Evaluation of Clinical and Client Care Program 2012-2013 to 2016-2017

Final Report

August 2018

Format PDF (415 Ko, 51 pages)

Table of contents

List of Acronyms

| ACLS |

Advanced Cardiac Life Support |

|---|---|

| AHHRI |

Aboriginal Health Human Resource Initiative |

| BC |

British Columbia |

| CCC |

Clinical and Client Care Program |

| CPR |

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation |

| EKG |

Electrocardiogram |

| FTE |

Full-Time Equivalent |

| FNIHB |

First Nations and Inuit Health Branch |

| FNHA |

First Nations Health Authority |

| ITLS |

International Trauma Life Support |

| INAC |

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada |

| NRRS |

Nursing Recruitment and Retention Strategy |

| OT/SB/CB |

Overtime, standby, callback |

| PALS |

Pediatric Advanced Life Support |

| PEMH |

Percy E. Moore Hospital |

| R/I |

Remote and isolated communities |

| RNs |

Registered Nurses |

Executive Summary

This report presents the findings of the Clinical and Client Care (CCC) Program evaluation.

During the period under review, the CCC program was delivered and operated by the First Nations Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) of Health Canada. FNIHB programming was transferred to the newly created Department of Indigenous Services Canada in 2017 where the CCC program continues to be delivered.

The evaluation was a contracted project conducted on behalf of Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada's Office of Audit and Evaluation. At the time of publishing the report, the project was transferred to the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch of Indigenous Services Canada.

Evaluation Purpose and Scope

The purpose of the Clinical and Client Care evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the program during the period of April 2012 to March 2017, while also accounting for progress made since the 2015 Office of the Auditor General's assessment of the program.

The scope of the evaluation includes all program activities funded under the CCC program at the national and regional levels, including two federal hospitals in Manitoba. Out of scope are nursing stations in the north where clinical and client care services are provided by territorial governments, and in British Columbia where all responsibilities for federal health programs have been transferred to the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) through the British Columbia Tripartite Framework Agreement on First Nation Health Governance (2013).

The evaluation was undertaken by the Office of Audit and Evaluation at the Public Health Agency of Canada and has been conducted in accordance with requirements under the Financial Administration Act and the Treasury Board of Canada Policy on Results (2016).

Program Description

The CCC program is designed to provide essential primary care services to First Nations in remote and isolated communities (R/I) with limited or no provincial services readily available during regular operating hours and urgent/ emergent care after hours. Services are delivered by a collaborative health care team, predominantly nurse-led, and include:

- Emergency resuscitation and stabilization, emergency ambulatory care, and out-patient non-urgent services;

- Coordinated and integrated care and referral to appropriate provincial secondary and tertiary levels of care outside the community;

- Scheduled physician and other health professional visits; and,

- Hospital in-patient, ambulatory, and emergency service (Manitoba only).

The services are delivered in 74 nursing stations and five health centers with treatment located across five regions. Health Canada directly delivers services in 52 R/I First Nations communities located in four regions and provides funding through Contribution Agreements to 27 First Nations communities (including 12 in Saskatchewan, one in Alberta, one in Manitoba, four in Ontario, and nine in Quebec) to deliver services. The program is also responsible for two federal hospitals operating in Manitoba (Percy E. Moore Hospital and Norway House Hospital). In recent years (2015-16 - 2016-17), the two sites reported a combined average of approximately 8,400 visits annually, with Percy E. Moore accounting for the vast majority of those visits (7,900).

Evaluation Findings and Conclusions

Relevance

For First Nations living in remote and isolated communities serviced by the CCC program, there are no local alternative options for essential primary, urgent, and emergent health care services. As such, the provision of these services is consistent with the tenets of equal access outlined in the Canada Health Act (1984) and the need to improve Indigenous health outcomes, as articulated by the Indian Health Policy (1979).

The evaluation also found evidence of the program's alignment with overarching roles, responsibilities, and priorities of both the federal government and Health Canada's First Nations and Inuit Health Branch. However, the extent to which the CCC program is responsive to the priorities of the communities it serves is difficult to determine due to the nature of the program (e.g., largely reactive to emerging and urgent needs), limited community engagement in primary care, and little reliable data on utilization of services.

Irrespective of government mandate or priorities, the continued need for CCC programming is evident when considering the significantly poorer health outcomes experienced by First Nations compared to non-First Nations individuals. This is exacerbated by the complexity and high rates of chronic disease, as well as the significant presentation of First Nations individuals living with more than one health condition.

Performance

Overall communities are generally satisfied with the CCC services and hospital care they receive. The program has effectively improved clients' access to, and receipt of, quality care. By exploring interdisciplinary models of care, the program has facilitated greater access to a range of health care professionals, including nurse practitioners. However, challenges still vary across regions related to accessibility of physicians; and progress in hiring more nurse practitioners has not reached all communities. The program's expanded use of interdisciplinary models of care have allowed CCC sites to mitigate challenges raised by the 2015 Office of the Auditor General audit that found nurses were providing care that was beyond their legislated scope of practice.

The main challenges raised by key informants in regards to accessibility of CCC services were often outside the scope of the program (e.g., the condition and capacity of facilities, medical transportation, and road access), thus further highlighting a need to strengthen communication and collaboration across portfolio areas.

Key informants also identified limitations in equipment and diagnostic tools, staffing shortages, and limitations in the effective use of telehealth and other service based technologies as barriers to access.

While cost-effective alternatives/complementary approaches to delivering care have, to a certain extent, been resourced in communities, barriers still exist in fully maximizing their use. Currently, 93 percent of sites with CCC programming are equipped to offer telehealth services. Key informants were clear in saying the technology is available but challenges still exist concerning sufficient bandwidth, connectivity, staff's awareness and comfort level in operating the equipment, and a lack of clarity surrounding remuneration arrangements for physicians providing care through telehealth, which is under provincial/territorial responsibility. Ultimately, making full use of available technology could contribute to further efficiencies and potential cost savings in service delivery, while also providing greater opportunity to offer staff training at a distance.

In terms of ensuring staff are equipped to provide quality care, compliance with mandatory training has markedly improved. Staff completion rates increased from 27 percent in June 2015 to 60 percent in March 2017. However, they vary significantly across regions, affected by factors such as: timing and availability of course instructors; access to nurses to replace nursing staff requiring re-certification; as well as staff turnover. Furthermore, the evaluation found evidence that staff did not always feel properly prepared to work in remote and isolated First Nation communities due to limited awareness of the culture.

Although nurses do not intend to commit to a frontline CCC position for the length of their career, and there is a certain degree of understanding by the program that turnover is a natural state for the profession, there continues to be higher than expected turnover rates for the program. For example, in 2015-16 alone, the program hired 65 nurses, while facing 60 departures in that same year. While staffing turnover/shortages are a reality faced by health care settings in urban, rural, and remote locations, the evaluation recognizes the unique challenges present in R/I First Nation communities. The literature lists some of the following factors impacting recruitment of nurses for remote health care: limited number of nurses willing to relocate to an isolated community, as well as the need for specific personal suitability traits and a greater degree of adaptability to work with challenging cases, as well as limited resources and equipment. In the case of staff turnover, primary contributors identified through the evaluation included: work stress, availability of other job opportunities, the isolated location of the communities, and overall working conditions.

On the whole, since the implementation of the Nursing Recruitment and Retention Strategy in 2012-13, nurse vacancy rates have decreased from 40 percent to 16.2 percent, as of March 2017. While there is still reliance on agency nurses a cumulative cost savings of $18 million has been realized, far exceeding the intended cost savings of $2 million by 2016-17. This reduction in costs has been made possible due to fewer agency nurse hours, but as a result of increased agency rates, continues to be a cost driver irrespective of the fewer shifts filled by temporary staffing agencies. In addition, the program continues to have significant expenditures related to extended hours of operation (overtime, callback, and standby), but has since begun discussions to explore parameters around hours of work in an attempt to establish guidelines that are more consistent with client needs and the structure of nursing station/health centre work.

By providing access to clinical and client care services including urgent and emergent care after hours, the CCC program positively contributes to the health status of First Nation individuals in remote and isolated First Nations communities. However, achieving significant improvements in residents' health outcomes requires a multi-faceted approach where CCC is just one of many programs integrated into a service delivery landscape that captures the broad continuum of community-based programs for First Nations. At this point in time, there continues to be limited integration with provincial health services; as well as communication and collaboration between primary, home care, and other community-based programming such as mental wellness. In effect, the siloed program structure, as well as the multitude of programs and service providers, makes it challenging to ensure an integrated approach to both the planning and delivery of health care services.

Recommendations

The findings from this evaluation have led to the following four recommendations:

- Contribute to greater continuity of care by enhancing data collection, communication and sharing of information across health care providers in different jurisdictions.

To achieve greater integration of services and a stronger continuum of care, the degree of communication and collaboration among federal health programming for First Nations (e.g., Home and Community Care, Mental Wellness), and across health providers in different jurisdictions (including First Nations communities) should be strengthened. Areas for consideration include: enhanced data collection/reliability, and sharing of information to help better inform planning and decision making.

- Make more effective use of technology in the delivery of care and for training purposes.

Telehealth and other technologies available in most communities are currently not being used to their full potential. Action is required to address factors that can constrain the use of technology including connectivity issues (limited bandwidth), a lack of training and technical support, maintenance issues, and limited buy-in from service providers. In addition, there is opportunity to maximize the use of technology in delivering training for frontline CCC staff.

- Strengthen nurse recruitment and retention strategies, including efforts to address conditions that contribute to high rates of turnover amongst nurses.

There is a particular need to address conditions that contribute to nurse turnover. This involves addressing some of the root causes related to issues such as: scope of practice; security and safety; management and operation of nursing stations; and, overtime. Research, including data mining, a labour market analysis, and a survey of existing and former Health Canada nurses would enable the Department to better understand the drivers of turnover such that more effective retention strategies could be developed. - Ensure that formal cultural training is available and completed by all nurses employed in remote and isolated First Nations communities.

In order to provide responsive health services, it is important that CCC staff have a certain degree of cultural understanding. In recognition of the diversity of First Nations communities, it is also important that the training offered be tailored to reflect the diverse communities that each CCC site serves. As it stands, cultural training is provided as part of the orientation for new nurses, but the quality, structure, and consistency with which training is offered often varies. Ensuring that all nurses, both new and longer-term employees, have formal cultural training may positively contribute to the quality of care provided, and ease staff concerns related to their preparedness for providing health services in remote and isolated First Nations communities.

Management Response / Action Plan

Evaluation of the Clinical and Client Care Program—2012-2013 to 2016-2017

| Recommendations | Response | Action Plan | Deliverables | Expected Completion Date |

Accountability | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation as stated in the evaluation report | Identify whether program management agrees, agrees with conditions, or disagrees with the recommendation, and why | Identify what action(s) program management will take to address the recommendation | Identify key deliverables | Identify timeline for implementation of each deliverable | Identify Senior Management and Executive (Director General and Assistant Deputy Minister level) accountable for the implementation of each deliverable | Describe the human and/or financial resources required to complete recommendation, including the source of resources (additional vs. existing budget) |

| Contribute to greater continuity of care by enhancing data collection, communication and sharing of information across health care providers in different jurisdictions. | Management agrees with the recommendation. With a view to support health services devolution, FNIHB is committed to working with regions and its partners to better coordinate the sharing of information across various health care providers and jurisdictions to facilitate better continuity of care, while respecting privacy legislations on client information. This aligns with the following departmental result: Responsive primary care services are available to First Nations and Inuit. The CCC program will build upon its previous work accomplished in this area taking into consideration the locus of control. |

The CCC program in collaboration with the regions will produce a scan of the various quality improvement processes that are in collaboration with First Nations (e.g., discharge planning, interdisciplinary team meetings that span across the circle of care and trends in digital technology that support the continuity of care) to improve the continuity of care for clients between health care providers and jurisdictions involved in the circle of care. Challenges and opportunities will be identified and recommended next steps will be presented at the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch's Senior Management Committee to inform the Indigenous Services Canada health transformation agenda. The CCC program will also collaborate in utilising business intelligence tools, such as Synergy in Action, to better collect, analyse and report on nursing station information and other data (e.g., progress on accreditation). |

Report on regional engagement and quality improvement activities/ initiatives to improve the continuity of care. | December 2019 | Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations First Nations and Inuit Health Branch Regional Executive Officers Executive Director, Office of Primary Health Care, Population Health and Primary Care Directorate, FNIHB |

No additional resources required |

| Presentation to the Senior Management Committee on initiatives directed towards improving the continuity of care in First Nations communities. | March 2020 | |||||

| Updated Clinical and Client Care Dashboard/ Report Card | March 2019 | |||||

| Make more effective use of technology in the delivery of care and for training purposes. | Management agrees with this recommendation. FNIHB recognizes the importance of using technology in remote and isolated areas and is committed to leverage the use of technologies where possible considering current connectivity/ bandwidth issues and arrangements in place with health care providers. This aligns with the following departmental result: First Nations and Inuit health is supported by modern infrastructure and Indigenous governance. |

The CCC program in collaboration with the regions and academic institutions will assess the delivery mode for providing the onboarding and ongoing training/courses for nurses (e.g., face to face, online, group vs individual); potential expansion on the use of technology for providing training to nurses will be considered. | Scan of the current onboarding and ongoing courses (including delivery mode such as; in-class, face to face or online; group vs individual, videoconferencing, etc.) and its potential expansion to online delivery. | September 2019 | Executive Director, Office of Primary Health Care, Population Health and Primary Care Directorate, FNIHB Regional Executive Officers |

No additional resources required |

| The CCC program is also collaborating with the e-Health Program in order to implement new and effective remote presence health technologies (e.g., Doc in the Box, tele robotics, OTN Hub) that could enhance efficiencies and effectiveness of services in the communities. | The CCC program in collaboration with the eHealth will introduce remote presence technology initiatives in the regions where the infrastructure supports such technology. The duration of these projects will span from one to five years. | Interim Remote Presence Technology Pilot Project Report illustrating the challenges and opportunities of the effectiveness of remote presence technologies in the delivery of care | June 2020 | Executive Director, eHealth, CIAD FNIHB | Funding of $5M /5 years will be allocated to support this project through budget 2017 investments. | |

| Strengthen nurse recruitment and retention strategies, including efforts to address conditions that contribute to high rates of turnover amongst nurses. | Management agrees with this recommendation. The FNIHB Nurse Recruitment and Retention Strategy Steering committee will continue to oversee the development and the implementation of the Nursing Recruitment and Retention Strategy (NRRS) to address specific priorities and persistent issues. This recommendation contributes to the following departmental result: Responsive primary care services are available to First Nations and Inuit The development of comprehensive and ongoing education and clinical practice supports are essential to the overall integration and preparation of newly hired and current FNIHB nurses. |

Conduct a review of the NRRS marketing approach and products (e.g., photos used for advertisement, venues, etc.) will be conducted and changes will be made as appropriate. | Updated FNIHB NRRS marketing approach | March 2019 | Executive Director, Office of Primary Health Care, Population Health and Primary Care Directorate, FNIHB Regional Executive Officers |

Funding of $75K for photo shoot and other social media and print advertisements in 2018-19 Management Operational Plan pending approval. |

| In order to standardize the approach for onboarding at the regional level, a national policy on onboarding will be developed for nurses. | Nurse Onboarding Policy developed and approved | September 2018 | ||||

| To assess current changes in provincial legislation and regulations for nursing practice with a view to refine clinical practice support tools (e.g., registered nurse prescribers, updated list of essential services with point of care testing). This assessment would address the various distinct regional practices where primary care services are provided by FNIHB. | Report on regional nursing regulatory practice changes in order to refine clinical practice support tools | January 2020 | ||||

| To explore initiatives targeted at improving and influencing the pay process, where possible, in order to prevent pay irregularities for nurses. | Report on the development of a regional Pay Support Officer at the program level in Alberta. | January 2019 | ||||

| The FNIHB (CCC program) in collaboration with Professional Institute of the Public service of Canada has developed a memorandum of understanding to address significant safety and security issues in the work place. A work plan, including actions specific to safety and security in remote and isolated locations, such as an Indigenous Service Canada standard on security in remote and isolated work locations, will be developed to address the issues employees are facing regarding safety in the communities. | 2018-19 Workplan to address specific safety and security issues in remote and isolated locations | January 2019 | Funding of $100K to establish the new role. | |||

| The CCC program will also establish a role dedicated to nursing wellness for Northern Ontario and Manitoba to better support a healthy, safe and respectful workplace for nurses. | Wellness role in place to support a healthy, safe and respectful workplace for nurses. | March 2019 | ||||

| Ensure that formal cultural training is available and completed by all nurses employed in remote and isolated First Nations communities. | Management agrees with this recommendation. The Government of Canada is committed to advancing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada calls to action to provide cultural competency training for health care professionals. This recommendation contributes to the following departmental result: Responsive primary care services are available to First Nations and Inuit |

The CCC program in collaboration with the regions will include cultural competency courses and training as part of the standardized nurse onboarding for all FNIHB employed nurses. Regions to continue to move forward towards the identification of options for staff cultural competency training initiatives specific to the indigenous cultures in their regions. | To include specific cultural competency component to the standardized nurse onboarding policy. | September 2019 | Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch Regional Executive Officers |

|

| FNIHB is developing a cultural curriculum for all employees which will be a foundational element for cultural competency. | Regions to complement the nurse onboarding policy with additional regional training including customized cultural competency training. | National scan of regional adaptation and implementation of cultural competency training | October 2019 | Executive Director, Office of Primary Health Care, Population Health and Primary Care Directorate, FNIHB |

1. Evaluation Purpose

The purpose of the Clinical and Client Care (CCC) evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the program during the period of April 2012 to March 2017, while also accounting for progress made since the 2015 Office of the Auditor General's assessment of the program.

The evaluation was required in accordance with Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act, which stipulates that every five years departments conduct a review of the relevance and effectiveness of each ongoing program of grants and contributions. The Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Results (2016) defines such a review as a form of evaluation. The evaluation has been conducted to provide a credible and neutral assessment of the ongoing relevance and performance of the CCC program.

2. Program Description

2.1 Program Context

During the period under review, the CCC program was delivered and operated by the First Nations Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) of Health Canada. FNIHB programming was transferred to the newly created Department of Indigenous Services Canada in 2017 where the CCC program continues to be delivered.

The CCC program is one of two programs that supported Health Canada's First Nations and Inuit Health Branch's Primary Care sub-program. The program is designed to deliver primary care services to First Nations in remote and isolated communities (R/I) with limited or no provincial services readily available. Funding is administered through contribution agreements and direct departmental spending. The program was developed to meet the primary health care needs of R/I First Nations communities. Remote and isolated communities are defined as "those First Nation communities where transit time to provincial treatment facilities is over four hours by ground transportation. There are four types of R/I communities including Type I (Remote/Isolated Satellite) with no year-round access and intermittent air service; Type II (Isolated) with no year-round road access but regular air service; Type III (Semi-Isolated) communities located one to two hours (or more than 90 km) by road or water from emergency medical services; and Type IV (Non-Isolated Rural/Urban) communities located less than one hour (or less than 90 km) from emergency medical services."Footnote 1

2.2 Program Profile

CCC programming is designed to provide essential services during regular operating hours and urgent/emergent care after hours, seven days per weekFootnote 2. The services, which are delivered by a predominantly nurse-led, collaborative health care team, include:

- Emergency resuscitation, stabilization, and ambulatory care (referred to as emergent care); and out-patient non-urgent services;

- Coordinated and integrated care and referral to appropriate provincial secondary and tertiary levels of care outside the community;

- Scheduled physician and other health professional visits; and,

- Hospital in-patient, ambulatory, and emergency services (Manitoba only).

CCC services are delivered in 74 nursing stations and five health centers with treatment, located across five regions. The CCC health services are directly delivered by Health Canada in 52 R/I First Nations communities located in Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec. Health Canada also provides funding to 27 First Nations communities (including 12 in Saskatchewan, one in Alberta, one in Manitoba, four in Ontario, and nine in Quebec) to deliver these services.

| Regions | Alberta | Saskatchewan | Manitoba | Ontario | Quebec | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing Stations | 4 | 12 | 22 | 25 | 11 | 74 |

| Health Centers with treatment | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Regions | Alberta | Saskatchewan | Manitoba | Ontario | Quebec | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Canada Managed | 4 | - | 21 | 25 | 2 | 52 |

| First Nations Managed | 1 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 27 |

| Total All | 5 | 12 | 22 | 29 | 11 | 79 |

Note: Does not include federal hospitals (two) in Manitoba |

||||||

In addition, Health Canada is responsible for two federal hospitals located in Manitoba:

- Norway House Hospital is situated at the northern tip of Lake Winnipeg and linked to Winnipeg year-round by daily flights and an all-weather road. The hospital has seven in-patient beds and underwent renovations in 2011, which included the upgrade of 12 examination rooms, treatment and triage rooms. The hospital has a laboratory, x-ray, on-site pharmacist, and social services.

- Percy E. Moore Hospital (PEMH) is located 192 kilometres north of Winnipeg and easily accessible by highway. The hospital is a 16-bed, four-bassinet facility and has resident physicians, a full-time pharmacist, and social workers providing health-care services.

Service Providers

The CCC services are provided by qualified health care professionals who must have the necessary competencies and meet the regulatory and legislative requirements of the provinces in which they practice. They are assisted by unregulated health workers such as health care aides and community health representatives, rehabilitation aides, laboratory and X-ray technicians, pharmacy technicians and support personnel such as health receptionists. Nurses play a central role in the delivery of health services in R/I First Nation communities. In most R/I communities, essential treatment services are provided by nursing staff, including registered nurses, registered psychiatric nurses, and nurse practitioners, licensed or registered practical nurses supported by off-site medical practitioners and/or nurse practitioners. For residents in most of these communities, the CCC program is often the first point of contact with the healthcare system. In nursing stations or health centers with treatment, registered nurses consult, often at a distance, with other health care providers and services, including physicians, to provide a broad range of essential services. Telehealth is another service used to enhance access to additional services as required.

Governance

The CCC program is governed by FNIHB 's national office and regional offices, which are responsible for oversight of all FNIHB programs, including the CCC. The Senior Management Committee includes representation from FNIHB national and regional senior management, the Assembly of First Nations and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. The Committee discusses and determines objectives, plans and priorities, and informs operational and financial plans.

The FNIHB national office is responsible for policy development and program planning, including national program framework design, national project reporting and branch-level special studies, provision of advice and/or guidance on program delivery, and working with First Nations and Inuit partnersFootnote 3 to ensure effective program delivery.

Regional offices collaborate with Indigenous communities and organizations as well as Health Canada senior management to determine and review regional priorities in the context of national priorities and establish strategies to address regional needs. Regional offices play a lead role in the management of contribution agreements, which involves regional program performance monitoring, reporting, information roll-up, supporting communities with program delivery and working with First Nations partners at regional and local levels.

2.3 Program Narrative

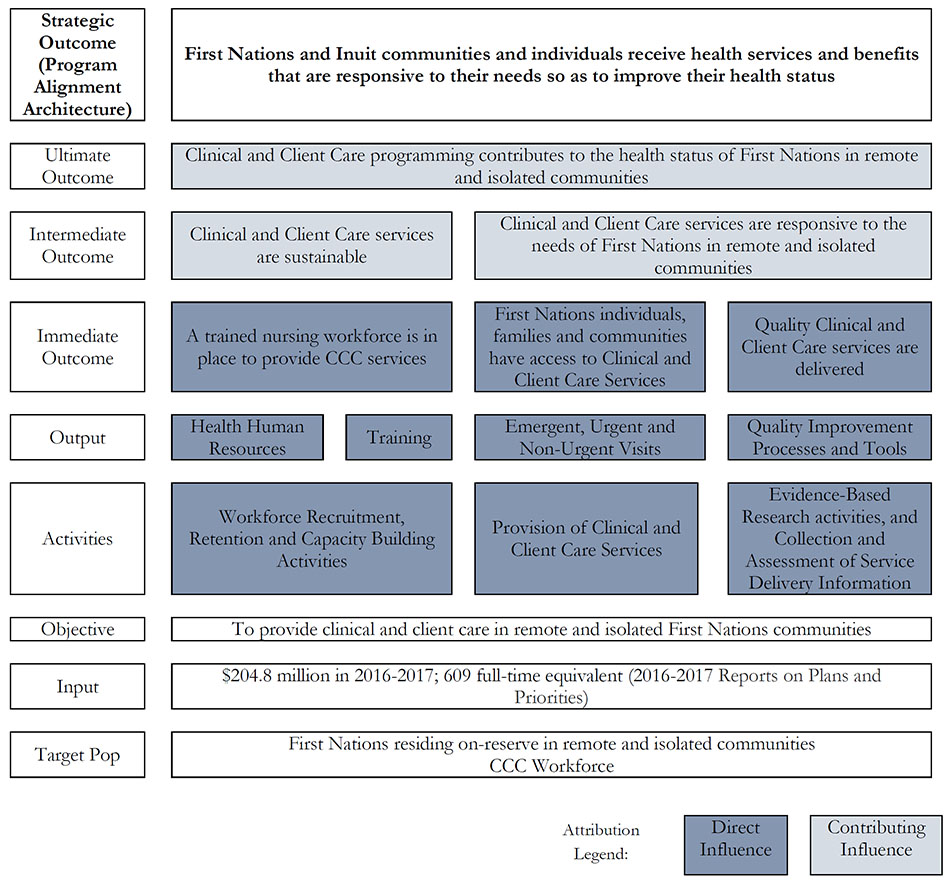

The primary objective of the CCC program is to provide access to clinical and client care services in R/I First Nations communities. In the logic model (2016) contained in Appendix 1, Program Activities are grouped under three categories: workforce recruitment, retention and capacity building activities; provision of clinical and client care services; and evidence-based research activities, and collection and assessment of service delivery information. Program outputs include: health human resources; training; emergent, urgent and non-urgent visits; and quality improvement processes and tools. The immediate outcomes, which are directly attributable to CCC outputs, include:

- First Nations individuals, families and communities have access to CCC Services, enabling needs to be addressed in the R/I communities. By making programming available locally, barriers to accessibility (e.g., transportation) are reduced and individuals can benefit from the services offered.

- A trained nursing workforce is in place to provide CCC services. Health Canada hires health care providers with the required education and experience and provides mandatory training to ensure nurses have the skills and abilities needed to work within the demanding clinical and client care environment of R/I communities.

- Quality CCC services are delivered. Clinical practice guidelines, processes, training and tools are developed to improve the quality of services provided to CCC clients and their families.

The CCC program's immediate outcomes contribute to achievement of intermediate and ultimate outcomes. For example, the provision of culturally relevant training, continuing education, and professional development contributes to a trained CCC workforce, which in turn contributes to the sustainability of the program and its ability to contribute to the health status of First Nations living in R/I communities in the long term. All outcomes are related to the Branch Strategic Outcome, which states that First Nations and Inuit communities and individuals receive health services that are responsive to their needs so as to improve their health status.

2.4 Program Alignment and Resources

The CCC fell under Health Canada's Sub-Program 3.1.3 First Nations and Inuit Primary Care, from which it receives transfer payment funding. Actual expenditures of the program in 2016-17 totalled $187 million, of which 37 percent was allocated through contribution agreements. The remaining 63 percent was expended directly by Health Canada for service delivery. The following table outlines the actual program expenditures over the period from 2012-13 to 2016-17.

| Expenditures | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salaries | $49.9 | $53.2 | $69.1 | $68.2 | $67.4 | $307.9 | 36% |

| Operations and Maintenance | $46.3 | $48.1 | $46.9 | $52.1 | $58.2 | $251.6 | 30% |

| Contributions | $55.1 | $58.9 | $68.0 | $64.9 | $65.2 | $312.0 | 37% |

| Revenue/Other | -$3.8 | -$3.3 | -$3.4 | -$3.7 | -3.6 | -17.8 | -2% |

| Total: Clinical and Client Care | $147.5 | $156.9 | $180.6 | $181.5 | $187.3 | $853.7 | 100% |

Source: Financial data provided by the Chief Financial Officer Branch, Health Canada |

|||||||

3. Evaluation Description

3.1 Evaluation Scope, Approach and Design

The evaluation was a contracted project conducted on behalf of Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada's Office of Audit and Evaluation. At the time of publishing the report, the project was transferred to the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch of Indigenous Services Canada.

The period covered by the evaluation includes activities from April 2012 to March 2017. The scope of the evaluation includes all program activities funded under the CCC program at the national and regional levels. Out of scope are nursing stations in the northern region provided by the territorial governments and the pacific region. In British Columbia, all responsibilities for federal health programs have been transferred to the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) through the British Columbia Tripartite Framework Agreement on First Nation Health Governance, signed in 2011. The British Columbia (BC) FNHA services were reviewed as part of the case studies to identify best practices and alternative delivery models that could be adapted by Health Canada.

The Treasury Board's Policy on Results (2016) guided the evaluation design and data collection methods such that the evaluation would meet the objectives and requirements of the policy. A non-experimental design was used. As this program focuses on First Nations communities, the Assembly of First Nations was consulted during the development of the scoping deck and evaluation methodology, and provided with an opportunity to review and comment on the evaluation instruments, the preliminary findings, and the evaluation report. For more detailed methodology, see Appendix 2.

The evaluation employed multiple lines of evidence, including:

- A document, file and data review consisting of internal documents, programs evaluations, program reports, regional reports and inventories, and financial data;

- A literature review focused on peer-reviewed literature related to best practices in delivery of services in remote and isolated communities;

- Surveys with 118 health professionals across five regions;

- Interviews with 46 key informants, including FNIHB national and regional program staff, other Health Canada program representatives, provincial governments, regional health authorities, health associations, and other stakeholders (out of 13 health directors, seven were from transferred communities);

- Six community case studies involving visits to five communities and a federal hospital in Manitoba. Including the hospital, a total of 73 interviews were conducted, of which 33 representatives were from two communities where health services were managed by the First Nation, 25 representatives were from three communities with health services managed by Health Canada, and 15 representatives from the hospital. The evaluators toured the facilities and reviewed available health plans and other documents; and

- A comparative analysis case study focused on the BC FNHA to identify best practices. The case study involved a review of publicly available documents on the design and delivery of the CCC program in British Columbia, as well as interviews with six representatives of BC FNHA and one representative of British Columbia Ministry of Health.

In total, at least 57 representatives from First Nations managed sites participated in the evaluation via key informant interviews (seven), surveys (17) and case studies, which included interviews (33). The use of multiple lines of evidence and triangulation increases the reliability and validity of the evaluation findings and conclusions. The quantifiers used to report findings from key informant interviews are as follows:

- Most means over 80 percent of those responding to the question;

- Majority means between 50 percent and 80 percent of those responding to the question;

- Some means between 25 percent and 50 percent of those responding to the question; and,

- A few means less than 25 percent of those responding to the questions or two to four respondents.

3.2 Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Most evaluations face constraints that may have implications for the validity and reliability of evaluation findings and conclusions. Table 3 outlines the limitations encountered during implementation of the methods selected for this evaluation. Also noted are the mitigation strategies put in place to ensure that the evaluation findings can be used with confidence to guide program planning and decision making.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Some data on program outputs and outcomes has only been collected since 2015. | Limited analysis for some outcomes with respect to the progress made. | Other proxy indicators were used to comment on the progress made such as perceptions of key informants, and health professionals. |

| Variations across the regions/communities in program delivery. | Limitations in applying evaluation findings to all regions/communities. | The evaluation emphasizes areas where differences across regions or communities were found. Case studies highlight such differences. |

| Limited availability of data from First Nations operated sites (transferred communities). | Challenges in conducting a comparative analysis of delivery of services in Health Canada and First Nation managed sites. | Analyses are based on primary data collected through interviews with nearly 40 health professionals and managers working in transferred communities, and interviews with 11 community members. |

| Key informants had varying levels of knowledge of the services. They responded selectively to the questions related to their area of expertise or knowledge. | The number of key informants responding varies across questions. | Qualitative analysis of interview data was conducted for each question/topic according to key informants' role and knowledge of a particular area. |

| Detailed financial data was not available for different program components by region. Discrepancies in costs reporting. | Unable to provide more detailed analysis of efficiency and economy of the program and effectiveness of cost reduction strategies. | Higher level analyses were done related to costs associated with Health Canada vs. agency nurses. |

4. Findings

4.1 Relevance: Issue #1 – Continued Need for the Program

There is a continued need for clinical and client care services in R/I First Nations communities, which is projected to increase given the population growth, an aging demographic, continuing disparities in health outcomes, the complexity and co-morbidity of disease, and the increasing need to provide care related to chronic disease management, mental health and specialized care.

The First Nations Regional Health Survey (2008-10) reported that First Nations in Canada experience higher rates of chronic health conditions and multiple conditions than non-First Nations, including diabetes, high blood pressure, stomach and intestinal problems, and high levels of psychological distress. About two-thirds (63 percent) of First Nations adults indicated having at least one chronic health condition, with just under 40 percent reporting having two or more conditions. In comparison, one in five Canadian adults lives with one of the following chronic diseases: cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, or diabetes, according to a recent study by Health Canada on prevalence of chronic diseases among CanadiansFootnote 4. Furthermore, 51 percent of all First Nations adults (with a greater proportion of females than males) report either moderate or high levels of psychological distress, as compared to 34 percent of the general Canadian population.

The need is projected to increase. According to newly released data by Statistics Canada on 2016 Census Data, the First Nations population grew by 39.3 percent from 2006. This is about four times the growth rate of the non-Indigenous population over the same periodFootnote 5. Close to half (44.2 percent) of First Nations people with registered or treaty Indian status, lived on-reserve in 2016, registering a growth of 12.8 percent for on-reserve population. Although the First Nations population is young, many First Nations communities have a growing aging population, which will further increase demand for services. According to Statistics Canada (2017) projections, populations 65 years of age and older could more than double by 2036.Footnote 6

The CCC services complement other health programs delivered in remote and isolated First Nations communities, although limited collaboration and information sharing across programs in some communities has resulted in gaps and areas of overlap.

The CCC program is the only source of primary clinical care services in the R/I communities. It is also a front-line service, on the continuum of careFootnote 7, that is highly dependent on number of other federal, provincial and community health support programs. For example, the program works closely with provincial services such as those responsible for medical air evacuation and provincial hospital programs. With respect to Health Canada services, the program is closely linked with the Home and Community Care Program, e-Health Infrastructure Program and the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program, which provide support for related services such as medical transportation, emergency services and other specialized services.

The program is largely perceived as complementing other programs available in the communities in providing continuity of care. However, some key informants, involved in the management and delivery of the CCC program (health directors and FNIHB regions), noted difficulties with respect to coordinating services across various programs given the number of health programs, delivery organizations and employers involved, and limited communication and collaboration (e.g., siloed program structures). Case studies identified that a lack of coordination and information sharing between the CCC and Home and Community Care Program in some communities has created gaps and duplication of services in areas such as chronic disease management, prenatal services, and healthy living. For example, nurses in one community visited reported that they have no way of knowing what information has been given to their patients or whether, in fact, the patients have been visited by a home care worker.

4.2 Relevance: Issue #2 – Alignment with Government and First Nation Priorities

The Government of Canada has demonstrated the priority it places on the delivery of clinical and client care in the communities by making significant additional investments to stabilize operations, enhance models of care, and support the construction, renovation and repair of nursing stations and residences.

Since the last evaluation, the federal government has increased the financial allocation to the program, confirming its on-going commitment to improving health care and health outcomes of First Nations in Canada. Budget 2013 included $211 million in supplemental funding over five years to stabilize the CCC program and ensure that essential primary services are available in First Nation communities to address immediate health needs. The budget in 2014-15 outlined initiatives to further enhance models of primary health care with the goal of re-orienting current practices to support modern, sustainable, high-quality health care in R/I First Nations communities. Budget 2016 included a significant investment in health infrastructure through the Health Care Facilities Program; $270 million over five years will be used, in part, to support the construction, renovation and repair of nursing stations, residences for health care workers, and health offices that provide health services on-reserve. The Health Canada departmental plan (2017-18) reports that improving health services and developing innovative partnerships to close the Indigenous health gap remains a top priority for Canada. Budget 2017 proposes to invest $828.2 million over five years to improve the health outcomes of First Nations and Inuit, of which $72.1 million has been allocated to Primary Care.

The program aligns directly with broad strategic priorities identified in collaboration with First Nations. The extent to which the program is well aligned with local First Nations' priorities varies across communities, and is related to factors such as level of community engagement, ability to proactively identify issues, and flexibility of resources.

The First Nations and Inuit Health Branch Strategic Plan: A Shared Path to Improved Health (2012) outlined health priorities identified in collaboration with First Nations representatives, other governments and Health Canada. The intended outcomes of the CCC program align directly with the goal of providing high quality health services across the continuum of care for individuals, families and communities.

Over one-half of the key informants working with the communities with Health Canada- managed CCC services, agreed that the program is aligned with the priorities of First Nations communities. Key informants highlighted Health Canada's efforts to identify priorities and structure services accordingly, in collaboration with First Nations communities (e.g., the development of health care planning guides and toolkits to facilitate planning). Nearly one third of key informants indicated a lack of alignment with local priorities, and listed the following barriers: difficulties in engaging the community in a meaningful way and limited flexibility with respect to allocating resources in response to emerging issues and priorities. They also noted that the immediate pressures of having to address emergency and clinical care needs often result in other priorities being overlooked, such as chronic care management or mental health care. FNIHB representatives noted that planning is challenging given the nature of urgent and emergent health services (i.e., the program is designed to respond to immediate needs), but added that delivery of services could still be better aligned with the local community needs (e.g., by adjusting hours of operation, allowing for greater flexibility in the allocation of resources and models of care, etc.)

Key informant data indicates that staff perceive better alignment with local First Nations priorities in First Nations- managed CCC sites. Nearly all representatives working in First Nations managed CCC sites, compared to approximately half of staff surveyed in Health Canada managed sites agreed that the program is aligned with the local priorities of First Nations communities. Some transferred communities tend to be more effective in engaging the community. Health directors from transferred communities reported using meetings, surveys and other ongoing engagement to

identify priorities or concerns, which were then communicated to health boards or health managers who then work together towards addressing the issues raised. For example, under their funding agreements, transferred communities can have greater flexibility to quickly and effectively respond to the emerging priorities (e.g., by hiring a mental health nurse).

4.3 Relevance: Issue #3 – Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The program is aligned with federal government and departmental roles and responsibilities.

The federal government shares responsibility for improving the health of Indigenous people with provincial and territorial partners and Indigenous organizations. Federal government funding for CCC services is aligned with provisions found in the Canada Health Act (1984), the Indian Health Policy (1979), and other Health Canada policies. The 1979 Indian Health Policy recognizes the special relationship between the federal government and Indigenous people, the interrelated nature of health system, and the role of the federal government in "providing public health activities on reserves, health promotion and detection and mitigation of hazards to health in the environment"Footnote 8.

The CCC policies and practices are generally aligned with provincial health legislation and regulations. FNIHB has taken steps to ensure that nurses are working within their scope of practice in each jurisdiction; however, concerns remain in some communities.

Provincial legislation governs nursing practice in each region. Over half of key informants involved in the delivery of the CCC (e.g., regional FNIHB representatives, health directors and nurse managers) reported that CCC policies and practices are consistent with provincial legislation (e.g., legislation regarding maintenance and inspection of diagnostic tools, laboratory licenses, transportation of dangerous goods, etc.).

Nursing scope of practice is regulated by the provincial regulatory bodies. Significant concerns about nurses working outside of their regulated scope were raised in the previous CCC Evaluation (2013) and Auditor General Report (2015). Two-thirds of key informants noted that necessary steps were taken to address these concerns, through actions such as introducing interdisciplinary teams, increasing access to nurse practitionersFootnote 9, and adding full-time paramedics or full-time physicians (in transferred communities) to broaden the skill sets within the health teams working at the nursing stations. In Saskatchewan, the Additional Authorized Practice certification allows Registered Nurses (RNs) to practice with an expanded scope (e.g., RNs can prescribe and dispense certain controlled drugs and substances, order tests, prescribe vaccines, and perform minor procedures).

Although progress has been made, there are still some concerns related to ensuring that nurses practice within their regulated scope. About one-third of key informants, provincial and regional FNIHB representatives noted that nurses may still work outside their scope of practice in areas where access to other health professionals is limited. When asked about the major factors that contribute to a high rate of nurse turnover in their communities, 28 percent of the nurses surveyed identified concerns about the scope of practice.

4.4 Performance: Issue #4 – Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

4.4.1 To what extent have the immediate outcomes been achieved?

Immediate Outcome #1: First Nations individuals, families and communities have access to Clinical and Client Care Services (including federal hospitals).

Through nursing stations and hospitals, the CCC provides all R/I communities with access to essential clinical and client care services during regular weekday hours as well as access to urgent services after hours. Nearly 70,500 residents in communities with Health Canada- managed services made approximately 370,000 CCC visits in 2015-16 (over a third of which were made after hours) while approximately 8,400 visits were made to the two federal hospitals in Manitoba. In 19 First Nations-managed communities that reported data in 2014-15Footnote 10, close to 130,000 urgent and non-urgent visits were made.

Most health professionals surveyed agreed that First Nations individuals, families and communities have access to the clinical and client care they need in the communities. According to nursing inventories conducted in 2016, all R/I communities have access to essential clinical and client care during regular weekday hours (8:30 to 17:00 Monday to Friday), and urgent services after hours delivered by health care professionals on-call. The regular hours of operation may vary slightly across the nursing stations. Some stations close occasionally, providing emergency only services during staff rotation or on days when they are short staffed.

Of the 368,374 visits reported to Health Canada-managed CCC services in nursing stations and health centres with treatment across the four regions in 2015-16Footnote 11, 63 percent were made during regular hours and 37 percent occurred after-hours. While after-hour services are provided to ensure that R/I communities have access to urgent care, program utilization data indicates that only 15 percent of after hour visits were urgent (urgency of after-hour services varied across the regions, from 95 percent in Alberta to 33 percent in Ontario and 10 percent in both Quebec and ManitobaFootnote 12).

According to data from approximately 19 communities with First Nations-managed CCC services, the severity of cases seen in 2013-14 compared to 2014-15 has decreased. In 2013-14, one-third of the 156,000 visits accessed urgent care services, compared to less than one-fifth of the 130,000 visits in 2014-15 qualifying as urgent care.Footnote 13

Visitation data for the two federal hospitals indicate that there were about 7,900 visits annually to the PEMH over the past two years (2015-16 and 2016-17), while the Norway House Hospital has admitted an average of approximately 500 patients annually providing for an occupancy rate of about 50 percentFootnote 14. Non-urgent care accounts for over 60 percent of the visits to PEMH, with the demand attributed, by hospital representatives, largely to a lack of physicians in surrounding health clinics and rural hospitals (e.g., diversion from surrounding communities, clients prefer to access a physician at the hospital due to waiting times at the clinic). According to the hospital representatives, wait times at the hospitals vary depending on the level of acuity of conditions patients are presenting with, which are currently considered to be reasonable. In a survey, conducted by PEMH in February 2017, 42 percent of 49 emergency room patients indicated that their condition was always or usually addressed by a physician within one hour of their presentation to the Emergency Room, 34 percent said sometimes, and 16 percent said never. The average wait time for the Norway House Hospital from arrival at the Emergency Department to admission was 3.3 hours in 2015-16, which is skewed by the large numbers of non-urgent cases. A study of Emergency Room wait times in Winnipeg hospitals shows that emergency department wait times for a small number of patients (10 percent of non-urgent visits) are long (at least 4.7 hours), while the more urgent cases, experience wait times of approximately 42 minutes.Footnote 15

Key informants argued that R/I First Nations communities require greater access to clinical and client services than other similarly located communities because of the unique challenges they face.At the present time, access to RNs in some First Nations communities is higher than similar provincially-served communities, while access to timely physician and specialized care, particularly mental health professionals, varies across, and is limited in most communities.

In response to questions about whether R/I First Nations communities have access to services comparable to those in other similar communities, most key informants argued that there are no other similar communities. Communities served by the CCC program are unique in their challenges, particularly with respect to the degree of geographic isolation and accompanying transportation issues (65 percent of health professionals surveyed identified transportation issues as constraining access to services)Footnote 16, the model of care (nurse vs. physician-driven), access to diagnostic tools (e.g., point of care), the involvement of multiple levels of government in the delivery of services (e.g., the federal government, provincial government, and the band), the social determinants of health, infrastructure, and historical circumstances. Some key informants argued that any efforts to assess comparability should focus on equality of outcomes rather than achieving comparability of resources with the provincial systems. Given differences in the challenges faced by R/I First Nations communities, it was argued that equality of resources will not result in equality of outcomes.

A comparability of access study conducted by Health Canada using a sample of three communities meeting similar criteria, across three regions, concluded that access to services in First Nations remote communities was comparable, on most measures, to those provided in provincial rural communities. The study found that the nurse-to-population rate was generally higher in Health Canada facilities. However, the physician-to-population rate and visiting physician hours were lower in First Nations communities.Footnote 17 Access to physicians varies depending on the needs and remoteness of the communities, and is negotiated with provincial partners. Most health professionals surveyed as part of the evaluation identified long waiting times to access other health professionals or specialists (82 percent) or physicians (65 percent) as factors constraining access to care in the communities. In one of the communities assessed as part of the Quality Improvement Onsite Assessment, there was a two-month wait time to see a physician in the community. Nearly all community members and health professionals, interviewed as part of case studies, expressed concerns regarding access to physicians and other health specialists, particularly mental health professionals. Most key informants, including nearly all health directors interviewed, emphasized the challenges with respect to accessing mental health professionals and provincial mental health services, including difficulties scheduling appointments. Similar concerns were noted in regional 'Key Issues and Deficiency' documents (2016), which highlight challenges in accessing the resources needed to address acute mental health care issues (e.g., grief, acute anxiety, domestic violence, suicidal ideation with no plan, substance abuse).

While the Health Canada comparability of access study found that the nurse-to-population rate was higher in the communities where CCC programming is offered, the majority of key informants indicated that there is still a nursing shortage given the strong demand for services. Close to two-thirds of the health professionals surveyed identified nursing shortages as a major factor constraining access to services. This was particularly highlighted by health professionals from Ontario, where about 80 percent of respondents reported nursing shortages. A few health directors noted that access to the CCC services is not equal in all communities, indicating significant differences with respect to workloads and access to provincial care.

Immediate Outcome #2: A trained nursing workforce is in place to provide CCC services.

Measures taken by Health Canada have improved compliance with mandatory training for nurses. Barriers to achieving higher and more consistent compliance with mandatory training include: the rate of nurse turnover, availability of nurses to backfill for those requiring re-certification, costs of travel, training and replacements, and accessibility of the training courses.

Health Canada has taken multiple steps over the past few years to set out the guidelines and improve training compliance among Health Canada employed nurses. The updated national policy on Mandatory Training (revised 2015) outlines the roles and responsibilities for Health Canada employed nurses in obtaining and maintaining certifications in the following five mandatory courses: Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), International Trauma Life Support (ITLS), Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), Controlled Substances, and Immunization. Recertification is required every two (PALS, ACLS) to three years for mandatory training courses.

Most key informants noted that the national training policy (which includes responsibilities for monitoring compliance, and increased resources) has helped to improve compliance rates. As of March 2017, 60 percent of the 337 Health Canada nurses, across four regions, were fully compliant across all of the mandatory training. This is up from 46 percent in March 2016 and 27 percent in June 2015. Differences in the level of compliance across regions and type of training are indicated in Table 4. To achieve full compliance, regions must ensure that nurses have up-to-date certification in all five mandatory training courses. As illustrated in the following table, failing to meet requirements in one course (as was recently the case for PALS recertification in Quebec), would result in none of the nurses being in full compliance with the mandatory training. Consequently, this criteria negatively impacts overall compliance rates.

| Region | ACLS | ITLS | PALS | Controlled Substances |

Immunization | Full Compliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta (30 Nurses) |

80% (24/30) |

80% (24/30) |

73% (22/30) |

80% (24/30) |

83% (25/30) |

53% (16/30) |

| Manitoba (174 Nurses) |

80% (139/174) |

75% (130/174) |

79% (138/174) |

74% (129/174) |

80% (139/174) |

43% (75/174) |

| Ontario (125 Nurses) |

94% (118/125) |

92% (115/125) |

90% (112/125) |

97% (121/125) |

95% (119/125) |

90% (112/125) |

| Quebec (8 Nurses) |

50% (4/8) |

38% (3/8) |

0% (0/8) |

63% (5/8) |

50% (4/8) |

0% (0/8) |

| Total (n=337) | 85% | 81% | 81% | 83% | 85% | 60% |

According to the document review and key informants, fluctuations in mandatory training compliance over time and across regions is a function of turnover (e.g., new nurses must obtain the mandatory certifications) and the availability of relief nurses to cover for existing nurses requiring recertification. At least three mandatory training courses (ACLS, ITLS, PALS) are delivered in the classroom, which requires nurses to travel out of the community and relief staff to be scheduled to provide replacement. The program estimates that a maximum of 40 hours per year is required for training for both full-time and part-time nurses. To put that in perspective, at this level and based on the number of Health Canada nurses employed as of March 31, 2017 (n=337), approximately 1,800 days each year would have to be filled by relief nurses to achieve 100 percent compliance.

Most regional FNIHB representatives, as well as some health directors, noted that insufficient resources are available to cover the costs of replacement, training and travel expenses. Accessibility of the mandatory training courses can also be challenging. About half of surveyed health professionals noted that the training is difficult to access. Depending on the region, the courses may be offered only once a month, on weekends, or when enough nurses have signed up for the course to be scheduled. Nurses strongly prefer not to be taking training during their scheduled time off. Some frustrations were expressed by Health Canada nurses during community visits regarding having to search for, schedule and pay for the training themselves, with some reporting that they received reimbursement only months after it had been completed.

To address some of these issues and reduce reliance on traveling for training, about half of key informants suggested that Health Canada should work more closely with the academic and other institutions to implement a combination of the following: make some parts of the mandatory training available online, increase the use of telehealth for trainingFootnote 18, and provide on-site instruction for aspects of training that require hands on experience. In British Columbia, FNHA representatives highlighted e-Health initiatives as a promising practice to deliver training. These initiatives have provided two-way live video conferencing support for clinical and health-related education to about 150 First Nations communities across British Columbia.

An onboarding and orientation process for new nurses is in place. However, it is unevenly implemented.

In addition to national mandatory training, each region provides a number of essential training activities for nurses, which are in line with the provincial requirements, such as Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR), Transportation of Dangerous Goods, Nurse Safety Awareness Training, Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System, and other relevant skills development training. The regions are also responsible for providing orientation to new nurses. To deliver training, regions use various strategies such as telehealth, train-the-trainer for immunization courses or CPR, and having paramedics provide training on-site.

A few key informants noted that the National Onboarding Checklist (2017) was developed to standardize the onboarding process, provide information about various roles, responsibilities, and the clients, and offer links to additional resources. As part of the onboarding process, during their first few weeks, new nurses receive orientation and mentoring at the regional office and in the community. Over half of nurses surveyed agreed that new nurses are provided with the orientation and mentoring support they need. However, close to a third disagreed that the orientation was adequate. The case studies indicate that there can be significant differences across communities in terms of the quality and duration of the orientation as well as the emphasis placed on mentoring. For example, one of the visited communities offered a well-structured on-site orientation for the first two weeks, delivered by a nurse practitioner. The orientation included an overview of the nursing station policies, organizational structure and management structure as well as an introduction to the community in terms of culture, language and political structure. In other communities, there was less emphasis placed on formal orientation ("nurses learn by doing"), particularly where there has been turnover at the management level (e.g., nurse manager or nurse-in-charge). Most health directors noted that there is a need for more comprehensive onboarding, orientation and mentoring process for new employees to adequately prepare them for remote practice environment (e.g., longer orientation with more hands-on training with remote practice skills and environment, standardization of process, understanding of 'how things work').

Gaps were identified related to various elements of the mandatory training courses and formal cultural sensitivity training.

In R/I First Nations communities, nurses face emergency situations that require training beyond what basic nursing education programs provide. The Department specifies mandatory training for these nurses to complete, including courses in areas such as immunization, cardiac life support, and the handling of controlled substances in First Nations health facilities. Specified mandatory and essential training requirements, along with the clinical practice guidelines, aim to prepare the nurse to work in this challenging environment, and enable them to practice to the full extent of their education, training, and competencies, and foster inter-professional collaboration.

The most common challenge related to training, reported by 54 percent of health professionals, is that training does not reflect the full range of competencies needed to work in R/I First Nations communities. Various gaps and issues were identified in the health professionals survey, case studies, and document review, which can be divided into three categories:

- The limited relevance of some parts of training courses to providing essential health services in R/I communities. For example, ACLS/PALS training includes topics that are based on having access to a physician when the situation requires interventions outside the nurses' legislated scope of practice, and the ITLS training is viewed to be targeted towards paramedics rather than nurses. Over 10 percent of nurses surveyed reported that the training they received is not fully aligned with community needs, such as mental health and addiction-related training, prenatal counselling, nutrition, chronic disease management, case management, and the over-prescribing of antibiotics. CCC internal program documents (2016) highlighted that nurses are not well trained in Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale as the standard classification for triaging patients.

- Limited access to management training on operational, management and human resources issues for nurses-in-charge or nurse managers (highlighted in the case studies as a gap by the nurses-in-charge). Given the workload and other training requirements, such training to the extent that it is available, is not a priority for nurses in management positions. Over half of health professionals surveyed identified a lack of time as a barrier to accessing needed training.

- Lack of training related to information collection, data management and use of technology. For example, all nurse managers spoke about the importance of systematic and consistent information records in patient charts for effective case management. The level of technology utilization (e.g., telehealth equipment) is dependent upon the skills of the staff and can be impacted by turnover, highlighting the need for ongoing technical training.Footnote 19

The need for more formal cultural sensitivity training was identified by most key informants including about half of health directors, and nearly all health staff participating in interviews as part of the case studies. A few regional FNIHB representatives called it the most significant gap in training. About half of nurses interviewed, most of whom had been employed by Health Canada for less than two years, noted that, when hired, they received some cultural sensitivity training; however, the overall volume of material covered as part of their orientation makes it hard for them to retain that part of the training.

The review of practices in British Columbia shows that FNHA implements a formal mentorship program for new nurses, including a cultural safety component. The regional FNHA representatives interviewed emphasized their commitment to cultural training for all health providers, and other initiatives that integrate culturally safe practices in health service to meet the needs of First Nations. To improve delivery of cultural training, the FNHA has established mandatory cultural competency training for all FNHA employees (online module); integrated First Nations cultural safety and humility within health services by signing the first-ever Cultural Safety and Humility Declaration between British Columbia's health authorities and the Deputy Minister of Health for each regional health authority in British Columbia; developed and delivers a webinar series on cultural sensitivity and humility (delivered by the Chief Executive Officer); and created an evaluation framework to measuring the impact of cultural safety and humility interventionsFootnote 20.

Immediate Outcome #3: Quality Clinical and Client Care services are delivered (includes hospitals)Footnote 21

Quality of care is a function of a variety of factors, including the presence and use of relevant policies and standards, the stability of the workforce and diagnostic capabilities. Relevant policies and standards are in place and used regularly, contributing to the quality of care. However, some gaps in policies and issues were identified with respect to staff turnover and diagnostic services.

Most program representatives (FNIHB and health directors) noted that relevant standards and policies are in place to ensure that the health services are of high quality. The policies are most commonly developed by the national office and then adjusted by regions to ensure alignment with provincial standards. Policies and tools that have been created and updated to ensure high-quality services include a National Education Policy, FNIHB Health Facilities Safety and Security Policy updates (March 2016), Infrastructure-Related Health and Safety Risks, and Patient Safety Incident Management. Key informants also reported that new quality improvement processes and tools have been developed to ensure quality services, such as the 'Essential Service templates' which are used as a tool for ensuring the minimum resources required by nursing stations are in place. In September 2016, FNIHB piloted a quality improvement on-site assessment process in two R/I nursing stations to inform the nurse-in-charge and nurse managers of gaps so that they can develop a plan to address the issues.

Most nurses strongly or somewhat agreed that nurses make good use of relevant policies and standards in their practice. The Clinical Practice Guidelines were identified as the most commonly used policy document (91 percent of health professionals surveyed reported using it daily). Other policies commonly used by health professionals surveyed include: Nursing Station Formulary and Drug Classification System (75 percent use it on regular basis); FNIHB Policy and Procedures on Controlled Substances (58 percent); and to, a lesser extent, the Diabetes Canada Practice Guidelines (39 percent). In addition, nurses reported frequently using anti-infective guidelines, hypertension guidelines, public health and immunization documents, and various specialized guidelines (e.g., cervical screening, pediatric guidelines, etc.).

Some gaps in policies were identified, of which the most common were gaps and outdated standards in the Clinical Practice Guidelines (identified by 71 percent of nurses) in areas such as mental health, Sexually Transmitted Blood Borne Infections, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, antibiotics use, diabetes care, etc. About one-third of the health professionals interviewed during case studies, noted that they look to provincial standards for best practices with respect to some of the gaps observed. Most participants in case studies also identified gaps or issues related to procedures or protocols (e.g., governing issues such as communication and information sharing between programs, operating policies, procedures or handling complaints).

Staff turnover negatively impacts quality of careFootnote 22. The community members who were interviewed as part of the case studies most commonly defined quality of care in terms of the relationship and trust they have developed with their health care providers. In fact, the literature shows that patient perception of health care quality and treatment outcomes are highly correlated with the level of trust that has been established, and effective communication, as well as perception of professional competency.Footnote 23 In one community, health staff spoke of a physician who has been able to build a strong relationship with community members over time, which resulted in increased visits, decreased cancellation of scheduled visits, and more individuals (particularly older men) opening up about their mental health Similarly, health directors identified a stable nursing staff as a key determinant of quality of care, which enables nurses to become more aware of local health concerns, familiarize themselves with the community, and connect with clients over time. A literature review conducted in Ontario (2017) found that four principles (respect, trust, self-determination, and commitment) underline successful approaches and meaningful ways of engagement with First Nations communities. Commitment is seen as part of the engagement process, which takes time and community presence among other thingsFootnote 24.