Evaluation of the Assisted Living Program

July 2019

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

PDF Version (239 Kb, 25 Pages)

Table of contents

Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| ESDPP |

Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships |

| FNIHCC |

First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program |

| ISC |

Indigenous Services Canada |

Executive Summary

The Evaluation of the Assisted Living Program started in the spring of 2018, and covered the period from the completion of the last evaluation (2008-09) to 2017-18. It was conducted using commentary from 28 key informant interviews with Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) staff from all regions and Headquarters, as well as various non-governmental and Indigenous organisations, a series of on-site case studies, a review of administrative data, and was complemented by data in a survey conducted for the evaluation of ISC's First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program.

This evaluation finds that the increasing needs and growing number of clients, compounded with increasing funding pressures, present growing challenges to First Nations in the provision of sufficient amounts of service. The Assisted Living Program has run progressively higher deficits in each year between 2014-15 and 2017-18, with budgets decreasing and expenditures increasing, yet participants in this evaluation indicated significant difficulties meeting the needs of clients, particularly with respite care, and keeping elders in their communities.

There is a strong desire to build capacity in communities, but there are significant difficulties doing so, particularly in the areas of recruitment, retention and training. Where First Nations are well positioned to handle administrative overhead and training costs, it is typically from other sources of revenue, thus creating an inequity between communities with reliable revenue streams other than the federal government and those without. It also puts considerable pressure on communities to cover these costs as it is often at the expense of funds for direct service provision.

In general, the current approach to program funding does not advance self-determination of communities. While generally valuable in terms of providing services and keeping many individuals in their community, there is room for improvement in this regard.

There is limited merit in the policy requirement for First Nations to align eligibility and rates to reference provinces. First, there are reasons First Nations may consider standards that are different from provincial ministries, where certain standards applicable on-reserve may be more applicable. Secondly, compelling a First Nation to apply rates and eligibility criteria of the reference province assumes the appropriateness and applicability of those criteria on-reserve, which is often not an appropriate assumption. The needs are often far greater and more complex on-reserve, and there are additional contextual issues to consider, such as an absence of broader wrap-around services, housing, transportation and infrastructure issues that are more prevalent on-reserve.

In examining the efficiency and long-term sustainability of the program, this evaluation found that the achievement of outcomes would be further supported by capital funding for minor home renovations and, even more substantially, for building long-term care homes on-reserve where feasible. Investments in long-term care facilities would better enable clients to stay in their homes and communities longer – a key objective of the program. As this is outside the purview of Assisted Living and rests with ISC's Infrastructure programs, collaboration would be needed to address this.

Additionally, this evaluation found that the Assisted Living, and First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care programs operate along a continuum. While services have mostly clear distinctions, separate program funding within ISC is somewhat impractical and has limited merit. There is some overlap in services provided, and significant overlap in terms of administration of the services, and of the clients who use them. The integration of these services along a continuum of care has shown promise for effective service provision and efficiency where it has been implemented, and has been a consistent recommendation in reviews conducted of these programs.

It is therefore recommended that ISC:

- Where desired by communities, provide more flexible funding options that cover the spectrum of services currently available through both the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care, and Assisted Living programs, including working with communities who wish to move from set to flexible funding arrangements to better manage services in the long term.

- In the short term, update program guidance to further clarify which services are eligible for funding, then develop and implement a communications plan to disseminate this revised guidance to First Nations administrators of the Assisted Living Program in all regions.

- Develop a strategy to measure current and prospective demand of services relative to capacity to provide services, in order to better inform policy directions on the extent of need as well as the coverage of different types of services.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Assisted Living Program

Project #: 1570-7/16131

1. Management Response

This Management Response and Action Plan has been developed to address recommendations resulting from the Evaluation of the Assisted Living Program, which was finalized by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement, and Review Branch.

The Assisted Living Program recognizes the findings included in the evaluation regarding the relevance and performance of the program. Specifically:

- The increasing needs and growing numbers of clients, compounded with increasing funding pressures, present growing challenges to First Nations in the provision of sufficient amounts of service;

- There is limited merit in the policy requirement for First Nations to align eligibility and rates to reference provinces;

- Achievement of outcomes would be further supported by capital funding for minor home renovations and, even more substantially, for building long-term care homes on-reserve where feasible; and

- Assisted Living and Home and Community Care operate along a continuum. While services have mostly clear distinctions, separate program funding within ISC is somewhat impractical and has limited merit.

The evaluation provides three recommendations to improve the design and delivery of the Assisted Living Program. All recommendations are accepted by the program and the attached Action Plan identifies specific activities to move towards meeting these recommendations.

The Department will proceed with implementing a three-year staged response to co-develop and implement operational and policy improvements to the Assisted Living Program. An annual review of this Management Response and Action Plan will be conducted by the Departmental Evaluation Committee to monitor progress and activities.

The staged approach recognizes program complexities and provides time to engage First Nations partners and others in a meaningful co-development process. This approach will also help ensure that any actions taken complement broader Government of Canada initiatives (e.g. New Fiscal Relationship, reduction in reporting burdens), initial thinking with the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program (FNIHCC) on the development of a continuing care strategy, the Government of Canada response to the Report of the Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs entitled "The Challenges of Delivering Continuing Care in First Nation Communities", or changes to complementary initiatives and programs (e.g. Jordan's Principle, Income Assistance, and infrastructure and housing programs).

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Where desired by communities, provide more flexible funding options that cover the spectrum of services currently available through both the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program and Assisted Living programs, including working with communities who wish to move from set to flexible funding arrangements to better manage services in the long term. | We do concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Assistant Deputy Minister, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships (ESDPP) | Start Date: April 2019 |

Assisted Living has already transitioned most of its one-year agreements from set to flexible funding approaches. However, we agree that where desired and where community General Assessments support, communities should be supported to move from flexible funding arrangements to block and 10-year grant agreements. We also agree that additional flexibility can be gained through improving the alignment between the FNIHCC and the Assisted Living programs to provide a more comprehensive spectrum of services.

|

Director General of Social Policy and Programs Branch | Completion: March 2020 |

|

| * This action item has also been signed off on by the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch | |||

| 2. In the short term, update program guidance to further clarify which services are eligible for funding, then develop and implement a communications plan to disseminate this revised guidance to First Nations administrators of the Assisted Living Program in all regions. | We do concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Assistant Deputy Minister, ESDPP | Start Date: February 2019 |

We agree with the recommendation and recognize the importance of clear communication so that First Nations administrators understand which services are eligible for funding under the program.

Note: going forward, the interpretation guidance may be updated along the annual cycle of revision to the Program Guidelines based on feedback from recipient communities. |

Director General of Social Policy and Programs Branch | Completion: March 2020 |

|

| 3. Develop a strategy to measure current and prospective demand of services relative to capacity to provide services, in order to better inform policy directions on the extent of need as well as the coverage of different types of services. | We do concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Assistant Deputy Minister, ESDPP | Start Date: April 2019 |

We agree with this recommendation and intend to, over a two-year period, co-develop and implement a measurement strategy that will provide data on the current demand for services as well as allow for trend analysis that could be used with other data sources to support prediction of future demands. We intend to develop a regional engagement process in 2019-2020 and will subsequently revise our strategy as required to reflect the appropriate next steps based on our work with First Nations and other partners.

|

Director General of Social Policy and Programs Branch | Completion: April 2021 |

|

| * This action item has also been signed off on by the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch |

1. Introduction

The Evaluation of the Assisted Living Program commenced in the spring of 2018, and covered the period from the completion of the last evaluation (2008-09)Footnote 1 to 2017-18. It was conducted using commentary from 28 key informant interviews with Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) staff from all regions and Headquarters, as well as various non-governmental organisations and Indigenous organisations. Additionally, five site visits to First Nation communities were conducted in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec. A full analysis of recipient reports relating to the Assisted Living Program, as well as ISC internal data from communities, and financial data, were analysed. A simultaneous evaluation of ISC's First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program (FNIHCC) included a survey of 131 health directors and/or Home and Community Care coordinators and nurses. This survey included questions related to the Assisted Living Program, which were also used to inform the findings and conclusions of this evaluation. Notes on the intersection between these programs are noted throughout this report, and there are recommendations that implicate both.

The evaluation matrix is outlined in Appendix A.

2. A Note About This Report

While this report constitutes an evaluation of the Assisted Living Program, one objective of the evaluation was to situate the program within the broader context of community management of care needs, and clients having their needs met, irrespective of whether these needs fall directly within the purview of the existing Terms and Conditions of the program. Therefore, observations are made regarding the experience of communities and clients overall and often implicate programs outside the current purview of Assisted Living (i.e., Infrastructure). The evaluators felt it was important to examine issues from a community perspective and an ISC program lens more holistically, rather than isolating the particular parameters of the Assisted Living Terms and Conditions from broader contextual pieces. Thus, many of the observations in this report are not always an indication of the Assisted Living Program itself falling short of meeting needs, but rather of needs not being met, and a resultant need for ISC to look at its programming through a broader lens.

3. Background

The Assisted Living Program was created in 1983, using the same financial authorities as the Income Assistance Program, based on the notion that individuals accessing Income Assistance would require affordable home care supports. Funding is available to eligible individuals residing on-reserve (and in Yukon), regardless of Indian status or age.

The objective of the Assisted Living Program is that in-home, group-home and institutional care supports are accessible to eligible low-income individuals to help maintain their independence for as long as possible in their home communities. This residency-based program provides funding to First Nations, provinces and Yukon Territory on an annual basis through negotiated funding agreements for non-medical social supports, as well as training and support for service delivery so that seniors and persons with disabilities can maintain functional independence within their home communities.

For in-home care, adult foster care and institutional components, clients must be (i) ordinarily resident on-reserve; (ii) formally assessed by a designated social service or health professional using the care assessment criteria recognized by ISC as requiring one or more eligible supports; and (iii) be unable to obtain such services themselves, or access other federal or provincial/territorial sources of support, as confirmed by an assessment covering employability, family composition and age, and financial resources available to the household.

Eligible services are generally comprised of:

In-Home Care: provides funding support for non-medical support services, including: housekeeping, meal preparation, attendant care, adult care, meals on wheels, short-term respite for caregivers, non-health transportation, and more.

Institutional Care: reimburses for some expenses related to Type I and Type II care in designated facilities for adults.Footnote 2

Adult Foster Care: supervision and care for adults in a family-like setting who do not require 24-hour care but are unable to live on their own. Before client expenses in adult foster care can be reimbursed, eligible funding recipients must verify that the adult foster home charges provincial or territorial per diem rates, and operates according to the licensing or accreditation guidelines of the reference province or territory.

Disabilities Initiative: proposal-based program that supports projects intended to improve the coordination and accessibility of existing disability programs and community services to persons living on-reserve.

The operational processes, procedures, licensing and accreditation associated with a Firs Nation's delivery of Assisted Living must be consistent with those same processes in the reference province or territory. The program also funds training and support for service delivery.

The maximum amount of funding to be provided to a funding recipient community in a fiscal year is set out in the funding agreement signed by the funding recipient community.

4. Evaluation Findings: Impacts and Outcomes

4.1 Meeting Needs

Finding 1. The increasing needs and growing number of clients, compounded with increasing funding pressures, present growing challenges to First Nations in the provision of sufficient amounts of service.

The expected outcome for the Assisted Living Program, according to the 2016-17 Departmental Report on Plans and Priorities, is that in-home, group-home and institutional care supports are accessible to low-income individuals in need. The indicator is that 100 percent of clients whose social support needs were assessed have those needs met. Data from 2016-17 show the achievement of this indicator to be 97 percent. The 2018-19 data collection instrument was amended to allow administrators to report on whether there was no service provided, as a way to capture the extent of wait lists and service provision gaps. This amendment reflects what was heard unanimously by First Nation participants in this evaluation: that individuals who applied to receive services were often not able to receive the full amount of service hours or appropriate type of care for which they were assessed.

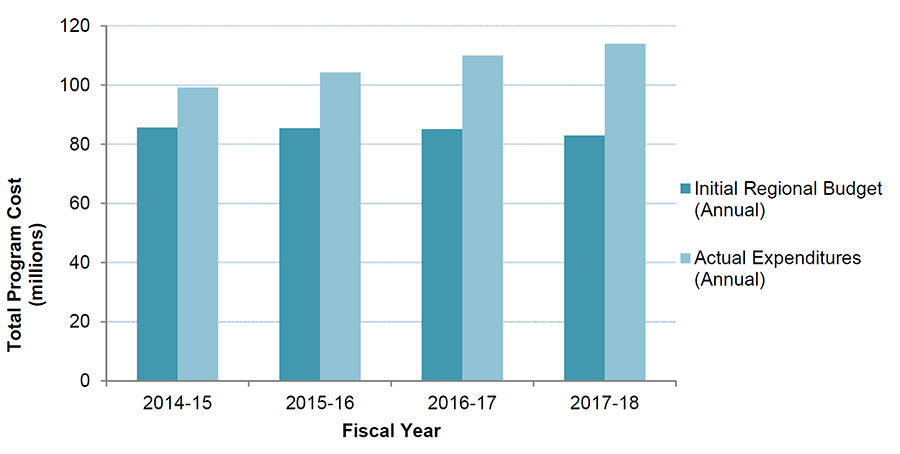

Over the past four years, the Assisted Living Program has increasingly run a deficit, as budgets have decreased somewhat, while actual expenditures have markedly increased (see Figure 1). A national funding allocation methodology exists; however, ISC regional offices have a high degree of autonomy in deciding how funding is calculated and provided. In the past, regional offices would reallocate funding internally if a particular program was short of funds. A recent Canadian Human Rights Tribunal Remedies Order concerning First Nations Child and Family Services ruled that Canada must "stop unnecessarily reallocating funds from other social programs, especially housing, if it has the adverse effect to lead to apprehensions of children or other negative impacts." A decision within ISC's Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector has prohibited social programs from reallocating funding internally from one program to another. It was felt by interviewees that this will likely compound funding pressures that recipients are already facing.

Ultimately, while budgets have decreased slightly from approximately $85 million in 2014-15 to just over $80 million in 2017-18, actual expenditures have increased from just under $100 million in 2014-15 to approximately $117 million in 2017-18. This shows a significant and growing incongruence between what the program is estimated to cost per year and what it actually costs.

Figure 1: While regional budget allocations have decreased over time, actual expenditures have increased.

Description of Figure 1: While regional budget allocations have decreased over time, actual expenditures have increased

Figure shows annual program budgeted expenditures (in millions of dollars) staying generally the same at about 82 million dollars per year between 2014-15 and 2017-18. These data points are plotted alongside annual actual expenditures, increasing steadily from approximately 100 million dollars in 2014-15, 105 million in 2015-16, 110 million in 2016-17 and 115 million in 2017-18.

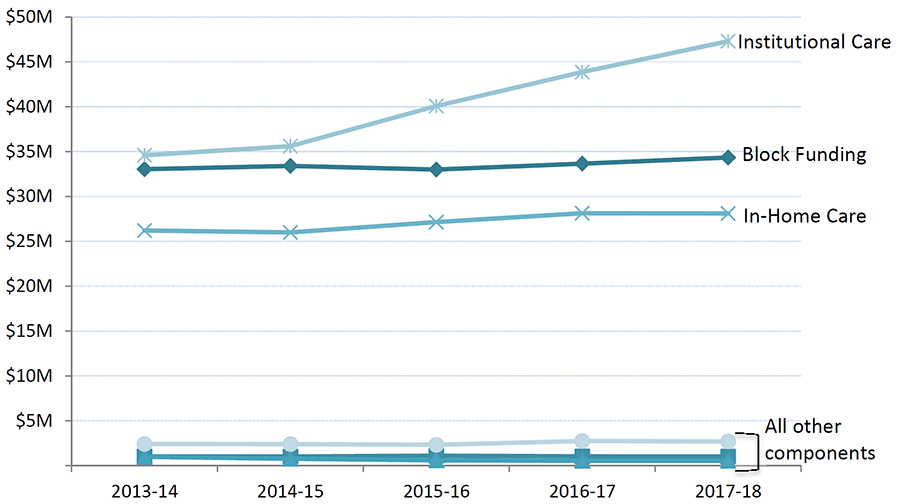

However, funding for block agreements, as well as the components of all other funding agreements (in-home care, foster care, service delivery, and the disabilities initiative) except institutional care have seen no growth in this time. The institutional care component has seen growth of nearly 37 percent in that time, and is responsible for the increase in total expenditures nationally (see Figure 2).

This increase in total expenditures is driven by trends in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Yukon, which have all seen massive increases in expenditures in institutional care, but not in other categories, which is not the case in other regions. In general, spending for in-home care has increased in the Alberta and Atlantic regions and decreased in British Columbia, and has remained unchanged elsewhere. Spending under block agreements for assisted living has only increased measurably in Quebec.

Figure 2: Funding for most components did not change from 2013-14 to 2017-18, with the exception of Institutional Care, which increased by 37 percent

Description of Figure 2: Funding for most components did not change from 2013-14 to 2017-18, with the exception of Institutional Care, which increased by 37 percent

Figure plots actual expenditures for institutional care, increasing gradually from 35 million dollars to 47 million dollars between 2013-14 and 2017-18. It shows expenditures for block funding steady over this time period at about 34 million dollars per year, generally steady for in-home care at about 27 million dollars per year, and steady at roughly 1 to 3 million dollars for all other expenditures over this timeframe.

In essence, current funding levels do not allow First Nations to provide the full amount of hours of care recommended in assessments. Although communities varied in the types and levels of unmet needs among their community members, regularly-cited needs that often go unmet included:

- Offering Assisted Living services on weekends;

- Providing support for out-of-home tasks, such as transportation and support for errands and day programs;

- Meeting the needs of higher-need clients or clients with challenging behaviours, such as addictions or brain injuries;

- Accomplishing all tasks that clients need help with in their homes, due to budget limitations resulting in insufficient service hours provided; and

- Funding palliative care and culturally relevant activities, including using traditional healers.

With current funding, if a band hires another administrator, it would result in less funding available for direct service hours to clients. Bands with the means to cover administrative costs like salaries are those with own-source revenue or large Band Support Funding allotments.

First Nation program administrators noted there were tight budget limitations to cover administrative costs such as efficient information technology assets. Respite is an eligible expenditure of the Assisted Living Program; however, Assisted Living administrators reported that, in most cases, communities do not have sufficient Assisted Living funding to pay for this service. Administrators reported that the entire in-home care portion of Assisted Living went towards paying for direct homemaking services such as meal preparation and cleaning. Most communities did not fund any respite. In one community, they funded respite through own-source revenue, while in other communities, families were expected to pay respite out of pocket. First Nation program administrators reported that not being able to offer funding for respite was resulting in a decrease in quality of service provision because of caregiver burnout.

Respite is also an eligible service in the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch's FNIHCC and via Jordan's Principle funding. The survey conducted for the evaluation of FNIHCC found that 63 percent of respondents reported an increase in demand for in-home respite over the past five years. Proposals from the first two years of Jordan's Principle funding reveal that four percent of requests are for respite. As of the writing of this report, ISC does not collect data on the reason for applying for respite via funding through Jordan's Principle, so any links to the Assisted Living Program cannot be drawn.

The impact of unmet needs varied among communities, with some reporting relatively mild inconveniences or challenges in these areas, while other communities reported not being able to provide sufficient services to ensure that elders were living in sanitary and safe conditions (e.g., not able to do laundry regularly, not able to provide meal preparation for appropriate and nutritious foods). In all communities, the underlying cause of these unmet needs was insufficient funding for all of the assessed needs for the in-home services portion of the Assisted Living Program.

Services provided through institutional care were less likely to have unmet care needs, largely because Assisted Living funding covers, in full, the per diem for residents of long-term care facilities off-reserve (when an individual does not have the means to do so). This differs from in-home care, where the provision of service hours is subject to available resources, and therefore a client receives an approved number of service hours, which may or may not equal the hours of service for which a client was assessed.

Although a resident in a long-term care facility funded by ISC always receives provincial-standard care, it was reported that there were several issues associated with cultural, social, and emotional wellbeing in relation to institutional care, specifically regarding off-reserve facilities. These concerns include:

- The distance from their home communities that frequently results in social isolation and poor mental and physical wellbeing;

- A void of First Nation perspectives on emotional and social wellbeing, such the opportunity to engage in traditional ceremonies like those undertaken when a loved one passes away; and

- Where a community lacks care facilities, many clients (mostly elders) will need to receive care off-reserve in institutions that lack cultural connection to their communities. While not the intention of institutional care, many interviewees drew parallels to residential schools, particularly for elders who were school children during the peak of that era.

Unique geographic and social challenges, such as severe weather and housing shortages in many First Nations, can create hurdles to providing specialized care in on-reserve facilities (e.g., foot care specialists, speech and occupational therapists that are required under provincial licensing standards). The costs to fly in these professionals to provide care on a monthly or biweekly basis can be prohibitive, and program funding formulas do not account for these differences among communities.

It has been found that the psychological and emotional trauma that stems from the residential school system can decrease a person's ability to care for a family member, meaning the role of in-home care workers may be particularly important in First Nations communities that have a population largely impacted by intergenerational trauma.

4.2 Community Capacity

Communities' capacity limitations were most commonly noted in the area of human resources; for example, long hours for band staff, hiring and retention of skilled workers, and providing upgrading and training to workers. Assisted Living administrators regularly faced a common dilemma: to hire another administrator to ease their workload would result in having less funding available for direct service hours to clients. Wherever this concern was raised, administrators reported choosing to provide services for clients. Bands with the means to cover administrative costs like salaries were those with own-source revenue or large Band Support Funding allotments.

Most communities struggled to recruit and retain staff to deliver Assisted Living services. With existing Assisted Living funding, communities were unable to offer competitive pay and benefits. Another challenge compounding the wage and benefits issue is the lack of housing on or near reserves requiring individuals to either pay high rents in a market where housing is scarce, or undertake long commutes to and from work daily. These challenges were also tied to, in some cases, a struggle for communities to offer services on weekends and evenings.

Training costs are also significant. The ongoing demographic change has led some program administrators to be concerned for the safety of homemakers, as the growing number of physically strong and unpredictable clients may pose a danger to them. Training for mental health and conflict management would be useful for homemakers to have, as most communities do not have the resources to send two homemakers to a client's home, which was cited as one of the only current protection options. In cases where communities were able to hire and retain staff to deliver services in clients' homes or long-term care facilities, an identified need was for training for staff to deal with specialized clients, such as those with addictions issues or acquired brain injuries. Some of the types of training that were desired among communities included:

- Fall prevention training;

- Nutrition and food safety;

- Identifying elder abuse and neglect;

- Crisis intervention and de-escalation skills;

- Skills needed to support individuals with cognitive challenges and mental health issues, including addiction; and

- Basic workplace safety training.

A number of administrators believed that training was not an eligible use of Assisted Living funding; others knew it was an available expenditure, but were restricted by costs. The inability to support training of workers, particularly in-home care workers, compounds challenges of attraction and retention, which can result in higher administrative costs due to staff turnover, and reduced continuity of care for clients. This can be especially important in communities or homes where elders are hesitant to allow strangers into their homes, and when working with individuals with dementia. Rates of dementia in Canada are increasing: in 2011, 750,000 Canadians were living with dementia, and that number is projected to double by 2030.Footnote 3 There is some evidence that the rate of dementia is increasing even faster in Indigenous seniors compared to non-Indigenous seniors.Footnote 4

4.3 Self-Determination

At the heart of the conversation about reconciliation between the Government of Canada and First Nations is control and self-determination. In essence, while there are many communities under block funding arrangements that can better determine their own priorities, the design of the Assisted Living Program (and all ISC social programs) continues a practice of defining and controlling the services of First Nations through program guidelines and terms and conditions for grants and contributions. The recent change from the former Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada to Indigenous Services Canada, and the associated move from program terms and conditions to services supports, may help improve the relationship between the Government of Canada and First Nations.

The value of the Assisted Living Program was reported to be very high. Many administrators demonstrated the commitment to the wellbeing of individuals by supporting their elders through the use of own-source revenue and other funding streams to supplement Assisted Living funding. Keeping elders in their home communities was such a priority for some communities that it was written directly into their community plans. One administrator in a community that did not have a facility on-reserve told evaluators that an elder who was brought to a senior's home off-reserve asked her, "Is this where I am going to die?".

The current dynamic of ISC as program agent and funder, and the First Nation as administrator, was sometimes reported as being misaligned with ISC's intended goal of supporting First Nations on the path of becoming fully self-determining. One Assisted Living administrator paraphrased a chief by stating: "We are just agents of delivery for the [federal] government; we are not self-governing. So I recommend that we look at programs based on First Nations' uniqueness. Policies cannot just be pushed down to the First Nations level for us to implement."

5. Evaluation Findings: Relevance and Program Design

5.1 Provincial Comparability

Finding 2. There is limited merit in the policy requirement for First Nations to align eligibility and rates to reference provinces.

While Assisted Living administrators acknowledged the value of provincial institutional care standards in terms of client safety and guaranteeing a certain level of care, some felt that limited funding prevented them from meeting the provincial standards required to license their on-reserve facility. For example, an on-reserve long-term care home in a community in Manitoba could not become licensed because it could not meet the provincial standard requiring that a nurse be on site 24 hours a day, seven days a week, due to a lack of housing and inability to provide competitive wages through the Assisted Living Program.

There is merit to considering other approaches to standards and regulations that are not provincial. For example, two communities visited during the site visits had facilities that were accredited by Accreditation Canada; one explained that they preferred to meet these standards because they felt those standards were "higher than provincial standards" and also because this particular community straddled multiple jurisdictions, so having a single standard to adhere to simplified their approach to care quality. It should be noted that the territory of Yukon does not have legislation dictating standards for institutional care, and therefore uses Accreditation Canada as its licensing body.

Provincial comparability issues do not just apply to standards, but also to the application of rates and eligibility criteria. To receive Assisted Living services, an individual must prove, through a financial means assessment, that he or she is unable to obtain such services without financial support. Some provinces (e.g. British Columbia) do not restrict these services to low-income individuals. Any person can receive a physical needs assessment and receive services, and the amount they owe is then decided on a financial means assessment.

Administrators felt that conducting financial means assessments tends to act more as an administrative barrier, rather than a tool to identify the individuals who are the most in need, particularly considering that most individuals living on-reserve have low incomes.

Since the Assisted Living Program was created in 1983, provincial and Yukon assisted living-type programs have gone through numerous changes. Today, most provinces and the Yukon aim to serve clients on a continuum of care, whereas this is only somewhat the case with current ISC programs. Up until 2017-18, the regional allocation methodology for funding was based on historical estimates and a small cost escalator. These historical estimates were based on provincial costs at the time, but have limited merit today. The regional allocation methodology for fiscal year 2018-19 has been adapted to allow regional offices to consider additional factors, such as a projection of expected clients and a cost escalator, which reflects the rate of inflation and industry-wide annual increases in the cost of delivering social support services. These adaptations may better reflect the reality of First Nations communities and may better support their delivery of the program.

Importantly, provincial comparability alone does not necessarily account for the reality on-reserve, and in particular the growing and evolving need. The population of First Nations people in Canada is expected to increase by 40 percent between 2006 and 2031, the bulk of that percentage being aged 60 or older, which is set to triple by 2031.Footnote 5 First Nations individuals aged 45-54 have reported frailty levels that are similar to the 65-74 age group in the non-Indigenous population.Footnote 6 Similarly in that age bracket, it is reported that 51 percent of Indigenous individuals have three or more chronic conditions, compared to 23 percent for the non-Indigenous populationFootnote 7, and dementia diagnoses are increasing faster in the Indigenous elderly population. The Indigenous population is expected to require health and social services approximately ten years earlier than the non-Indigenous population.

According to a survey conducted by Goss Gilroy Inc. for the evaluation of ISC's FNIHCC, many respondents noted that the aging population was a significant change impacting their caseloads. Respondents acknowledged that while FNIHCC helps the aging population be more independent and remain in their homes longer, this also increases the need for non-medical Assisted Living services, such as meal preparations, cleaning, and transportation. The same survey found that many respondents reported that requests have increased for services in general over the past five years.

Simultaneously, there will also be a growing need for supportive health services and chronic disease management at younger ages. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and autism diagnoses are becoming more prevalent in Indigenous youth. Program administrators working in communities also reported increasing behavioural and health problems stemming from opioid use. Difficulties associated with these diagnoses are typically magnified by other determinants of health such as poverty and poor housing. First Nations people living on-reserve are much more likely to reside in a home in need of significant repair [43 percent versus seven percent] and/or an overcrowded home [27 percent versus four percent] than non-Indigenous individuals.

A large number of younger individuals with increasing and changing behavioural diagnoses and social needs would be eligible for Adult Foster Care funding, which was reported as a significant need by every community visited for this evaluation. However, Adult Foster Care is currently only available in Quebec, British Columbia, and Yukon, with a very small amount provided in Alberta. The growing younger population with intellectual and behavioural needs does not necessarily require full-time, provincially-licensed foster homes but rather recreational or drop-in centres or more access to highly trained home care staff.

Assisted Living clients may face barriers or benefits depending on the province in which they live. For example, First Nation administrators often reported having difficulty attracting and retaining staff to provide Assisted Living services, which results in many communities relying on family to provide those services. Under policy in some provinces, a family member cannot be paid to provide in-home care services. Unsurprisingly then, such a rule may act to the detriment of clients on-reserve because of the higher likelihood of people being related to one another, leading to fewer available eligible workers to provide home care.

In terms of institutional care, program costs vary greatly across regions. In about half of the regions, off-reserve care costs more than it does on-reserve. In 2015-16, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan reported off-reserve institutional care costs higher than those on-reserve. Conversely, Quebec and British Columbia ISC regions had lower costs for residents in off-reserve institutions, and in Ontario and Alberta, costs were approximately the same.

5.2 Program Efficiencies

Links to Infrastructure

Finding 3. Achievement of outcomes would be further supported by capital funding for minor home renovations and, even more substantially, for building long-term care homes on-reserve where feasible.

In communities participating in this evaluation that did not have an on-reserve long-term care home, interviewees expressed a desire to build one. Program administrators also reported the desire for increased funding for minor home renovations. They argue that the costs of minor capital projects, such as converting a ground-floor room into a master bedroom or inserting a bath tub grab bar, outweigh the cost of moving someone to a long-term care facility, and such measures would also support the achievement of the program outcome by enabling a person to stay in their home for even longer. The argument that staying in home is more cost-effective than living in a long-term care facility is evidenced through Assisted Living financial data.

In 2016-17, the actual cost of Assisted Living nationally was approximately $111.8 million. Roughly 40 percent of total funding covers in-home care, and roughly 60 percent covers institutional care. There are 9,600 clients receiving in-home care supports through Assisted Living and 830 individuals living in long-term care facilities. As such, the estimated cost per year, per client for in-home care is $4,658, while the annual per client cost for an individual living in a long-term care facility is $80,819.

Where needs for adaptive home renovations are identified and feasible, this would likely be far more cost-effective than transferring an individual to a facility simply because there were physical limitations in the home that could have been addressed to promote greater independence. There is a considerable need to consider, both for the wellbeing and independence of clients, and for the overall cost-effectiveness of the program, the policies and approaches to better enable First Nations to provide adaptive renovations. Investments in long-term care facilities would better enable clients to stay in their homes and communities longer – a key objective of the program. As this is outside the purview of Assisted Living and rests with ISC's Infrastructure programs, collaboration would be needed to address this.

The goal of every community that participated in this evaluation is to have people stay in the community. The stated outcome of the Assisted Living Program supports this desire, however in practice, the struggle to hire and retain staff to deliver in-home care, and the limited means to run long-term care homes on-reserve (provincial licensing and capital costs), often results in elders being left with no other choice but to leave the community. The benefits of keeping elders in their own communities include: reducing language barriers that may result in inappropriate care, particularly for residents with dementia; a decreased risk of racism or degrading treatment; and a better retention of traditional identity and roles.

In cases where there is no long-term care home on-reserve, many interviewees drew parallels to the residential school system that those same individuals were subjected to as children. Program administrators explained that having funding for a capital project like building a long-term care facility or elders lodge in the community would be their preferred option as a means to further preserving the wellbeing of the individual.

Integration and Overlap with the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care Program

Finding 4. Assisted Living and FNIHCC operate along a continuum. While services have mostly clear distinctions, separate program funding within ISC is somewhat impractical and has limited merit.

Historically, Assisted Living was designed to be an income support program to enable those with low or no income to receive services. Today, in practice, it is more like a health program in that social and health supports are often integrated in First Nations communities. The original design of the Assisted Living Program is reasonable in theory; however, it has not kept pace with the changing realities of health and social needs of First Nations people living on-reserve, nor the evolving nature of these types of services off-reserve.

The 2013 evaluation of FNIHCC reported that in communities where the two programs were formally integrated, delivery efficiency increased due to improved coordination, improved assessments and case management, and more strategic funding to address needs and staff training. Integration of the two programs at the community level also resulted in more appropriate hours of service provided and increased responsiveness to client needs.

Across all communities, Assisted Living administrators reported that they had strong informal networks within the community for identifying elders and other adults who may be in need of services. In some communities, this was supplemented by having strong community health care coordination, particularly with FNIHCC. These networks supported administrators to assess new clients efficiently. All communities reported being able to assess a new client within a maximum of 72 hours, and often within 24 hours in cases of high need. It was reported by communities that, in cases when the programs were administered separately, there was regular communication between Assisted Living and FNIHCC in-home workers and their respective administrators in the community to ensure individuals were recommended for assessments if they were observed to need services in the home that one program or the other was not able to provide.

The degree of integration of delivery of Assisted Living and FNIHCC is typically based on administrative capacity in a given community. Generally, communities with lower capacity pooled the funding from both programs in order to provide the continuum of services a given client may need. When it is time to report, Assisted Living administrators explained that services were reported as accurately as possible, but the distinction was somewhat arbitrary given the number of clients receiving both types of service. In communities with higher capacity, the separation of the program funding and delivery was less of an issue. In some cases, staff salaries were paid from each program separately, and the band had two separate software programs to manage the accounting.

According to the survey conducted in 2018 for the evaluation of FNIHCC, respondents (nurses and long-term care administrators) from Ontario (39 percent) and Manitoba (53 percent) were the least likely to report some or much collaboration between FNIHCC and the Assisted Living Program compared to other regions (Atlantic – 100 percent; Quebec – 93 percent; Alberta – 69 percent). Respondents who reported much or some collaboration spoke mainly about referrals, common case management, information-sharing and joint planning. In some instances, respondents explained that the two programs are administered or delivered jointly by the same staff.

Although the division of Assisted Living and FNIHCC responsibilities was clear to virtually all Assisted Living administrators, several of them questioned whether having the programs separated from the point of view of funding was the most efficient way to accomplish the goals of both. Regardless of a given community's ability to manage the funding from both programs, almost unanimously, it was reported by First Nations administrators as well as ISC staff that most clients receiving one program would also be receiving services from the other, pointing to the important concept of a continuum of care that is widely discussed in literature.

Regardless of their individual approaches to delivering the two programs, all respondents believed that either Assisted Living funding should broaden its eligible activities, or that the funding formula should be more flexible to account for unique circumstances in each community. The survey for the FNIHCC evaluation found that many respondents desired a centralized, streamlined, or formally integrated approach of the two programs. For some administrators with fixed funding, they believed that they could better deliver the program if they had block funding.

Communities reported that the current design of each program is not as effective as it could be. An integrated approach to Assisted Living and FNIHCC would enable communities to better utilize funding to cover the continuum of needs, which their community members require. All communities desired the flexibility required to deliver seamless responses to personal care needs.

These findings on Assisted Living and Home and Community Care, and First Nations continuum of care in general, are not new. In 2009, the Evaluation of Income Assistance, National Child Reinvestment Benefit and Assisted Living made three recommendations related to the topic:

- "Consideration should be given to separating funding for Assisted Living's In-Home and Institutional Care and developing funding methodologies for each component of the program. Integrating Assisted Living In-Home into the Home and Community Care Program would move part way to achieving this objective;

- Program management in conjunction with Health Canada should consider the formal integration of the in-home care and community support component of the Assisted Living Program and Home and Community Care; and

- Program management in conjunction with Health Canada should consider jointly piloting integrated single access models of continuing care in regions across the country, and based on the results of these pilots, develop a longer term strategy for service integration and access."

Again in 2013, the last FNIHCC evaluation made the recommendation that:

"Health Canada should continue pursuing its negotiation with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) to achieve formal integration of the FNIHCC Program with the AANDC Assisted Living Program - In-Home Component to improve efficiencies in the delivery of home care services."

That these recommendations were never implemented may in part be the result of the fact that they were funded by two separate federal departments. Today, there is an opportunity to reconsider the feasibility of integration with both programs now under ISC. The Ministerial mandate letter, provided by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, focused on systemic change, particularly regarding delivery of health services to Indigenous peoples. The focus of the letter was to work closely with other federal departments to prioritize patient-centred, community based service delivery and returning control and jurisdiction back to Indigenous communities.

5.3 Jurisdiction and Communication

When asked about the division of responsibilities between the federal government and First Nation communities for the Assisted Living Program, unanimously, program administrators understood the role of ISC as the funder and First Nations as administrators of the program. Although the high-level responsibilities are clear, there is a breakdown in knowledge and communication at a practical level. During the research for this evaluation, a number of jurisdictional concerns were raised, many of them based on misinformation. It was widely reported that information is misinterpreted or miscommunicated because of a lack of communication between the federal government, provincial governments, and First Nations administrations.

A number of Assisted Living coordinators reported an erosion of trust based on the lack of communication with ISC regional offices on how Assisted Living funding levels are determined and distributed to First Nations administrations. This eroded trust was identified as a major barrier to building nation-to-nation relationships. Other communities expressed frustration over a perceived lack of transparency in terms of how funding decisions are made. It is possible that these concerns are caused by high staff turnover in ISC Headquarters, regional offices and in First Nations communities, which results in lost corporate knowledge.

The Data Collection Instrument for recipients of Assisted Living Program funding was a clear source of miscommunication with regional offices. It has changed numerous times over the past several years in a well-intentioned effort to reduce reporting burden. However, First Nations program administrators and ISC staff report that many communities continue to use outdated versions, likely because of a lack of communication between regional offices and First Nations band staff. This poses the risk of inaccurate information being submitted to ISC, or duplicated efforts for First Nations administrators who are told to resubmit information on the correct form. The data collection instrument for fiscal year 2018-19 includes an option for program administrators to report the number of needs or assessed hours that were not provided. Up until that revision, past data collection instruments did not include an option for program administrators to report on what services they were unable to provide, which has resulted in achievement of outcomes being overstated.

Some communities reported challenges in coordinating with provincial agencies to move elders to facilities that were located off-reserve. ISC requires that an assessment by provincial or regional health representatives be completed for institution-based care, to ensure that individuals who are being placed in facilities meet the same eligibility requirements as those living off-reserve. In some cases, participants in this evaluation felt that provincial or regional health workers seemed to lack the understanding that Type I and Type II care would still be paid for federally, even if services were delivered at a provincial facility; similarly, First Nations administrators felt that provincial or regional workers did not believe that it was their job to assess a federal client for entry into a privately-run facility.

In one region, Assisted Living administrators noted that the process of moving a client to a provincial facility could vary, and was reliant on the relationship that the First Nation had established with the regional health authority representative with whom they were in contact. Notably, this problem was not reported during the site visit in Saskatchewan, where there have been considerable efforts in recent years by ISC and the province to develop processes for care continuity and moving between jurisdictions. In regions where there is a strong relationship between the regional office and communities, communication is frequent, albeit informal.

There were also communication issues regarding eligible expenses, leading to a sentiment that ISC regional offices exert tight control over what is and is not allowable, where in fact it may be a question of available resources as opposed to policy. For example, transportation for non-medical purposes (e.g., errands), delivery of staff training, and support for social outings for seniors were items that First Nation administrations frequently believed to be 'not allowable' by ISC. When presented with this information, regional staff said they could not understand why the administrators believed these to be ineligible, and suggested that resource limitations may have been the issue.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The Assisted Living Program is valued for the level of service and care provided, and for promoting the independence of individuals in their homes and in their communities. However, First Nations are not given the autonomy or flexibility to provide a continuum of care and services most relevant to their needs and circumstances. While there are several areas that could take the form of evaluation recommendations, fundamentally, the first step is to change the approach of the Assisted Living Program to one that promotes the self-determination of communities and allows for a continuum of care.

It is therefore recommended that ISC:

- Where desired by communities, provide more flexible funding options that cover the spectrum of services currently available through both the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care, and Assisted Living programs, including working with communities who wish to move from set to flexible funding arrangements to better manage services in the long term.

- In the short term, update program guidance to further clarify which services are eligible for funding, then develop and implement a communications plan to disseminate this revised guidance to First Nations administrators of the Assisted Living Program in all regions.

- Develop a strategy to measure current and prospective demand of services relative to capacity to provide services, in order to better inform policy directions on the extent of need as well as the coverage of different types of services.

Appendix A: Evaluation Matrix

| Evaluation Area | Evaluation Question | Indicator (from 2017-2018 Performance Information Profile), where applicable |

|---|---|---|

| Desired Outcomes | To what extent are the supports provided by in-home, group-home, institutional care and other related initiatives, meeting the needs of low-income individuals in need who are ordinarily resident on-reserve? | Percentage of low income residents on-reserve who perceive a gap in their access to social support services |

| Percentage of institutional care clients in off-reserve facilities | ||

| Percentage of First Nations communities with a licensed institutional care facility on-reserve | ||

| Persons reporting leaving their home communities to receive support for their disability | ||

| To what extend are these supports accessible to eligible individuals? | Percentage of cases where a resident on-reserve was assessed for services from the Assisted Living Program and received those services | |

| Number of recipients reporting "no service provided" or "alternative service provided" | ||

| Change in the ratio of institutional care clients to in-home care clients adjusted for demographic changes | ||

| To what extent do First Nation administrations and other program delivery agencies have the program management capacity and services delivery capacity to deliver services to individuals eligible under the Assisted Living Program? | Average score of risk-based compliance reviews | |

| Percentage of recipients who submit Data Collection Instruments, which are complete, error-free and on time. | ||

| Efficiency | Is the current level of funding for, and approach to, Assisted Living on-reserve sustainable in the long term? | |

| What approaches to Assisted Living programming could potentially achieve the best possible individual outcomes relative to the financial contribution? | ||

| To what extent is there overlap or complementarity between ISC's and Health Canada's social support program on-reserve? | ||

| Roles and Responsibilities | Are the current activities related to the provision of Assisted Living supports aligned with departmental strategic objectives and government priorities? | |

| Are the respective roles and responsibilities of ISC (Headquarters, regions), Health Canada, provincial governments, First Nation administrations, and other administrative agents effective, efficient and clear? | ||

| Program Design | Are the current program policies and regulations, including that of provincial comparability, appropriate and effective with respect to the desired outcomes? | |

| Does current program policy and design sufficiently facilitate the achievement ofprovincial comparability? | ||

| Are the stated outcomes appropriate and relevant? | ||

| Can ISC's current approach to Assisted Living be reasonably expected to achieve that stated outcomes? | ||

| Is ISC's approach to Assisted Living advancing reconciliation between the Government of Canada and Indigenous peoples? |