote science and technology as an educational and/or career choice, including science camps, computer clubs, and activities that connect science and technology to traditional Indigenous knowledge.

The First Nations and Inuit Summer Work Experience Program provides youth with opportunities for summer employment so that they can gain work experience and develop or enhance essential employability skills, including critical skills needed in the workplace such as communication, problem solving and teamwork. In addition, these summer work placements allow youth to learn about career options and to earn income that may contribute to university or college education.

3. Key Findings

3.1 Success of students supported through PSSSP

Finding 1: Post-Secondary students who are funded through PSSSP are achieving high rates of success, as measured by progression or graduation.

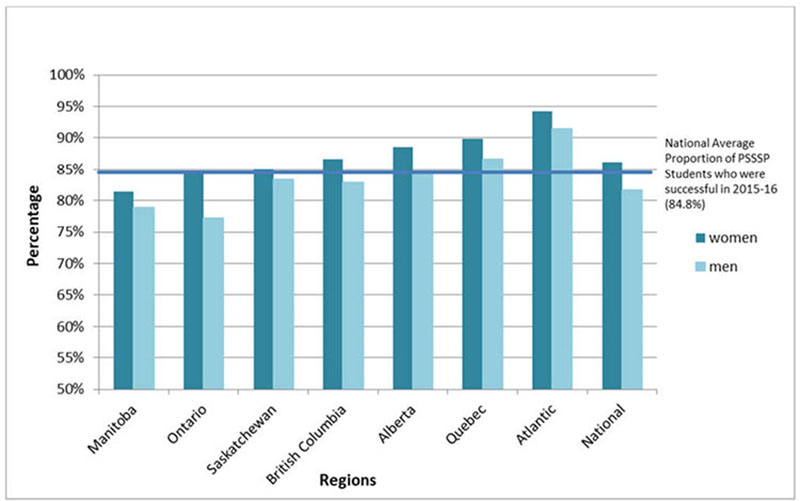

Data available (only complete to 2015-16 as of this writing) on post-secondary students supported by PSSSP does not allow for a longitudinal analysis of progression through studies. However, it does indicate whether a student does or does not successfully complete an academic year, and if they graduate. A graduation rateFootnote 6, however, is not possible because there is no indication of eligibility to graduate in any given semester (thus no denominator). Since 2012-13, the annual rate of success (completing the semester in satisfactory academic standing or graduating) for post-secondary students funded through PSSSP has been steady at approximately 84 percent of PSSSP-supported students in a given year. There is a small but notable gender difference with the success rate of women at approximately 85 percent, compared to approximately 82 percent for men (generally consistent between 2012-13 and 2015-16). The gender difference was generally consistent between regions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proportion of Women and Men by Region who were successful (progressed in satisfactory standing or graduated) in 2015-16*

*Note that standalone bars were not included for the Territories (Yukon, Nunavut and Northwest Territories) as they represent a very small proportion of overall students (0.3% of students in 2015-2016). National averages do include the Territories.

Text alternative for Figure 1: Proportion of Women and Men by Region who were successful (progressed in satisfactory standing or graduated) in 2015-16*

Figure 1 is a bar chart illustrating the proportion of female and male students enrolled in the Post-Secondary Student Support Program (PSSSP), by region and nationally, who were successful in 2015-2016. In this case, the term 'successful’ is defined as students who "progressed in satisfactory standing or who graduated". Also highlighted is the national average of PSSSP students who were successful in 2015-2016 which was 84.8%.

For students in the Manitoba region, 81.4% of women were successful, and 78.9% of men were successful.

For students in the Ontario region, 84.6% of women were successful, and 77.2% of men were successful.

For students in the Saskatchewan region, 85% of women were successful, and 83.4% of men were successful.

For students in the British Columbia region, 86.6% of women were successful, and 82.9% of men were successful.

For students in the Alberta region, 88.5% of women were successful, and 84.7% of men were successful.

For students in the Quebec region, 89.9% of women were successful, and 86.6% of men were successful.

For students in the Atlantic region, 94.2% of women were successful, and 91.5% of men were successful.

For students nationally, 86.1% of women were successful, and 81.7% of men were successful.

In general terms, it is not possible to attribute academic successes for these students to any specific support program. Notably, employment rates did not improve over this time frame, and actually decreased somewhat for Indigenous women and for First Nations overall.Footnote 7

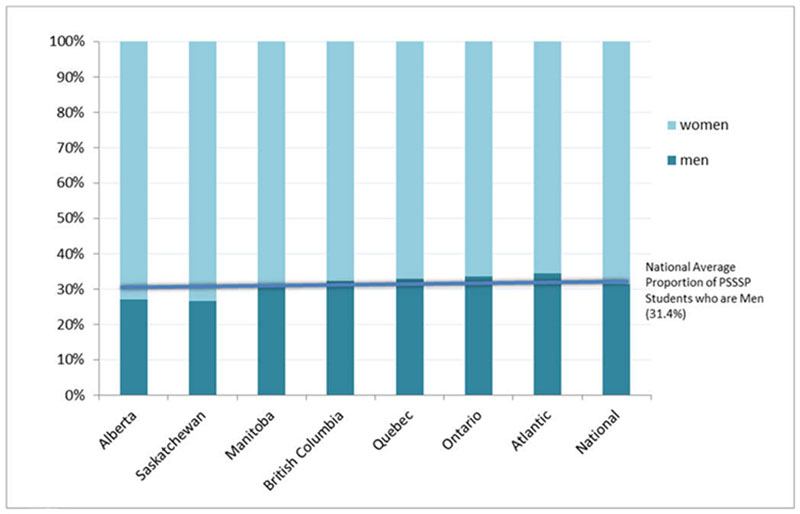

The number of students funded through PSSSP has remained relatively steady over this same time period (varying between approximately 23,000 and 24,500 per year), indicating an ongoing demand for this program. Importantly, there is a considerable gender difference in enrollment, with only approximately one third of enrollees being men (this has been somewhat stable at approximately 30 percent every year). According to national data on elementary/secondary completion, First Nation women graduate high school on average at a rate of 10 percent higher than First Nation men. As these post-secondary data show, this gender difference inflates significantly when examining First Nation learners funded through PSSSP. As shown in Figure 2, looking at 2015-16 figures, there was only a slight regional variation in this gender difference.

Figure 2: Proportion of PSSSP enrollees in 2015-16 by gender and by region*

*Note that standalone bars were not included for the Territories (Yukon, Nunavut and Northwest Territories) as they represent a very small proportion of overall students (0.3% of students in 2015-2016). National averages do include the Territories.

Text alternative for Figure 2: Proportion of PSSSP enrollees in 2015-16 by gender and by region*

Figure 2 is a stacked column graph illustrating the proportion of Post-Secondary Student Support Program (PSSSP) students by gender, by region and nationally in 2015-2016. Highlighted is the national average of PSSSP students who are men, which was 31.4%.

In the Alberta region the proportion of PSSSP students was 72.8% for women and 27.2% for men.

In the Saskatchewan region the proportion of PSSSP students was 73.2% for women and 26.8% for men.

In the Manitoba region the proportion of PSSSP students was 68.5% for women and 31.5% for men.

In the British Columbia region the proportion of PSSSP students was 67.8% for women and 32.2% for men.

In the Quebec region the proportion of PSSSP students was 67% for women and 33% for men.

In the Ontario region the proportion of PSSSP students was 66.4% for women and 33.6% for men.

In the Atlantic region the proportion of PSSSP students was 65.5% for women and 34.5% for men.

Nationally, the proportion of PSSSP students was 68.6% for women and 31.4% for men.

Indigenous partners confirmed that there is a high demand for funding amongst community members. They also suggested that academic success is not the only desired outcome for post-secondary students from their communities. The wellbeing of their students is a main focus, with an emphasis on emotional, mental and spiritual health as well as a sense of cultural belonging and identity. Indigenous students have identified general goals in other studies, which strengthen ties to their cultural identity, their ability to find their personal gifts or strengths, and emphasizing reciprocity over competitiveness with other students.Footnote 8 Some interviewees felt that the way outcomes are articulated overemphasized the importance of academic success as an indicator of overall success, as opposed to wellbeing.

The departmental desired outcome for the PSSSP for the last year of the period of study for this evaluation (2017-18) was that First Nation and Inuit post-secondary students who receive funding progress in their program of study. This was measured by assessing the number of students completing an academic year and being funded the following year, and by the number of students in their first year who progress to their second year. Key limitations of these measures were that 1) there was no way to measure the reasons a student is not funded the following year (whether they did not apply or were not successful in an application), and 2) data collected on PSSSP students did not include information on year of study, so there was no means to gather metrics on progression from first to second year. For the first measure, the proportion of students successfully completing an academic year (but not yet graduating) who are funded the following year was approximately 70 percent. The figure is 25 percent for students who were not successful in a given academic year.

Without knowing how many of those students attempted to procure funding for PSSSP the following year, however, it is difficult to cast this as a measure of access or success. Additionally, policies of First Nation administrators themselves may not allow for funding in multiple years, or may prioritise first-year learners, for example. The key metric missing is demand relative to funding support.

Importantly, the ISC Departmental Plan for 2019-20 has revised the departmental desired outcome to "Indigenous students receive an inclusive and quality education," measured by the number of funded First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation students who graduate with a post-secondary degree/diploma/certificate (as of 2019-20, funding is available for Métis Nation post-secondary students for the first time). The approach to collecting this information had not yet been developed as of the writing of this report.

3.2 Success of Students Supported through UCEPP

Finding 2: Since 2010/11, more than half of students enrolled in UCEPP (annually) did not return to post-secondary institutions the following year, and one fifth progressed to an area of study.

The objective of UCEPP is to enable students to attain the academic level required for entrance into degree and diploma credit programs. According to data in the ERAS, the majority of students that were enrolled in UCEPP did not return the following year. Only a fifth progressed to a degree or diploma program.

| 2010-2011 to 2011-2012 |

2011-2012 to 2012-2013 |

2012-2013 to 2013-2014 |

2013-2014 to 2014-2015 |

2014-2015 to 2015-2016 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Remained in UCEPP between earlier and later year | ||||||||||

| Women | 170 | 22.5% | 130 | 19.8% | 147 | 16.4% | 257 | 29.1% | 266 | 25.9% |

| Men | 78 | 17.5% | 71 | 20.0% | 86 | 16.8% | 25 | 24.8% | 145 | 27.0% |

| Total | 248 | 20.6% | 201 | 19.9% | 233 | 16.5% | 382 | 27.5% | 411 | 26.3% |

| Progressed to another area of study between earlier and later year | ||||||||||

| Women | 174 | 23.0% | 161 | 24.5% | 239 | 26.6% | 212 | 24.0% | 239 | 23.3% |

| Men | 87 | 19.5% | 63 | 17.7% | 104 | 20.4% | 99 | 19.6% | 92 | 17.1% |

| Total | 261 | 21.7% | 224 | 22.2% | 343 | 24.3% | 311 | 22.4% | 331 | 21.2% |

| Did not return between earlier and later year | ||||||||||

| Women | 412 | 54.5% | 365 | 55.6% | 513 | 57.1% | 413 | 46.8% | 522 | 50.8% |

| Men | 281 | 63.0% | 221 | 62.3% | 321 | 62.8% | 281 | 55.6% | 300 | 55.9% |

| Total | 693 | 57.7% | 586 | 58.0% | 834 | 59.1% | 694 | 50.0% | 822 | 52.6% |

|

*A limitation of this table is that it only consider transitions between two consecutive years. It would not capture such situations as, for example, a student completing UCEP and taking a year off before enrolling into another program. Also, as part of the data cleaning exercise that was carried out prior to data analysis, multiple entries associated with the same student identifier in a given year were removed. Because the data in this table does not include duplicates, it does not capture a situation in which a student would transition from UCEP to another program within the same year. This is not considered to have an effect on the values presented in this table, as duplicate entries accounted for between 0.1% and 1.3% of entries in any given year. |

||||||||||

First Nation participants in site visits also echoed the notion that the demand is high for UCEPP funding, but the success rates were low, prompting many First Nation education administrators to deprioritize UCEPP applicants in favour of more PSSSP applicants. Although First Nations may not be prioritizing UCEPP, post-secondary institutions with upgrading programs recognize the need for such support and frequently target First Nations in their recruitment efforts.

UCEPP's low success rate calls into question whether the program is adequately targeting needsFootnote 9. Since it is funding students' access to existing entrance programs offered by post-secondary institutions, there are questions as to whether these programs, which are not normally tailored to the circumstances experienced by First Nation and Inuit learners, are meaningfully facilitating a transition.

A sentiment expressed by post-secondary institution administrators, and education administrators on reserve, is that where students may be on the cusp of achieving academic prerequisites, when coupled with the many reasons the students may need the extra support, the result is a tenuous hold on progress through the academic year.

In general, it was expressed by evaluation participants that Indigenous students do better when they see themselves in the academic institution they attend. Specifically, there is an expressed need for supports that are more tailored to their circumstances and needs. For students looking to upgrade, the need for support is often greater, and the financial support for the tuition for upgrading in and of itself is not sufficient in many cases to promote progression and attachment to academic programs.

A significant amount of the commentary on the challenges facing First Nation students in transitioning to post-secondary focused on the general academic unpreparedness of students, culture shock, fear of living away from home and the degree to which family issues at home could cause the student to end their academic semester early to return home. Students requiring upgrading were seen by participants as being more sensitive to these circumstances, and needing further support. Indigenous students and post-secondary institution staff interviewed suggested that this is further exacerbated by post-secondary teachers' and fellow students' low expectations of Indigenous students, often stemming from racism and lack of awareness. Academic literature refers to these low expectations as the expectation of primitiveness, the assumption that Indigenous students will be academically behind their peers.Footnote 10

Partnerships between First Nations and post-secondary institutions are key to better ensuring that First Nation students are supported beyond tuition for upgrading. Given the low success rate of students needing upgrading via UCEPP, there is clearly a need to invest more strategically beyond tuition for upgrading programs. More work with post-secondary institutions that may engage Indigenous partner organisations in developing programs designed to support the transition and retention of Indigenous students in post-secondary is needed.

3.3 Program Access

Finding 3: While the number of students supported by ISC post-secondary programs has increased, particularly for younger cohorts, ISC does not measure the degree to which these programs meet the actual demand among eligible prospective post-secondary students, and lacks a clear objective on the extent to which these programs are meant to facilitate access.

First Nation communities have autonomy to set priorities and make decisions about how eligible students receive funding for post-secondary education through PSSSP. Band councils or Inuit communities have variable approaches to prioritizing funding but often cannot fund all prospective students. According to case-study participants, those that do fund all eligible students make up the funding gap through other revenue sources, with federal post-secondary programs covering as little as 50 percent of total post-secondary supports in some cases.

This creates inequity amongst community members, and between communities. Some are able to fund all prospective students, while others can only fund a portion. Both Indigenous partners and post-secondary institutions indicated that funding per student is inadequate, and does not cover the costs associated with being a post-secondary student including housing, child care and school supplies.

While total funding for band council support and Inuit communities for post-secondary education can be examined, it is not informative, as there is no indication of amounts awarded to students, and no indication of how much of the awarded bursaries are from ISC versus other resources. Where this question was examined with First Nation education administrators, in all cases funds were procured from multiple sources, even to the point where it was not clear to administrators the extent to which PSSSP was providing support. An analysis of efficiency in this regard would require detailed analysis of band council financials, which would not be appropriate.

Thus PSSSP and UCEPP are better thought of as bursaries that are available based on how much revenue a band council and Inuit community can direct to post-secondary supports relative to the demand, rather than universally accessible for eligible individuals. Despite the fact that these are programs designed to enable access, ISC does not measure the extent to which this is achieved, as it does not measure demand or prospective uptake.

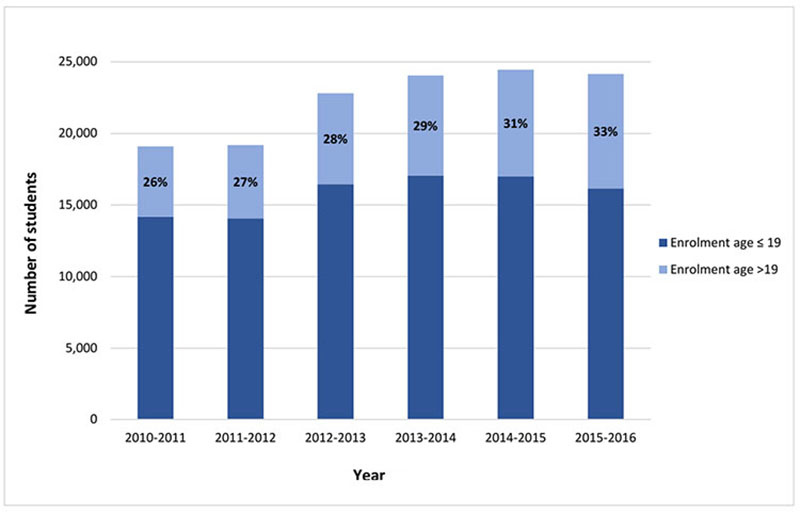

As shown in Figure 2, the number of students supported by ISC has increased by nearly 25 percent between 2010-11 and 2015-16. The increase seen in 2012-13 coincided with an increase in investments of about 8 percent, which has been relatively stable since.

Notably, the proportion of students 19 and younger has steadily increased over time, suggesting a growing number of students entering post-secondary straight out of, or soon after, completing high school (Figure 3). The proportion of these students who are enrolled in UCEPP has remained steady over time at between approximately 5 and 6.5 percent, increasing from about 1,200 students in 2010-11 to, 1,600 in 2015-16.

Figure 3. Number of students supported by ISC over time and by age category

Text alternative for Figure 3. Number of students supported by ISC over time and by age category

Figure 3 is a stacked bar chart illustrating the number of students supported by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), by year, and proportionally between students under the age of 19, and those over the age of 19.

During the period of 2010-2011, when 19,091 students were supported by ISC, 14,168 (74%) were under the age of 19, and 4,923 (26%) were over the age of 19.

During the period of 2011-2012, when 19,191 students were supported by ISC, 14,069 (73%) were under the age of 19, and 5,122 (27%) were over the age of 19.

During the period of 2012-2013, when 22,807 students were supported by ISC, 16,453 (72%) were under the age of 19, and 6,354 (28%) were over the age of 19.

During the period of 2013-2014, when 24,043 students were supported by ISC, 17,060 (71%) were under the age of 19, and 6,983 (29%) were over the age of 19.

During the period of 2014-2015, when 24,456 students were supported by ISC, 16,990 (69%) were under the age of 19, and 7,466 (31%) were over the age of 19.

During the period of 2015-2016, when 24,146 students were supported by ISC, 16,160 (67%) were under the age of 19, and 7,986 (33%) were over the age of 19.

Outside of these programs, there are no federal options for students unable to obtain adequate supports that are unique to First Nation or Inuit students. The delivery model for PSSSP and UCEPP was not identified by Indigenous partners as problematic per se, but the issue is an inability to fund all prospective students. If the department's goal is to enable access to post-secondary education for all prospective Indigenous post-secondary students, the current delivery model will not achieve that goal.

ISC's role as a funding agent is appropriate in the context of this program, but it lacks a clear policy position on the extent to which it is responsible for better promoting access to post-secondary for First Nation and Inuit students. While there would not be a desire among First Nation administrators to relinquish control of their funding directives for post-secondary education, there is room for the Government of Canada to give ISC or Education and Social Development Canada the mandate and funding to ensure that students who are unable to obtain adequate support from band-based funding for PSE have other options that are equitable to their peers receiving full financial supports. This could be in the form of a bursary for First Nation and Inuit students via the Canada Student Loans program, or other options within ISC.

3.4 Impacts of the Post-Secondary Partnerships Program (PSPP)

Finding 4: Academic institutions have contributed to making positive advances in relationships, partnerships and First Nation-driven academic programs, but this is still lacking in many institutions. There is a desire for PSPP to extend its reach to non-academic and support-based initiatives. The relative impact of the PSPP in this regard is unclear.

PSPP provides funding to develop Indigenous studies and courses in post-secondary institutions.

The main outputs attributable to the PSPP were the development of academic courses and programs. While ISC provides approximately $7 million per year in core funding to the First Nations University of Canada, additional proposal-based funds were disbursed to post-secondary institutions for courses and programs at several universities to support Indigenous learners: there were 87 selected projects with a total value of $15 million in 2014-15; 73 with a total value of $15 million in 2015-16; and a notable increase to 116 projects with a total value of $23 million in 2016-17.

Some of the centers offering support to Indigenous students beyond the development of academic programs do secure funding through the PSPP, but many noted that they experienced difficulties developing successful proposals, including not being provided with explanations for why their proposals are not accepted. This contrasts with the input from ISC regional offices, which indicated that they assist those submitting proposals and communicate back to those who have proposals rejected.

Further, although it is not the intent of the program to fund student support centres, many post-secondary institutions do have some form of Indigenous student support center that is responsible for recruiting prospective students and assisting Indigenous students throughout their post-secondary education. They assist prospective students with applications for academic programs, housing services, educational supports and access to other services on campus. As Indigenous students enter their studies, these offices offer them opportunities to connect with one another through culturally relevant events and activities. They act as a foundation for building a sense of community amongst Indigenous students.Footnote 11

Staff from these support centers shared a number of stories about the support they have provided to Indigenous students, and how their support was identified by students as a driving factor behind their success. Staff members go above and beyond to ensure the wellbeing of their students. Examples have included driving students to medical appointments and helping students try to come up with funds to travel home in the event of a family emergency. Literature suggests that these centers have difficulty providing all of the services they would like to, as a result of a lack of fiscal commitment from the institution they operate within and a lack of commitment to Indigenous support programs within the institution.Footnote 12 Interviews conducted with staff from Indigenous support centers echo these sentiments.

There were key examples of successful retention and progression being attributed to the support available at the post-secondary institution, including the availability of culturally-relevant resource centres, elders, and direct non-academic services. That said, many interviewees expressed that while there should be services targeted to Indigenous students, there is a need to integrate these with general student supports to promote cohesion and inclusion.

The main variable determining whether such support centres or services exist, according to interviewees, is the extent to which providing them is seen as a priority by the post-secondary faculties. Such services are well-established where post-secondary institutions prioritize recruitment and retention of Indigenous students, and thus there is variability from little to no tangible efforts towards Indigenous cultural awareness, to mandatory Indigenous studies courses at the University of Winnipeg and Indigenous law degrees such as that offered by the University of Victoria.

According to interviewees, there does not exist a strong federal support stream where universities can access funding for First Nation and Inuit student support beyond tuition grants and academic programs. Where student retention is difficult, it often stems from struggles with transition and adaptation to a new environment, coupled with poor public understanding of First Nation and Inuit histories and barriers. Incentivizing institutions to provide more supportive programs that assist with transition and support, particularly resources such as elders and facilities that can host culturally relevant activities and offer support, is expected to have significant impacts on wellbeing and retention.

Support for the development of academic Indigenous programs is essential to the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives and histories in post-secondary institutions. There is, however, a need to also incentivize post-secondary institutions to provide more non-academic support customized to Indigenous students. Interviews in this evaluation were clear that while support for Indigenous programs is positive, it needs to extend well beyond academic programs and into the core of the administrative support system in general.

3.5 Impacts of the Indspire Program

Finding 5: Indspire has been successful in providing scholarships, bursaries and recognizing and celebrating the achievements of Indigenous learners. Its value is seen in the promotion and celebration of success, and in promoting tangible career trajectories amongst engaged and high-achieving students.

The majority of Indigenous education administrators and Indigenous partners within post-secondary institutions indicated that Indspire is a highly recommended source of funding for prospective students. Students demonstrating a financial need can apply for funding through Indspire, and this is therefore an important resource for prospective students unable to obtain sufficient funding from PSSSP or other resources. Like most scholarship and bursary programs, Indspire requires applicants to demonstrate community engagement such as volunteerism, a targeted career plan and good academic performance. Therefore, the requirements to obtain funding are far more stringent than PSSSP, which normally requires a demonstration of membership to the student's band and need (although not always need). Therefore Indspire is not designed to act as a simple supplement for those unable to procure sufficient funds, as it is a scholarship uniquely for high-achieving students.

First Nation and post-secondary institution participants in this study lauded Indspire for being a source for the recognition of high-achievement recognition via awards and bursaries and scholarships. Two of the main caveats noted were that 1) the amounts of awards are not meant to cover actual costs, and thus successful students may still face significant shortfalls, and 2) priorities of band administrators in particular tend to centre on students who are not high achievers as they are more in need of supports. There was also commentary on the complexity of scholarship application processes, which may be unfamiliar to, or difficult for, students who have never had to demonstrate achievements and eligibility before, but may otherwise be eligible.

Some students expressed concerns about the degree of focus placed on oil and gas professions as being in conflict with some students' ethical considerations, and other issues of individual competition and recognition as being at odds with some traditions of humility, cooperation and modesty. Additionally, most Indspire materials are provided only in English and Francophone applicants generally cannot seek services in their first official language.

Importantly, however, Indspire has partnered with universities – for example, with McGill on its Indigenous bursaries and awards efforts to better promote the enrolment and retention of Indigenous students. Further, the success of Indspire is demonstrated by its expanding reach, with over 3,764 bursaries totaling $11.6 million in 2016-17, up significantly from 2,220 bursaries totalling $6.2 million in 2011-2012.This is also in addition to mentoring, peer support and conferences, as well as the annual awards ceremonies celebrating high achievements.

According to Indspire, 96 per cent of Indigenous students who receive funding graduate with post-secondary degrees or diplomas, and 53 per cent go on to pursue post-graduate degrees.

3.6 Adult Learners Completing Secondary

Finding 6: ISC lacks a policy on adult learners looking to complete secondary, which has adverse effects on their ability to pursue post-secondary and/or enter the labour market.

ISC lacks a policy focus on adults over 21 looking to complete secondary, and consequently, support is highly variable between communities. Where students over the age of 21 are supported to complete high school or equivalencies, it is done via work-arounds of ISC policy, and is most often paid for by provincial government programs, First Nations' own resources where they are available or the student's own financing options.

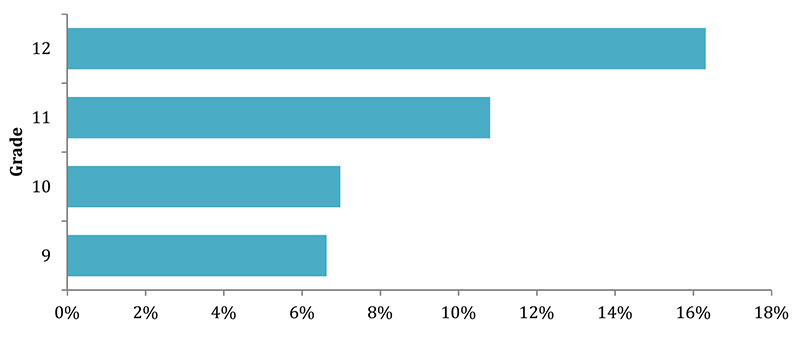

While there are students included in the Nominal RollFootnote 13 over 21, the number of students over 21 pursuing the completion of secondary studies is greatly understated by this database, as they are not included as a matter of policy. That being said, between 2010-11 and 2015-16, typically 16 percent of grade 12 students on the Nominal Roll were over 21. Nearly 7 percent of students enrolled in grade 9 and 10, and 11 percent of students enrolled in grade 11, are 3 or more years older than their grade cohort norms (and thus on track to be over 21 if they reach grade 12, see Figure 4).

Importantly, the average age of enrolment for grade 12 was 20.3 years old between 2010-11 and 2015-16. Critically, these figures do not include students over 21 who pursue completion of secondary studies through other means than the First Nation education system. The figures also do not include cases where students pursue a grade 12 equivalency, and they cannot reveal situations where the First Nation provides support for the students outside the policy scope by using resources other than PSSSP – in these cases the students may attend school but may not be recorded on the Nominal Roll.

Figure 4: Proportion of secondary students 3 or more years older than the cohort norm

Text alternative for Figure 4: Proportion of secondary students 3 or more years older than the cohort norm

Figure 4 is a bar chart illustrating the percentage of students by grade who are 3 or more years older than the age norm for that grade cohort on the Nominal Roll. The Nominal Roll refers to the registry of students funded under the elementary and secondary education program via Indigenous Services Canada.

6.6% of students in grade 9 were 3 or more years older than the cohort norm.

6.9% of students in grade 10 were 3 or more years older than the cohort norm.

10.8% of students in grade 11 were 3 or more years older than the cohort norm.

16.3% of students in grade 12 were 3 or more years older than the cohort norm.

Participants were asked whether the maximum age of enrolment for secondary studies should be raised (or whether there should be an age limit) as a matter of policy, and it was generally felt that older students would not wish to pursue secondary studies with a much younger cohort, and that they should instead be supported as adult learners with unique needs under post-secondary program options, or under a separate program entirely.

But where a First Nation wishes to offer adult education under its post-secondary programming, completion of secondary studies is not covered under the PSSSP or UCEPP, and, if it was, support would be limited by the resources and priorities of individual communities, and not as a matter of entitlement in the same way as access to secondary education for students 21 and under. The completion of secondary studies as a pseudo-post-secondary program would also require access to institutions outside the First Nation or beyond classic provincial secondary schools system, and would be more akin to a cross between UCEPP and PSSSP support.

It is difficult to estimate the extent to which this policy gap results in older students not completing secondary school. Given the average age of grade 12 enrollees, however, and the high frequency of grade 12 students aged 21 and older in the Nominal Roll despite their exclusion in policy, it is safe to assume the number is significant.

The First Nations Regional Early Childhood, Education, and Employment Survey found that while 28 percent of those who did not complete high school are employed, nearly half (49.2 percent) of those who completed high school and nearly two thirds (61.2 percent) of those who completed post-secondary education are employed.

First Nation participants in the 2017 evaluation of Income Assistance On-Reserve observed that many young adults apply for Income Assistance as a default when they turn 18. This in turn normalizes Income Assistance reliance, where the option of not applying for Income Assistance would put a youth at a clear disadvantage compared to their peers. Critically, the Income Assistance dependency rate, while showing gradual declines in recent years, was still over 20 percent for 18-24 year olds on reserve in 2017. First Nation participants in this evaluation indicated that, where students have not completed, or are not supported in completing, their secondary studies as adults, they will almost invariably apply for Income Assistance. In the context of the total budget for Income Assistance On-Reserve having increased from $823 million in 2010-11 to $924 million in 2016-17, and budgets after 2018 surpassing $1 billion annually, as stated in that evaluation, education of the young adult population is key to addressing this issue.

While departmental data on Income Assistance does not lend itself to estimating the relative share of expenditures attributable to the 18-24 population, or the relative share of those not having completed secondary studies, it is probable that the costs associated with providing wide or even universal access for adult learners to complete secondary studies on reserve would decrease Income Assistance reliance and significantly boost enrolment in post-secondary and/or participation in the labour force.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

While ISC programs are supporting post-secondary learners in accessing tuition and others supports, and supporting the Indigenous programs in institutions and recognition of Indigenous achievements, an ambitious strategy is needed to address gaps in post-secondary education and labour-market inclusion. Most critically, as PSSSP is a post-secondary access program, demand needs to be measured, and ISC should strategize how to meet this demand. This, combined with fully supporting adult learners in completing their secondary studies, is expected to significantly open up opportunities for more Indigenous individuals to post-secondary, and the labour market, where they are significantly underrepresented.

Additionally, significant support is needed to better position post-secondary institutions and other organisations in their work on the successful transition and retention of Indigenous learners. Efforts are needed to expand the reach of the PSPP beyond academic programs and into the social and institutional environment of post-secondary institutions in general.

Therefore, it is recommended that ISC:

- Work with First Nation and Inuit partners, and consult with Employment and Social Development Canada and other departments or ministries and academic institutions, to develop a strategy to provide more equitable access to post-secondary funding supports for all prospective First Nation and Inuit students;

- Work with First Nation partners to develop a clear policy for adult learners to complete secondary studies and boost eligibility for post-secondary and labour-market entry;

- Work with First Nation and Inuit partners to develop a strategy to support students who wish to pursue post-secondary studies – whether they are transitioning into post-secondary and need to complete secondary or upgrade, or whether they are attending post-secondary and need support to stay in school – beyond tuition through enhanced, culturally appropriate wrap-around supports;

- Work with First Nation and Inuit partners to develop a measurement strategy to assess demand for post-secondary funding supports, the needs of eligible learners, and the impact of federal funding in addressing the needs of eligible learners (i.e. differentiated from other funding sources at the band level); and,

- Broaden the PSPP to include more non-academic and transitional supports, and improve communications with prospective funding recipients to ensure clarity and transparency in funding decisions.