Evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program

July 2019

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

PDF Version (328 Kb, 36 Pages)

Table of contents

Acronyms

| CIRNAC |

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada |

|---|---|

| FNIHB |

First Nations and Inuit Health Branch |

| FNIHCC |

First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program |

| ISC |

Indigenous Services Canada |

| NIHB |

Non-insured Health Benefits |

Executive Summary

The First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program (FNIHCC) has demonstrated considerable success over the past five years, with continued improvements largely due to effective program management and dedication of First Nation health directors and/or Home and Community Care coordinators and nurses.

In light of the growing and aging population, and more continuous improvements in the ability to appropriately diagnose clients and assess needs (which is expected to result in increased demand), the needs of clients are quickly expanding and becoming more complex. Additionally, First Nations and Inuit communities face greater complexities and barriers to effectively meeting client needs when compared to other communities. This is particularly true considering the poorer health outcomes of the First Nation and Inuit populations, availability of resources and facilities, and the need to deliver programs in a culturally appropriate manner.

Despite the growing and aging population, and perceptions among service providers of a growing demand, program data show small decreases in the total number of clients and the number of service hours per client. A key issue is that demand is not systematically measured – only the service provided. Therefore, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) is not currently able to measure the extent to which it meets demand, and unable to anticipate future growth with accuracy.

In general, most health care workers in the First Nation and Inuit communities surveyed felt that their services were superior, their wait times shorter, and that the needs of their clients were better met in their communities than they would be in other neighbouring non-Indigenous communities. According to interviewees in this evaluation, the increased investments in training, planning and work towards accreditation have helped.

Given the continued rapid population growth and growing complexities of client needs, there is a considerable risk that recent gains may be negatively impacted if the current approach to funding is not revisited.

This evaluation specifically makes the following observations:

- Demand for services is projected to increase and become more complex.

- The priorities of the Government and Indigenous communities are generally aligned with respect to the care provided under FNIHCC; however, existing policy and legislative gaps risk creating or maintaining disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

- Communities are supported in their training and capacity-building efforts, but there are gaps especially for personal care providers, and these disproportionately affect smaller and more remote communities.

- In general, evaluation participants believed First Nation and Inuit people have access to services that in many cases is seen as superior to neighbouring non-Indigenous communities.

- The extent to which clients are provided with quality services and are having their needs met is viewed generally positively, but limited resources and communication issues were cited as barriers to meeting client needs.

- FNIHCC coordinates and collaborates with other programs and services at both local and regional levels. In some communities, FNIHCC and the Assisted Living programs have been integrated from a service delivery perspective.

It is therefore recommended that ISC:

- Develop a strategy to measure current and prospective demand of services relative to capacity to provide services, in order to better inform policy directions on the extent of need as well as the coverage of different types of services.

- Better support communities in the training of personal care providers and to address issues of recruitment and retention of qualified FNIHCC personnel.

- Work with communities to develop communications strategies to improve coordination and communication with provincial/territorial/regional health services.

- Where desired by communities, provide more flexible funding options that cover the spectrum of services currently available through both the FNIHCC and Assisted Living Program, including working with communities who wish to move from set to flexible funding arrangements to better manage services in the long term.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program

Project #: 1570-7/16131

1. Management Response

This Management Response and Action Plan has been developed to address recommendations resulting from the Evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program (FNIHCC), which was finalized by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement, and Review Branch.

The First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) recognizes the findings highlighted by the evaluation regarding the relevance and performance of the program. Specifically:

- The demand for services is projected to increase and become more complex.

- The priorities of the Government and Indigenous communities are generally aligned with respect to the care provided under the program; however, existing policy and legislative gaps risk creating or maintaining disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

- Communities are supported in their training and capacity-building efforts, but there are gaps especially for personal care providers, and these disproportionately affect smaller and more remote communities.

- In general, evaluation participants believed First Nations and Inuit have access to services that in many cases is seen as superior to neighbouring non-Indigenous communities.

- The extent to which clients are provided with quality services and are having their needs met is viewed generally positively, but limited resources and communication issues were cited as barriers to meeting client need.

- The program coordinates and collaborates with other programs and services at both local and regional levels. In some communities, the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program, and the Assisted Living Program have been integrated from a service delivery perspective.

The evaluation provides four recommendations to improve the design and delivery of the program. All recommendations are accepted by the program and the attached Action Plan identifies specific activities to move towards meeting these recommendations.

The Department will proceed with implementing a three-year staged response to co-develop and implement operational and policy improvements to the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program. An annual review of this Management Response and Action Plan will be conducted by the Departmental Evaluation Committee to monitor progress and activities.

The staged approach recognizes program complexities and provides time to engage First Nations and Inuit partners and others in a meaningful co-development process. This approach will also help ensure that any actions taken complement broader Government of Canada initiatives (e.g. New Fiscal Relationship, reduction in reporting burdens), initial thinking with the Assisted Living Program on the development of a continuing care strategy, the Government of Canada response to the Report of the Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs entitled "The Challenges of Delivering Continuing Care in First Nation Communities", or changes to complementary initiatives and programs (e.g. Jordan's Principle, the Assisted Living Program, Child and Family Services, and infrastructure and housing programs).

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Develop a strategy to measure current and prospective demand of services relative to capacity to provide services, in order to better inform policy directions on the extent of need as well as the coverage of different types of services. | We do concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister FNIHB | Start Date: April 2019 |

We agree with this recommendation. FNIHB has made significant investments in the Home and Community Care Program, including additional funding to expand service hours and increase palliative care services. In addition, over a three-year period, we intend to co-develop and implement a measurement strategy that will provide data on the current demand for services as well as allow for trend analysis that could be used with other data sources to support prediction of future demands. We intend to develop a regional engagement process in 2019-2020 and will subsequently revise our strategy as required to reflect the appropriate next steps based on our work with First Nations, Inuit and other partners.

|

Executive Director of Primary Care and Chief Nursing Officer, Regional Executives Heads | Completion: April 2021 |

|

| 2. Better support communities in the training of personal care providers and to address issues of recruitment and retention of qualified FNIHCC personnel. | We do concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister FNIHB | Start Date: April 2019 |

We agree that there is a need to support communities in the training of community employed personal care providers and helping communities address their recruitment and retention issues. We intend to build upon opportunities available for funding through the Aboriginal Health Human Resource Strategy recognizing the limitations of this funding. The Department also recognizes that issues related to recruitment and retention of health care workers is widespread across Canada in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, and as such is an ongoing issue.

|

Executive Director of Primary Care and Chief Nursing Officer, Regional Executives Heads | Completion: March 2020 |

|

| 3. Work with communities to develop communications strategies to improve coordination and communication with provincial/territorial/regional health services. | We do concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister FNIHB | Start Date: April 2019 |

We agree that program staff should work with communities to improve coordination and communication with provincial / territorial / regional health services. The department recognizes that improvements in communication and coordination of services requires ongoing dialogue and is committed to supporting communities as they develop relationships with regional health authorities and with provincial / territorial health services.

|

Executive Director of Primary Care and Chief Nursing Officer, Regional Executives Heads | Completion: March 2021 |

|

| 4. Where desired by communities, provide more flexible funding options that cover the spectrum of services currently available through both the FNIHCC and Assisted Living Program, including working with communities who wish to move from set to flexible funding arrangements to better manage services in the long term. | We do concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister FNIHB | Start Date: April 2019 |

We agree that where desired, and where community General Assessments support, communities should be supported to move from set agreements to flexible funding arrangements, and block agreements. We also agree that additional flexibility can be gained through improving the alignment between the FNIHCC and the Assisted Living Program so as to provide a more comprehensive spectrum of services.

|

Executive Director of Primary Care and Chief Nursing Officer, Regional Executives Heads |

Completion: March 2020 |

1. Introduction

After the creation of the new departments of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) in November 2017, the programs of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch moved from Health Canada to ISC. At that time, an evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program (FNIHCC) was underway, and governance of the evaluation moved to ISC's Audit and Evaluation Sector, with continued involvement of the evaluation team at Health Canada.

The evaluation covered the period from 2012 to 2017. Research included a review of administrative data and literature, 55 interviews and a web-based survey of 131 health directors and/or Home and Community Care coordinators and nurses. The evaluation questions, as well as methodological notes and limitations, are outlined in Appendix A. The evaluation was conducted at the same time as the evaluation of ISC's Assisted Living Program.Footnote 1 Notes on the intersection between these programs are noted throughout this report, and there are recommendations that implicate both.

The scope of the evaluation included all program activities funded under the FNIHCC Program at the national and regional levels. It covered all delivery contexts, including for First Nations, where program funds are provided via contribution agreements, and Inuit communities, where the program is managed by territorial governments. Out of scope were activities taking place in British Columbia, where all responsibilities for federal health programs have been transferred to the First Nations Health Authority through the British Columbia Tripartite Framework Agreement on First Nation Health Governance.

2. Background

Program Description

FNIHCC administers contribution agreements with First Nation and Inuit communities and territorial governments to fund the administration of home care by registered nurses and trained certified personal care workers in 455 First Nation and Inuit communities. This is to enable First Nations and Inuit individuals with disabilities, chronic or acute illnesses, and the elderly to receive the care they need in their homes and communities. Care is delivered primarily by home care registered nurses and trained certified personal care workers.

FNIHCC supports the delivery of a continuum of basic home care services. This suite of services is based on a case management approach that includes client assessment and reassessment, which can involve the client, family caregivers or service providers, and help determine a client's needs and the services required. Home care nursing includes direct service delivery, personal care services and support to family caregivers. The basic home care services also encompass home support (e.g., bathing and grooming, home management assistance, etc.), as well as in-home respite benefiting clients, families and caregivers. The program also entails access to medical equipment and supplies, management and supervision, data collection and record-keeping, as well as linkages and referral, as needed, to other health and social services. Depending on community needs, priorities, infrastructures and resources, the Program may also incorporate supportive services: rehabilitation and other therapies; adult day programs; meal programs; in home mental health; in home palliative care; and, specialized health promotion, wellness, and fitness services.

The program is guided by delivery principles, which emphasize respect for both traditional and contemporary approaches to healing and wellness; respect of community priorities; availability for those with assessed need; delivery of evidence-informed, integrated quality care; support for individuals, families and communities; and the pursuit of sustainable funding to provide continuous care.

Objectives and Outcomes

The specific objectives for FNIHCC are to:

- build the capacity within First Nations and Inuit communities to develop and deliver comprehensive, culturally sensitive, accessible and effective home care services at a pace acceptable to the community;

- assist First Nations and Inuit living with chronic and acute illness in maintaining optimum health, well-being and independence in their homes and communities;

- facilitate the effective use of home care resources through a structured, culturally defined and sensitive assessment process to determine service needs of clients and the development of a care plan;

- ensure that all clients with an assessed need for home care services have access to a comprehensive continuum of services within the community, where possible;

- assist clients and their families to participate in the development and implementation of the client's care plan to the fullest extent and to utilize available community support services where available and appropriate in the care of clients; and

- build the capacity in First Nations and Inuit to deliver home care services through training and evolving technology and information systems for monitoring care and services, and to develop measurable objectives and indicators.

The intended outcomes of FNIHCC are:

- improved access to home and community care services;

- increased effectiveness of services;

- improved coordinated and seamless responses to home and community care needs; and

- increased use of quality improvement, including patient safety processes, to respond to home and community needs.

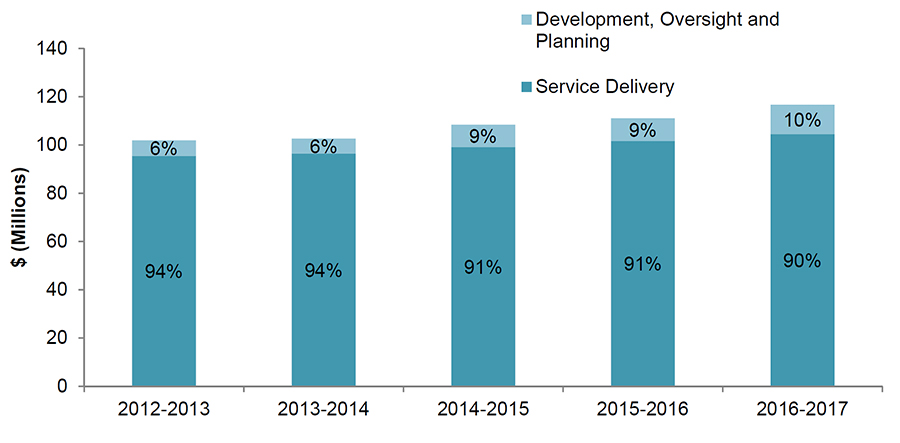

Program Funding

Total expenditures under the Home and Community Care Program over the evaluation period were approximately $541 million. Program expenditures have increased by 15 percent since 2012-13 from $101.9 million to $116.7 by 2016-17. In 2016-17, service delivery represented 90 percent of annual expenditures for the program, followed by policy development and oversight that represented seven percent of expenditures and professional development representing three percent of annual expenditures. Most expenses are categorized as contributions, representing 93 percent of expenditures in 2016-17.

| Activity Area | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Development and Program Oversight | 4.3 | 4.1 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 8.6 | 29.1 |

| Service Delivery | 95.5 | 96.4 | 99.1 | 101.6 | 104.5 | 497.1 |

| Professional Development | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 12.9 |

| Planning | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| TOTAL | 101.9 | 102.6 | 108.4 | 111.1 | 116.7 | 540.7 |

Source: Office of the Chief Financial Officer, Health Canada |

||||||

3. Key Findings

3.1 Continued Need

Finding 1. Demand for services is projected to increase and become more complex.

Among the Canadian population in general, personal care needs are becoming more complex, due in part to earlier release from hospitals, long-term care facilities focusing primarily on very high care need clients, comorbidityFootnote 2 of chronic disease, and increased desire to receive care in the home or community setting. Survey respondents for this evaluation corroborated this reality, reporting that demand for all FNIHCC services has increased significantly. This stands in contrast to data from FNIHB showing a decrease in actual funded hours and clients. However, demand is not measured by this data - only approved service delivery. The data therefore do not allow an analysis of level of service given relative to demand.

A perceived growing demand is occurring across Canada, but should be expected to disproportionately affect First Nations and Inuit. For example, compared to the non-Indigenous population, the prevalence of diabetes (20.7 percent compared to 6.2 percent), tuberculosis (25 times higher for First Nations, 154 times higher for Inuit), and other chronic conditions and communicable disease is far higher among First Nation and Inuit populations.Footnote 3

Most respondents to the web-based survey referenced in Section 1 indicated that the demand for services across multiple activity types has increased, despite the decrease in the total number of service hours per client (see Section 3.4 for further discussion), including:

- Managing and coordinating care

- Home care nursing services

- In-home health care support services or in-home personal care

- Linking with other professionals and social services

- Access to specialized equipment, supplies and pharmaceuticals

- In-home services such as homemaking, house cleaning, meal preparation or companion/attendant support

- Client assessments

- Record keeping and data collection

- In-home respite care

- Need for admittance to long-term care facility

- Palliative care services

Notably, service providers who deliver/oversee both FNIHCC and Assisted Living services were more likely to report that demands for managing and coordinating care have increased (96 percent), compared to those who deliver/oversee FNIHCC services only (75 percent).

Additional pressures that impact First Nation and Inuit communities are the limited availability of local facilities, cultural considerations in caregiving, and increases in youth with care needs stemming from Jordan's Principle (specifically, the clearer accountabilities and requirements to respond/act in a timely manner in these cases adds strain to an already strained system).Footnote 4 The increase in demand is more pronounced where communities are more geographically isolated.

The rate of overall utilisation among the population is seven percent among all Canadians over 15, and this is similar in First Nations and Inuit communities. Additionally, the fact that seniors are the highest users of services, coupled with the growing population of seniors, will create increasing pressures. However, the segment of the First Nations population aged 45 years and older is expected to more than double by 2026 from approximately 63,000 in 2001 (21 percent of the population) to 159,000 in 2026 (31 percent of the population). The growth estimate of the older cohorts for Inuit is an expected growth rate of 4.9 percent, increasing from 17 to 22 percent over the same period.Footnote 5 This trend is similar among the general population in Canada with estimates of seniors representing between 23 percent and 25 percent of the population by 2036, compared to 14 percent in 2009.Footnote 6

As a result, hospitals and long-term care facilities will continue to face increasing pressures to serve clients and patients with greater need, which may inadvertently result in lower prioritisation of those with less urgent needs, while also shortening hospital stays, and shifting the pressure to at-home care. While this shift may often be appropriate and even desired by clients and patients, it is important that administrators are able to accommodate increasing demands going forward. It is therefore essential to measure the current and prospective demand to be placed on administrators to accommodate needs, as current data do not capture what is needed; only what is provided.

With an expanding need to serve clients in their homes comes a growing need to ensure communities are able to deliver services and accommodate client needs in a culturally-consistent manner. Findings from the literature indicate that there is a continuing need for First Nations and Inuit communities to be able to define and receive health services. This goes beyond the need for cultural sensitivity and cultural competency (which are also critically important). Rather, it speaks to directly addressing the power relations between service users and service providers (addressing some Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Report).Footnote 7 Specifically, it indicates a need for increased funding of Indigenous health centres, recognizing the value of Indigenous healing practices and their use in the treatment of Indigenous patients in collaboration with Indigenous healers and Elders, to increase the number of Indigenous professionals working in health care, and to provide cultural competency training for all health care professionals.

3.2 Alignment Between the Priorities of Government and Indigenous Communities

Finding 2. The priorities of the Government and Indigenous communities are generally aligned with respect to the care provided under FNIHCC; however, existing policy and legislative gaps risk creating or maintaining disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

First Nations and Inuit service administrators that participated in this evaluation viewed FNIHCC as aligned with their priorities, and as being culturally appropriate (e.g. Indigenous control over how client services operate). Representatives of Indigenous organizations at the national and regional levels participating in key informant interviews noted relatively high levels of perceived "ownership" of the program by communities. This sense of ownership has contributed to the perception of FNIHCC as being delivered in a culturally-consistent manner, as communities are responsible for hiring and training staff, and making them aware of cultural practices.

The vast majority of survey respondents (90 percent) indicated that services were delivered in a highly or somewhat culturally-responsive and appropriate manner. Notably, however, more non-Indigenous (57 percent) than Indigenous (46 percent) respondents agreed that services were highly culturally-responsive and appropriate.

The Government of Canada has agreed to implement the Truth and Reconciliation Report recommendations, including Call to Action [19], stated below:

- We call upon the federal government, in consultation with Aboriginal peoples, to establish measurable goals to identify and close the gaps in health outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities…"

However, most health care to First Nations and Inuit is provided and funded by the provincial/territorial systems, and is provided in off-reserve hospitals and clinics. The health services funded by the federal government are provided primarily on-reserve and are in the areas of health promotion, health education services, with some public health and environmental health services. The federal government also funds primary health care in remote and isolated First Nation communities, home and community care and health promotion and disease prevention programs to First Nations and Inuit in the territories.

There is no specific statutory authority for the provision of health care programs and services to First Nations and Inuit by the Government of Canada. The Constitution Act of 1867 does not explicitly include "health" as a legislative power assigned either to Parliament (in Section 91) nor to the provincial legislatures (in Section 92). Nonetheless, the Courts have confirmed that most aspects of the regulation of health care are within provincial jurisdiction. For example, provinces have extensive authority over public health as a local or private matter under s. 92(16) of the Constitution Act, 1867; over the regulation of medical professions as matters of property and civil rights under s. 92(13); and over hospitals under s. 92(7).

The specific health care programs and services provided or funded by FNIHB are approved annually by means of the Appropriations Act, which grants Parliamentary approval to the Minister for the budgets and objectives of FNIHB. Treasury Board provides authority for specific program activities. However, in the absence of any clear statutory authority, which describes and defines the mandate of the programs and services, FNIHB provides or funds health programs and services to First Nations and Inuit based on Health Canada's departmental mission and mandate statements and on policy in a manner intended to be consistent with the 1979 Indian Health Policy and as such, are subject to the discretion of the Government.

The shift of these health programs from Health Canada to ISC further complicates any clarity in jurisdictional responsibilities, which has been the subject of some reports of the Office of the Auditor General. There is a lack of ongoing coordination among federal and provincial jurisdictions, which has led to a lack of clarity regarding what services are to be provided, at what service levels, and what legislation applies. All levels of government have acknowledged that gaps created by jurisdictional conflicts contribute to the health disparities among Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

The establishment of long-term care facilities in communities was stated as a main priority by all participants, but currently the resources needed to achieve this priority are greater than the funding available.

3.3 Training and Capacity

Finding 3. Communities are supported in their training and capacity-building efforts, but there are gaps especially for personal care providers, and these disproportionately affect smaller and more remote communities.

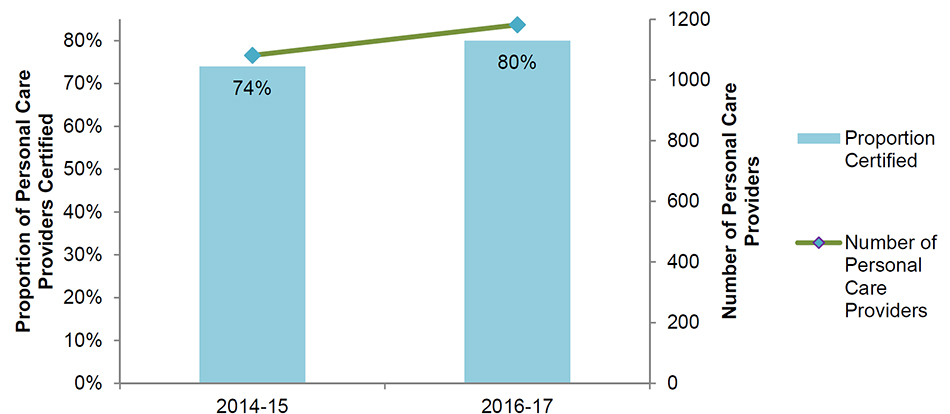

The ratio of FNIHCC nurses to population remained relatively constant over recent years at about 1.2 to 1.3 full-time equivalent nurses per 1,000 people. All nursing services are provided by regulated and licensed staff. As of 2016-17, approximately four out of five personal care providers were certified. The number of personal care providers, as well as the proportion of those certified, continues to increase, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Increase in both the total number of personal care providers and the proportion that are certified

Description of Figure 1: Increase in both the total number of personal care providers and the proportion that are certified

Figure uses a column graph to show an increase in the proportion of personal care providers certified has increased from 74 to 80 percent from 2014 -15 to 2016-17, and a superimposed line to show an increase in the total number of personal care providers from approximately 1,080 to 1,180 over that time frame.

Dedicated funding envelopes for training are provided and prioritized (e.g. continuing education) at a regional level by the health directors, nurse managers and FNIHCC coordinators. Much of the training focuses on nurses, but much less so for personal care providers, who do not have a specific funding allocation for training.

According to ISC's 2018-19 Departmental Plan, the Department intended to strengthen the support of health practitioners working in isolated contexts and also to improve the quality of care in these settings, and the Department is continuing its efforts in mandatory training, professional development, recruitment and retention, cultural safety, and accreditation.

Some of the specific activities targeted to small and remote communities highlighted in this evaluation included:

- Increasing access to nurse practitioners and interdisciplinary team models;

- Improving access to pharmacy services;

- Expanding access to physician supports in an on-call setting and first responders in communities;

- Strengthen regional capacities in nursing recruitment and retention; and

- Enhancing community capacity to deliver culturally appropriate palliative care services in the home setting.

These priorities stem from increased investments from Budget 2017 of an additional $184.6 million over five years.

A priority for training over the period covered by the evaluation has been on cultural safety and sensitivity, including topics such as intergenerational trauma, mental health, and health concepts from an Indigenous perspective.

3.4 Sufficiency of Amount of Services Provided

Finding 4. In general, interview and survey respondents believed First Nation and Inuit people receive an amount of service hours that in many cases is seen as superior to neighbouring non-Indigenous communities, but significant gaps remain.

As shown in Table 1, funding overall has increased modestly; notably, the proportion devoted to policy development and oversight, and professional development has nearly doubled – see Figure 2.

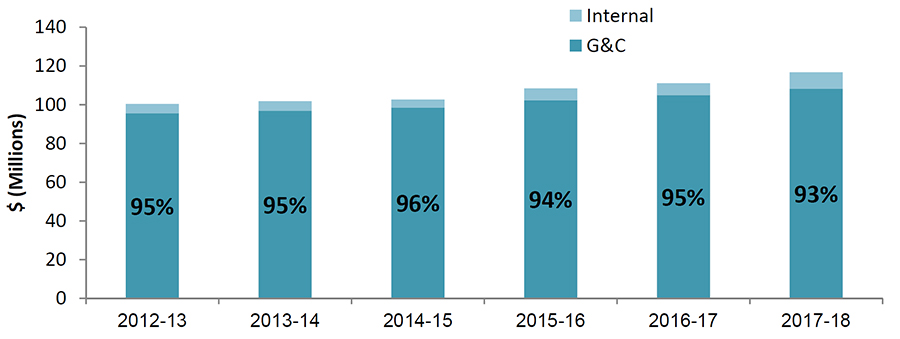

When examining the proportion of expenditures devoted to Grants and Contributions, whether for the direct provision of services, or development, oversight and planning, the total amount has increased from $95.5 million to $108.1 million between 2012-13 and 2017-18. The proportion of expenditures spent internally on salary and operations and maintenance has increased from approximately $4.8 million to $8.6 million over this period.

Internal expenditures as a proportion of the total have increased very slightly from five to seven percent (Figure 3). Notably, however, this trend is not seen in regional data (see Appendix B), where the internal expenditures portion of regional funds is consistently around three percent. The increase in internal expenditures has largely been at Headquarters.

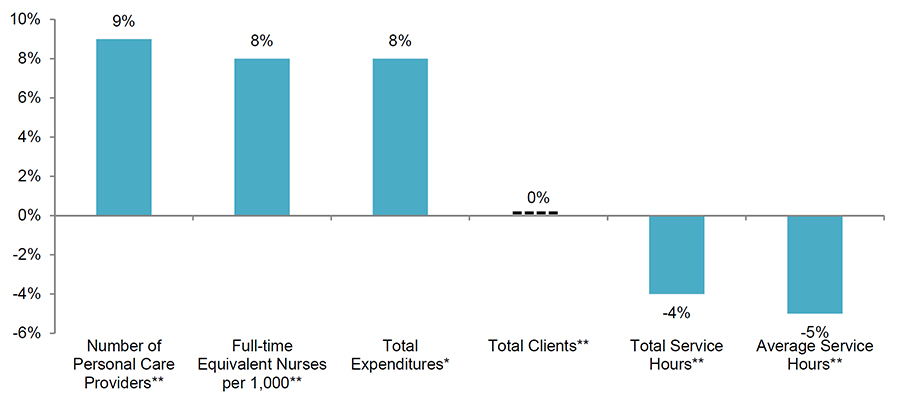

Over the past three years, funding for, and numbers of, FNIHCC delivery staff increased, while the number of service hours decreased. The total clients served per year remained the same between 2012 and 2017. This may be explained by the increasing demand being placed on FNIHCC staff to undertake coordinating and management of care roles, which leaves less time for direct service. A reduction in hours could also be partially due to new techniques and therapies or realising efficiencies. An increased cost of services may also result in service reductions where budgets become prohibitive. Figure 4 shows the percentage changes in this figure from 2012 to 2017.

Figure 2: Total spending has increased modestly from 2012-13 to 2016-17, most notably in development, oversight and planning

Description of Figure 2: Total spending has increased modestly from 2012-13 to 2016-17, most notably in development, oversight and planning

Figure uses a stacked column graph to show the total expenditures increasing from close to 100 million dollars in 2012-13 to close to 110 million in 2016-17, with the proportion of these expenditures represented by service delivery decreasing gradually from 94 to 90 percent, and the proportion represented by development, oversight and planning increasing gradually from 6 to 10 percent over this timeframe.

Figure 3: Internal expenditures as a proportion of total expenditures have increased modestly over time

G&C: Grants and Contributions

Description of Figure 3: Internal expenditures as a proportion of total expenditures have increased modestly over time

Figure uses a stacked column graph to show total expenditures increasing from close to 100 million dollars in 2012-13 to close to 110 million in 2016-17, with the proportion of these expenditures represented by internal expenditures increasing slightly from 5 to 7 percent, and the proportion represented by grants and contributions decreasing slightly from 95 to 93 percent over this timeframe.

Figure 4: Care providers, nurses and total expenditures have increased with a simultaneous decrease in total and average service hours between 2012 and 2017

Source: Administrative Data provided by FNIHB

* Includes all expenditures

**Excludes northern region

Description of Figure 4: Care providers, nurses and total expenditures have increased with a simultaneous decrease in total and average service hours between 2012 and 2017

Figure uses a column graph to compare changes, with a 9 percent increase in the number of personal care providers, an 8 percent increase in the number of full-time equivalent nurses per 1000 people, an 8 percent increase in total expenditures, a 0 percent change in the total number of clients a 4 percent decrease in the total service hours, and a 5 percent decrease in the average number of service hours.

In terms of general access, it was felt by the great majority of health directors and FNIHCC staff interviewed and surveyed that the amount of services was the same as or greater than neighbouring non-Indigenous communities for home care nursing, in-home health care support or in-home personal care services, and especially for in-home services such as homemaking, house cleaning, meal preparation or companion/attendant support.

It is worth noting, however, that most of the respondents to this survey were those tasked with administering the provision of these services, and there is no adequate data to support or refute this view. In essence, a measure of provincial or other community comparability says nothing of adequacy itself, because neighbouring communities may not be adequately providing access. If the goal is 'adequate' access, it would be necessary to better assess the level of need relative to what is provided, regardless of how that compares to non-Indigenous communities.

Key issues raised by intereviewees about access to services included:

- Variability between provinces, where multi-jurisdictional issues can complicate access and make it difficult for clients to navigate the various services and supports;

- In some regions, poor communication with the province results in challenges regarding discharge plans from a provincial care institution;

- Access to the program is generally available, but the resources available and services and supports provided are not necessarily meeting the needs of clients;

- Lack of 24/7 supports and services;

- Lack of access to specialists, particularly in smaller and more remote communities, for rehabilitation, occupational therapy, etc.; and

- Lack of economies of scaleFootnote 8 in smaller communities with higher costs.

Interviewees indicated that where there are funding shortfalls, it results in various gaps, such as coverage for children (however, this is largely recently being addressed by programs affiliated with Jordan's Principle), mental health, opioid addiction, medications, wound care, foot care, diabetic care, and may result in caregiver fatigue. Smaller and remote communities may face additional challenges accessing training; for example, connectivity issues restricting online training, challenges in bringing trainers into communities, and difficulty backfilling a position if an employee leaves the community to attend training.

3.5 Meeting Needs and Quality of Services

Finding 5. The extent to which clients are provided with quality services and are having their needs met is viewed generally positively, but limited resources and communication issues were cited as barriers to meeting client needs.

Overall, in the survey, respondents reported higher quality of services, and lower wait times, than similar programs in non-Indigenous communities. The quality of services was primarily attributed to the quality and dedication of service delivery personnel, and it was felt that quality was further supported when services are accredited.Footnote 9 Administrative data derived from the Community-Based Reporting Template that indicated approximately 25 percent of communities in 2015-16 had an accredited Home and Community Care program.

Representatives from Indigenous organizations noted that the smaller and more remote communities can be at a disadvantage regarding quality of services offered in part due to the challenges encountered in recruiting and retaining the required staff able to deliver quality services. Some indications of the quality of services highlighted by interviewees included perceived low rates of readmission to a hospital within 30 days of discharge and low rates of clients requiring hospitalization services since their last FNIHCC assessment, although there is no data to support or refute these perceptions.

Service providers and health directors are typically familiar with the Quality Resource Kit;Footnote 10 however, only about 20 percent of service providers and program administrators use it frequently.

Smaller and more remote communities have challenges with adequate services in part due to the funding constraints and recruitment/retention issues of qualified personnel.

According to survey respondents, the main gaps in meeting communities' needs for Home and Community Care services consisted of the following:

- Lack of resources causing gaps in services or limiting service delivery, including staff shortages (including nurses, personal care providers and other human resources). Respondents touched on issues of access, lack of training, hiring, turnover and retention, especially in the case of remote communities. Some respondents also explained that having minimal staff means people have to cumulate different roles, which can hinder efficient delivery. Most comments pertaining to underfunding also related to staffing needs. Respondents referred to demographic shifts and new/higher demand (e.g., increased complexity of cases, increased co-morbidity, more mental health cases, addiction, etc.) as increasingly challenging to address with limited resources.

- The second most commonly identified gaps related to communication and coordination with other stakeholders, including gaps in communication with physicians, local hospitals and regional health authorities, namely regarding discharge planning and access to physicians. A few respondents mentioned challenges in communicating with families and clients themselves (e.g., gaps in support and challenges in compliance, language barrier).

- Respondents also noted gaps in terms of specific services, namely respite and palliative care, allied health services, wound care/clinical home care and mental health services. Some mentioned gaps in access to supplies (e.g., intravenous, medication). Respondents also noted that delivering services during business hours was restrictive, especially with regards to palliative care.

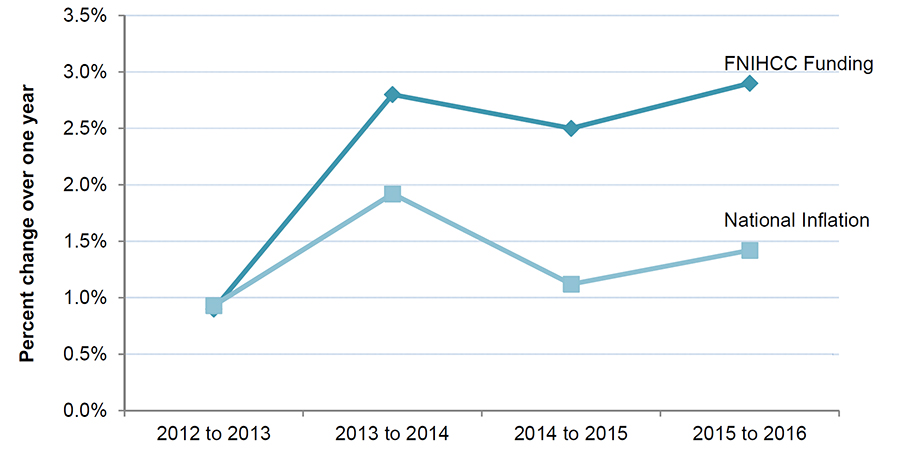

Funding for direct service provision has been increasing year over year at a rate approximately double the annual rate of inflation (Figure 5), and this growth rate is generally consistent with the growth rate of health care spending in Canada.Footnote 11 However, it is important to note that this is within the context of increasing complexity of needs, a competitive environment to recruit and retain health care workers, overall increasing health care and infrastructure costs, and demand for FNIHCC services that is widely expected to increase dramatically.

Figure 5: Rate of annual funding increases for FNIHCC exceeds the national inflation rate

Description of Figure 5: Rate of annual funding increases for FNIHCC exceeds the national inflation rate

Figure plots two lines showing percent change over one year in each of the four years from 2012-13 to 2015-16. The line representing FNIHCC funding moves from 1, to 2.8, to 2.5, to 2.9 percent. The line representing the national inflation moves from 1, to 2, to 1.1, to 1.4 over the same time period.

The vast majority of survey respondents felt that clients are having their needs generally or mostly met. However, there is a need to systematically assess the current demand and project it over the coming decade to better anticipate current and future needs.

Overall, however, this program was credited by interviewees as enabling clients to stay in their homes and communities more often and for longer than would have been possible without it, and ultimately as strengthening the quality of life of clients.

Another key contribution to improving the quality of life of clients was the assistance that is provided by FNIHCC staff in helping them and their families navigate various aspects of the health care system. This was highlighted as particularly important and necessary for many clients and families given the complex systems and challenges in understanding the interplay between the services received in the community and those provided by other institutions and organizations under provincial health systems.

According to the respondents, factors detracting from clients' needs being fully met include:

Staffing

- Recruitment and retention (including nurses, personal care providers and other human resources) primarily due to remoteness;

- Lack of training; and

- Minimal staff results in existing staff taking on multiple roles, which can hinder efficient delivery.

Increasing Demand

- Demographic shifts resulting in increased complex care needs, increased co-morbidity, more mental health cases, addiction, etc., which are difficult to address with limited resources;

- Gaps in specific services such as respite and palliative care, allied health services, wound care/clinical home care, and mental health services;

- Some gaps in access to supplies and equipment (e.g. intravenous, medication); and

- Delivering services during business hours is restrictive, particularly for palliative care.

Communication and Coordination With Other Stakeholders

- Gaps in communication with physicians, local hospitals and regional health authorities, namely regarding discharge planning and access to physicians; and

- Some challenges in communication with families and clients themselves (e.g. gaps in supports, language barriers).

Plateauing Funding Levels

- Funding levels have not significantly increased since the program inception approximately 20 years ago, however, Budget 2017 committed an additional $184.6 million over five years; and

- Overall increasing health care and infrastructure costs. Notably however, according to ISC's 2018-19 Departmental Plan, there was an intention for new investments in modern First Nation infrastructure to result in the design, expansion, and renovation of health facilities, as well as expanded access to eHealth solutions and the adoption of remote presence technologies (e.g. innovative use of robotics and portable devices).

Housing Conditions

- Existing housing conditions (e.g. major repairs, water quality) impact the safety and effectiveness of service delivery by adding additional needs for the client that would be less necessary in a home in good condition; and

- Approximately one-quarter of First Nations and Inuit people live in over-crowded houses (compared to three percent of the general Canadian population).Footnote 12

Additionally, a reported major gap is the lack of long-term care facilities in communities, which has a direct impact on the demand for FNIHCC services and supports as the program attempts to "fill-in" for this gap where possible.

Aspects of the program design that were identified as appropriate and contributing to achieving expected results included:

- Increased devolvement of the program to the community;

- Emphasis on key areas of service delivery ("essential services") within which there are opportunities for alignment with community priorities;

- Increased collaboration between FNIHCC, tribal councils, communities, and regional programming; and

- Role of FNIHCC staff in coordinating and managing care as well as making linkages and referrals to other services.

Areas for program improvement included:

- Overall communication, collaboration and coordination between national (FNIHB Headquarters) and regional levels (regional offices, provincial health systems, Indigenous organizations);

- Current funding amounts and allocations do not necessarily reflect need, changing population and changing provincial practices. Additional funding and options for training, particularly for personal care providers, are expected to directly improve the quality of services provided; and

- Extending FNIHCC services beyond the standard workday, including weekends. This is particularly important as services expand into different areas, including palliative and end-of-life care, respite services, and complex cases under Jordan's Principle.

Despite the efforts to devolve FNIHCC to communities, the majority are funded through setFootnote 13 funding arrangements. Exceptions include Saskatchewan, where 96 percent of funding is distributed in blockFootnote 14 arrangements, and the Atlantic region, where 70 percent of funding is distributed in flexibleFootnote 15 arrangements. This method of funding may have a negative impact on the federal government's goal of reconciling with First Nations and establishing nation-to-nation relationships given that its design is counter to self-determination and autonomy of governance.

The Department collects a large volume of data for FNIHCC. Survey respondents expressed some concerns about the reporting tool, the Electronic Service Delivery Reporting Template. Reported limitations include: not tracking outcomes or useful indicators like re-hospitalization within 30 days; the degree of rigorously tracked data (e.g. changing status to discharge, levels changing from acute to palliative); data quality issues due to input issues at the community end; and communication issues between regions and Headquarters.

3.6 Coordination and Integration

Finding 6. FNIHCC coordinates and collaborates with other programs and services at both local and regional levels. In some communities, FNIHCC and the Assisted Living programs have been integrated from a service delivery perspective.

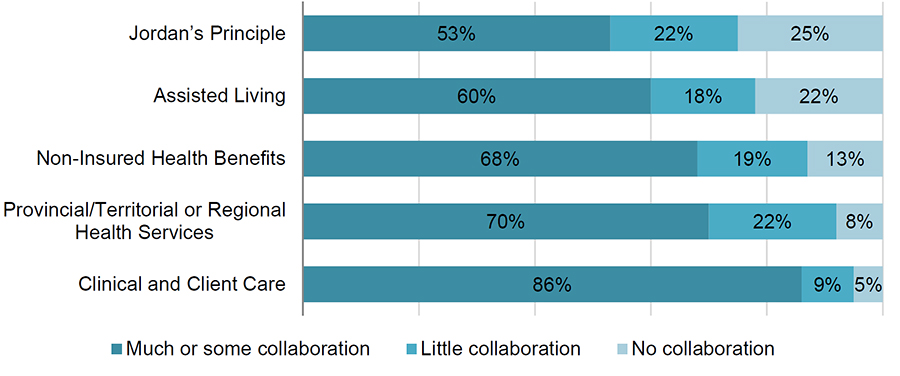

FNIHCC is tied closely to other health and social programs. Health directors and direct service delivery staff reported the level of collaboration and coordination across programs,Footnote 16 see Figure 6:

Figure 6: A significant majority of respondents viewed FNIHCC as collaborative with other health and social programs

Description of Figure 6: A significant majority of respondents viewed FNIHCC as collaborative with other health and social programs

Figure uses a bar graph to plot the proportion of interviewees seeing much or some, little, or no collaboration between 5 program areas. From much some, to little, to no collaboration, the graphic shows 53, 22 and 25 percent, respectively for Jordan’s Principle; 60, 18, and 22 percent, respectively for Assisted Living; 68, 19, and 13, respectively for Non-Insured Health Benefits; 70, 22 and 8, respectively for Provincial/Territorial or Regional Health Services; and 86, 9 and 5, respectively for Clinical and Client Care.

Respondents to the survey were also asked what coordination mechanisms they currently use with each of the other programs/initiatives, and how they could be improved. A summary of these are presented in Table 2. Overall, there are some common mechanisms; however, it should be noted that some of the suggested improvements are specific to each initiative.

The 2013 evaluation of FNIHCC reported that in communities where both FNIHCC and Assisted Living were formally integrated, delivery efficiency increased due to improved coordination, improved assessments and case management, and more targeted funding to address needs and staff training. Almost unanimously, First Nations administrators and ISC staff reported that most clients receiving services from one program also receive services from the other. Integration of FNIHCC and Assisted Living at the community level also resulted in more appropriate hours of service provided and increased responsiveness to client needs.

| Service | Current Mechanisms | Potential Improvements |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical and Client Care Program | Information sharing, case management and joint planning, as well as referrals, meetings and shared resources. Most reported existing channels of communications (e.g., fax, email, phone, etc.) | User-friendly electronic tools (e.g., electronic charting, common emergency management response platform, electronic assessment tool, etc.). Other suggestions: collaboration on discharges and case management, multi-disciplinary team meetings, and increased resources to deliver the adequate level of services. |

| Non-insured Health Benefits (NIHB) | Channels of communications (e.g., email, fax, phone), reported information sharing, and explaining that Home and Community Care can support access to NIHB (e.g., help in making applications, pursuing authorisations and confirmations, etc.). A few respondents explained that NIHB funds support certain aspects of service delivery and client care. | Most comments pertained to the timeliness of NIHB request approvals. Respondents felt that the processes are cumbersome, complex and should be streamlined. Several respondents suggested better communication from NIHB (e.g., regular updates, clear information, straightforward guidelines, and feedback on refusals). Respondents also felt that coverage should be increased to allow clients to access medication, supplies and specific services. |

| Provincial/Territorial or Regional Health Services | Existing communication channels (e.g., fax, email, phone, etc.) and information sharing mechanisms, including meetings. Some mentioned case management and discharge planning to some extent, and a few respondents mentioned co-training | Direct contact, improved information sharing (including better electronic resources) and more training/information sessions. The issues of case management and discharges were mentioned often. Several respondents felt that provincial service providers have a poor understanding of the Home and Community Care Program and of First Nations realities in general, which makes cooperation difficult. |

| Assisted Living Program | Referrals, common case management, information sharing and joint planning. In some instances, respondents explained that the two programs are administered or delivered jointly by the same staff. | Centralize/streamline/merge the two programs (alternatively, a few respondents felt the distinction between the two programs should be made clearer). Several respondents recommended expanding and improving funding for staffing, training and services under the Assisted Living Program in order to better meet needs. Several respondents remarked that Assisted Living is not available in their area, but would be beneficial. |

| Jordan's Principle | Referrals/support in application and case management. Some described shared resources and direct relationships. A few respondents noted that staff members coordinate on relevant issues. A few mentioned that the two sectors are integrated and described close collaboration on specific cases. | More information on the program (e.g., awareness campaign, training, information sessions), on ways it can be beneficial to Home and Community Care clients and on how to access it. Respondents noted that this is a new initiative that is still being put together and implemented |

Source: Survey of Health Directors and Home and Community Care Staff |

||

In some instances, the FNIHCC and the Assisted Living programs are administered or delivered jointly by the same staff in the community. As shown in Table 3, six of the 21 services provided between the two programs overlap.

| Eligible Services/Supports | Assisted Living | FNIHCC |

|---|---|---|

| Home care nursing services | Provided | |

| Personal care services (bathing, grooming) | Provided | |

| Shopping | Provided | |

| Rehabilitation and other therapies | Provided | |

| Access to medical equipment and supplies/provision of specialized items for client needs within home/care setting | Provided | |

| In-home mental health | Provided | |

| Wellness and fitness | Provided | |

| Attendant care | Provided | |

| Group care | Provided | |

| Menu planning | Provided | |

| Ironing | Provided | |

| Mending | Provided | |

| Carrying wood | Provided | |

| Minor home maintenance | Provided | |

| Non-medical transportation | Provided | |

| Adult daycare/programs | Provided | Provided |

| In-home/short-term respite care | Provided | Provided |

| Household cleaning | Provided | Provided |

| Meal preparation | Provided | Provided |

| Meal programs | Provided | Provided |

| Laundry | Provided | Provided |

Survey and interview participants suggested that the aging population has been a significant change impacting their caseloads. FNIHCC staff report that because FNIHCC helps the aging population be more independent and remain in their homes longer, this increases the need for non-medical Assisted Living services, such as meal preparation, cleaning, and transportation.

In cases where the programs were administered separately, there was regular communication between Assisted Living and FNIHCC in-home workers and their respective band administrators to ensure individuals were recommended for assessments if they were observed to need services that one program or the other was not able to provide.

The degree of integration of Assisted Living and FNIHCC varied by community. According to the survey, respondents from Ontario (39 percent) and Manitoba (54 percent) were the least likely to report some or much collaboration between FNIHCC and Assisted Living compared to other regions (Atlantic – 100 percent; Quebec – 93 percent, and Alberta – 69 percent). Some communities pooled the funding from both programs in order to provide the continuum of services a given client may need. In those cases, First Nations reported services separately under one program or the other, as accurately as possible, but with a largely arbitrary distinction. In other communities where there was a strong separation between the two programs, staff salaries were paid from each program separately, and the band had two separate software programs to manage the accounting.

Regardless of individual approaches to delivering the two programs, it is clear that either Assisted Living funding should broaden its eligible activities, or that the funding formula should be more flexible to account for unique circumstances in each community. Overall, there is a desire for a centralized, streamlined, or formally integrated approach of the two programs. Conversely, other respondents reported that if the programs remain separate, the distinction between the two should be made even clearer. All communities desired the flexibility required to deliver seamless responses to personal care needs.

Survey respondents reported that coordination between FNIHCC and all other programs should be improved, primarily through increased communication across all parties.

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

FNIHCC plays an important role in contributing to a better quality of life for clients, families and communities. The importance of remaining and healing in, and being able to contribute to, one's community while receiving the necessary health services and supports, cannot be overstated.

For many communities, Home and Community Care services and supports are the hub or connecting factors between various types of care, including hospitalization, longer-term care, and palliative/end-of-life care. But smaller and more remote communities have more challenges with quality in part due to the funding constraints (sufficiency of funds) and recruitment/retention issues of quality personnel.

Demand for FNIHCC services is expected to increase, while funding for the program has not increased significantly. This trend will result in an increased need for managing and coordinating care, linking with other professionals and services, training for FNIHCC staff (particularly for personal care providers), and resources for direct client care. Distinct factors and trends unique to First Nations and Inuit communities should be considered in assessments of this predicted increasing need, such as higher rates of chronic disease, greater challenges with various social and infrastructure determinants of health, and the importance of community.

The program has increased its level of coordination with other programs and services at both local and regional levels. There is noted overlap between FNIHCC and the Assisted Living Program. In some communities, the two programs have been integrated from a service delivery perspective.

The Home and Community Care Program's relatively high devolvement to communities is viewed as enabling communities to administer the program in a way that ensures alignment with their own priorities. The program objectives also align with the current federal government priorities – which include closing the gaps in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities and to implement the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's recommendations.

It is therefore recommended that ISC:

- Develop a strategy to measure current and prospective demand of services relative to capacity to provide services, in order to better inform policy directions on the extent of need as well as the coverage of different types of services;

- Better support communities in the training of personal care providers and to address issues of recruitment and retention of qualified FNIHCC personnel;

- Work with communities to develop communications strategies to improve coordination and communication with provincial/territorial/regional health services; and

- Where desired by communities, provide more flexible funding options that cover the spectrum of services currently available through both the FNIHCC and Assisted Living Program, including working with communities who wish to move from set to flexible funding arrangements to better manage services in the long term.

Appendix A: Evaluation Questions and Methodological Notes and Limitations

Evaluation Core Issues and Evaluation Questions

| Relevance | |

|---|---|

| Continued Need for Program: Assessment of the extent to which the program continues to address a demonstrable need and is responsive to the needs of Canadians. | 1. What are the current and emerging needs for home and community care services in First Nations and Inuit communities? |

| Alignment with Government and First Nations and Inuit Priorities: Assessment of the linkages between the program objectives and (i) federal government priorities; and (ii) departmental strategic outcomes; and (iii) First Nations and Inuit priorities. | 2. Is the program aligned with federal government priorities and departmental strategic priorities/outcomes? Is the program aligned with First Nations and Inuit priorities? |

| Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities: Assessment of the role and responsibilities for the federal government in delivering the program. | 3. Are the program's activities aligned/congruent with the federal government and the Department's jurisdictional and/or mandated roles and responsibilities? |

| Performance | |

|---|---|

| Achievement of Expected Outcomes: Assessment of progress toward expected outcomes as detailed in the program logic model. | 4. To what extent has the Home and Community Care program achieved its intended outcomes? 5. Is the program design appropriate for achieving expected program results? 6. To what extent has the program improved coordinated and seamless responses to home and community care need? |

| Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy: Assessment of resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes, including comparison to existing or hypothetical program design alternatives. Assessment of the extent to which there is appropriate performance measurement in place. | 7. Has the program undertaken its activities in the most efficient manner? 8. Are performance data being collected and reported? If so, is this information being used to inform senior management/decision makers? |

Research Methods:

Document and File Review - An extensive list of documents was prepared, and each was reviewed. There were approximately 85 key documents and websites that provided information for the evaluation.

Administrative Data Review - The program manages two databases where information regarding service delivery and resources are tracked: The Electronic Service Delivery Reporting Template contains client and provider information. Data is inputted at the individual-record level and then automatically aggregated during the upload process by sex and nine age categories; and The Electronic Human Resources Tracking Tool, contains information on full-time equivalents providing client services by source of funding and by application. The data available from these were reviewed for the evaluation along with financial data made available from Health Canada's Chief Financial Officer Branch regarding program funding and expenditures.

Key Informant Interviews - The purpose of the key informant interviews was to collect in-depth qualitative information on the FNIHCC evaluation issues and specifically to address gaps or clarify evidence from other methods. The information collected included opinions, descriptions, interpretations, and examples. Interviews were conducted with 55 representatives, including FNIHCC personnel at Headquarters and the regions, representatives from Indigenous communities delivering FNIHCC, national and regional Indigenous organizations, territorial and provincial representatives, and home care researchers and associations.

Web-based Survey – an online survey of Indigenous communities delivering FNIHCC was undertaken. Respondents were primarily health directors and/or Home and Community Care coordinators and nurses. There were 131 respondents to the survey, representing a 31 percent response rate.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Limited information available on the health status and specific health needs of Inuit, and limited participation by Inuit organizations in the evaluation | Findings on the need for program based on health status are focused more on First Nations people living on‑reserve, which may not be applicable to Inuit | Where possible in presenting findings, we have attempted to clearly indicate to whom the findings apply, and to identify where gaps remain. We have also attempted to gather information through documents where available (e.g., territorial annual reports). |

| The perspective of FNIHCC clients was not directly obtained using any of the methods selected for the evaluation, as these perspectives have been obtained from the First Nations Regional Health Survey. | The client perspective was not obtained for the evaluation. | Where relevant, we have indicated when the findings do not include the perspectives of clients directly. In some cases, we have been able to consider information from additional sources such as interviews with Indigenous organizations, and document reviews where available. |

| The evaluation team was unable to interview the number of community representatives initially planned. | The detailed qualitative-based perspectives of community representatives may not be fully represented in the evaluation findings. | We were able to conduct a survey with a more representative sample of respondents. In addition, we were able to interview various regional Indigenous organizations and some representatives from the First Nations Health Technicians Network. |

| Changing context for federal priorities given the change in government. | The evaluation period occurred during a change of government. This has resulted in changing priorities for some of the areas covered by the program such as addressing the calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, and increased resources to address health disparities for Indigenous Peoples and other Canadians. | Relevance of the Program was assessed for two time-periods: one period with the evaluation scope, and the other with current priorities to assist in the development of forward-looking recommendations. |

| Gaps in administrative data | Complete data set for all years covered by the evaluation is not available | We have emphasized the use of the most recent three years of data available and indicated where necessary the limitations of the data available |

| Response rate for survey and quality of survey frame. The 31 percent response rate is in keeping with similar surveys of communities. There was one region for which the survey frame was incomplete (i.e., Saskatchewan) | The survey results may not be representative of all community staff delivering FNIHCC services and supports. | We have focused on providing overall results from the survey and limited the number of sub-analyses given the challenge with sample size and response rate. |

Appendix B: Regional Funding Breakdown (Actual)

| Region | Year | Grants and Contributions |

Internal Expenditures (operations and maintenance) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic | 2014-15 | 5,522,269.00 | 328,450.48 | 5,850,719.48 |

| 2015-16 | 5,637,573.00 | 210,137.25 | 5,847,710.25 | |

| 2016-17 | 5,786,042.00 | 583,506.85 | 6,369,548.85 | |

| 2017-18 | 6,642,975.00 | 664,989.21 | 7,307,964.21 | |

| 2018-19 (Not Final) |

7,214,936.00 | 313,221.32 | 7,528,157.32 | |

| TOTAL | 30,803,795.00 | 2,100,305.11 | 32,904,100.11 | |

| Quebec | 2014-15 | 14,133,847.00 | 461,104.97 | 14,594,951.97 |

| 2015-16 | 14,513,392.00 | 413,297.03 | 14,926,689.03 | |

| 2016-17 | 14,987,984.00 | 515,808.56 | 15,503,792.56 | |

| 2017-18 | 16,873,610.00 | 531,073.76 | 17,404,683.76 | |

| 2018-19 (Not Final) |

18,099,749.00 | 289,223.84 | 18,388,972.84 | |

| TOTAL | 78,608,582.00 | 2,210,508.16 | 80,819,090.16 | |

| Ontario | 2014-15 | 20,518,415.00 | 600,200.69 | 21,118,615.69 |

| 2015-16 | 21,233,448.00 | 482,863.18 | 21,716,311.18 | |

| 2016-17 | 21,643,810.00 | 814,685.94 | 22,458,495.94 | |

| 2017-18 | 23,276,319.00 | 685,306.29 | 23,961,625.29 | |

| 2018-19 (Not Final) |

24,992,400.00 | 252,473.00 | 25,244,873.00 | |

| TOTAL | 111,664,392.00 | 2,835,529.10 | 114,499,921.10 | |

| Manitoba | 2014-15 | 19,460,545.00 | 408,842.55 | 19,869,387.55 |

| 2015-16 | 20,147,543.00 | 397,846.31 | 20,545,389.31 | |

| 2016-17 | 20,516,196.00 | 509,879.62 | 21,026,075.62 | |

| 2017-18 | 23,377,665.00 | 712,233.47 | 24,089,898.47 | |

| 2018-19 (Not Final) |

26,166,611.00 | 311,430.37 | 26,478,041.37 | |

| TOTAL | 109,668,560.00 | 2,340,232.32 | 112,008,792.32 | |

| Saskatchewan | 2014-15 | 15,288,823.00 | 922,479.75 | 16,211,302.75 |

| 2015-16 | 15,579,406.00 | 896,513.42 | 16,475,919.42 | |

| 2016-17 | 16,071,670.00 | 925,585.03 | 16,997,255.03 | |

| 2017-18 | 17,703,522.00 | 1,088,672.78 | 18,792,194.78 | |

| 2018-19 (Not Final) |

19,454,950.00 | 722,948.50 | 20,177,898.50 | |

| TOTAL | 84,098,371.00 | 4,556,199.48 | 88,654,570.48 | |

| Alberta | 2014-15 | 14,090,874.00 | 1,198,639.65 | 15,289,513.65 |

| 2015-16 | 14,388,840.00 | 1,085,080.56 | 15,473,920.56 | |

| 2016-17 | 15,188,021.00 | 1,198,111.97 | 16,386,132.97 | |

| 2017-18 | 16,623,752.00 | 1,521,666.64 | 18,145,418.64 | |

| 2018-19 (Not Final) |

18,340,310.00 | 1,161,491.33 | 19,501,801.33 | |

| TOTAL | 78,631,797.00 | 6,164,990.15 | 84,796,787.15 |